NEW LONDON VILLAGES Creating Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

City Villages: More Homes, Better Communities, IPPR

CITY VILLAGES MORE HOMES, BETTER COMMUNITIES March 2015 © IPPR 2015 Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies Institute for Public Policy Research ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive thinktank. We are an independent charitable organisation with more than 40 staff members, paid interns and visiting fellows. Our main office is in London, with IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated thinktank for the North of England, operating out of offices in Newcastle and Manchester. The purpose of our work is to conduct and publish the results of research into and promote public education in the economic, social and political sciences, and in science and technology, including the effect of moral, social, political and scientific factors on public policy and on the living standards of all sections of the community. IPPR 4th Floor 14 Buckingham Street London WC2N 6DF T: +44 (0)20 7470 6100 E: [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This book was first published in March 2015. © 2015 The contents and opinions expressed in this collection are those of the authors only. CITY VILLAGES More homes, better communities Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies March 2015 ABOUT THE EDITORS Andrew Adonis is chair of trustees of IPPR and a former Labour cabinet minister. Bill Davies is a research fellow at IPPR North. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editors would like to thank Peabody for generously supporting the project, with particular thanks to Stephen Howlett, who is also a contributor. The editors would also like to thank the Oak Foundation for their generous and long-standing support for IPPR’s programme of housing work. -

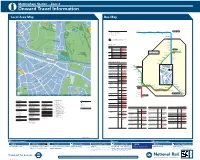

Local Area Map Bus Map

Mottingham Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 58 23 T 44 N E Eltham 28 C S E R 1 C Royalaal BlackheathBl F F U C 45 E D 32 N O A GolfG Course R S O K R O L S B I G L A 51 N 176 R O D A T D D H O A Elthamam 14 28 R E O N S V A L I H S T PalacPPalaceaala 38 A ROA 96 126 226 Eltham Palace Gardens OURT C M B&Q 189 I KINGSGROUND D Royal Blackheath D Golf Club Key North Greenwich SainsburyÕs at Woolwich Woolwich Town Centre 281 L 97 WOOLWICH 2 for Woolwich Arsenal E Ø— Connections with London Underground for The O Greenwich Peninsula Church Street P 161 79 R Connections with National Rail 220 T Millennium Village Charlton Woolwich A T H E V I S TA H E R V Î Connections with Docklands Light Railway Oval Square Ferry I K S T Royaloya Blackheathack MMiddle A Â Connections with river boats A Parkk V Goolf CourseCo Connections with Emirates Air Line 1 E 174 N U C Woolwich Common Middle Park E O Queen Elizabeth Hospital U Primary School 90 ST. KEVERNEROAD R T 123 A R Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus 172 O Well Hall Road T service. The disc !A appears on the top of the bus stop in the E N C A Arbroath Road E S King John 1 2 3 C R street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). -

School Case Studies: 2006-2011

School case studies: 2006-2011 School case studies: 2006-2011 Creativity, Culture and Education Great North House, Sandyford Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ND www.creativitycultureeducation.org Registered charity no.1125841 Registered company no.06600739 July 2012 Contents Introduction 03 Introduction David Parker, Director of Research and Impact – Creativity, Culture and 06 Case Study 1 The Arnold Centre, Rotherham Education (CCE) 14 Case Study 2 Lancasterian Special School, West Didsbury 22 Case Study 3 New Invention Junior School, Willenhall 28 Case Study 4 Minterne Community Junior School, Sittingbourne 36 Case Study 5 Penn Hall Special School, Wolverhampton 44 Case Study 6 McMillan Nursery School, Hull 52 Case Study 7 Prudhoe Community High School, Prudhoe The case studies that follow give an insight into 60 Case Study 8 Our Lady of Victories Catholic Primary School, Keighley Creative Partnerships continues to exert an how Creative Partnerships has had a lasting effect 68 Case Study 9 Fulbridge Primary School, Peterborough influence on education through the shared within schools. Each narrative offers an honest 77 Case Study 10 Thomas Tallis School, Blackheath experience of teachers, creative professionals reflection of where schools are now that the 85 Case Study 11 Accrington Academy, Accrington and young people who participated in the programme and the levels of financial support it programme until it ended in summer 2011. once offered are no longer available. They are While the programme is complete, the stories of adaptation and assimilation and are practice continues to develop in new and testimony to the vision and commitment of education professionals who are driven to help interesting ways. -

Why We Have 'Mixed Communities' Policies and Some Difficulties In

Notes for Haringey Housing and Regeneration Scrutiny Panel Dr Jane Lewis London Metropolitan University April 3rd 2017 Dr Jane Lewis • Dr Jane Lewis is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Social Policy at London Metropolitan University. She has worked previously as a lecturer in urban regeneration and in geography as well as in urban regeneration and economic development posts in local government in London. Jane has wide experience teaching at under-graduate and post-graduate levels with specific expertise in urban inequalities; globalisation and global inequalities; housing and urban regeneration policy and is course leader of the professional doctorate programme in working lives and of masters’ courses in urban regeneration and sustainable cities dating back to 2005.Jane has a research background in cities and in urban inequalities, urban regeneration policy and economic and labour market conditions and change. aims • 1. Invited following presentation Haringey Housing Forum on concerns relating to council estate regeneration schemes in London in name of mixed communities polices • 2. Senior Lecturer Social Policy at LMU (attached note) • 3. Terms of reference of Scrutiny Panel focus on 1and 2 – relating to rehousing of council tenants in HDV redevelopments and to 7 – equalities implications Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV) and Northumberland Park • ‘development projects’ proposed for the first phase of the HDV include Northumberland Park Regeneration Area – includes 4 estates, Northumberland Park estate largest • Northumberland Park -

Kidbrooke Village Case Study

A place in the making Kidbrooke Village urn left out of Kidbrooke station and follow the road round towards Sutcliffe Park. For anyone that knew T • 4,000 homes by 2028: already over 500 the Ferrier Estate, it is a strange experience. The concrete blocks have gone. The sense of empty isolation has are complete, including 344 affordable, vanished. In its place is the hum of construction. and another 300 started on site. Across the road are new modern apartment blocks – • large windows, balconies and smart red brick – set Over 2,500 jobs created so far in immaculate landscaping with lush grass, scarlet in construction; 34 apprenticeships; geraniums and other brightly coloured bedding plants. and 57 permanent local jobs. It feels almost manicured. • This is Kidbrooke Village, one of the most ambitious £36m invested in infrastructure so far, regeneration schemes in Europe. The masterplan will cost out of a projected total of £143m, helping £1bn to deliver and transform 109 hectares of deprived to reclaim 11.3 hectares of brownfield south-east London, an area little smaller than Hyde Park, into a stunning modern community. land to date and create 35 hectares of parkland and sports pitches. Over a period of 20 years, 4000 new homes will be delivered. But the result will be more than just housing • 170 new, award-winning homes – this is a place in the making. There will be a complete mix of tenures and facilities, carefully matching the needs specifically designed as senior living of families, renters, first time buyers and older people for older people. -

THE VIABILITY of LARGE HOUSING DEVELOPMENTS: Learning from Kidbrooke Village 26 April 2013

THE VIABILITY OF LARGE HOUSING DEVELOPMENTS: Learning from Kidbrooke Village 26 April 2013 PRODUCED BY CONTENTS URBED Context.........................................3 26 Store Street London WC1E 7BT Connectivity.................................3 t. 07714979956 e-mail: [email protected] Community..................................4 website: www.urbed.coop Character.....................................7 This report was written by Dr Nicholas Falk , Founding Director, URBED Climate proofing..........................8 May 2013 Collaboration and cash flow........9 Our special thanks to John Anderson, Theresa Brewer, Conclusions................................10 Penny Carter of Berkeley for their hospitality and insight into the development. Delegates....................................12 TEN Group TEN is a small group of senior local government officers in London who have met regularly over eight years to share ideas and exchange knowledge on how to achieve urban renaissance. Using the principle of looking and learning they visit pioneering projects to draw out lessons that can be applied in their own authorities. In the proc- ess the members develop their skills as urban impresarios and place-makers, and are able to build up the capac- ity of their authorities to tackle major projects. Photographs: unless otherwise stated provided by TEN Group members and URBED Ltd Front cover: Top left - SUDs at Blackheath quarter Middle - John Anderson shows the group around Right - Phase 1 housing Copyright URBED/TEN Group 2012 2012-13 Members include: -

Download (591Kb)

This is the author’s version of the article, first published in Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, Volume 8 / Number 2 / Winter, 2014-15, pp. 133- 144 (12). https://www.henrystewartpublications.com/jurr Understanding and measuring social sustainability Email [email protected] Abstract Social sustainability is a new strand of discourse on sustainable development. It has developed over a number of years in response to the dominance of environmental concerns and technological solutions in urban development and the lack of progress in tackling social issues in cities such as inequality, displacement, liveability and the increasing need for affordable housing. Even though the Sustainable Communities policy agenda was introduced in the UK a decade ago, the social dimensions of sustainability have been largely overlooked in debates, policy and practice around sustainable urbanism. However, this is beginning to change. A combination of financial austerity, public sector budget cuts, rising housing need, and public & political concern about the social outcomes of regeneration, are focusing attention on the relationship between urban development, quality of life and opportunities. There is a growing interest in understanding and measuring the social outcomes of regeneration and urban development in the UK and internationally. A small, but growing, movement of architects, planners, developers, housing associations and local authorities advocating a more ‘social’ approach to planning, constructing and managing cities. This is part of an international interest in social sustainability, a concept that is increasingly being used by governments, public agencies, policy makers, NGOs and corporations to frame decisions about urban development, regeneration and housing, as part of a burgeoning policy discourse on the sustainability and resilience of cities. -

London's Housing Struggles Developer&Housing Association Dec 2014

LONDON’S HOUSING STRUGGLES 2005 - 2032 47 68 30 13 55 20 56 26 62 19 61 44 43 32 10 41 1 31 2 9 17 6 67 58 53 24 8 37 46 22 64 42 63 3 48 5 69 33 54 11 52 27 59 65 12 7 35 40 34 74 51 29 38 57 50 73 66 75 14 25 18 36 21 39 15 72 4 23 71 70 49 28 60 45 16 4 - Mardyke Estate 55 - Granville Road Estate 33 - New Era Estate 31 - Love Lane Estate 41 - Bemerton Estate 4 - Larner Road 66 - South Acton Estate 26 - Alma Road Estate 7 - Tavy Bridge estate 21 - Heathside & Lethbridge 17 - Canning Town & Custom 13 - Repton Court 29 - Wood Dene Estate 24 - Cotall Street 20 - Marlowe Road Estate 6 - Leys Estate 56 - Dollis Valley Estate 37 - Woodberry Down 32 - Wards Corner 43 - Andover Estate 70 - Deans Gardens Estate 30 - Highmead Estate 11 - Abbey Road Estates House 34 - Aylesbury Estate 8 - Goresbrook Village 58 - Cricklewood Brent Cross 71 - Green Man Lane 44 - New Avenue Estate 12 - Connaught Estate 23 - Reginald Road 19 - Carpenters Estate 35 - Heygate Estate 9 - Thames View 61 - West Hendon 72 - Allen Court 47 - Ladderswood Way 14 - Maryon Road Estate 25 - Pepys Estate 36 - Elmington Estate 10 - Gascoigne Estate 62 - Grahame Park 15 - Grove Estate 28 - Kender Estate 68 - Stonegrove & Spur 73 - Havelock Estate 74 - Rectory Park 16 - Ferrier Estate Estates 75 - Leopold Estate 53 - South Kilburn 63 - Church End area 50 - Watermeadow Court 1 - Darlington Gardens 18 - Excalibur Estate 51 - West Kensingston 2 - Chippenham Gardens 38 - Myatts Fields 64 - Chalkhill Estate 45 - Tidbury Court 42 - Westbourne area & Gibbs Green Estates 3 - Briar Road Estate -

Secondary Schools in Royal Greenwich SECONDARY 2019/20 Booklet Is Available at SCHOOLS in ROYAL GREENWICH 2019/20

The Secondary Schools in Royal Greenwich SECONDARY 2019/20 booklet is available at SCHOOLS www.royalgreenwich.gov.uk/admissions IN ROYAL GREENWICH 2019/20 ...................................... An introduction Closing date for applications: 31 October 2018 www.royalgreenwich.gov.uk/admissions 18354S-Introduction to Secondary Schools in Royal Greenwich 2019-20.indd 1 06/09/2018 12:02 WAY SS O R C C A FINDING Y R L A Y W L L E R A O A R D North T A SCHOOL N Greenwich E C H AY A ....................................... R Y W WA R E N O B N ASTER L ER W A T C S M E A K J W M N W IL O A LE N R Bus routes and rail stations. L N L I U W M TU W A A Y N Y N OLW STREET E WO ICH HIGH L T B E J E N C E O S CH TR R A R O UR S E M E H W CH S T S U OO F T C LWI CH N OR E T D P E S N H W ’S TRE N ET TEAD ROAD T I I E D LUMS E L E P R 6 S R N D 0 O E N 2 G R A N N O W T A S G E E T A T N E P B LI E N 20 U R L R N P GS E ST H 6 R BY WAY D E W A C A E I P L O O T L R A LW U L W M C E O ST L H H N E O EA IC A C D K A LW RY PL W HIG O RTILLE H N W WO A D ST R E K R EE C T E T C 06 H H 2 A O A A 2 C 0 H A 6 A P L E R E R I B L L L L D T I A L O H 2 A D 06 N Eltham Hill School N BO Charlton A A C S H R T 1 H T A A U A G L 0 E 2 L Bus routes: 122, 124, 126, 132, 2 R H D C 0 H H E A L 9 ILL Cutty Sark O T NIG A L 2 R HTINGALE 06 A IT R PLACE PL A N L UM 160, 161, 233, 286, 314, 321, S G Westcombe E W L GE CHARLTON PK RD TEAD CO FA LA AD M IL O N E K I A V R MO RO D ING C R Park E AD A ’ 624, 660, 816 T HA L S H K H S HA E IG H Maze Hill T T H HW A ROAD A M EEK -

B16 Kidbrooke - Eltham - Bexleyheath Daily Ferrier Estate Church

B16 Kidbrooke - Eltham - Bexleyheath Daily Ferrier Estate Church Kidbrooke KidbrookeStation Ê Eltham GreenEltham WestmountRochester Road FalconwoodWay Falconwood Station ÊHook Parade LaneWestwoodWelling Lane CornerBexleyheath Bexleyheath Shopping Centre Bus Garage Monday - Friday Kidbrooke Station Ê 0620 0640 0700 0712 0724 0736 0751 0807 0822 0837 0852 0906 1421 1436 1736 Kidbrooke Ferrier Estate 0624 0644 0704 0716 0728 0741 0756 0812 0827 0842 0857 0911 Then 1427 1442 Then 1741 Eltham Church 0633 0653 0713 0725 0738 0753 0808 0824 0839 0854 0909 0923 every 1438 1453 every 1753 Falconwood Station Ê 0641 0701 0721 0734 0750 0805 0820 0836 0851 0906 0921 0935 15 1450 1505 15 1805 Falconwood Parade 0644 0704 0724 0738 0754 0809 0824 0840 0855 0910 0925 0939 minutes 1454 1508 mins 1808 Welling Corner 0649 0709 0729 0746 0802 0817 0832 0848 0903 0918 0933 0947 until 1502 1515 until 1815 Bexleyheath Shopping Centre 0656 0716 0737 0756 0812 0827 0842 0858 0913 0928 0943 0958 1513 1526 1826 Bexleyheath Bus Garage 0658 0718 0739 0758 0814 0829 0844 0900 0915 0930 0945 1000 1515 1528 1828 Kidbrooke Station Ê 1751 1806 1821 1836 1850 1908 1928 1948 2011 2036 2105 0035 Kidbrooke Ferrier Estate 1756 1811 1826 1840 1854 1912 1932 1952 2015 2040 2109 Then 0039 Eltham Church 1808 1823 1838 1852 1904 1922 1942 2002 2024 2049 2118 every 0048 Falconwood Station Ê 1820 1835 1847 1900 1913 1931 1951 2010 2032 2057 2126 30 0056 Falconwood Parade 1823 1838 1850 1903 1916 1934 1954 2013 2035 2100 2129 minutes 0059 Welling Corner 1830 1844 1856 1909 1922 1940 -

A Force for Good

A FORCE FOR GOOD Welcome Placemaking is a force for good in this country. Giving people a home. Creating strong communities. Foreword Generating jobs and growth. Making our society better in many different ways. It is a driving force behind this nation’s wealth and prosperity. Creating successful places transforms people’s lives, from the country to the suburbs and from council estates to the high street. It is good for the people who live and work in each community; and it benefits countless others who now enjoy fantastic public realm, playing in the parks and using the shops and facilities, as well as public transport and services funded by new development. This story does not get told loudly enough. Right across the country, councils and communities are working together with our industry, turning vacant and derelict sites into handsome places that contribute positively to life in Britain. There is a lot for everyone to be proud of. As a business, Berkeley is always learning and listening hard to what people say. On our 40th anniversary, we also want to celebrate the communities we have built together and the importance of housebuilding to all our lives. Tony Pidgley CBE, Chairman Rob Perrins, Chief Executive 1 Contents 2 Contents CHAPTER 01 The story of Berkeley CHAPTER 02 Working together CHAPTER 03 Spaces to enjoy CHAPTER 04 Places for everyone CHAPTER 05 Jobs and training CHAPTER 06 Getting around CHAPTER 07 Restoring our heritage CHAPTER 08 Transforming lives CHAPTER 09 It takes a team to deliver CHAPTER 10 The future 3 The story