View Big Tech Symposium Transcript (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Global Media Journal German Edition From the field An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation Andrej Školkay1 Abstract: This is a study of suggested approaches to social media regulation based on an explora- tory methodological approach. Its first aim is to provide an overview of the global and local debates and the main arguments and concerns, and second, to systematise this in order to construct taxon- omies. Despite its methodological limitations, the study provides new insights into this very rele- vant global and local policy debate. We found that there are trends in regulatory policymaking to- wards both innovative and radical approaches but also towards approaches of copying broadcast media regulation to the sphere of social media. In contrast, traditional self- and co-regulatory ap- proaches seem to have been, by and large, abandoned as the preferred regulatory approaches. The study discusses these regulatory approaches as presented in global and selected local, mostly Euro- pean and US discourses in three analytical groups based on the intensity of suggested regulatory intervention. Keywords: social media, regulation, hate speech, fake news, EU, USA, media policy, platforms Author information: Dr. Andrej Školkay is director of research at the School of Communication and Media, Bratislava, Slovakia. He has published widely on media and politics, especially on political communication, but also on ethics, media regulation, populism, and media law in Slovakia and abroad. His most recent book is Media Law in Slovakia (Kluwer Publishers, 2016). Dr. Školkay has been a leader of national research teams in the H2020 Projects COMPACT (CSA - 2017-2020), DEMOS (RIA - 2018-2021), FP7 Projects MEDIADEM (2010-2013) and ANTICORRP (2013-2017), as well as Media Plurality Monitor (2015). -

The Big Tech Antitrust Bills

The Big Tech Antitrust Bills August 13, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46875 SUMMARY R46875 The Big Tech Antitrust Bills June 23, 2021 Over the past decade, Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple have revolutionized the digital economy. Many people now use the products and services of these “Big Tech” firms on a daily Jay B. Sykes basis. Facebook boasts more than 2 billion monthly active users. Google licenses the world’s Legislative Attorney most popular mobile operating system and runs a search engine that processes 3½ billion searches a day. Amazon operates the largest online marketplace, a massive logistics network, and a leading cloud-computing company. Apple has popularized the smart phone to such a degree For a copy of the full report, that consumers have grown accustomed to carrying supercomputers in their pockets. please call 7-5700 or visit www.crs.gov. While the Big Tech firms have plainly made important technological breakthroughs, their business practices have attracted scrutiny from antitrust regulators and some Members of Congress. In October 2020, the House Committee on the Judiciary’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law concluded a 16-month investigation of these practices, which culminated in a 450-page report recommending a range of measures to address the firms’ allegedly anticompetitive conduct. Many of those measures have now taken legislative form. In June 2021, the House Committee on the Judiciary ordered to be reported a series of antitrust bills directed at Big Tech. The legislative package represents the most comprehensive effort to date to tackle competition issues in the digital economy. -

The 2020 Election Coup

The 2020 Election Coup How the Democrats and Their Allies Stole the 2020 Presidential Election David Walker Copyright 2021 by Open Horizons Open Horizons P O Box 2887 Taos NM 87571 575-751-3398 Web: https://MyIncredibleWebsite.com Contents Introduction A Transparent Fair Election? The Lack of Evidence! Really? The Too Many Voters Cheat The Vote Dump New Ballot Discoveries Pause the Count Controversy The Endless Countdown Mail-In Ballot Shenanigans Margins Out of This World The Ghost Gambit, aka Dead People Voting The Alien FlimFlam The Vacated Movement The Down-Ballot Void The Bellwether Break-Down Impossible Probabilities The Poll Watcher Torture The Poll Worker as Voter Election Officials as Violators of the Law Witness Intimidation The Ballot Dump Mail-In Ballot Rejections SharpieGate The Military Mission The China Connection The Nursing Home No-No The Disability Dodge The Goal Post Gambit Change the Rules Ploy The Miracle Cure The Tech Bubble Trick The Night Before Christmas Caper The Glitch Gimmick Unverified Signatures Scam Competitor Cancellations Early Voter Remorse Insider Trading Information Buy Votes Scheme The Threat Matrix The Stolen Ballot Jig The Time Travel Twist The Postal Dis-Service Social Media Censorship Voter Suppression by Polls Non-Polling Metrics Media Mayhem Pinocchio’s Pretense The Vandal Veto The Georgia Run-Off What Are We to Do? It’s in the Hands of God Exhibit I: The Doug Ross Graphics Exhibit II: The Expert Affidavit Exhibit III: Billionaires Buy the Election Exhibit IV: The Pennsylvania Flim-Flam Exhibit V: Judge Rules 9 Ways Election Officials Failed Exhibit VI: Election Commentary by John Droz, Jr. -

'Big Tech Cashing in from Evil'

ARAB TIMES, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 20, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Film Poised for change Ben-Adir ‘breaks’ out as Malcolm X LOS ANGELES, Jan 19, (AP): British actor King- sley Ben-Adir may not be a household name yet, but that’s poised to change with his scene-stealing performance as Malcolm X in Regina King’s “One Night in Miami....” The fi lm, which imagines an electric meeting between the civil rights icon, Sam Cooke, Cassius Clay and Jim Brown in February 1964, is currently available on Prime Video. The 35-year-old has been a working actor for over a decade and has had more than a few heartbreaks and near-breaks along the way. In his fi rst fi lm, “World War Z,” his speaking line with Brad Pitt was unceremoniously cut. Then there was the Ang Lee Muhammad Ali fi lm that he spent years testing and months in active training for (he was to play Ali) that ended up losing its fi nancing. “One Night in Miami...” was almost a missed oppor- tunity, too. His agents fi rst suggested him for Clay. He declined (“I felt too old”) but said to call him if anything happened to the actor playing Malcolm. Ben-Adir said he was partially joking, but that Ben-Adir call did come. He offi cially got the part just 12 days before he was due on set. “I thought, I don’t know if I can prepare Malcolm X in 12 days,” Ben-Adir said. “Then I was like, ‘I have to do it.’” Ben-Adir spoke to The Associated Press - hours before he’d pick up the breakthrough actor award at the Gotham Awards - about fi nding the humanity in the icon and the tricky logistics of playing both Malcolm X and Barack Obama at the same time. -

HOPE AWARDS for EFFECTIVE COMPASSION PROFILES in POVERTY-FIGHTING What WORLD Looks for in Effective Compassion Coverage by Sophia Lee

EARNING YOUR TRUST, EVERY DAY. 07.31.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 14 HOPE AWARDS “THE HARDEST THING TO SEE IS THE LOST GENERATION, THE CHILDREN OF THIS WAR. THEY HAVE NO FUTURE.” —SYRIA’S CIVIL WAR CONTINUES, P. 38 P. CONTINUES, WAR CIVIL —SYRIA’S FUTURE.” NO HAVE THEY WAR. THIS OF CHILDREN THE GENERATION, LOST THE IS SEE TO THING HARDEST “THE FOR EFFECTIVE COMPASSION P.46 v36 14 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/13/21 4:31 PM SamaritanMinistries.org/WORLD . 877.578.6787 v36 14 COVER+TOC.indd 2 7/13/21 2:22 PM FEATURES 07.31.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 14 38 A DECADE OF DESTRUCTION Syria’s ongoing civil war, now in its 10th year, is shaping a generation to imagine nothing but war by Mindy Belz 46 2021 HOPE AWARDS FOR EFFECTIVE COMPASSION PROFILES IN POVERTY-FIGHTING What WORLD looks for in effective compassion coverage by Sophia Lee OMAR HAJ KADOUR/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES 07.31.21 WORLD v36 14 COVER+TOC.indd 1 7/13/21 4:04 PM DEPARTMENTS 07.31.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 14 5 MAILBAG 6 NOTES FROM THE CEO 21 Scarlett Johansson (left) and Florence Pugh in Black Widow Dispatches Culture Notebook 11 NEWS ANALYSIS 21 MOVIES & TV 69 BUSINESS Turmoil in Haiti: The BLACK WIDOW Black Widow, The Boss Ships in limbo: president’s assassination Baby: Family Business, Weighing the hidden plunges the nation IS A FAMILY The Tomorrow War, costs of the cruise into further chaos The Mysterious Benedict industry shutdown DRAMA IN Society, Summer of Soul 13 BY THE NUMBERS 71 LIFESTYLE WHICH BROKEN 26 BOOKS 14 HUMAN RACE WOMEN TRY A sorrowful history: 72 SPORTS Books on abortion 15 QUOTABLES TO COME TO 28 CHILDREN'S BOOKS Voices 16 QUICK TAKES TERMS WITH 30 Q&A 8 Joel Belz THE WORLD. -

717 Sdc 01 Layout 1

CONCERTUL DE ANUL NOU 2021 CRISTIAN FULAȘ – DE LA VIENA IOȘCA „Suplimentul de cultură“ publică în avanpremieră un fragment din acest roman, care va apărea în curând în colecția „Ego. Proză“ a Editurii Polirom. O ediție istorică, cu o orchestră încă prea albă. PAGINA 11 PAGINA 12 CELE MAI VÂNDUTE TITLURI POLIROM ÎN ANUL 2020 ANUL XVII w NR. 717 w 16 – 22 IANUARIE 2021 w REALIZAT DE EDITURA POLIROM ȘI ZIARUL DE IAȘI PAGINILE 2-3 INTERVIU CU SCRIITORUL VASILE ERNU „ISTORIA CELOR ÎNVINȘI E MAI SPECTACULOASĂ DECÂT CEA A ÎNVINGĂTORILOR“ PAGINILE 8-9 ANUL XVII NR. 717 2 actualitate 16 – 22 IANUARIE 2021 www.suplimentuldecultura.ro Cele mai vândute titluri Polirom în anul 2020 Deși atipic și plin de provocări pentru întreaga industrie de carte, romanțate, Biblioteca Polirom, Junior, Top 10+, Eseuri și confesiuni, 2020 a fost un an prolific pentru Polirom, peste 450 de noi Hexagon etc. Circa 45 de domenii editoriale: literatură română și titluri regăsindu-se la final de an aniversar – 25 de ani de universală, thriller, literatură polițistă, suspans, document, eseu, existență – în portofoliul editurii. În ciuda contextului pandemic economie, istorie, filosofie, psihologie, psihanaliză, religie și global, care a afectat, inevitabil, și piața de carte din România, spiritualitate, științe, științe politice, științe umaniste, artă, Polirom a continuat să-și dezvolte principalele linii editoriale, cinema, dicționare, limbi și enciclopedii, informatică și Internet, respectându-și statutul de editură generalistă de prim rang, carte școlară, sănătate și dietetică, medicină reviste etc. cu peste 8.000 de titluri publicate până în prezent în cele În topul celor mai vândute titluri Polirom în anul 2020, top condus mai îndrăgite colecții și din cele mai variate domenii. -

Meltdown of Liberty

Workshop Study 14 Meltdown of Liberty Introduction Seeing the principles of America’s founding that shaped our country becoming severely weakened, former President Trump set up a 1776 Commission, chaired by Larry P. Arnn (President of Hillsdale College). It aimed to bring back to America the unifying ideals stated in the Declaration of Independence. • Biden cancelled the Commission. • He believes in: 1. A constant evolving of group rights (protected classes), i.e., the meaning of freedom could change. 2. A fourth branch of government composed of independent agencies staffed by “experts” who are insulated from political accountability [the “deep state” already exists]. 3. Socialistic-run federal government that not only rules over the states but micromanages individual citizens (a Democratic dream since “cultural Marxism” rose). 4. Stifling dissent.1 At no time in American history has “naked censorship” been carried out at so many levels as today. Not only is “Big Tech” helping to crush free speech but 250 book publishers have stated, “No book deals for traitors.” And who are traitors? • Those who criticize gender dysphoria, sex workers, abortions, restrictions of certain culturally offensive words, such as “he” or “she” or the anti-God socialistic agenda for America. • Google closed down 20,000 accounts that took Covid-19 positions they didn’t like. Joe Biden’s administration has also declared “war on another terror” – not on the anarchists, like the Marxist revolutionary groups Antifa or Black Lives Matter, which led out in much of the rioting, burning, vandalizing, looting, assaulting and killing in America’s cities during 2020. 1 Saba, Mike; Whistleblower, January 2021, pp. -

Compelling Code: a First Amendment Argument Against Requiring Political Neutrality in Online Content Moderation

42993-crn_106-2 Sheet No. 80 Side A 03/12/2021 06:20:48 \\jciprod01\productn\C\CRN\106-2\CRN204.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-FEB-21 11:00 NOTE COMPELLING CODE: A FIRST AMENDMENT ARGUMENT AGAINST REQUIRING POLITICAL NEUTRALITY IN ONLINE CONTENT MODERATION Lily A. Coad† The Internet’s most important law is under attack. Sec- tion 230, the statute that provides tech companies with legal immunity from liability for content shared by their users, has recently found its way into the spotlight, becoming one of to- day’s most hotly debated topics. The short but mighty provi- sion ensures that tech companies can engage in socially beneficial content moderation (such as removing hate speech or flagging posts containing misinformation) without risking enormous liability for any posts that slip through the cracks. Without it, companies would be faced with the impossible task of screening every post, tweet, and comment for potential liability. In spite of the essential role Section 230 plays in the mod- ern Internet, lawmakers from across the political spectrum have condemned the statute––and the tech giants that it pro- tects. While Democrats say social media companies should be held responsible for failing to quash the misinformation and radicalization on their platforms, many Republicans believe that social media is biased against conservative views. 42993-crn_106-2 Sheet No. 80 Side A 03/12/2021 06:20:48 In 2019, Senator Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) introduced a bill that exemplifies conservatives’ criticisms of big tech and Sec- tion 230. The Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act seeks to eradicate the alleged “anti-conservative bias” on so- cial media platforms by requiring large tech companies to maintain politically neutral content moderation algorithms and † B.A., Duke University, 2018; J.D., Cornell Law School, 2021; Publishing Editor, Cornell Law Review, Vol. -

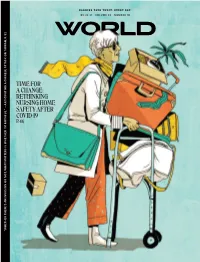

Time for a Change: Rethinking Nursing Home Safety After

EARNING YOUR TRUST, EVERY DAY. 05.22.21 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 10 TIME FOR A CHANGE: RETHINKING NURSING HOME SAFETY AFTER COVID-19 P. 4 6 “WHETHER THERE’S AN INVASION OR NOT, WHAT MATTERS IS WHETHER I’M FAITHFUL.” —ANTICIPATING A CHINESE ATTACK ON TAIWAN, P. 52 P. TAIWAN, ON ATTACK CHINESE A —ANTICIPATING FAITHFUL.” I’M WHETHER IS MATTERS WHAT NOT, OR INVASION AN THERE’S “WHETHER The time has come to produce a visual and interactive Bible that can be easily translated into any of the world’s 7,000 languages and distributed around the globe for FREE! • iBIBLE will cover the entire Biblical narrative from Genesis to Revelation, RevelationMedia is now in production presented as a single cohesive story. of iBIBLE: the world’s first animated • iBIBLE will include an estimated 150 Bible that can be viewed online, chapters, and the vibrant animation and through a portable projector, or on any dramatic audio spans 18 hours. of the world’s five billion cell phones. iBIBLE breaks the literacy barrier • iBIBLE uses the Holy Bible alone for by communicating Biblical content its scripts to present the true narrative through animation, audio, subtitles—all of Scripture. Nothing added, nothing in an interactive format. changed. If 80% of unreached Are you willing to help? iBIBLE is solely supported by the generous contributions of Christians committed to reaching the world’s unreached with God’s Word in a format they can understand. people cannot read, why Donations are fully tax deductible* and will be used 100% in the creation of iBIBLE. -

Revisiting the New Tech Lifeless Religion

Notes: May 29 2021 Start: 10 AM Order of service: 1. Meet and Greet 2. Introduction (if new people) 3. Ma Tovu 4. Open in Prayer for service 5. Liturgy – Sh'ma + 6. Announcements 7. Praise and Worship Songs 8. Message 9. Aaronic Blessing 10. Kiddush 11. Oneg Children's Blessing: Transliteration: Ye'simcha Elohim ke-Ephraim ve hee-Menashe English: May God make you like Ephraim and Menashe Transliteration: Ye'simech Elohim ke-Sarah, Rivka, Rachel ve-Leah. English: May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. Introduction: Revisiting the New Tech Lifeless Religion Two months ago I shared with you the concerns and dangers of what has been identified as the Religion of Technology and thus conveyed that we should beware of it. http://www.shalommaine.com/sermon_notes_pdf/Beware_of_The_New_Tech_Religion.pdf I had shared with you... What seemed implausible at the time has become a reality and thus part of our everyday life. We did not have to go hundreds of years into the future but merely a generation or two. The development of artificial intelligence (a wide-ranging branch of computer science concerned with building smart machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence) is the pursuit of nations with the intent of gaining control of people. Yet, the romanticized aspect of trans-humanism is extending one's life. Yet is this pursuit of extending life truly life affirming? Does it acknowledge or affirm the Giver of Life? Last Shabbat we proclaimed in this congregation Chaim Ha Kayits – The Summer of Life. Yet, the powers that be, Government, The Media, Big Tech, and various Corporations are not intending to promote life but rather control one's life. -

A Guide to Boycotting EVENT/ CORPORATION/ ORGANIZATION

A Guide to Boycotting Helpful List in Regaining our Country. Remember this is a war, and this is a legal warfare against all the following companies, etc. If the item to be boycotted is in red, it is to be avoiding at all costs. In accordance with the below listed website, consider the content on this page as public domain on your own website, blog, or social media page. For more and/or additional information, please refer to: https://www.investingadvicewatchdog.com/Liberal-Companies-Boycott.html Patriots: PLEASE Follow the Boycott Chart and the Boycott List. The most detrimental ones to us are labeled, “Enemy of the People” and are in red. Let Us Do the “Canceling of the Culture” of the Socialist/Communist agenda which is threating our country and our freedom. We must use boycotting to help fight this war. Please keep this list. Boycotting is one way to fight legally for our country. After all, we are in a fight to regain and keep our country. Our forefathers fought hard for our country. Now, we must fight to keep it. This is a new type of fight against our enemies. Boycott as many as possible , if not all. Sometimes, if not a choice, choose between the lesser of two evils. Small list at the end of business to buy from. EVENT/ CORPORATION/ REASON ORGANIZATION/ PERSON/ PRODUCT, ETC. TECH TYRANNY In a vile attack on free speech, Amazon kicked Parler off its AWS web hosting service. Cancel your Prime membership if Amazon.com…”Enemy of you have one! Jeff Bezos owns the radical left-wing Washington Post and has resisted Trump's Muslim immigration ban, We the People.” putting our country at risk. -

New York Times Best Seller List– Week of May 23, 2021

New York Times Best Seller List – Week of May 23, 2021 FICTION NONFICTION TW LW WOL TW LW WOL THE LAST THING HE TOLD ME, by Laura Dave. Hannah KILLING THE MOB, by Bill O’Reilly. 10th book in the O/O Hall discovers truths about her missing husband and bonds -- 1 conservative commentator’s Killing series looks at 1 O/O -- 1 with his daughter from a previous relationship. 1 organized crime in the United States during the 20th 21ST BIRTHDAY, by James Patterson. 21st book in the century. O/O WHAT HAPPENED TO YOU?, by Bruce D. Perry. An 2 Women’s Murder Club series. New evidence changes the -- 1 investigation of a missing mother. 2 approach to dealing with trauma that shifts an 1 2 SOOLEY, by John Grisham. Samuel Sooleymon receives a essential question used to investigate it. basketball scholarship to North Carolina Central and THE PREMONITION, by Michael Lewis. Stories of 3 1 2 O/O determines to bring his family over from a civil war-ravaged 3 skeptics who went against the official response of the -- 1 South Sudan. Trump administration to the outbreak of Covid19 FINDING THE MOTHER TREE, by Suzanne Simard. PROJECT HAIL MARY, by Andy Weir. Ryland Grace O/O O/O An ecologist describes ways trees communicate, -- 1 4 awakes from a long sleep alone and far from home, and the -- 1 4 fate of humanity rests on his shoulders. cooperate and compete. THE BOMBER MAFIA, by Malcolm Gladwell. A look THE HILL WE CLIMB, by Amanda Gorman. The poem read O/O 5 on President Joe Biden's Inauguration Day, by the youngest 2 6 5 at the key players and outcomes of precision bombing 2 2 poet to write and perform an inaugural poem.