Foster Care in Early Childhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Safety and Stability for Foster Children: a Developmental Perspective

Children, Families, and Foster Care Safety and Stability for Foster Children: A Developmental Perspective Brenda Jones Harden SUMMARY Children in foster care face a challenging jour- ders, compromised brain functioning, inade- ney through childhood. In addition to the quate social skills, and mental health difficul- troubling family circumstances that bring them ties. into state care, they face additional difficulties ◗ Providing stable and nurturing families can within the child welfare system that may further bolster the resilience of children in care and compromise their healthy development. This ameliorate negative impacts on their develop- article discusses the importance of safety and mental outcomes. stability to healthy child development and reviews the research on the risks associated with mal- The author concludes that developmentally- treatment and the foster care experience. It finds: sensitive child welfare policies and practices designed to promote the well-being of the ◗ Family stability is best viewed as a process of whole child, such as ongoing screening and caregiving practices that, when present, can assessment and coordinated systems of care, are greatly facilitate healthy child development. needed to facilitate the healthy development of ◗ Children in foster care, as a result of exposure children in foster care. to risk factors such as poverty, maltreatment, and the foster care experience, face multiple Brenda Jones Harden, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the Institute for Child Study in the Department of threats to their healthy development, includ- Human Development at the University of Maryland, ing poor physical health, attachment disor- College Park. www.futureofchildren.org 31 Jones Harden rotecting and nurturing the young is a uni- care due to their exposure to maltreatment, family versal goal across human cultures. -

HELP: a Handbook for Kentucky Grandparents and Other Relative

HELP A HANDBOOK FOR KENTUCKY GRANDPARENTS AND OTHER RELATIVE CAREGIVERS ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOUNDATION LEGAL HELPLINE FOR OLDER KENTUCKIANS LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY BLUEGRASS AREA AGENCY ON AGING AND INDEPENDENT LIVING 699 PERIMETER DRIVE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40517 (859) 269-8021 This project is funded, in part, under a contract with the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, with funds from the Administration on Aging and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. HELP A HANDBOOK FOR KENTUCKY GRANDPARENTS AND OTHER RELATIVE CAREGIVERS WRITTEN BY: David Godfrey, J.D. Melanie Beckwith Jesse Reid Hodgson Jeffery Mahoney Robert Stith EDITED BY: Laura B. Grubbs Bluegrass Area Development District Bluegrass Area Agency on Aging 699 Perimeter Drive Lexington, Kentucky 40517-4120 859-269-8021 ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOUNDATION LEGAL HELPLINE FOR OLDER KENTUCKIANS Lexington, Kentucky This project is funded, in part, under a contract with the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, with funds from the Administration on Aging and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Please feel free to copy and distribute the information in this handbook for any non-commercial purpose. REVISION DATE: JANUARY 2007 EVERY EFFORT WAS MADE TO MAKE THIS DOCUMENT CURRENT THROUGH JANUARY 2007. PROGRAMS AND POLICES CHANGE, YOU SHOULD ALWAYS VERIFY THAT THE INFORMATION IS CURRENT BEFORE PROCEEDING. THE MORE TIME THAT PASSES, THE GREATER THE LIKELIHOOD THAT INFORMATION IS OUT OF DATE. ii INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Each year thousands of grandparents and other relatives in Kentucky assume the responsibility of raising children for biological parents who are unable or unwilling or to be parents. -

Teens in Foster Care and Their Babies

Teens in Foster Care and Their Babies 2013 If you are a pregnant or parenting teenager in foster care, you may have some questions or concerns. Being a teen parent can be stressful, and the added demands of the foster care system might leave you feeling confused or concerned for your baby’s future. This brochure answers some common questions and explains what your rights are as a pregnant or parenting teen in foster care. Family Planning Teens in foster care have the same right as other teens to obtain advice on birth control, family planning, and pregnancy tests without the consent of anyone else. To get these services, contact Family Planning (800) 942-1054 or Planned Parenthood (800) 576-5544. HIV Testing If you are 12 or older, you can get tested for HIV/AIDS without anyone else’s permission and without giving permission for others to be told. However, if you tell a DCFS social worker that you are HIV+ or have AIDS, the social worker must tell others. What If I Become Pregnant While I’m a Court Dependent? The decision regarding how to handle your pregnancy is yours. You may choose to keep the baby, put the baby up for adoption or have an abortion. Nobody can take this choice away from you – not your parents, relatives, foster parents, your boyfriend and his family, the judge, or your social worker. -1- Who can I talk to If I Need Help Making A Decision About My Pregnancy? If you need information on your choices, your DCFS social worker must give you referrals for family planning counseling. -

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Related to the Definitions, Roles, and Responsibilities of Parents, Persons Acting As the Parent of a Child, and Surrogate Parents

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Related to the Definitions, Roles, and Responsibilities of Parents, Persons Acting as the Parent of a Child, and Surrogate Parents Over the years, the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and the Department of Children and Families (DCF) have frequently received questions relating to the definitions of “parent,” “person acting as the parent of a child,” and “surrogate parent.” Those definitions are of particular importance when it comes to children under the guardianship of DCF and children with disabilities. A workgroup1 was developed by the two Departments to attempt to respond to those questions which have been most frequently asked. This is not an exhaustive document and it should be noted that both Departments encourage school districts, county departments of social/human services, and tribal child welfare agencies to consult with their agency attorneys. This document does not constitute legal advice from either DCF or DPI. Definition of “Parent” Under the Children’s Code and the Juvenile Justice Code (Wisconsin Statutes): “Parent” means a biological parent, a husband who has consented to the artificial insemination of his wife under s. 891.40, or a parent by adoption. If the child is a non-marital child who is not adopted or whose parents do not subsequently intermarry under s. 767.803, “parent” includes a person acknowledged under s. 767.805 or a substantially similar law of another state or adjudicated to be the biological father. “Parent” does not include any person whose parental rights have been terminated. For purposes of the application of s. 48.028 and the federal Indian Child Welfare Act, 25 USC 1901 to 1963, “parent” means a biological parent, an Indian husband who has consented to the artificial insemination of his wife under s. -

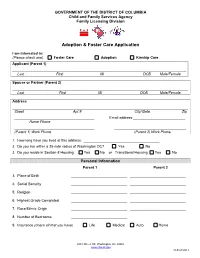

Adoption & Foster Care Application

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Child and Family Services Agency Family Licensing Division Adoption & Foster Care Application I am interested in: (Please check one) Foster Care Adoption Kinship Care Applicant (Parent 1) _______________________________________________________________________________________ Last First MI DOB Male/Female Spouse or Partner (Parent 2) ________________________________________________________________________________________ Last First MI DOB Male/Female Address ________________________________________________________________________________________ Street Apt # City/State Zip ________________________________________ Email address:__________________________ Home Phone ________________________________________ ____________________________________ (Parent 1) Work Phone (Parent 2) Work Phone 1. How long have you lived at this address: ______________________________________ 2. Do you live within a 25-mile radius of Washington DC? Yes No 3. Do you reside in Section-8 Housing: Yes No or Transitional Housing Yes No Personal Information Parent 1 Parent 2 3. Place of Birth ____________________________ ____________________________ 4. Social Security ____________________________ ____________________________ 5. Religion ____________________________ ____________________________ 6. Highest Grade Completed ____________________________ ____________________________ 7. Race/Ethnic Origin ____________________________ ____________________________ 8. Number of Bedrooms ____________________________ 9. Insurance (check all that -

Appointing a Surrogate Parent (Educational Decision-Maker) for Children with Disabilities in Foster Care

Workgroup on Improving Education For Children in Foster Care APPOINTING A SURROGATE PARENT (EDUCATIONAL DECISION-MAKER) FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN FOSTER CARE Background Children in care may not have a consistent adult to advocate for educational services and support educational goals the way a parent typically would. For children with (or suspected of having) disabilities, the need for an educational decision-maker is even more acute because federal law specifies that only certain individuals can act as a “parent” to make special education decisions. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (AIDEA@) allows Dependency Courts to determine the educational decision-maker for children under their jurisdiction with, or suspected of having, a disability. Not having a legally authorized educational Table of Contents decision-maker can hold up evaluations and appropriate special education services. Background ……………………………………………..1 One study found that the education and Why is it important to designate a “parent” to make transition plans of youth with disabilities in education decisions for children with disabilities?......2 care were lower quality than their peers, Who is a Parent under IDEA?....................................2 and youth in foster care were less likely to When Should the Court Designate an Educational Decision-Maker?........................................................2 have an advocate (family member, foster Educational Decision-maker Flowchart………………4 parent or educational surrogate) present at Who Should be Appointed as a Surrogate Parent?...5 their education planning meetings. In What are the responsibilities of a Surrogate Parent?5 addition, confusion results when the Can the school evaluate a child when there is no custodian or caseworker can sign consents parent?.......................................................................5 for school activities, but may not hold Who can Consent to School Decisions that Do Not parent status for purposes of IDEA. -

Helping Connect Children and Youth in Foster Care to Permanent Family and Relationships Through Family Finding and Engagement

Promising Approaches in Child Welfare: Helping Connect Children and Youth in Foster Care to Permanent Family and Relationships through Family Finding and Engagement September 2010 The importance of permanency for children and youth in foster care Every child and youth who enters the foster care system has a goal of finding a permanent home, also known as “permanency.” The child welfare professionals work to achieve this permanency goal by reunifying the child with their parents or finding another permanent connection, such as adoption or legal guardianship. While permanency is a goal for all children in foster care, recent statistics show a growing trend in the rising number of children “aging out” of the system without a permanent connection to a family. Over 29,000 youths aged out of foster care in 2009, and many of these foster care alumni have to face problems of poverty, lack of health care, limited education, unemployment, homelessness, criminal justice system involvement, and teen pregnancy without the support of permanent families. Outcomes for adolescents in foster care, particularly those who remain in the system and age out at age 18, are not good. These grim outcomes make older youth in foster care all too likely candidates for the Cradle to Prison Pipeline. The challenges older youth face when they age out of foster care are critical and can have harmful outcomes for those who don’t make permanent connections to family. Permanent connections can increase the likelihood that youth will achieve stability and successfully transition to independent adulthood. New reforms and efforts made through family finding can help counteract these obstacles to permanency. -

Shared Parenting

SHARED PARENTING TRAINING PARTICIPANT WORKBOOK June 2019 CHILD WELFARE SERVICES Shared Parenting Competencies and Learning Objectives Competency: Able to initiate and encourage a positive partnership between foster parents and birth parents. Objectives: 1. Can give at least two examples of the practice of the 6 principles of partnership impacting the development of shared parenting partnerships. 2. Can state two reasons for identifying common ground (connections) between foster parents and birth parents. Competency: Able to identify fears associated with Shared Parenting that create challenges to partnerships and develop strategies for dealing with these fears. Objectives: 1. Can name at least 3 fears of each partner (foster parent, birth parent and social worker) that may occur related to shared parenting. 2. Can state 2 reasons why fears impact shared parenting. 3. Can identify 3 strategies that can be utilized for helping foster parents, birth parents and social workers deal with those fears. Competency: Able to understand how partnership between foster parents and birth parents can play a role in reunification and making a permanent plan for the child. Objectives: 1. Can understand the Alliance Model and can explain the concept of partnership in the model. 2. Can name at least three boundary concerns that might be negotiated to enhance the partnership between foster parents and birth parents after reunification. 3. Can identify the steps for preparing social workers and both sets of parents for the initial shared parenting meeting. Competency: Able to apply strategies to help birth parents and foster parents work in partnership toward the best interests of the child. Objectives: 1. -

Section 3 Entering Foster Care

Virginia Department of Social Services July 2019 Child and Family Services Manual E. Foster Care 3 ENTERING FOSTER CARE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................2 3.2 Services to prevent or eliminate foster care placement ......................................... 2 3.3 The date a child is considered to enter foster care ................................................. 3 3.4 Best interests of child requirements ........................................................................ 4 3.5 Reasonable efforts requirements ............................................................................. 4 3.5.1 Initial judicial determination of reasonable efforts ....................................... 4 3.5.2 Requirements for the court order ................................................................ 5 3.5.3 Reasonable efforts after LDSS receives custody or accepts placement ...... 5 3.5.4 Reasonable efforts not required .................................................................. 5 3.5.5 When children in custody remain in their own home .................................... 6 3.6 Title IV-E funding restrictions ................................................................................... 6 3.7 Authority for placement and dispositional alternatives .......................................... 7 3.7.1 Court hearings .............................................................................................7 3.7.2 Temporary -

Out-Of-Home Placement Criteria Procedure Vi-A1

EXCERPT, POLICY VI‐A POLICY VI‐A: OUT‐OF‐HOME PLACEMENT CRITERIA 057/1109 Placement shall be chosen: A. To ensure the health and safety of a child; B. To ensure that caretakers have the skills and training sufficient to deal with the child’s special needs and any disabling condition; and C. To keep the child in close proximity to the family, if possible, to maintain enrollment in the school the child attended before placement. A minor may not be adopted or placed in a foster home if the individual seeking to adopt or to serve as a foster parent is cohabiting with a sexual partner outside of marriage which is valid under the constitution and laws of this state; additionally, there may not be any other adults in the home cohabiting with a sexual partner outside of a marriage which is valid under the constitution and laws of this state. The prohibition applies equally to cohabiting opposite‐sex and same‐sex individuals. A foster home may not house or admit any roomer or boarder. A roomer or boarder is: A. a person to whom a household furnishes lodging, meals, or both, for a reasonable monthly payment; and, B. not a household member. A household member is a resident of the home who: A. owns or is legally responsible for paying rent on the home (household head); or, B. is in a close personal relationship with a household head; or, C. is related to a household head or a to person in a close personal relationship with a household head. -

Patterns of Foster Care Placement and Family Reunification Following Child

D ECEMBER 2016 PATTERNS OF FOSTER CARE PLACEMENT AND FAMILY REUNIFICATION FOLLOWING CHILD MALTREATMENT INVESTIGATIONS Overview Some child protective services investigations result in children being placed in foster care to ensure their safety. Family reunification refers to the process of returning children to their family of origin after some time spent in foster care or another out-of-home placement. This research brief examines reunification over the course of three years following a child protective services report. The research brief identifies characteristics of children and families reunified, those who remained reunified at the end of the study, and maltreatment re-reports among children reunified with their families. This analysis is based on longitudinal survey data from the second cohort of the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW II), which is linked to administrative data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) and the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). Key Findings 1. A quarter of all children who were the subject of child maltreatment investigations in 2008 and 2009 (24.6 percent) were placed out-of-home at some point during the 3 years that followed their maltreatment report. 2. Of the children placed out-of-home, half achieved permanency within the study’s 3-year time horizon. Of those children, nearly three quarters (73.3 percent) reached permanency through reunification. 3. Among children who were reunified, 82.7 percent remained reunified at the end of the study. Approximately a quarter (24.6 percent) of reunified children were re-reported to child protective services with an allegation involving maltreatment by a family member.