Patterns of Foster Care Placement and Family Reunification Following Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Records As Sources for Social History

Case Records as Sources for Social History by G.J. PARR A decade ago the first studies of geographic and social mobility based on manuscript census returns, city directories and parish records were accorded a richly deserved welcome as the "new social history." Reviewers suggested that this quantitative work would lend healthy depth and precision to more traditionally-based inquiries into the daily life of the labouring and unlettered in the nineteenth century. ' In many ways the new history has fulfilled this prorni~e.~Our understanding of the ethnic, demographic and occupational complexion of rural and increasingly urban communities on both sides of the Atlantic has been substantially enriched. Yet this new quantitative precision has not been so successfully married with depth as had been hoped. Recent work employing more traditional mlthodology has often succeeded better in illuminating the texture of life among the "submerged" four-tenths of the last ~entury.~ With the admirable eclecticism which distinguishes the profession, historians have reached across their worktables stacked high with Among the most enduring of these earlier works are: E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: V. Gollancz, 1963); Eric Hobsbawm, Lgbouring Men (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1964) and Primitive Rebels (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959); Oscar Handlin, The Uprooted (Boston: Little, Brown, 1951); Caroline Ware, The Early New England Cotton Manufacture (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 193 1). See, for example, D.V. Glass and D.E.C. Eversley, eds., Population in History: Essays in Historical Demography (Chicago: Aldine, 1965); Peter Laslett and Richard Well, eds., Household and Family in Past Time (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972); Stephan Thernstrom, Poverty and Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth Century City (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964); Stephan Thernstrom and Richard Sennett, eds., Nineteenth Century Cities (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969). -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Permanency Practice Framework: Restoration, Adoption and Guardianship Brief Evidence Review

Permanency Practice Framework: Restoration, Adoption and Guardianship Brief Evidence Review Summary Report 4 May 2020 0 Contributing authors Dr Fiona May, Research Specialist, Parenting Research Centre Kate Spalding, Senior Implementation Specialist, Parenting Research Centre Matthew Burn, Implementation Specialist, Parenting Research Centre Catherine Murphy, Senior Implementation Specialist, Parenting Research Centre Christopher Tran, Implementation Specialist, Parenting Research Centre Warren Cann, Chief Executive Officer, Parenting Research Centre Annette Michaux, Director, Parenting Research Centre May 2020 May, F., Spalding, K., Burn, M., Murphy, C., Tran, C., Cann, W., & Michaux, A. (2020). Permanency Practice Framework: Restoration, Adoption and Guardianship Brief Evidence Review. New South Wales: Parenting Research Centre. Melbourne office Level 5, 232 Victoria Parade East Melbourne, Victoria, 3002 Australia Sydney office Suite 72, Level 7 8-24 Kippax Street Surry Hills, New South Wales, 2010 P: +61 3 8660 3500 E: [email protected] www.parentingrc.org.au Permanency Practice Framework: Restoration, Adoption and Guardianship Brief Evidence Review ii Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Summary of findings 5 2.1 Guardianship and adoption literature 5 2.2 Restoration literature 9 3. References 14 Permanency Practice Framework: Restoration, Adoption and Guardianship Brief Evidence Review iii 1. Introduction The Parenting Research Centre is working in partnership with the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) in NSW to develop an evidence-based practice framework to support practitioners in working towards the permanency goals of restoration, guardianship and adoption. The aims of this project are to: 1. Explore and analyse current practice and match against the evidence. 2. Design a practice framework which aligns with evidence-based practice for families and carers of children between 0-18 years who have been placed in out-of-home care and are moving to permanency through restoration, guardianship or adoption. -

Safety and Stability for Foster Children: a Developmental Perspective

Children, Families, and Foster Care Safety and Stability for Foster Children: A Developmental Perspective Brenda Jones Harden SUMMARY Children in foster care face a challenging jour- ders, compromised brain functioning, inade- ney through childhood. In addition to the quate social skills, and mental health difficul- troubling family circumstances that bring them ties. into state care, they face additional difficulties ◗ Providing stable and nurturing families can within the child welfare system that may further bolster the resilience of children in care and compromise their healthy development. This ameliorate negative impacts on their develop- article discusses the importance of safety and mental outcomes. stability to healthy child development and reviews the research on the risks associated with mal- The author concludes that developmentally- treatment and the foster care experience. It finds: sensitive child welfare policies and practices designed to promote the well-being of the ◗ Family stability is best viewed as a process of whole child, such as ongoing screening and caregiving practices that, when present, can assessment and coordinated systems of care, are greatly facilitate healthy child development. needed to facilitate the healthy development of ◗ Children in foster care, as a result of exposure children in foster care. to risk factors such as poverty, maltreatment, and the foster care experience, face multiple Brenda Jones Harden, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the Institute for Child Study in the Department of threats to their healthy development, includ- Human Development at the University of Maryland, ing poor physical health, attachment disor- College Park. www.futureofchildren.org 31 Jones Harden rotecting and nurturing the young is a uni- care due to their exposure to maltreatment, family versal goal across human cultures. -

Reference Guide on Protecting the Rights Of

REFERENCE GUIDE ON PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILD VICTIMS OF TRAFFICKING IN EUROPE REFERENCE GUIDE ON PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILD VICTIMS OF TRAFFICKING IN EUROPE REFERENCE GUIDE ON PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILD VICTIMS OF TRAFFICKING IN EUROPE Disclaimer: This Reference Guide has been prepared by Mike Dottridge in collaboration with the UNICEF Regional Office for CEE/CIS. Its contents do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. REFERENCE GUIDE ON PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILD VICTIMS OF TRAFFICKING IN EUROPE Foreword Today, virtually every country in Europe is facing the problem of trafficking in human beings either internally or as a country of origin, destination, transit or a combination of these. The phenomenon is not new; however, the political, social and economic changes that swept the continent in the last decade have left a specific mark on the dynamics of trafficking. Transition from centrally planned to free market economies as well as the years of war in the former Yugoslavia increased poverty and the vulnerability of women, girls and boys to exploitation including trafficking. These changes also led to an increase in corruption, lack of a rule of law and the emergence of war economies, thus enabling the trafficking industry to spread. The response of governments and of international and non-governmental organizations was swift and focused. It especially strengthened the law and law enforcement capacities to fight trafficking, and established assistance programmes for victims of trafficking. Although yielding some results, this approach was often criticized for its lack of a human rights focus. Child victims of trafficking, for example, were seldom recognised as being entitled to special protection measures. -

HELP: a Handbook for Kentucky Grandparents and Other Relative

HELP A HANDBOOK FOR KENTUCKY GRANDPARENTS AND OTHER RELATIVE CAREGIVERS ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOUNDATION LEGAL HELPLINE FOR OLDER KENTUCKIANS LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY BLUEGRASS AREA AGENCY ON AGING AND INDEPENDENT LIVING 699 PERIMETER DRIVE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40517 (859) 269-8021 This project is funded, in part, under a contract with the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, with funds from the Administration on Aging and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. HELP A HANDBOOK FOR KENTUCKY GRANDPARENTS AND OTHER RELATIVE CAREGIVERS WRITTEN BY: David Godfrey, J.D. Melanie Beckwith Jesse Reid Hodgson Jeffery Mahoney Robert Stith EDITED BY: Laura B. Grubbs Bluegrass Area Development District Bluegrass Area Agency on Aging 699 Perimeter Drive Lexington, Kentucky 40517-4120 859-269-8021 ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOUNDATION LEGAL HELPLINE FOR OLDER KENTUCKIANS Lexington, Kentucky This project is funded, in part, under a contract with the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, with funds from the Administration on Aging and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Please feel free to copy and distribute the information in this handbook for any non-commercial purpose. REVISION DATE: JANUARY 2007 EVERY EFFORT WAS MADE TO MAKE THIS DOCUMENT CURRENT THROUGH JANUARY 2007. PROGRAMS AND POLICES CHANGE, YOU SHOULD ALWAYS VERIFY THAT THE INFORMATION IS CURRENT BEFORE PROCEEDING. THE MORE TIME THAT PASSES, THE GREATER THE LIKELIHOOD THAT INFORMATION IS OUT OF DATE. ii INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Each year thousands of grandparents and other relatives in Kentucky assume the responsibility of raising children for biological parents who are unable or unwilling or to be parents. -

Teens in Foster Care and Their Babies

Teens in Foster Care and Their Babies 2013 If you are a pregnant or parenting teenager in foster care, you may have some questions or concerns. Being a teen parent can be stressful, and the added demands of the foster care system might leave you feeling confused or concerned for your baby’s future. This brochure answers some common questions and explains what your rights are as a pregnant or parenting teen in foster care. Family Planning Teens in foster care have the same right as other teens to obtain advice on birth control, family planning, and pregnancy tests without the consent of anyone else. To get these services, contact Family Planning (800) 942-1054 or Planned Parenthood (800) 576-5544. HIV Testing If you are 12 or older, you can get tested for HIV/AIDS without anyone else’s permission and without giving permission for others to be told. However, if you tell a DCFS social worker that you are HIV+ or have AIDS, the social worker must tell others. What If I Become Pregnant While I’m a Court Dependent? The decision regarding how to handle your pregnancy is yours. You may choose to keep the baby, put the baby up for adoption or have an abortion. Nobody can take this choice away from you – not your parents, relatives, foster parents, your boyfriend and his family, the judge, or your social worker. -1- Who can I talk to If I Need Help Making A Decision About My Pregnancy? If you need information on your choices, your DCFS social worker must give you referrals for family planning counseling. -

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Related to the Definitions, Roles, and Responsibilities of Parents, Persons Acting As the Parent of a Child, and Surrogate Parents

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Related to the Definitions, Roles, and Responsibilities of Parents, Persons Acting as the Parent of a Child, and Surrogate Parents Over the years, the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and the Department of Children and Families (DCF) have frequently received questions relating to the definitions of “parent,” “person acting as the parent of a child,” and “surrogate parent.” Those definitions are of particular importance when it comes to children under the guardianship of DCF and children with disabilities. A workgroup1 was developed by the two Departments to attempt to respond to those questions which have been most frequently asked. This is not an exhaustive document and it should be noted that both Departments encourage school districts, county departments of social/human services, and tribal child welfare agencies to consult with their agency attorneys. This document does not constitute legal advice from either DCF or DPI. Definition of “Parent” Under the Children’s Code and the Juvenile Justice Code (Wisconsin Statutes): “Parent” means a biological parent, a husband who has consented to the artificial insemination of his wife under s. 891.40, or a parent by adoption. If the child is a non-marital child who is not adopted or whose parents do not subsequently intermarry under s. 767.803, “parent” includes a person acknowledged under s. 767.805 or a substantially similar law of another state or adjudicated to be the biological father. “Parent” does not include any person whose parental rights have been terminated. For purposes of the application of s. 48.028 and the federal Indian Child Welfare Act, 25 USC 1901 to 1963, “parent” means a biological parent, an Indian husband who has consented to the artificial insemination of his wife under s. -

Child Labor, Exploitation and Xenophobia in the British Home Children Movement

Palma !1 “Obstinate, Impertinent, Ill-Conditioned”: Child Labor, Exploitation and Xenophobia in the British Home Children Movement A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the History Department California Polytechnic State University – San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in History By Hannah Palma 9 June, 2020 © 2020 Hannah Palma Palma !2 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Conditions in Victorian London 5 A. Need for Alternatives III. Origins of the Home Children Movement 9 A. Key Players IV. South Africa 17 V. Australia and New Zealand 19 VI. Canada 21 A. Documentation of Home Children Immigration B. Indentured Servitude vs. Adoption C. Were Home Children Truly Orphans? D. Case Study VII. Experience of Immigrant Children 26 A. Treatment B. Education C. Resulting Shame and Stigma VIII. Lengthy Timeframe of the Home Children Program 30 IX. Idealized Program vs. Reality 32 X. Conclusion 36 A. The Young English Immigrant Experience B. Patterns of Immigration in History Bibliography 40 Palma !3 Introduction The Home Children movement, in which 100,000 British children were shipped overseas to South Africa, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, lasted from 1869 until the 1970s. Proponents of the program touted the children as orphaned ‘waifs and strays’ whose last hopes for survival were open spaces and clean air beyond urban British cities. In this thesis I argue the reality of the Home Children program is much darker than how it is portrayed by its proponents and supporters, and the poor treatment of Home Children by their foster families and society as a whole is just one example in the macrohistory of immigration and anti-immigrant sentiment. -

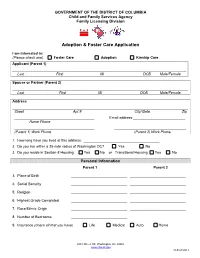

Adoption & Foster Care Application

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Child and Family Services Agency Family Licensing Division Adoption & Foster Care Application I am interested in: (Please check one) Foster Care Adoption Kinship Care Applicant (Parent 1) _______________________________________________________________________________________ Last First MI DOB Male/Female Spouse or Partner (Parent 2) ________________________________________________________________________________________ Last First MI DOB Male/Female Address ________________________________________________________________________________________ Street Apt # City/State Zip ________________________________________ Email address:__________________________ Home Phone ________________________________________ ____________________________________ (Parent 1) Work Phone (Parent 2) Work Phone 1. How long have you lived at this address: ______________________________________ 2. Do you live within a 25-mile radius of Washington DC? Yes No 3. Do you reside in Section-8 Housing: Yes No or Transitional Housing Yes No Personal Information Parent 1 Parent 2 3. Place of Birth ____________________________ ____________________________ 4. Social Security ____________________________ ____________________________ 5. Religion ____________________________ ____________________________ 6. Highest Grade Completed ____________________________ ____________________________ 7. Race/Ethnic Origin ____________________________ ____________________________ 8. Number of Bedrooms ____________________________ 9. Insurance (check all that -

Appointing a Surrogate Parent (Educational Decision-Maker) for Children with Disabilities in Foster Care

Workgroup on Improving Education For Children in Foster Care APPOINTING A SURROGATE PARENT (EDUCATIONAL DECISION-MAKER) FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN FOSTER CARE Background Children in care may not have a consistent adult to advocate for educational services and support educational goals the way a parent typically would. For children with (or suspected of having) disabilities, the need for an educational decision-maker is even more acute because federal law specifies that only certain individuals can act as a “parent” to make special education decisions. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (AIDEA@) allows Dependency Courts to determine the educational decision-maker for children under their jurisdiction with, or suspected of having, a disability. Not having a legally authorized educational Table of Contents decision-maker can hold up evaluations and appropriate special education services. Background ……………………………………………..1 One study found that the education and Why is it important to designate a “parent” to make transition plans of youth with disabilities in education decisions for children with disabilities?......2 care were lower quality than their peers, Who is a Parent under IDEA?....................................2 and youth in foster care were less likely to When Should the Court Designate an Educational Decision-Maker?........................................................2 have an advocate (family member, foster Educational Decision-maker Flowchart………………4 parent or educational surrogate) present at Who Should be Appointed as a Surrogate Parent?...5 their education planning meetings. In What are the responsibilities of a Surrogate Parent?5 addition, confusion results when the Can the school evaluate a child when there is no custodian or caseworker can sign consents parent?.......................................................................5 for school activities, but may not hold Who can Consent to School Decisions that Do Not parent status for purposes of IDEA. -

Helping Connect Children and Youth in Foster Care to Permanent Family and Relationships Through Family Finding and Engagement

Promising Approaches in Child Welfare: Helping Connect Children and Youth in Foster Care to Permanent Family and Relationships through Family Finding and Engagement September 2010 The importance of permanency for children and youth in foster care Every child and youth who enters the foster care system has a goal of finding a permanent home, also known as “permanency.” The child welfare professionals work to achieve this permanency goal by reunifying the child with their parents or finding another permanent connection, such as adoption or legal guardianship. While permanency is a goal for all children in foster care, recent statistics show a growing trend in the rising number of children “aging out” of the system without a permanent connection to a family. Over 29,000 youths aged out of foster care in 2009, and many of these foster care alumni have to face problems of poverty, lack of health care, limited education, unemployment, homelessness, criminal justice system involvement, and teen pregnancy without the support of permanent families. Outcomes for adolescents in foster care, particularly those who remain in the system and age out at age 18, are not good. These grim outcomes make older youth in foster care all too likely candidates for the Cradle to Prison Pipeline. The challenges older youth face when they age out of foster care are critical and can have harmful outcomes for those who don’t make permanent connections to family. Permanent connections can increase the likelihood that youth will achieve stability and successfully transition to independent adulthood. New reforms and efforts made through family finding can help counteract these obstacles to permanency.