From the Second Intermediate Period to the Advent of the Ramesses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.uchicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.uchicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Ebook Download a History of Ancient Egypt Ebook Free Download

A HISTORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marc Van De Mieroop | 424 pages | 30 Aug 2010 | John Wiley and Sons Ltd | 9781405160711 | English | Chicester, United Kingdom A History of Ancient Egypt PDF Book Punitive treatment of foreign slaves or of native fugitives from their obligations included forced labour , exile in, for example, the oases of the western desert , or compulsory enlistment in dangerous mining expeditions. Below the nobility were the priests, physicians, and engineers with specialized training in their field. So much of what is know of ancient Egypt is via the tombs - so it's hard to understand daily life or what wording of the day really means he uses a modern day example as "The King of Soul" The first passages which detail Egyptian pre-history, a culture and theology completely lost to us now, are fa I was disappointed that Romer is so dedicated to being a meticulous researcher and freeing himself from Victorian-imposed preconceptions, that there is almost no interpretation about the lives and everyday structure of Egyptian society, focusing instead on the mechanics of pyramid building. This means that some areas that are now barren desert were fertile. Romer dismisses this out of hand, pointing out that no archaeological evidence of military conquest from that time has been found. Abydos Dynasty. I may come back and read it again once I have and my review may change Neolithic late Stone Age communities in northeastern Africa exchanged hunting for agriculture and made early advances that paved the way for the later development of Egyptian arts and crafts, technology, politics and religion including a great reverence for the dead and possibly a belief in life after death. -

A Comparison of the Polychrome Geometric Patterns Painted on Egyptian “Palace Façades” / False Doors with Potential Counterparts in Mesopotamia

A comparison of the polychrome geometric patterns painted on Egyptian “palace façades” / false doors with potential counterparts in Mesopotamia Lloyd D. Graham Abstract: In 1st Dynasty Egypt (ca. 3000 BCE), mudbrick architecture may have been influenced by existing Mesopotamian practices such as the complex niching of monumental façades. From the 1st to 3rd Dynasties, the niches of some mudbrick mastabas at Saqqara were painted with brightly-coloured geometric designs in a clear imitation of woven reed matting. The possibility that this too might have drawn inspiration from Mesopotamian precedents is raised by the observation of similar geometric frescoes at the Painted Temple in Tell Uqair near Baghdad, a Late Uruk structure (ca. 3400-3100 BCE) that predates the proposed timing of Mesopotamian influence on Egyptian architecture (Jemdet Nasr, ca. 3100-2900 BCE). However, detailed scrutiny favours the idea that the Egyptian polychrome panels were an indigenous development. Panels mimicking reed mats, animal skins and wooden lattices probably proved popular on royal and religious mudbrick façades in Early Dynastic Egypt because they emulated archaic indigenous “woven” shelters such as the per-nu and per-wer shrines. As with Mesopotamian cone mosaics – another labour-intensive technique that seems to have mimicked textile patterns – the scope of such panels became limited over time to focal points in the architecture. In Egyptian tombs, the adornment of key walls and funerary equipment with colourful and complex geometric false door / palace façade composites (Prunkscheintüren) continued at least into the Middle Kingdom, and the template persisted in memorial temple decoration until at least the late New Kingdom. -

Clarity Chronology: Egypt's Chronology in Sync with the Holy Bible Eve Clarity, P1

Clarity Chronology: Egypt's chronology in sync with the Holy Bible Eve Clarity, p1 Clarity Chronology This Egyptian chronology is based upon the historically accurate facts in the Holy Bible which are supported by archaeological evidence and challenge many assumptions. A major breakthrough was recognizing Joseph and Moses lived during the reigns of several pharaohs, not just one. During the 18th dynasty in which Joseph and Moses lived, the average reign was about 15 years; and Joseph lived 110 years and Moses lived 120 years. The last third of Moses' life was during the 19th dynasty. Though Rameses II had a reign of 66 years, the average reign of the other pharaohs was only seven years. Biblical chronology is superior to traditional Egyptian chronology Joseph was born in 1745 BC during the reign of Tao II. Joseph was 17 when he was sold into slavery (1728 BC), which was during the reign of Ahmose I, for the historically accurate amount of 20 pieces of silver.1 Moses (1571-1451 BC) was born 250 years after the death of the Hebrew patriarch, Abraham. Moses lived in Egypt and wrote extensively about his conversations and interactions with the pharaoh of the Hebrews' exodus from Egypt; thus providing a primary source. The history of the Hebrews continued to be written by contemporaries for the next thousand years. These books (scrolls) were accurately copied and widely disseminated. The Dead Sea Scrolls contained 2,000 year old copies of every book of the Bible, except Esther, and the high accuracy of these copies to today's copies in original languages is truly astonishing. -

In the Shadow of Osiris: Non-Royal Mortuary Landscapes at South

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2014 In the Shadow of Osiris: Non-Royal Mortuary Landscapes at South Abydos During the Late Middle and New Kingdoms Kevin Michael Cahail University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Islamic World and Near East History Commons Recommended Citation Cahail, Kevin Michael, "In the Shadow of Osiris: Non-Royal Mortuary Landscapes at South Abydos During the Late Middle and New Kingdoms" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1222. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1222 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1222 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In the Shadow of Osiris: Non-Royal Mortuary Landscapes at South Abydos During the Late Middle and New Kingdoms Abstract Kevin M. Cahail Dr. Josef W. Wegner The site of South Abydos was home to royal mortuary complexes of both the late Middle, and New Kingdoms, belonging to Senwosret III and Ahmose. Thanks to both recent and past excavations, both of these royal establishments are fairly well understood. Yet, we lack a clear picture of the mortuary practices of the non- royal individuals living and working in the shadow of these institutions. For both periods, the main question is where the tombs of the non-royal citizens might exist. Additionally for the Middle Kingdom is the related issue of how these people commemorated their dead ancestors. Divided into two parts, this dissertation looks at the ways in which non-royal individuals living at South Abydos during these two periods dealt with burial and funerary commemoration. -

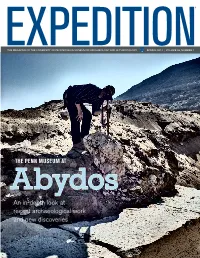

An In-Depth Look at Recent Archaeological Work and New Discoveries “…Everything Has a Past

® EXPEDITIONTHE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY SPRING 2014 | VOLUME 56, NUMBER 1 THE PENN MUSEUM AT Abydos An in-depth look at recent archaeological work and new discoveries “…everything has a past. Everything – a person, an object, a word, everything. If you don’t know the past, you can’t understand the present and plan properly for the future.” — !"#$% &'('), *#+$(#’, "#-& RIGHT: This New Kingdom statue (1479-1458 BCE) depicts the overseer of priests, Sitepehu. The form of his body is only faintly perceptible beneath his long robe that completely covers his body and feet. The statue is notable for its large size and unusually well-preserved paint. The inscription on the front and right side of the statue addresses requests for the afterlife to the gods Osiris and Inheret, and lists Sitepehu’s name, titles, epithets and virtues. PLAN FOR WHAT’S IMPORTANT TO YOU Today’s interest rates create a favorable climate for Charitable Lead Trusts, which allow some donors to: • leverage significant gift and estate tax advantages, enabling transfers to heirs at a lower tax cost • distribute appreciated trust assets to heirs without additional tax • smooth out income if created during an unusually high-income year Please contact Robert Vosburgh at [email protected] or 215.573.5251 to learn more about creative and advantageous ways to support the Penn Museum. SPRING 2014 | VOLUME 56, NUMBER 1 NEW DISCOVERIES 39 Discovering Pharaohs Sobekhotep & contents Senebkay: An Update from the 2013–2014 Field -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Ucicago.Edu

oi.ucicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.ucicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.ucicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.ucicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.ucicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

1. the 14Th Dynasty Only Ruled Lower Egypt (Northern Egypt)

1. The 14th Dynasty only ruled Lower Egypt (Northern Egypt). Upper Egypt or Southern Egypt had its own dynasties at the time. The 13th dynasty ruled Upper Egypt concurrently with the 14th dynasty in Egypt. The 14th dynasty was established by waves of immigrants from the levant. The 12th Dynasty of Egypt came to an end at the end of the 19th century BC with the death of Queen Sobekneferu (1806–1802 BC). Apparently she had no heirs, causing the 12th dynasty to come to a sudden end, and, with it, the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom; it was succeeded by the much weaker 13th Dynasty. Retaining the seat of the 12th dynasty, the 13th dynasty ruled from Itjtawy ("Seizer-of-the-Two-Lands") near Memphis and Lisht, just south of the apex of the Nile Delta. The 13th dynasty is notable for the accession of the first formally recognised Semitic-speaking king, Khendjer ("Boar"). The 13th Dynasty proved unable to hold on to the entire territory of Egypt however, and a provincial ruling family of Western Asian descent in Avaris, located in the marshes of the eastern Nile Delta, broke away from the central authority to form the 14th Dynasty. The first kings of the 14th Dynasty appear to have had fairly long and prosperous reigns. Despite their foreign origins, they adopted the traditional royal titulary, and included the name of the Egyptian solar god Re into their own throne names. This dynasty also seems to have had very good relationships with Nubia and at least one of its kings, Sheshi, may have been married to a Nubian princess. -

Abydos: the Sacred

Colloquium abstracts Abydos: the sacred land at the western horizon Thursday 9 July & Friday 10 July 2015 The origins of sacredness at Abydos extensive evidence of use from the First Matthew D Adams, Institute of Fine Arts, Intermediate Period through the Late Roman New York University Period. Destroyed to its lowest courses, as all the Fieldwork in recent years has shed substantial new First Dynasty funerary enclosures were, there is light on how Egypt’s early kings used the dramatic nonetheless reason to ask if and how the memory desert landscape of north Abydos as an arena for of this effectively invisible monument affected later royal display and performance. The same kings of decisions about sacred space in the North Dynasties 1 and 2 who built tombs for themselves Cemetery. This talk will examine the dense at Umm el-Qa‛ab built corresponding highly visible palimpsest of usage over a 4,000-year span in a monumental walled ritual precincts on the northern very small area from the perspectives of visibility, desert terrace overlooking the ancient town. invisibility, and the selective reverence for earlier Although the later reinterpretation of the area of the monuments shown by later users of the site. royal tombs has received considerable scholarly attention, I would argue that the singular use of the Umm el-Qaʽab and the sacred landscape of desert landscape of north Abydos by these early Abydos: new perspectives based on the kings and the material remains left embedded in it votive pottery for Osiris also represent fundamental aspects of the Julia Budka, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität phenomena that imbued the site with a unique München significance in Egyptian culture, one that came to The landscape of Abydos took active part in be expressed through both applied mythic meaning forming the importance of the site as burial place and later ritual practice. -

The King's Chief Librarian and Guardian of the Royal Archives Of

Archaeological Discovery, 2017, 5, 163-177 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ad ISSN Online: 2331-1967 ISSN Print: 2331-1959 A New Interpretation of a Rare Old Kingdom Dual Title: The King’s Chief Librarian and Guardian of the Royal Archives of Mehit Manu Seyfzadeh1, Robert M. Schoch2, Robert Bauval3 1Independent Researcher, Lake Forest, USA 2Institute for the Study of the Origins of Civilization, College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, USA 3Independent Researcher, Málaga, Spain How to cite this paper: Seyfzadeh, M., Abstract Schoch, R. M., & Bauval, R. (2017). A New Interpretation of a Rare Old Kingdom Dual To date, no unequivocal textual reference to the Great Sphinx has been identi- Title: The King’s Chief Librarian and fied prior to Egypt’s New Kingdom. Here, we present evidence that the Guardian of the Royal Archives of Mehit. monument we now know as the Great Sphinx was called Mehit and that this Archaeological Discovery, 5, 163-177. name was part of an exclusive title held only by the highest officials of the https://doi.org/10.4236/ad.2017.53010 royal Egyptian court going back to at least early dynastic times, i.e. prior to th Received: June 22, 2017 the time of the Great Sphinx’s generally presumed construction during the 4 Accepted: July 18, 2017 Dynasty. Furthermore, the symbolic origins of this title precede the 4th Dy- Published: July 21, 2017 nasty by at least five centuries, going back to the very cradle of writing during Copyright © 2017 by authors and the earliest dynastic era of the early Nile civilization.