Appendices MISQ Archivist for Business Process Change: a Study of Methodologies, Techniques and Tools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAKING DATA MODELS READABLE David C

MAKING DATA MODELS READABLE David C. Hay Essential Strategies, Inc. “Confusion and clutter are failures of [drawing] design, not attributes of information. And so the point is to find design strategies that reveal detail and complexity ¾ rather than to fault the data for an excess of complication. Or, worse, to fault viewers for a lack of understanding.” ¾ Edward R. Tufte1 Entity/relationship models (or simply “data models”) are powerful tools for analyzing and representing the structure of an organization. Properly used, they can reveal subtle relationships between elements of a business. They can also form the basis for robust and reliable data base design. Data models have gotten a bad reputation in recent years, however, as many people have found them to be more trouble to produce and less beneficial than promised. Discouraged, people have gone on to other approaches to developing systems ¾ often abandoning modeling altogether, in favor of simply starting with system design. Requirements analysis remains important, however, if systems are ultimately to do something useful for the company. And modeling ¾ especially data modeling ¾ is an essential component of requirements analysis. It is important, therefore, to try to understand why data models have been getting such a “bad rap”. Your author believes, along with Tufte, that the fault lies in the way most people design the models, not in the underlying complexity of what is being represented. An entity/relationship model has two primary objectives: First it represents the analyst’s public understanding of an enterprise, so that the ultimate consumer of a prospective computer system can be sure that the analyst got it right. -

Value Mapping – Critical Business Architecture Viewpoint

Download this and other resources @ http://www.aprocessgroup.com/myapg Value Mapping – Critical Business Architecture Viewpoint AEA Webinar Series “Enterprise Business Intelligence” Armstrong Process Group, Inc. www.aprocessgroup.com Copyright © 1998-2017, Armstrong Process Group, Inc., All rights reserved 2 About APG APG’s mission is to “Align information technology and systems engineering capabilities with business strategy using proven, practical processes delivering world-class results.” Industry thought leader in enterprise architecture, business modeling, process improvement, systems and software engineering, requirements management, and agile methods Member and contributor to UML ®, SysML ®, SPEM, UPDM ™ at the Object Management Group ® (OMG ®) TOGAF ®, ArchiMate ®, and IT4IT ™ at The Open Group BIZBOK ® Guide and UML Profile at the Business Architecture Guild Business partners with Sparx, HPE, and IBM Guild Accredited Training Partner ™ (GATP ™) and IIBA ® Endorsed Education Provider (EEP ™) AEA Webinar Series – “Enterprise Business Intelligence” – Value Mapping Copyright © 1998-2017, Armstrong Process Group, Inc., All rights reserved 3 Business Architecture Framework Business Architecture Knowledgebase Blueprints provide views into knowledgebase, based on stakeholder concerns Scenarios contextualize expected outcomes of business architecture work Also inform initial selections of key stakeholders and likely concerns AEA Webinar Series – “Enterprise Business Intelligence” – Value Mapping BIZBOK Guide Copyright © 1998-2017, -

Modelling, Analysis and Design of Computer Integrated Manueactur1ng Systems

MODELLING, ANALYSIS AND DESIGN OF COMPUTER INTEGRATED MANUEACTUR1NG SYSTEMS Volume I of II ABDULRAHMAN MUSLLABAB ABDULLAH AL-AILMARJ October-1998 A thesis submitted for the DEGREE OP DOCTOR OF.PHILOSOPHY MECHANICAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT, THE UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD 3n ti]S 5íamc of Allai]. ¿Hoot (gractouo. iHHoßt ¿Merciful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation and thanks to my supervisor Professor Keith Ridgway for devoting freely of his time to read, discuss, and guide this research, and for his assistance in selecting the research topic, obtaining special reference materials, and contacting industrial collaborations. His advice has been much appreciated and I am very grateful. I would like to thank Mr Bruce Lake at Brook Hansen Motors who has patiently answered my questions during the case study. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their constant understanding, support and patience. l To my parents, my wife and my son. ABSTRACT In the present climate of global competition, manufacturing organisations consider and seek strategies, means and tools to assist them to stay competitive. Computer Integrated Manufacturing (CIM) offers a number of potential opportunities for improving manufacturing systems. However, a number of researchers have reported the difficulties which arise during the analysis, design and implementation of CIM due to a lack of effective modelling methodologies and techniques and the complexity of the systems. The work reported in this thesis is related to the development of an integrated modelling method to support the analysis and design of advanced manufacturing systems. A survey of various modelling methods and techniques is carried out. The methods SSADM, IDEFO, IDEF1X, IDEF3, IDEF4, OOM, SADT, GRAI, PN, 10A MERISE, GIM and SIMULATION are reviewed. -

CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY of AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODS and PROJECT PERFORMANCE Tracy Lambert Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and HCBE Theses and Dissertations Entrepreneurship 2011 CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY OF AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODS AND PROJECT PERFORMANCE Tracy Lambert Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hsbe_etd Part of the Business Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Tracy Lambert. 2011. CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY OF AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODS AND PROJECT PERFORMANCE. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneurship. (56) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hsbe_etd/56. This Dissertation is brought to you by the H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCBE Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY OF AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODS AND PROJECT PERFORMANCE By Tracy Lambert A DISSERTATION Submitted to H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneurship Nova Southeastern University in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of DOCTOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 2011 ABSTRACT CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY OF AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT METHODS AND PROJECT PERFORMANCE by Tracy Lambert Agile software development methods, characterized by delivering customer value via incremental and iterative time-boxed development processes, have moved into the mainstream of the Information Technology (IT) industry. -

H)EF3 Technical Report Version 1.0 Chard J. Mayer Christopher P

L. H)EF3 Technical Report Version 1.0 _| i L, _chard J. Mayer Christopher P. Menzel : i_:_pa_la S.D. Mayer Know!edge Based Systems Laboratory L Depar tment- 0 fin-dustrial Engineering Texas A&M University College Station TX 77843 Reviewed by Michad-K, Painter, Capt, USAF Armstrong Laboratory Logistics Research Division Wright-Patterson =Air Force Base, Ohio 45433-6503 :_ _=_January 1991 i _: ?_ | - , i (NASA-CR-I90279) {RESEARCH ACCOMPLISHED AT N92-26587 THE KNOWLEDGE BASED SYSTEMS LAB: IDEF3, VERSION 1.0] (Texas A&M Univ.) 56 p Unclag G]/_I 0086873 L == ; IDEF3 Technical Report Version 1.0 Richard J. Mayer Christopher P. Menzel Paula S.D. Mayer Knowledge Based Systems Laboratory Department of Industrial Engineering Texas A&M University College Station TX 77843 Reviewed by Michael K. Painter, Capt, USAF Armstrong Laboratory Logistics Research Division Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio 45433-6503 January 1991 umd w _- :7. m w Preface This paper describes the research accomplished at the Knowledge Based Systems Laboratory of the Department of Industrial Engineering at Texas A&M University. Funding for the Laboratory's research in Integrated Information System Development Methods and Tools has been provided by the Air Force Armstrong Laboratory, Logistics Research Division, AFWAL/LRL, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio 45433, under the technical direction of USAF Captain Michael K. Painter, under subcontract through the NASA RICIS Program at the University of Houston. The authors and the design team wish to acknowledge the technical insights and ideas provided by Captain Painter in the performance of this research as well as his assistance in the preparation of this report. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

Just Enough Structured Analysis Chapter 1: Introduction “The beginnings and endings of all human undertakings are untidy, the building of a house, the writing of a novel, the demolition of a bridge, and, eminently, the finish of a voyage.” — John Galsworthy Over the River, 1933 www.yourdon.com ©2006 Ed Yourdon - rev. 051406 In this chapter, you will learn: 1. Why systems analysis is interesting; 2. Why systems analysis is more difficult than programming; and 3. Why it is important to be familiar with systems analysis. Chances are that you groaned when you first picked up this book, seeing how heavy and thick it was. The prospect of reading such a long, technical book is enough to make anyone gloomy; fortunately, just as long journeys take place one day at a time, and ultimately one step at a time, so long books get read one chapter at a time, and ultimately one sentence at a time. 1.1 Why is systems analysis interesting? Long books are often dull; fortunately, the subject matter of this book — systems analysis — is interesting. In fact, systems analysis is more interesting than anything I know, with the possible exception of sex and some rare vintages of Australian wine. Without a doubt, it is more interesting than computer programming (not that programming is dull) because it involves studying the interactions of people, and disparate groups of people, and computers and organizations. As Tom DeMarco said in his delightful book, Structured Analysis and Systems Specification (DeMarco, 1978), [systems] analysis is frustrating, full of complex interpersonal relationships, indefinite, and difficult. -

Edward Yourdon

EDWARD YOURDON EDWARD YOURDON is an internationally-recognized computer consultant, as well as the author of more than two dozen books, including Byte Wars, Managing High-Intensity Internet Projects, Death March, Rise and Resurrection of the American Programmer, and Decline and Fall of the American Programmer. His latest book, Outsource: competing in the global productivity race, discusses both current and future trends in offshore outsourcing, and provides practical strategies for individuals, small businesses, and the nation to cope with this unstoppable tidal wave. According to the December 1999 issue of Crosstalk: The Journal of Defense Software Engineering, Ed Yourdon is one of the ten most influential men and women in the software field. In June 1997, he was inducted into the Computer Hall of Fame, along with such notables as Charles Babbage, Seymour Cray, James Martin, Grace Hopper, Gerald Weinberg, and Bill Gates. Ed is widely known as the lead developer of the structured analysis/design methods of the 1970s, as well as a co-developer of the Yourdon/Whitehead method of object-oriented analysis/design and the Coad/Yourdon OO methodology in the late 1980s and 1990s. He was awarded a Certificate of Merit by the Second International Workshop on Computer-Aided Software Engineering in 1988, for his contributions to the promotion of Structured Methods for the improvement of Information Systems Development, leading to the CASE field. He was selected as an Honored Member of Who’s Who in the Computer Industry in 1989. And he was given the Productivity Award in 1992 by Computer Language magazine, for his book Decline and Fall of the American Programmer. -

A Brief History of Devops by Alek Sharma Introduction: History in Progress

A Brief History of DevOps by Alek Sharma Introduction: History in Progress Software engineers spend most of their waking hours wading George Santayana wrote that “those who cannot remember the through the mud of their predecessors. Only a few are lucky past are condemned to repeat it.” He was definitely not thinking enough to see green fields before conflict transforms the about software when he wrote this, but he’s dead now, which terrain; the rest are shipped to the front (end). There, they means he can be quoted out of context. Oh, the joys of public languish in trenches as shells of outages explode around them. domain! Progress is usually glacial, though ground can be covered This ebook will be about the history of software development through heroic sprints. methodologies — especially where they intersect with traditional best practices. Think of it as The Silmarillion of Silicon Valley, But veterans do emerge, scarred and battle-hardened. They except shorter and with more pictures. Before plunging into this revel in relating their most daring exploits and bug fixes to new rushing river of time, please note that the presented chronology recruits. And just as individuals have learned individual lessons is both theoretically complete and practically in progress. In other about writing code, our industry has learned collective lessons words, even though a term or process might have been coined, it about software development at scale. It’s not always easy to always takes more time for Best Practices to trickle down to Real see these larger trends when you’re on the ground — buried in Products. -

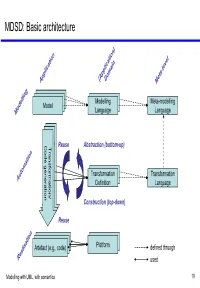

MDSD: Basic Architecture

MDSD: Basic architecture Model Modelling Meta-modelling ModelModel Model Language Language Codegeneration Transformation/ Codegeneration Transformation/ Code generation Transformation/ Reuse Abstraction (bottom-up) TransformationModel Transformation Definition Language Construction (top-down) Reuse Model Model Artefact Model(e.g., code) Platform defined through used Modelling with UML, with semantics 19 MDSD: A bird’s view Implementation Model Transformer J2EE Implementation .Net Transformation Knowledge Implementation . Modelling with UML, with semantics 20 How is MDSD realised? • Developer develops model(s), Model ModelModel Meta-model expressed using a DSL, based on certain meta-model(s). Transformation Using code generation templates, the Transformer • Rules model is transformed into executable code. • Alternative: Interpretation Model Meta-model optional, can be repeated • Optionally, the generated code is merged with manually written code. Code Transformer Generation Templates • One or more model-to-model transformation steps may precede code generation. Manually Generated Code Written Code optional Modelling with UML, with semantics 21 (Meta-)Model hierarchy conformsTo Meta-meta-model meta Meta-meta-model MOF element M3 meta conformsTo Meta-model element Relational UML … meta-model meta-model M2 Meta-model meta conformsTo repOf Model element System … … M1 Model Modelling with UML, with semantics 22 (Meta-)Model hierarchy: Example conformsTo MOF Meta-meta-model source Association destination Class conformsTo Relational Meta-model -

Product Realization Process Modeling

NAT’L INST. OF STAND & .TECH R I.C III! Ill" I" 'I mill mill II ml II II AlllDM NISTIR 5745 Product Realization Process Modeling: A study of requirements, methods and and research issues Kevin W. Lyons U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Michael R. Duffey Richard C. Anderson George Washington University QC 100 NIST .056 NO. 5745 1995 Product Realization Process Modeling: A study of requirements, methods and and research issues Kevin W. Lyons U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Michael R. Duffey Richard C. Anderson George Washington University June 1995 c U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronald H. Brown, Secretary TECHNOLOGY ADMINISTRATION Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Technology NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Arati Prabhakar, Director . r•^ - . 'it'/ ' ' ' ' - ' ' -•*'1 X' . r • ^.,' v./f/v ’• '^^,. • T,?. - ^ •' V.y' ’ ' :AIa ' / ><- l> r / PRP Modeling: Page 2 1. Introduction 7 2. Definition of a PRP Model 8 3. Overview of PRP Methods and Modeling Issues in Manufacturing Industries 9 3.1 PERT-based Models 9 3.2 IDEF-based Models 10 3.3 Traditional PRP Modeling Practices 12 3.4 Emerging PRP Model Applications in Industry 14 3.5 Industry Requirements for PRP Models 14 4. Modeling Issues for Advanced PRP Computer Tools 16 4. 1 Activity Network Representations 17 4.2 Representing Design Iteration and Activity "Overlapping" 18 4.3 Uncertainty Modeling of a PRP 20 4.3.1 Some Simulation Considerations 20 4.3.2 Activity Duration Uncertainty 21 4.3.3 Concurrent Activities and Stochastic Modeling 22 4.3.4 Alternative Representations of Uncertainty 23 4.4 Representing Economic Information 24 4.5 Data Collection and Validation Issues for PRP Models 27 4.6 Knowledge-Based Representations in PRP Models 28 5. -

Multi-Level Modeling of Complex Socio-Technical Systems Report No

Multi-Level Modeling of Complex Socio-Technical Systems Report No. CCSE-2013-01 Dr. William B. Rouse, Stevens Institute of Technology Dr. Douglas A. Bodner, Georgia Institute of Technology Report No. CCSE-2013-01 June 11, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Stevens Institute of Technology, Systems Engineering Research Center This material is baseD upon work supporteD, in whole or in part, by the U.S. Department of Defense through the Systems Engineering Research Center (SERC) unDer Contract H98230-08-D-0171. SERC is a feDerally funDeD University AffiliateD Research Center manageD by Stevens Institute of Technology The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments anD suggestions of John Casti anD HarolD Sorenson Any opinions, finDings anD conclusions or recommenDations expresseD in this material are those of the author(s) anD Do not necessarily reflect the views of the UniteD States Department of Defense. NO WARRANTY THIS STEVENS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS ENGINEERING RESEARCH CENTER MATERIAL IS FURNISHED ON AN “AS-IS” BASIS. STEVENS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MAKES NO WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, AS TO ANY MATTER INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTY OF FITNESS FOR PURPOSE OR MERCHANTABILITY, EXCLUSIVITY, OR RESULTS OBTAINED FROM USE OF THE MATERIAL. STEVENS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY DOES NOT MAKE ANY WARRANTY OF ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO FREEDOM FROM PATENT, TRADEMARK, OR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT. Center for Complex Systems & Enterprises Report No. CCSE-2013-01 June 11, 2013 2 ABSTRACT This report presents a conceptual framework for multi-level moDeling of complex socio- technical systems, proviDes linkages to the historical roots anD technical unDerpinnings of this framework, anD outlines a catalog of component moDels for populating multi-level moDels. -

IDEF Methods for BPR to Support CALS

IDEF Methods for BPR to Support CALS Comprehensive Solutions for a Complex World IDEF and CALS • CALS technologies enable paperless environments or the electronic flow of information. •The implementation of CALS technologies require a re-engineering of enterprises. IDEF and BPR • Business Process Reengineering (BPR) assists in re-engineering the enterprises and the successful implementation of CALS. • IDEF Methods support BPR activities (e.g., knowledge acquisition, As-Is analysis, To -Be design, project planning, and implementation). What are Methods? Methods: A structured approach to capturing knowledge that maximizes accuracy but is also flexible enough to capture the real-world characteristics of that knowledge. What are IDEF Methods? Integration DEFinition methods Knowledge Acquisition, Analysis, and Design tools Languages that include both graphics (diagrams) and text Formal procedures for constructing models or ditifdescriptions of a parti tilcular aspect tf of an organization Why IDEF? IDEF: The IDEF Family of Methods was co- developed by industry and government. Their pppurpose is to provide a com prehensive yet flexible framework for describing, analyzing, and evaluatinggp business practices. The y are not proprietary and are supported by international standards. Characteristics of an IDEF Method Designed to address specific aspects of a problem, or provide different perspectives of the same problem Provide an explicit mechanism for integrating the results of the application of one IDEF with another Embody the knowledge