2018 Maryland Oyster Restoration Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S. Department of the Interior Maryland-Delaware-D.C. District [email protected] U.S. Geological Survey 8987 Yellow Brick Road http://md.water.usgs.gov/ Baltimore, MD 21237 Release: Contact: Phone: Fax: January 4, 2002 Wendy S. McPherson (410) 238-4255 (410) 238-4210 Below Normal Rainfall and Warm Temperatures Lead to Record Low Water Levels in December Three months of above normal temperatures and four months of below normal rainfall have led to record low monthly streamflow and ground-water levels, according to hydrologists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Baltimore, Maryland. Streamflow was below normal at 94 percent of the real-time USGS gaging stations and 83 percent of the USGS observation wells across Maryland and Delaware in December. Record low streamflow levels for December were set at Winters Run and Pocomoke River. Streamflow levels at Deer Creek and Winters Run in Harford County have frequently set new record daily lows for the last four months (see real-time graphs at http://md.water.usgs.gov/realtime/). Streamflow was also significantly below normal at Antietam Creek, Choptank River, Conococheague Creek, Nassawango Creek, Patapsco River, Gunpowder River, Patuxent River, Piscataway Creek, Monocacy River, and Potomac River in Maryland, and Christina River, St. Jones River, and White Clay Creek in Delaware. The monthly streamflow in the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. was 82 percent below normal in December and 54 percent below normal for 2001. Streamflow entering the Chesapeake Bay averaged 23.7 bgd (billion gallons per day), which is 54 percent below the long-term average for December. -

Nautical Information for Skippers and Crews

Sail Plan Pentagon Sailing Club 2016 Memorial Day Raftup: “STORM FRONT COMING” 2830 May 2016 Nautical Information for Skippers and Crews FLOAT PLAN ******************************************************************************************** References: NOAA Charts 12270 Chesapeake Bay – Chesapeake Eastern Bay and South River; 1:40,000 12266 Chesapeake Bay – Chesapeake – Choptank and Herring Bay; 1:40,000 12280 Chesapeake Bay – 1:200,000 Pentagon Sailing Club RaftUp Guidelines (revised 06/2005; link online at the PSC site under “RaftUp”) Saturday, 28 May 16. Sail from Annapolis, MD the Chesapeake Bay to Trippe Creek, vicinity of Choptank River. Raft up Saturday night (see Navigation below). Distance from Annapolis (direct route past Thomas Point to Choptank River, Tred Avon River, then Trippe Creek and raft up location) is approximately 33 nm Sunday, 29 May 16. Exit Trippe Creek, Tred Avon River, then Choptank River to Campbell’s Boatyard LLC, Bachelor’s Point Marina (Oxford, MD). Dinner will be held at “The Masthead at Pier Street Marina” restaurant in Oxford, MD; cocktails from 5pm, and dinner from 6 to 8pm. Monday, 30 May 16. Sail back to respective points of origin NAVIGATION ******************************************************************************************** Saturday, 28 May: Sail from Annapolis, MD to Raft up destination is in the Trippe Creek vic 038º 42.8 North; 076º 07.3 West. See Chart A and B. From Annapolis R “2” Fl R 2.5s (Lat 038º 56.4 N; Lon 076º 25.3 W) Sail from R “2” Fl R 2.5s 185º M to WP A (Lat 038º -

MARK-RECAPTURE ASSESSMENT of the RECREATIONAL BLUE CRAB (Callinectes Sapidus) HARVEST in CHESAPEAKE BAY, MARYLAND

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: MARK-RECAPTURE ASSESSMENT OF THE RECREATIONAL BLUE CRAB (Callinectes sapidus) HARVEST IN CHESAPEAKE BAY, MARYLAND Robert Francis Semmler, Master of Science, 2016 Directed By: Professor, Marjorie Reaka, Marine Estuarine Environmental Science In Maryland, commercial blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) harvests are monitored through mandatory, annual harvest reporting, but no annual monitoring exists for recreational fishers. This study used a large-scale mark-recapture program to assess relative exploitation between the recreational and commercial fishing sectors in 15 harvest reporting areas of Maryland, then incorporated movement information and extrapolated reported commercial harvest data to generate statewide estimates of recreational harvest. Results indicate spatial variation in recreational fishing, with a majority of recreational harvests coming from tributaries of the Western Shore and the Wye and Miles Rivers on the Eastern Shore. Statewide, recreational harvest has remained approximately 8% as large as commercial harvest despite management changes in 2008, and remains a larger proportion (12.8%) of male commercial harvest. In addition, this study provides detailed spatial information on recreational harvest and the first information on rates of exchange of male crabs among harvest reporting areas. MARK-RECAPTURE ASSESSMENT OF THE RECREATIONAL BLUE CRAB (Callinectes sapidus) HARVEST IN CHESAPEAKE BAY, MARYLAND By Robert Francis Semmler Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, 2016 Advisory Committee: Professor Anson H. Hines, Co-Chair Professor Marjorie L. Reaka, Co-Chair Professor Elizabeth W. North Dr. Matthew B. Ogburn © Copyright by Robert Francis Semmler 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. -

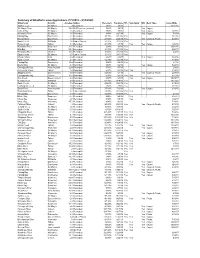

Summary of Lease Applications 9-23-20.Xlsx

Summary of Shellfish Lease Applications (1/1/2015 - 9/23/2020) Waterbody County AcreageStatus Received CompleteTFL Sanctuary WC Gear Type IssuedDate Smith Creek St. Mary's 3 Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 11/21/16 St. Marys River St. Mary's 16.2 GISRescreen (revised) 1/6/15 1/6/15 Yes Cages Calvert Bay St. Mary's 2.5Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 YesCages 2/28/17 Wicomico River St. Mary's 4.5Recorded 1/8/15 1/27/15 YesCages 5/8/19 Fishing Bay Dorchester 6.1 Recorded 1/12/15 1/12/15 Yes 11/2/15 Honga River Dorchester 14Recorded 2/10/15 2/26/15Yes YesCages & Floats 6/27/18 Smith Creek St Mary's 2.6 Under Protest 2/12/15 2/12/15 Yes Harris Creek Talbot 4.1Recorded 2/19/15 4/7/15 Yes YesCages 4/28/16 Wicomico River Somerset 26.7Recorded 3/3/15 3/3/15Yes 10/20/16 Ellis Bay Wicomico 69.9Recorded 3/19/15 3/19/15Yes 9/20/17 Wicomico River Charles 13.8Recorded 3/30/15 3/30/15Yes 2/4/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 1.7 Under Protest 3/31/15 3/31/15 Yes Chester River Kent 4.9Recorded 4/6/15 4/9/15 YesCages 8/23/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 2.1 Recorded 4/23/15 4/23/15 Yes 9/19/16 Fishing Bay Dorchester 12.4Recorded 5/4/15 6/4/15Yes 6/1/16 Breton Bay St. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1946, Volume 41, Issue No. 4

MHRYMnD CWAQAZIU^j MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE DECEMBER • 1946 t. IN 1900 Hutzler Brothers Co. annexed the building at 210 N. Howard Street. Most of the additional space was used for the expansion of existing de- partments, but a new shoe shop was installed on the third floor. It is interesting to note that the shoe department has now returned to its original location ... in a greatly expanded form. HUTZLER BPOTHERSe N\S/Vsc5S8M-lW MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE A Quarterly Volume XLI DECEMBER, 1946 Number 4 BALTIMORE AND THE CRISIS OF 1861 Introduction by CHARLES MCHENRY HOWARD » HE following letters, copies of letters, and other documents are from the papers of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (b. 1805, d. 1888). They are confined to a brief period of great excitement in Baltimore, viz, after the riot of April 19, 1861, when Federal troops were attacked by the mob while being marched through the City streets, up to May 13th of that year, when General Butler, with a large body of troops occupied Federal Hill, after which Baltimore was substantially under control of the 1 Some months before his death in 1942 the late Charles McHenry Howard (a grandson of Charles Howard, president of the Board of Police in 1861) placed the papers here printed in the Editor's hands for examination, and offered to write an introduction if the Committee on Publications found them acceptable for the Magazine. Owing to the extraordinary events related and the revelation of an episode unknown in Baltimore history, Mr. Howard's proposal was promptly accepted. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals

To: Principal Staff Committee Members and Representatives of Chesapeake Bay “Headwater” States From: W. Tayloe Murphy, Jr., Chair Chesapeake Bay Program Principals’ Staff Committee Subject: Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals For the past twenty years, the Chesapeake Bay partners have been committed to achieving and maintaining water quality conditions necessary to support living resources throughout the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. In the past month, Chesapeake Bay Program partners (Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Chesapeake Bay Commission) have expanded our efforts by working with the headwater states of Delaware, West Virginia and New York to adopt new cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment. Using the best scientific information available, Bay Program partners have agreed to allocations that are intended to meet the needs of the plants and animals that call the Chesapeake home. The allocations will serve as a basis for each state’s tributary strategies that, when completed by April 2004, will describe local implementation actions necessary to meet the Chesapeake 2000 nutrient and sediment loading goals by 2010. This memorandum summarizes the important, comprehensive agreements made by Bay watershed partners with regard to cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediments, as well as new baywide and local SAV restoration goals. Nutrient Allocations Excessive nutrients in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries promote undesirable algal growth, and thereby, prohibit light from reaching underwater bay grasses (submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV) and depress the dissolved oxygen levels of the deeper waters of the Bay. -

War of 1812 Travel Map & Guide

S u sq u eh a n n a 1 Westminster R 40 r e iv v e i r 272 R 15 anal & Delaware C 70 ke Chesapea cy a Northeast River c o Elk River n 140 Havre de Chesapeake o 97 Grace City 49 M 26 40 Susquehanna 213 32 Flats 301 13 795 95 1 r e Liberty Reservoir v i R Frederick h 26 s 9 u B 695 Elk River G 70 u 340 n Sa p ssaf 695 rass 83 o Riv w er r e d 40 e v i r R R Baltimore i 13 95 v e r y M c i 213 a dd c le o B R n 70 ac iv o k e R r M 270 iv e 301 r P o to m ac 15 ster Che River 95 P 32 a R t i v a 9 e r p Chestertown 695 s 13 co R 20 1 i 213 300 1 ve r 100 97 Rock Hall 8 Leesburg 97 177 213 Dover 2 301 r ive r R e 32 iv M R 7 a r k got n hy te Ri s a v t 95 er e 295 h r p 189 S e o e C v 313 h ve i r C n R R e iv o er h 13 ka 267 495 uc 113 T Whitehall Bay Bay Bridge 50 495 Greensboro 193 495 Queen Milford Anne 7 14 50 Selby 404 Harrington Bay 1 14 Denton 66 4 113 y P 258 a a B t u rn 404 x te 66 Washington D.C. -

Maryland's Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory

Maryland’s Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory by Ralph E. Eshelman and Carl W. Scheffel, Jr. “So long as the tides shall ebb and flow in Choptank River.” From Philemon Downes will, Hillsboro, circa 1796 U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle 7.5 Minute Topographic maps covering the Lower Choptank River (below Caroline County) include: Cambridge (1988), Church Creek (1982), East New Market (1988), Oxford (1988), Preston (1988), Sharp Island (1974R), Tilghman (1988), and Trappe (1988). Introduction The Choptank River is Maryland’s longest river of the Eastern Shore. The Choptank River was ranked as one of four Category One rivers (rivers and related corridors which possess a composite resource value with greater than State signific ance) by the Maryland Rivers Study Wild and Scenic Rivers Program in 1985. It has been stated that “no river in the Chesapeake region has done more to shape the character and society of the Eastern Shore than the Choptank.” It has been called “the noblest watercourse on the Eastern Shore.” Name origin: “Chaptanck” is probably a composition of Algonquian words meaning “it flows back strongly,” referring to the river’s tidal changes1 Geological Change and Flooded Valleys The Choptank River is the largest tributary of the Chesapeake Bay on the eastern shore and is therefore part of the largest estuary in North America. This Bay and all its tributaries were once non-tidal fresh water rivers and streams during the last ice age (15,000 years ago) when sea level was over 300 feet below present. As climate warmed and glaciers melted northward sea level rose, and the Choptank valley and Susquehanna valley became flooded. -

Manokin River Watershed Characterization

Manokin River Watershed Characterization May 2001 In support of Somerset County’s Watershed Restoration Action Strategy for the Manokin River Watershed Product of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources In partnership with Somerset County Parris N. Glendening, Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Lt. Governor Sarah J. Taylor-Rogers, Secretary Stanley K. Arthur, Deputy Secretary David Burke, Director, Chesapeake and Coastal Watershed Service (CCWS) Maryland Department of Natural Resources Tawes State Office Building 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Telephone for CCWS 410-260-8739 Call toll free: 1-877-620-8DNR TTY for the Deaf: 1-410-974-3683 www.dnr.state.md.us The Mission of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources To inspire people to enjoy and live in harmony with their environment, and to protect what makes Maryland unique – our treasured Chesapeake Bay, our diverse landscapes, and our living and natural resources. The facilities and services of the Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, age, national origin, physical or mental disability. Important Contributors to the Manokin River Watershed Characterization Robin Bunting Somerset County Director of Recreation and Parks Max Chambers Flomax Marine Nursery Larry Fykes, Manager, Somerset Soil Conservation District Roman Jesien University of Maryland Eastern Shore Joan Kean Dept. of Technical and Community Services Tom Lawton Dept. of Technical and Community Services Somerset County Alphabetical Order Earl -

Defining the Nanticoke Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail: Nanticoke River Watershed December 2013 Kristin M. Sullivan, M.A.A. - Co-Principal Investigator Erve Chambers, Ph.D. - Principal Investigator Ennis Barbery, M.A.A. - Research Assistant Prepared under cooperative agreement with The University of Maryland College Park, MD and The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, MD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Nanticoke River watershed indigenous cultural landscape study area is home to well over 100 sites, landscapes, and waterways meaningful to the history and present-day lives of the Nanticoke people. This report provides background and evidence for the inclusion of many of these locations within a high-probability indigenous cultural landscape boundary—a focus area provided to the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Advisory Council for the purposes of future conservation and interpretation as an indigenous cultural landscape, and to satisfy the Identification and Mapping portion of the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Cooperative Agreement between the National Park Service and the University of Maryland, College Park. Herein we define indigenous cultural landscapes as areas that reflect “the contexts of the American Indian peoples in the Nanticoke River area and their interaction with the landscape.” The identification of indigenous cultural landscapes “ includes both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife therein associated with historic lifestyle and settlement patterns and exhibiting the cultural or esthetic values of American Indian peoples,” which fall under the purview of the National Park Service and its partner organizations for the purposes of conservation and development of recreation and interpretation (National Park Service 2010:4.22).