MARK-RECAPTURE ASSESSMENT of the RECREATIONAL BLUE CRAB (Callinectes Sapidus) HARVEST in CHESAPEAKE BAY, MARYLAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Maryland's Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory

Maryland’s Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory by Ralph E. Eshelman and Carl W. Scheffel, Jr. “So long as the tides shall ebb and flow in Choptank River.” From Philemon Downes will, Hillsboro, circa 1796 U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle 7.5 Minute Topographic maps covering the Lower Choptank River (below Caroline County) include: Cambridge (1988), Church Creek (1982), East New Market (1988), Oxford (1988), Preston (1988), Sharp Island (1974R), Tilghman (1988), and Trappe (1988). Introduction The Choptank River is Maryland’s longest river of the Eastern Shore. The Choptank River was ranked as one of four Category One rivers (rivers and related corridors which possess a composite resource value with greater than State signific ance) by the Maryland Rivers Study Wild and Scenic Rivers Program in 1985. It has been stated that “no river in the Chesapeake region has done more to shape the character and society of the Eastern Shore than the Choptank.” It has been called “the noblest watercourse on the Eastern Shore.” Name origin: “Chaptanck” is probably a composition of Algonquian words meaning “it flows back strongly,” referring to the river’s tidal changes1 Geological Change and Flooded Valleys The Choptank River is the largest tributary of the Chesapeake Bay on the eastern shore and is therefore part of the largest estuary in North America. This Bay and all its tributaries were once non-tidal fresh water rivers and streams during the last ice age (15,000 years ago) when sea level was over 300 feet below present. As climate warmed and glaciers melted northward sea level rose, and the Choptank valley and Susquehanna valley became flooded. -

Description of the Choptane Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE CHOPTANE QUADRANGLE. By Benjamin Leroy Miller. INTRODUCTION. ment of water power, are located such important towns and dip. The oldest strata dip 50 to 60 feet to the mile in some cities as Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, Wash places, but the succeeding beds are progressively less steeply LOCATION AND AREA. ington, Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, Raleigh, Cam- inclined and in the youngest deposits a dip of more than a few The Choptank quadrangle lies between parallels 38° 30' and den, Columbia, Augusta, Macon, and Columbus. A line drawn feet to the mile is uncommon. 39° north latitude and meridians 76° and 76° 30' west through these places would approximately separate the Coastal longitude. It includes one-fourth of a square degree of the Plain from the Piedmont Plateau. TOPOGRAPHY. earth's surface and contains 931.51 square miles. From north The Coastal Plain is divided by the present shore line into RELIEF. to south it measures 34.5 miles and from east to west its mean two parts a submerged portion, known as the continental INTRODUCTION. width is 27 miles, as it is 27.1 miles wide along the southern shelf or continental platform, and a,n emerged portion, com and 26.9 miles along the northern border. monly called the Coastal Plain. In some places the line sepa The altitude of the land in the Choptank quadrangle ranges rating the two parts is marked by a sea cliff of moderate from sea level to 120 feet above. The highest point lies about 77 height, but commonly they grade into each other with scarcely 2 miles south of Annapolis on the western margin of the quad perceptible change and the only mark of separation is the shore rangle. -

Distribution and Abundance of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in the Chesapeake Bay: a Scientific Summary

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-1-1982 Distribution and Abundance of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in the Chesapeake Bay: A Scientific Summary Robert J. Orth Virginia Institute of Marine Science Kenneth A. Moore Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Orth, R. J., & Moore, K. A. (1982) Distribution and Abundance of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in the Chesapeake Bay: A Scientific Summary. Special Reports in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering (SRAMSOE) No. 259. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V58454 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE OF SUBMERGED AQUATIC VEGETATION IN THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: A SCIENTIFIC SUMMARY by Robert J. Orth and Kenneth A. Moore Virginia Institute of Marine Science of the College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 Special Report No. 259 in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE OF SUBMERGED AQUATIC VEGETATION IN THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: A SCIENTIFIC SUMMARY by Robert J. Orth and Kenneth A. Moore Virginia Institute of Marine Science of the College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 Special Report No. 259 in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering CONTENTS List of Figures •• . iii List of Tables. iv 1. Introduction. 1 2. Methods. 4 3. Present Distribution •• 5 4. -

Maryland's Vision for Oysters

Maryland’s Vision for Oysters Establish an expanding and sustainable population of native oysters in significant portions of Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Establish a private aquaculture industry that emerges as a major economic contributor to the State of Maryland while maintaining a more targeted and scientifically managed wild oyster fishery. Photo © Michael Eversmeier Status of Oyster Population and Industry The average number of reported oyster harvesters between 2002 and 2006 was 529. This is a significant decrease from the more than 2,000 harvesters that the oyster fishery supported prior to the disease epizootics of the mid-1980s. Oysters harvested from Chesapeake Bay decreased from over 2 million bushels/year in the 1980’s to just over 100 thousand bushels in 2008-2009. Overall adult abundance in 2008-2009 was approximately 3.5 billion oysters, 1% of the historic population. MARYLAND’S 10-POINT OYSTER RESTORATION PLAN 1. Focus on targeted restoration strategies to achieve ecological and economic goals 2. Expand the sanctuary program 3. Support a more focused and scientifically managed wild oyster fishery 4. Shift commercial production to aquaculture 5. Rehabilitate oyster bar habitat 6. Manage against oyster disease 7. Increase hatchery production 8. Enhance law enforcement 9. Increase citizen involvement 10. Integrate inmate labor Maryland’s Proposed Oyster Sanctuary Network Proposed sanctuary areas include the Magothy River, the area between the mouths of the Patapsco and Back Rivers bounded by the main channel, Upper St. Mary’s River, Point Lookout, Little Choptank River, Upper Patuxent River, mainstem portion and lower tributaries of Choptank River, and area between the main channel and shore from Hooper Strait to Smith Island. -

STATE of MARYLAND BOARD of NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of GEOLOGY, MINES and WATER RESOURCES Joseph T

STATE OF MARYLAND BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., Director BULLETIN 6 SHORE EROSION IN TIDEWATER MARYLAND CaliforniaState Division of Mines RECEIVED JAN 2 41950 library San Francisco, California BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 1949 Composed and Printed at Waverly Press, Inc. Baltimore, Md., U.S.A. COMMISSION ON GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Arthue B. Stewart, Chairman Baltimore Holmes D. Baker Frederick Harry R. Hall Hyattsville Joseph C. Lore, Jr Solomons Island Mervin A. Pentz Denton CONTENTS The Shore Erosion Problem. By Joseph T. Singewald, Jr 1 The Maryland Situation 1 Federal Legislation 2 Policy in Other Slates 2 Uniqueness of the Maryland Problem 3 Shore Erosion Damage in Maryland 4 Methods of Shore Front Protection 4 Examples of Shore Erosion Problems 6 Miami Beach 6 New Bay Shore Park 8 Mountain Point, Gibson Island 10 Tall Timbers, Potomac River 12 Tydings on the Bay and Log Inn, Anne Arundel County 14 Sandy Point State Park 15 What Should be done about Shore Erosion 16 The Shore Erosion Measurements. By Turhit H. Slaughter 19 Definition of Terms 19 Anne Arundel County 21 Baltimore County 28 Calvert County 31 Caroline County 35 Cecil County 37 Charles County 40 Dorchester County. 45 Harford County 54 Kent County 61 Prince Georges County 66 Queen Annes County 69 St. Marys County 75 Somerset County 84 Talbot County 91 Wicomico County 107 Worcester County 109 Summary of Shore Erosion in Tidewater Maryland 115 Navigation Restoration Expenditures. By Turbit If. Slaughter 119 References 121 Description of Plates 29 to 35 123 LIST OF TABLES 1. -

Bay Grasses Backgrounder

Bay Grasses Backgrounder - Page 1 of 5 Upper Bay Zone In the Upper Bay Zone (21 segments extending south from the Susquehanna River to the Bay Bridge), underwater bay grasses increased 21 percent from 18,922 acres in 2007 to 22,954 acres in 2008. Ten of the 21 segments increased by at least 20 percent and by at least 12 acres from 2007 totals: 21%, Northern Chesapeake Bay Segment: 1,833 acres (2007) vs. 1,008 acres (2008) 21%, Northern Chesapeake Bay Segment 2: 11,725 acres (2007) vs. 14,194 acres (2008) 59%, Northeast River: 116 acres (2007) vs. 183 acres (2008) 70%, Upper Chesapeake Bay: 373 acres (2007) vs. 633 acres (2008) 50%, Sassafras River Segment: 1,368 acres (2007) vs. 551 acres (2008) 1204%, Sassafras River Segment 2: 5 acres (2007) vs. 52 acres (2008) 40%, Gunpowder River Segment 1: 558 acres (2007) vs. 783 acres (2008) 50%, Middle River: 551 acres (2007) vs. 828 acres (2008) 53%, Upper Central Chesapeake Bay: 124 acres (2007) vs. 188 acres (2008) 23%, Lower Chester River: 67 acres (2007) vs. 84 acres (2008) None of the 21 segments decreased by at least 20 percent and by at least 12 acres from 2007 totals. Two of the 21 segments remained unvegetated in 2008. Acres of SAV & Goal Attained Upper Chesapeake Bay Region Segment 2007 2008 Restoration Goal 2008 % of goal Northern Chesapeake Bay Segment 1 834 1007 754 134 Northern Chesapeake Bay Segment 2 11726 14194 12149 117 Northern Chesapeake Bay Total 12560 15202 12903 118 Northeast River 115 183 89 205 Elk River Segment 1 1590 1907 1844 103 Elk River Segment 2 391 440 190 232 -

2018 Maryland Oyster Restoration Update

2018 Maryland Oyster Restoration Update Progress in the Choptank Complex (Harris Creek, Little Choptank River, and Tred Avon River Oyster Sanctuaries) June 2019 The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, which guides the work of the Chesapeake Bay Program, commits state and federal partners to “restore native oyster habitat and populations in 10 Bay tributaries Harris Creek by 2025, and ensure their protection.” This reinforces the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Oyster Restoration Master Plan and Maryland’s Oyster Restoration and Tred Avon Aquaculture Development Plan. To achieve this outcome, the U.S. Army Corps of Little Engineers’ Baltimore District (USACE), the National Choptank Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the St. Mary’s Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Manokin and the Oyster Recovery Partnership (ORP) formed the Maryland Oyster Restoration Interagency Work- group (hereafter, Workgroup) under the auspices of the Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team (GIT) of the Chesapeake Bay Program. The Workgroup, with guidance from consulting sci- entists and the public, coordinates large-scale oyster restoration in selected Maryland tributaries. To date, the Workgroup has developed “oyster restoration tributary plans” that describe how three Maryland Se l ected for l arge-scale oyster tributaries will be restored and monitored, consistent restoration with standards described in the Chesapeake Bay Oys- Recommendedfor large-scale 1 ter Metrics report . oyster restoration This update describes progress on implementing oyster restoration tributary plans for Harris Creek2, the Little Choptank River3, and the Tred Avon River4. The Upper St. Mary’s River was selected by the Sustainable Fisheries GIT in December 2018; the Manokin River was recommended by DNR as the fifth Maryland tributary in September 2018. -

Spatial Variation in Fishery Exploitation of Mature Female Blue Crabs (C

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2018 Spatial variation in fishery exploitation of mature female blue crabs (C. sapidus) in Chesapeake Bay Corey Travis Corrick University of North Florida Suggested Citation Corrick, Corey Travis, "Spatial variation in fishery exploitation of mature female blue crabs (C. sapidus) in Chesapeake Bay" (2018). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 798. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/798 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2018 All Rights Reserved Spatial variation in fishery exploitation of mature female blue crabs (C. sapidus) in Chesapeake Bay by Corey Travis Corrick A thesis submitted to the Department of Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Biology UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES April, 2018 Unpublished work © Corey Travis Corrick This Thesis titled “Spatial variation in fishery exploitation of mature female blue crabs (C. sapidus) in Chesapeake Bay” is approved: By the thesis committee: Date _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Eric G. Johnson Committee Chair _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Matthew B. Ogburn Committee Member _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Kelly Smith Committee Member Accepted for the Department of Biology: _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Cliff Ross Chair, Department of Biology Accepted for the College of Arts and Sciences: _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. George Rainbolt Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Accepted for the University: _________________________________________________ __________________ Dr. -

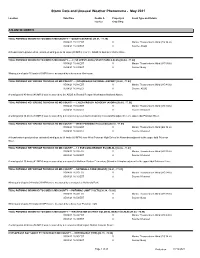

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - May 2021

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - May 2021 Location Date/Time Deaths & Property & Event Type and Details Injuries Crop Dmg ATLANTIC NORTH TIDAL POTOMAC INDIAN HD TO COBB IS MD COUNTY --- QUANTICO (KNYG) [38.51, -77.30] 05/04/21 15:32 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/04/21 15:32 EST 0 Source: ASOS A thunderstorm produced an estimated wind gust to 34 knots (39 MPH) near the ASOS at Quantico Marine Base. TIDAL POTOMAC INDIAN HD TO COBB IS MD COUNTY --- 2.7 SE LEESYLVANIA STATE PARK (LSLVN) [38.64, -77.22] 05/04/21 15:48 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 36 kt) 05/04/21 16:03 EST 0 Source: Buoy Wind gusts of up to 36 knots (41 MPH) were measured by a buoy near Occoquan. TIDAL POTOMAC KEY BRIDGE TO INDIAN HD MD COUNTY --- (DCA)REAGAN NATIONAL AIRPORT [38.86, -77.03] 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 40 kt) 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Source: ASOS A wind gust of 40 knots (46 MPH) was measured by the ASOS at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. TIDAL POTOMAC KEY BRIDGE TO INDIAN HD MD COUNTY --- LYLES-CROUCH ACADEMY (AXDRA) [38.80, -77.05] 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 34 kt) 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A wind gust of 34 knots (39 MPH) was measured by a mesonet at Lyles-Crouch Academy in Alexandria adjacent to the upper tidal Potomac River. TIDAL POTOMAC KEY BRIDGE TO INDIAN HD MD COUNTY --- WEST POTOMAC HS (ALEXD) [38.78, -77.07] 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/04/21 16:04 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A thunderstorm produced an estimated wind gust to 34 knots (39 MPH) near West Potomac High School in Alexandria adjacent to the upper tidal Potomac River. -

THE SEVERN RIVER ASSOCIATION BOX 146 • ANNAPOLIS, MD 21404 • Severnriver.Org • 443-569-3556 Voicemail

THE SEVERN RIVER ASSOCIATION BOX 146 • ANNAPOLIS, MD 21404 • severnriver.org • 443-569-3556 voicemail (Emails @severnriver.org) September 6, 2016 Officers: President Lynne D. Rockenbauch 410-987-6042 Contact: Lynne D. Rockenbauch , President, 410-987-6042, [email protected] president@ Vice President Tom Guay, Communications Director, 443-716-6776, [email protected] Rusty Gowland 410-530-9087 Treasurer Oysters – What We’re Doing To Restore Them Lee Meadows 410.849.3466 Recording Secretary Bob vom Saal With all the ups and downs oysters face – from dead zones, sediment and nutrient 410-987-4476 pollution, diseases and over harvesting – what type of future is in store for the oyster in Communications Director Tom Guay the Chesapeake Bay? 443-716-6776 [email protected] Join us Tuesday evening, September 20, to hear about oysters and their future in Member Communities: Admiral Heights Improvement Assn Maryland waters at the Severn River Association’s (SRA) next Educational Series Amberley Community Association Anchorage Swim Club Annapolis Conservancy Board meeting at Union Jack’s Pub in Parole. Annapolis Neck Penninsula Fed. Annapolis Roads Property OwnrAssn Arden Civic Association Our guest speaker will be Stephanie Westby, who serves as the National Oceanographic Arnold Preservation Council Bay Ridge Civic Association and Aeronautics Administration’s (NOAA) coordinator for oyster restoration in the Bay Ridge Trust Inc Bayberry Hill Property Ownrs Assn Belleview Estates Community Assn Chesapeake. Belvoir Farms Homeowners Assn Bembe Beach Association Ben Oaks Civic Association Most of NOAA's recent oyster restoration work in Maryland Bluff Point Community Association Bretton Woods Home Owners Assn Brown’s Pond Improvement Assn has focused on the Eastern Shore. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1937, Volume 32, Issue No. 1

MSA SC 5&81 -1 - U5 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDEK THE AUTHORITY OP THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXXII BALTIMORE 1937 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXII. PAGE JOHN W. M. LEE, 1848-1896. By Ruth Lee Briscoe, 1 LETTEES OF JAMES RUMSET. Edited iy James A. Padgett, Ph.D., 10, 136, 271 A NEW MAP OP THE PEOVIKCB OF MARYLAND IN NORTH AMERICA. By J. Louis Kuethe, 28 BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1633. Contributed by Louis Dow Scisco, 30 LETTERS OF CHARLES CARROLL, BARRISTER. Continued from Vol. XXXI, 4, 35, 174, 348 NOTES, QUERIES, REVIEWS, .... 47, 192, 291, 292, 376, 385 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 53, 190, 381 LIST OP MEMBERS, 73 POE'S LITERARY BALTIMORE. By John C. French, 101 SOME RECENTLY-FOUND POEMS ON THE CALVERTS. By Walter B. Norris, 112 GOVERNOR HORATIO SHABPB AND HIS MARYLAND GOVERNMENT. By Paul H. Giddens, 156 A LOST COPY-BOOK OP CHARLES CARROLL OF CARROLLTON. By J. G. D. Paul, 193 AN UNPUBLISHED LETTER. By Roger B. Taney, 225 HISTORIC FORT WASHINGTON. By Amy Cheney Clinton, .... 228 THE PAPERS OP THE MARYLAND STATE COLONIZATION SOCIETY. By William D. Eoyt, Jr., 247 * " PATOWMECK ABOVE YE INHABITANTS." By William B. Marye, . 293 JOHN NELSON MCJILTON. By W. Bird Terwilliger, 301 THE SIZES OF PLANTATIONS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MARYLAND. By T. J. Wyckoff, 331 INCIDENTS OP THE WAR OP 1812 . From the " Baltimore Patriot," . 340 THE SOCIETY OP THE CINCINNATI, 369 THE ROCKHOLDS OP EARLY MARYLAND. By Nannie Ball Nimmo, . 371 'BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1684. By Louis Dow Scisco 286 ARCHIVES OF M^HYLA^ISro Edited by J.