Great Linford Manor P Ark Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Linford M1

Conservation and Archaeology Conservation Area Review Programme Great Linford Conservation Area Review Consultation Draft The Manor House, Great Linford www.milton-keynes.gov.uk/planning-and-building/conservation-and-archaeology This document is to be read in conjunction with the General Information Document available on line Conservation Area Review Programme - Great Linford Conservation Area Review - Consultation Draft Conservation Area Review Programme - Great Linford Conservation Area Review - Consultation Draft Historical Background Since the 1970’s there have been further significant changes relating to new town developments in the Archaeological investigation suggests that there has form of a series of individual housing developments of been a settlement in the area of the church since late varying quality that have infilled open land around the Saxon times. The early settlement lay on a lost section newly built St Leger Drive to the west and Marsh Road of the existing High Street which seems to have to the east. The effect has been to conceal most of the extended down the hill, to where the Manor Ponds former village within the newer developments so that now are, before turning westwards to the church and it has to be sought out rather than arrived at just by then northwards in the direction of the river Great Ouse following a principal route through the grid square. where it would once have met with the east-west aligned road connecting Wolverton, Stony Stratford and Newport Pagnell1. The church and some houses stood on higher ground above the river but, perhaps in response to the marshy nature of the lower ground, the road was diverted eastward from where the Nag’s Head now stands, along the brow of the hill, before heading north once more, leaving the church and early settlement isolated. -

Milton Keynes Council Event/Activity Summary Report 05/03/2018 Number of Records: 33

Milton Keynes Council Event/Activity Summary Report 05/03/2018 Number of records: 33 Event Ref, Type Name Dates Organisation (EMK1293) Hyde Solar Farm, Olney - Watching Brief 03/01/2017 - 27/01/2017, occasionally Cotswold Archaeology Event - Survey An archaeological watching brief was undertaken by Cotswold Archaeology during groundworks associated with construction of a solar farm; to include the installation of solar panels, underground cabling, inverter/transformer stations, DNO, client substation, spare parts container, landscaping and other associated works at Hyde Farm, Olney, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire. No features or deposits of archaeological significance were observed during groundworks, and no artefactual material pre-dating the modern period was recovered. (EMK1294) Land at Walkers Bridge, Olney - Watching Brief 01/02/2017 Archaeological Solutions Ltd / Hertfordshire Archaeological Trust Event - Intervention Monitoring of the excavations for the footings of the new agricultural building in the northeastern corner of Walkers Bridge Field revealed a Roman ditch (F1009), orientated northwest/southeast and a Roman pit (F1004). The latter cut undated Pit F1007. The fill (L1008) of Pit F1007 consisted of a compact pale grey, with red, orange and yellow mottling, crushed limestone. This suggests the possibility that the feature may have been a footing or pad for a large post. Pit F1004 may represent the deliberate removal of the post. (EMK1295) Outbuilding, New Inn, Bradwell Road, New 31/01/2017 Bancroft Heritage Services Bradwell -

Updated Electorate Proforma 11Oct2012

Electoral data 2012 2018 Using this sheet: Number of councillors: 51 51 Fill in the cells for each polling district. Please make sure that the names of each parish, parish ward and unitary ward are Overall electorate: 178,504 190,468 correct and consistant. Check your data in the cells to the right. Average electorate per cllr: 3,500 3,735 Polling Electorate Electorate Number of Electorate Variance Electorate Description of area Parish Parish ward Unitary ward Name of unitary ward Variance 2018 district 2012 2018 cllrs per ward 2012 2012 2018 Bletchley & Fenny 3 10,385 -1% 11,373 2% Stratford Bradwell 3 9,048 -14% 8,658 -23% Campbell Park 3 10,658 2% 10,865 -3% Danesborough 1 3,684 5% 4,581 23% Denbigh 2 5,953 -15% 5,768 -23% Eaton Manor 2 5,976 -15% 6,661 -11% AA Church Green West Bletchley Church Green Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1872 2,032 Emerson Valley 3 12,269 17% 14,527 30% AB Denbigh Saints West Bletchley Saints Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1292 1,297 Furzton 2 6,511 -7% 6,378 -15% AC Denbigh Poets West Bletchley Poets Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1334 1,338 Hanslope Park 1 4,139 18% 4,992 34% AD Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 2361 2,367 Linford North 2 6,700 -4% 6,371 -15% AE Simpson Simpson & Ashland Simpson Village Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 495 497 Linford South 2 7,067 1% 7,635 2% AF Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1747 2,181 Loughton Park 3 12,577 20% 14,136 26% AG Granby Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Granby Bletchley -

Great Linford Manor Park Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire

Great Linford Manor Park Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire Archaeological Watching Brief for The Parks Trust CA Project: 660924 Site Code: GLM17 CA Report: 17554 HER Ref: EMK1317 October 2017 Great Linford Manor Park Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire Archaeological Watching Brief CA Project: 660924 Site Code: GLM17 HER Ref: EMK1317 CA Report: 17554 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 6/9/17 SB and AKM JN Draft Internal review B 10/10/17 AKM PB Draft Internal review MLC This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Great Linford Manor Park, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire: Archaeological Watching Brief CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 4 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 5 4. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 6 5. RESULTS (FIG. -

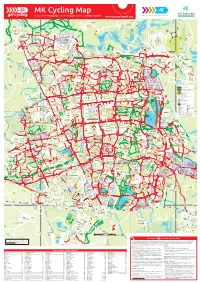

MK Cycling Map a Map of the Redways and Other Cycle Routes in Milton Keynes

MK Cycling Map A map of the Redways and other cycle routes in Milton Keynes www.getcyclingmk.org Stony Stratford A B C Little D Riv E Linford er Great O Nature Haversham Dovecote use Reserve Ouse Valley Park Spinney Qu e W en The H Grand Union Canal a A5 Serpentine te i E r g le L h a se Haversham a n u S Riv t O ne o er Grea Village School t r r e S e tr Burnt t e et Covert Sherington Little M Russell Linford 1 Stony Stratford Street Ouse Valley Park Park L Library i School St Mary and St Giles t t Lakelane l Ousebank C of E Junior School Co e lt L Spinney WOLVERTON s H i ol n m f MILL Road o Old W r Wolverton Ro olv Manor d ad Strat Tr ert ford Road on L ad i R Farm a Lathbury o n oad n R Slated Row i e n t t y Ouse Valley Park to STONY e School g R n e i o r r t Stantonbury STRATFORD a OLD WOLVERTON Haversham e L d h o S Lake y S n r Lake a d o W o n WOLVERTON MILL W d n Portfields e Lathbury a s e lea EAST W s R S s o E Primary School t House s tr R oa at e b C n fo r o hi u e r u ch n e d c rd ele o d The R r O rt u o y swo y H e Q ad n r y il t Radcliffe t l lv R h 1 a i n Lan 1 e v e e Ca School Wolverton A r er P r G Gr v L e eat e v Wyvern Ou a i n R M se Bury Field l A u k il d School l L e e i H din i l y gt a t s f le on A t al WOLVERTON MILL l o n e e G ve C Wolverton L r h G u a L a d venu Queen Eleanor rc i A SOUTH r h Library n n S C Primary School e A tr R Blackhorse fo e H1 at M y ee d - le t iv n r a y sb e Stanton REDHOUSE d o a u r Bradwell o Lake g d R r V6 G i a L ew y The r n Newport n n o g o e Low Park PARK a -

Ounded Orners 0˚

X5 to Oxford X6 to Northampton 33 33A to Northampton via Hanslope Stony 6 Haversham Stratford X60 to Aylesbury Stratford Road 33 Wolverton Rd 33A 1 2 14 Poets 301 18 Estate Wolverton 7 23 Redhouse New 6 Church St Oakridge Park 14 Bradwell Newport Park Newport Wolverton 21 to Olney & Lavendon London Greenleys Road 23 21 Pagnell Road 23 5 1 21 24 25 Market Hill 23 Windsor 33 24 24 Street 25 301 Fullers 6 33A Blue 7 23 Great Marsh 1 25 18 2 C10 North Slade 14 Bridge 33 33A 7 Linford Drive 2 6 1 Green Crawley Stacey Bradville Stantonbury Park C10 C10 to Bedford via Craneld 5 Giard Blakelands Tickford End Kiln Bushes Bancroft 1 1 2 301 Hodge 33 Park Fairelds Farm Lea 6 33A 23 25 24 24 2 25 X5 5 C10 X6 7 21 Two Mile 33 33A 6 Linford Wood X5 to Cambridge via Bedford X60 18 Tongwell Ash 14 Pennyland Bolbeck 24 301 301 301 Bradwell Heelands 23 Neath Hill 24 1 Park C10 25 X5 Great 25 Whitehouse Holm Bradwell Conniburrow Downs 2 28 18 Barn Downhead Willen 301 Common 28 Loughton Park 1 Lovat 28 Lodge 2 7 Fields C10 24 21 300 300 25 2 2 Crownhill X5 Moulsoe 7 Central X5 X5 C1 C11 to Bedford via Craneld Grange Loughton Campbell C1 C11 Farm 28 Milton Rounded Campbell Park Fox Milne Shenley 24 24 25 Keynes Park 8 MK Coachway Route Frequency Corners Church End 25 Park and Ride Number Route every 28 7 Loughton Shenley 8 28 28 8 Middleton 1 Newton Leys - Bletchley - Central Milton Keynes - Newport Pagnell 30 mins Wood 50 5 Woolstone 24 1 150 6 28 4 Broughton Grange Farm - CMK - Willen - Redhouse Park - Newport Pagnell 20 mins 8 Knowlhill 8 25 2 Oldbrook -

Late Medieval Buckinghamshire

SOLENT THAMES HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT MEDIEVAL BUCKINGHAMSHIRE (AD 1066 - 1540) Kim Taylor-Moore with contributions by Chris Dyer July 2007 1. Inheritance Domesday Book shows that by 1086 the social and economic frameworks that underlay much of medieval England were already largely in place. The great Anglo Saxon estates had fragmented into the more compact units of the manorial system and smaller parishes had probably formed out of the large parochia of the minster churches. The Norman Conquest had resulted in the almost complete replacement of the Anglo Saxon aristocracy with one of Norman origin but the social structure remained that of an aristocratic elite supported by the labours of the peasantry. Open-field farming, and probably the nucleated villages usually associated with it, had become the norm over large parts of the country, including much of the northern part of Buckinghamshire, the most heavily populated part of the county. The Chilterns and the south of the county remained for the most part areas of dispersed settlement. The county of Buckinghamshire seems to have been an entirely artificial creation with its borders reflecting no known earlier tribal or political boundaries. It had come into existence by the beginning of the eleventh century when it was defined as the area providing support to the burh at Buckingham, one of a chain of such burhs built to defend Wessex from Viking attack (Blair 1994, 102-5). Buckingham lay in the far north of the newly created county and the disadvantages associated with this position quickly became apparent as its strategic importance declined. -

Details of Decisions Made on Planning Applications Week Beginning 31/05/2010

Details of decisions made on planning applications week beginning 31/05/2010 10/00821/FUL Type: No Decision Erection of single storey rear extension Made (Retrospective) Bletchley & Fenny Team: South At: 86 Water Eaton Road Bletchley Milton Stratford Town Keynes MK2 3AN Council Decision date: 01/06/2010 For: Mrs Marge Green Decision: Invalid Application Returned ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10/00204/FUL Type: Delegated Erection of 2 one bedroomed flats with new Decision vehicular access Campbell Park Team: No Code [] At: 15 Trueman Place Oldbrook Milton Parish Council Keynes MK6 2HE Decision date: 01/06/2010 For: Mr Glenn Armstrong Decision: Application Refused ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10/00638/FUL Type: Delegated Erection of summerhouse and store to replace Decision existing gazebo Castlethorpe Team: North At: Castlethorpe Lodge Hanslope Road Parish Council Castlethorpe Milton Keynes MK19 7HD Decision date: 02/06/2010 For: Mrs Joan Harrison Decision: Application Permitted ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10/00352/FUL Type: Delegated Construction of detached two storey dwelling Decision with integral garage, and relocation of vehicular access Emberton Parish Team: North At: 18 Olney Road Emberton Olney MK46 Council 5BX Decision date: 02/06/2010 For: Mr Lawrence Welch Decision: -

Houses and Apartments That Are Different Introduction

MILTON MEADOW Houses and apartments that are different Introduction With Milton Keynes on your doorstep you have access Welcome to Milton Meadow to all the retail and leisure activities that a thriving town has to offer, whilst on a daily basis you are free to enjoy a more relaxed village atmosphere. All of the homes are individually designed by local developer, Paul Newman New Homes and enjoy high ceilings, bespoke kitchens and a high specification. Milton Meadow is a breath of fresh air. A contemporary collection of eighteen 3 and 4 bedroom houses and five 2 bedroom apartments situated in the heart of New Bradwell. These individual, architect-designed homes are built using a high quality, superior brick. Each home is light and airy with large modern windows, 9ft high ceilings on the ground floor and fibre broadband connectivity as standard. All homes enjoy an abundance of living space featuring French doors leading out to the rear garden or balcony. All 4 bedroom homes also benefit from a roof terrace on the second floor to enjoy more outside space. CGI is for illustrative purposes only. 1 Siteplan R Milton Meadow is a contemporary IVER GRE development with two rows of AT OUSE houses and three apartment blocks in a peaceful cul-de-sac location close to local amenities. 21-25 15-20 10-14 9 26 27 8 Key Type Bedrooms Plots 7 28 Cherry House 3 5, 6, 30, 31, 32 29 6 Sycamore House 3 3, 4 5 30 Ash House 4 1, 33 31 Oak House 4 7, 8, 27, 28, 29 4 3 Beech House 4 2, 9, 26, 34 32 Willow Apartments 2 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 34 33 1 2 NEWPORT ROAD 2 Siteplan is for indicative purposes only. -

Milton Keynes Councillors

LIST OF CONSULTEES A copy of the Draft Telecommunications Systems Policy document was forwarded to each of the following: MILTON KEYNES COUNCILLORS Paul Bartlett (Stony Stratford) Jan Lloyd (Eaton Manor) Brian Barton (Bradwell) Nigel Long (Woughton) Kenneth Beeley (Fenny Stratford) Graham Mabbutt (Olney) Robert Benning (Linford North) Douglas McCall (Newport Pagnell Roger Bristow (Furzton) South) Stuart Burke (Emerson Valley) Norman Miles (Wolverton) Stephen Clark (Olney) John Monk (Linford South) Martin Clarke (Bradwell) Brian Morsley (Stantonbury) George Conchie (Loughton Park) Derek Newcombe (Walton Park) Stephen Coventry (Woughton) Ian Nuttall (Walton Park) Paul Day (Wolverton) Michael O’Sullivan (Loughton Park) Reginald Edwards (Eaton Manor) Michael Pendry (Stony Stratford) John Ellis (Ouse Valley) Alan Pugh (Linford North) John Fairweather (Campbell Park) Christopher Pym (Walton Park) Brian Gibbs (Loughton Park) Hilary Saunders (Wolverton) Grant Gillingham (Fenny Stratford) Patricia Seymour (Sherington) Bruce Hardwick (Newport Pagnell Valerie Squires (Whaddon) North) Paul Stanyer (Furzton) William Harnett (Denbigh) Wedgwood Swepston (Emerson Euan Henderson (Newport Pagnell Valley) North) Cec Tallack (Campbell Park) Irene Henderson (Newport Pagnell Bert Tapp (Hanslope Park) South) Christine Tilley (Linford South) David Hopkins (Danesborough) Camilla Turnbull (Whaddon) Janet Irons (Bradwell Abbey) Paul White (Danesborough) Harry Kilkenny (Stantonbury) Isobel Wilson (Campbell Park) Michael Legg (Denbigh) Kevin Wilson (Woughton) David -

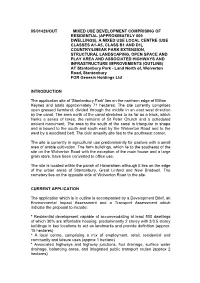

05/01429/Out Mixed Use Development Comprising Of

05/01429/OUT MIXED USE DEVELOPMENT COMPRISING OF RESIDENTIAL (APPROXIMATELY 500 DWELLINGS), A MIXED USE LOCAL CENTRE (USE CLASSES A1-A5, CLASS B1 AND D1), COUNTRY/LINEAR PARK EXTENSION, STRUCTURAL LANDSCAPING, OPEN SPACE AND PLAY AREA AND ASSOCIATED HIGHWAYS AND INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS (OUTLINE) AT Stantonbury Park - Land North of, Wolverton Road, Stantonbury FOR Genesis Holdings Ltd INTRODUCTION The application site of 'Stantonbury Park' lies on the northern edge of Milton Keynes and totals approximately 71 hectares. The site currently comprises open grassed farmland, divided through the middle in an east west direction by the canal. The area north of the canal stretches to as far as a track, which flanks a series of lakes, the remains of St Peter Church and a scheduled ancient monument. The area to the south of the canal is triangular in shape and is bound to the south and south east by the Wolverton Road and to the west by a woodland belt. The civic amenity site lies to the southwest corner. The site is currently in agricultural use predominantly for pasture with a small area of arable cultivation. The farm buildings, which lie to the southeast of the site on the Wolverton Road with the exception of the main house and a large grain store, have been converted to office use. The site is located within the parish of Haversham although it lies on the edge of the urban areas of Stantonbury, Great Linford and New Bradwell. The cemetery lies on the opposite side of Wolverton Road to the site. CURRENT APPLICATION The application which is in outline is accompanied by a Development Brief, an Environmental Impact Assessment and a Transport Assessment which indicate the proposal to include: * Residential development capable of accommodating at least 500 dwellings of which 30% are affordable housing, predominantly 2 storey with 3/3.5 storey buildings in key locations to act as landmarks and provide definition (approx. -

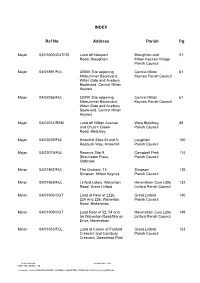

INDEX Ref No Address Parish Pg

INDEX Ref No Address Parish Pg Major 03/01600/OUTEIS Land off Newport Broughton and 21 Road, Broughton Milton Keynes Village Parish Council Major 04/01891/FUL CBXIII Site adjoining Central Milton 61 Midsummer Boulevard, Keynes Parish Council Witan Gate and Avebury Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes Major 04/02056/FUL CBXIII Site adjoining Central Milton 61 Midsummer Boulevard, Keynes Parish Council Witan Gate and Avebury Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes Major 04/02014/REM Land off Wilton Avenue West Bletchley 88 and Church Green Parish Council Road, Bletchley Major 04/02039/FUL Knowlhill Sites M and N, Loughton 100 Roebuck Way, Knowlhill Parish Council Major 04/02075/FUL Reserve Site 9, Campbell Park 114 Shackleton Place, Parish Council Oldbrook Minor 04/01862/FUL The Orchard, 13 Simpson 126 Simpson, Milton Keynes Parish Council Minor 04/01869/FUL Linford Lakes, Wolverton Haversham Cum Little 132 Road, Great Linford Linford Parish Council Minor 04/01903/OUT Land at Rear of 222b, Great Linford 140 224 And 226, Wolverton Parish Council Road, Blakelands Minor 04/01909/OUT Land Rear of 52, 54 and Haversham Cum Little 149 56 Wolverton Road/Manor Linford Parish Council Drive, Haversham Minor 04/01953/FUL Land at Corner of Fairford Great Linford 153 Crescent and Cornbury Parish Council Crescent, Downhead Park DEVELOPMENT 9 FEBRUARY 2005 CONTROL COMMITTEE L:\Committee\2004-05\DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE\9 FEBRUARY 2005\09-02-05_INDEX.doc Minor 04/02002/FUL Linford Lakes, Wolverton Haversham Cum Little 164 Road, Great Linford Linford Parish Council