Nature, Nurture and Chance: the Lives of Frank and Charles Fenner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Record

AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY RECORD I b Number 28 I fi: The Australian Veterinary History Record is published by the Australian Veterinary History Society in the months of March, July and November. Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea, 13 Sunset Avenue, Carnden NSW 2570. Officer bearers of the Society. President: Dr M. Baker Librarian: Dr R. Roe Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea Committee Members: Dr Patricia. McWhirter Dr Paul Canfield Dr Trevor Faragher Dr John Fisher AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY RECORD JuIy 2000 Number 28 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING - Melbourne - 2003 The next meeting of the Society will be held in Melbourne in 2001 as part of the AVA Conference with Dr Trevor Faragher as the Local Organism. This is the first caIl for papers md those interested should contact Trevor (28 Parlington Street, Canterbury Vic 3 126, phone (03) 9882 64 12, E-mail [email protected]. ANNUAL MEETING - Sydney 2000 The Annual Meeting of the Australian Veterinaq History Society for 2000 was held at the Veterinary School, University of Sydney on Saturday 6 May. There was a presentation of four papers on veterinary history during the afternoon. These were followed by the Annual General Meeting details of which are given below. In the evening a very pleasant dher was held in the Vice Chancellor's dining room. MINUTES OF THE 9TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY SOCIETY: SYDNEY MAY 6 2000 at 5:00 pm PRESENT Bob Taylor; Len Hart; PauI Canfield; Rhonda Canfield; John Fisher; John Bolt; Mary Holt; Keith Baker; Rosalyn Baker; Peter Mylrea; Margaret Mylrea; Doug Johns; Chris Bunn;; John Holder APOLOGES Dick Roe; Bill Pryor; Max Barry; Keith Hughes; Harry Bruhl; Geoff Kenny; Bruce Eastick; Owen Johnston; Kevin Haughey; Bill Gee; Chas SIoan PREVIOUS lbfrwTES Accepted as read on the motion of P Mylred R Taylor BUSINESS ARISING Raised during other business PRESIDENT'S REPORT 1 have very much pleasure in presenting my second presidential report to this annual meeting of the Australian Veterinary Historical Society. -

Fears of Japanese Aggression in Wool Trade 25 July 2013

Fears of Japanese aggression in wool trade 25 July 2013 Mongolia. The program got off to a bit of a rocky start, however, with claims that some of the sheep from the first shipments of Merinos were eaten by the locals, but it carried on well into the 1940s," he said. Dr Boyd said fear of the project ebbed and flowed throughout the decade. In the first years of the 1930s, the Australian Government went so far as to impose a trade embargo on the export of Merino rams, which led the Japanese to source the animals from South Africa and the United States. Tensions lessened in the mid-1930s due to two on- the-ground investigations. A Murdoch University researcher has uncovered a "In 1934, Sydney Morning Herald journalist Frederic little known nugget of Australian history about a Morley Cutlack took part in the Latham Mission to Japanese push to challenge the nation's wool Asia and looked more closely into the program, dominance in the early 20th century. reporting that it was unlikely to succeed," Dr Boyd said. Dr James Boyd of Murdoch University's Asia Research Centre said he became curious about "A year later, Ian Clunies Ross, who would become Japanese plans to crossbreed a Merino sheep with one of the CSIRO's early directors, was sent by the a hearty Mongolian breed during the 1930s after New South Wales Graziers' Association to do an being asked about the story at a conference. 'expert survey' and came up with similar conclusions. "Out of pure curiosity, I typed the words Mongolia, Japan, Australia and sheep into the newspaper "Still, the story continued to be a source of public archives for the 1930s. -

The Life and Times of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1 FROM FARMBOY TO SUPERSTAR: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REMARKABLE ALF POLLARD John S. Croucher B.A. (Hons) (Macq) MSc PhD (Minn) PhD (Macq) PhD (Hon) (DWU) FRSA FAustMS A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2014 2 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 12 August 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Alf Pollard’s contribution to the business history of Australia is as yet unwritten—both as a biography of the man himself, but also his singular, albeit often quiet, achievements. He helped to shape the business world in which he operated and, in parallel, made outstanding contributions to Australian society. Cultural deprivation theory tells us that people who are working class have themselves to blame for the failure of their children in education1 and Alf was certainly from a low socio-economic, indeed extremely poor, family. He fitted such a child to the letter, although he later turned out to be an outstanding counter-example despite having no ‘built-in’ advantage as he not been socialised in a dominant wealthy culture. -

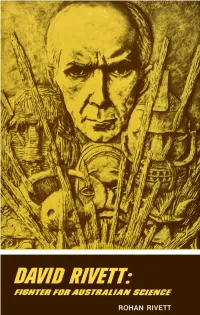

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Biotech Daily Home

Biotech Daily Thursday May 16, 2013 Daily news on ASX-listed biotechnology companies * ASX DOWN, BIOTECH EVEN: - GENETIC TECHNOLOGIES UP 19%, STARPHARMA DOWN 6% * WEHI STUDY FINDS MALARIA PARASITES ‘TALK’ TO EACH OTHER * BIONOMICS, CRC ‘CTx-0357927 INHIBITS MELANOMA TUMORS IN MICE’ * AUSTRALIA ALLOWS BONE LEXCICON PATENT * ANGELINA JOLIE PUMPS GENETIC TECHNOLOGIES 33% * UP TO 15% OF EGM VOTES OPPOSE PRIMA SHORTFALL SHARES * CELLESTIS FOUR WIN ATSE CLUNIES ROSS AWARDS MARKET REPORT The Australian stock market fell 0.5 percent on Thursday May 16, 2013, with the S&P ASX 200 down 26.0 points to 5,165.7 points. Fourteen of the Biotech Daily Top 40 stocks were up, 15 fell, four traded unchanged and seven were untraded. All three Big Caps were down. Genetic Technologies was the best, climbing as much as 33 percent to 10.5 cents, before closing up 1.5 cents or 19.0 percent at 9.4 cents with 3.85 million shares traded, followed by Impedimed up 14.3 percent to eight cents with 505,118 shares traded and Antisense up 11.1 percent to one cent with 1.55 million shares traded. Allied Health, Circadian and Neuren climbed more than eight percent; Alchemia and Phylogica were up more than five percent; Phosphagenics was up four percent; Sirtex was up 3.4 percent; with Anteo, Avita, Nanosonics and Osprey up more than one percent. Starpharma led the falls, down 5.5 cents or 6.2 percent to 83.5 cents, with 543,015 shares traded. Prana fell 4.35 percent; Cellmid, Optiscan, Patrys and Pharmaxis were down more than three percent; Clinuvel, Cochlear, CSL, GI Dynamics, Living Cell and Mesoblast shed more than two percent; Acrux, Prima, Resmed and Viralytics were down more than one percent; with Medical Developments and QRX down by less that one percent. -

Comparison of Host Cell Gene Expression in Cowpox, Monkeypox Or Vaccinia Virus-Infected Cells Reveals Virus-Specific Regulation

Bourquain et al. Virology Journal 2013, 10:61 http://www.virologyj.com/content/10/1/61 RESEARCH Open Access Comparison of host cell gene expression in cowpox, monkeypox or vaccinia virus-infected cells reveals virus-specific regulation of immune response genes Daniel Bourquain1†, Piotr Wojtek Dabrowski1,2† and Andreas Nitsche1* Abstract Background: Animal-borne orthopoxviruses, like monkeypox, vaccinia and the closely related cowpox virus, are all capable of causing zoonotic infections in humans, representing a potential threat to human health. The disease caused by each virus differs in terms of symptoms and severity, but little is yet know about the reasons for these varying phenotypes. They may be explained by the unique repertoire of immune and host cell modulating factors encoded by each virus. In this study, we analysed the specific modulation of the host cell’s gene expression profile by cowpox, monkeypox and vaccinia virus infection. We aimed to identify mechanisms that are either common to orthopoxvirus infection or specific to certain orthopoxvirus species, allowing a more detailed description of differences in virus-host cell interactions between individual orthopoxviruses. To this end, we analysed changes in host cell gene expression of HeLa cells in response to infection with cowpox, monkeypox and vaccinia virus, using whole-genome gene expression microarrays, and compared these to each other and to non-infected cells. Results: Despite a dominating non-responsiveness of cellular transcription towards orthopoxvirus infection, we could identify several clusters of infection-modulated genes. These clusters are either commonly regulated by orthopoxvirus infection or are uniquely regulated by infection with a specific orthopoxvirus, with major differences being observed in immune response genes. -

125 Years of Women in Medicine

STRENGTH of MIND 125 Years of Women in Medicine Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne Kathleen Roberts Marjorie Thompson Margaret Ruth Sandland Muriel Denise Sturtevant Mary Jocelyn Gorman Fiona Kathleen Judd Ruth Geraldine Vine Arlene Chan Lilian Mary Johnstone Veda Margaret Chang Marli Ann Watt Jennifer Maree Wheelahan Min-Xia Wang Mary Louise Loughnan Alexandra Sophie Clinch Kate Suzannah Stone Bronwyn Melissa Dunbar King Nicole Claire Robins-Browne Davorka Anna Hemetek MaiAnh Hoang Nguyen Elissa Stafford Trisha Michelle Prentice Elizabeth Anne McCarthy Fay Audrey Elizabeth Williams Stephanie Lorraine Tasker Joyce Ellen Taylor Wendy Anne Hayes Veronika Marie Kirchner Jillian Louise Webster Catherine Seut Yhoke Choong Eva Kipen Sew Kee Chang Merryn Lee Wild Guineva Joan Protheroe Wilson Tamara Gitanjali Weerasinghe Shiau Tween Low Pieta Louise Collins Lin-Lin Su Bee Ngo Lau Katherine Adele Scott Man Yuk Ho Minh Ha Nguyen Alexandra Stanislavsky Sally Lynette Quill Ellisa Ann McFarlane Helen Wodak Julia Taub 1971 Mary Louise Holland Daina Jolanta Kirkland Judith Mary Williams Monica Esther Cooper Sara Kremer Min Li Chong Debra Anne Wilson Anita Estelle Wluka Julie Nayleen Whitehead Helen Maroulis Megan Ann Cooney Jane Rosita Tam Cynthia Siu Wai Lau Christine Sierakowski Ingrid Ruth Horner Gaurie Palnitkar Kate Amanda Stanton Nomathemba Raphaka Sarah Louise McGuinness Mary Elizabeth Xipell Elizabeth Ann Tomlinson Adrienne Ila Elizabeth Anderson Anne Margeret Howard Esther Maria Langenegger Jean Lee Woo Debra Anne Crouch Shanti -

Marrickville Heritage Society

MARRICKVILLE HERITAGE SOCIETY Covering Dulwich Hill, Enmore, Lewisham, Marrickville, Petersham, St Peters, Stanmore Sydenham, Tempe & parts of Newtown, Camperdown & Hurlstone Park OUR NEXT MEETING DEMOLITION OF SYDENHAM? A WALK AROUND OLD NEWTOWN See Naples and die perhaps, but see Sydenham before it is little more than a railway station. LED BY BRUCE BASKERVILLE Whilst we as a Society take great pains to save Saturday September 23, 10.15 am one building or even a feature of it, here we have the heart of an entire suburb likely to be removed Meet at corner of Wilson Street and Erskineville from our midst forever. The acquisition area Road, Newtown (down from post office). Walk consists of 112 houses in these 40 ANEE zone will commence at 10.30 am heading along Wilson Sydenham streets - Park Road, Railway Road, Street and terminating in Newtown Square about Reilly Lane, George Street, Henry Street, Rowe 12.30 pm. Cost $2 includes booklet. Street and Unwins Bridge Road. So far 40-50 Highlights will include - Newtown's second houses have been bought by the Commonwealth railway station...Vernon's 1892 Anglo-Dutch post Department of Administrative Services (DAS) office... High Hat Cafe {19^0s)...Alba the old 1888 and boarded up, and a further score are about to Oddfellows Hall.. .Henry Henninges' Bakery - the be acquired. An additional 40-50 are earmarked. popular baker...the rabbi, the reverend & the kosher Many residents in the acquisition area have spent butchery...Eliza Donnithorne/Miss Haversham most of their lives there and owner-occupancy connection... Vz's Unita Fortior terraces in Georgina amounts to an estimated 80-90%. -

Encyclopedia of Women in Medicine.Pdf

Women in Medicine Women in Medicine An Encyclopedia Laura Lynn Windsor Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2002 by Laura Lynn Windsor All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Windsor, Laura Women in medicine: An encyclopedia / Laura Windsor p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–57607-392-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Women in medicine—Encyclopedias. [DNLM: 1. Physicians, Women—Biography. 2. Physicians, Women—Encyclopedias—English. 3. Health Personnel—Biography. 4. Health Personnel—Encyclopedias—English. 5. Medicine—Biography. 6. Medicine—Encyclopedias—English. 7. Women—Biography. 8. Women—Encyclopedias—English. WZ 13 W766e 2002] I. Title. R692 .W545 2002 610' .82 ' 0922—dc21 2002014339 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America For Mom Contents Foreword, Nancy W. Dickey, M.D., xi Preface and Acknowledgments, xiii Introduction, xvii Women in Medicine Abbott, Maude Elizabeth Seymour, 1 Blanchfield, Florence Aby, 34 Abouchdid, Edma, 3 Bocchi, Dorothea, 35 Acosta Sison, Honoria, 3 Boivin, Marie -

Bulletin No. 6 Issn 1520-3581

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY THE PACIFIC CIRCLE DECEMBER 2000 BULLETIN NO. 6 ISSN 1520-3581 PACIFIC CIRCLE NEW S .............................................................................2 Forthcoming Meetings.................................................. 2 Recent Meetings..........................................................................................3 Publications..................................................................................................6 New Members...............................................................................................6 IUHPS/DHS NEWS ........................................................................................ 8 PACIFIC WATCH....................................................................... 9 CONFERENCE REPORTS............................................................................9 FUTURE CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS........................ 11 PRIZES, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS........................... 13 ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS...........................................................15 BOOK AND JOURNAL NEWS................................................................ 15 BOOK REVIEWS..........................................................................................17 Roy M. MacLeod, ed., The ‘Boffins' o f Botany Bay: Radar at the University o f Sydney, 1939-1945, and Science and the Pacific War: Science and Survival in the Pacific, 1939-1945.................................. 17 David W. Forbes, ed., Hawaiian National Bibliography: 1780-1900. -

Attenuation of B5R Mutants of Rabbitpox Virus in Vivo Is Related

VIROLOGY 233, 118–129 (1997) ARTICLE NO. VY978556 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Attenuation of B5R Mutants of Rabbitpox Virus in Vivo Is Related to Impaired Growth provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector and Not an Enhanced Host Inflammatory Response Richard J. Stern,* James P. Thompson,† and R. W. Moyer*,1 *Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, Florida 32610-0266; and †Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Gainesville, Florida 32610-0216 Received December 23, 1996; accepted March 21, 1997 The rabbitpox virus (RPV) B5R protein, synthesized late in infection, is found as a 45-kDa membrane-associated protein of the envelope of infectious extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) and as a 38-kDa protein secreted from the cell by a process independent of morphogenesis. The protein is not found associated with intracellular mature virus (IMV). Deletion of the gene attenuates the virus (RPVDB5R) in animals (mice and rabbits), has relatively little effect on formation of IMV, prevents EEV formation in some but not all cells, and leads to a reduced host range. Analysis of the sequence of the protein suggests relatedness to factor H of the complement cascade. Collectively, these observations suggest that attenuation of the virus in vivo could be linked to an inhibition of the inflammatory response, a deficiency in growth, or both. In this report we have analyzed the behavior of RPVDB5R in infected mice and rabbits and conclude that attenuation of the mutant virus likely results from simple failure to grow within the infected animal and that the inflammatory response probably contributes little to the observed attenuation. -

Emeritus Professor Robert (Bob) Reid, One of Australia's Outstanding Agricultural Scientists, Died on 23 September, 1996 in Canberra at the Age of 75

ROBERT LOVELL REID BScAgr(Sydney), PhD(Cantab), FASAP, FAIAS Emeritus Professor Robert (Bob) Reid, one of Australia's outstanding agricultural scientists, died on 23 September, 1996 in Canberra at the age of 75. He was born on 11 April 1921, in Melbourne, but moved with his family when seven years old to Sydney. He was educated at Fort Street High School and on leaving took a year off before deciding to study for a Bachelor of Science degree at the University of Sydney. He specialised in agricultural chemistry and graduated in 1944 with first class honours and was awarded the University medal. He was immediately recruited by the CSIRO to join the famous McMaster laboratories in the University of Sydney. His exceptional talents were recognised by the award, in 1946, of the Thomas Lawrence Powlett Scholarship to read for a PhD degree at King's College, Cambridge, England. While at McMaster he met and married his first wife, Catherine, and their honeymoon was a trip up the New South Wales coast on a tandem bicycle. A more exciting journey was to follow, on one of the first passenger ships to sail, post war, to the UK. While there he pursued, with exceeding diligence, two years of intensive study into the intermediary metabolism of sheep under Professor Sir Joseph Barcroft and as a result of collaboration with two other eminent ruminant biochemists/physiologists, Phillipson and Elsden, produced a distinguished PhD thesis and several scientific papers. On returning to Sydney, he found himself with a dual role: as a lecturer in the University and as a research scientist at McMaster.