Brown Dwarf Disks with Herschel: Linking Far-Infrared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XIII Publications, Presentations

XIII Publications, Presentations 1. Refereed Publications E., Kawamura, A., Nguyen Luong, Q., Sanhueza, P., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: First Results from Aasi, J., et al. including Fujimoto, M.-K., Hayama, K., Kawamura, High Angular Resolution Observations toward the HL Tau Region, S., Mori, T., Nishida, E., Nishizawa, A.: 2015, Characterization of ApJ, 808, L3. the LIGO detectors during their sixth science run, Classical Quantum ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravity, 32, 115012. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Ao, Y., Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Hatsukade, B., Matsuda, Y., Iono, D., Kurono, Y.: 2015, The 2014 Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Astrophysical Implications ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Observations of the Strongly of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914, ApJ, 818, L22. Lensed Submillimeter Galaxy HATLAS J090311.6+003906 at z = Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific 3.042, ApJ, 808, L4. Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, Observation of ALMA Partnership, et al. including Asaki, Y., Hirota, A., Nakanishi, Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger, Phys. Rev. K., Espada, D., Kameno, S., Sawada, T., Takahashi, S., Kurono, Lett., 116, 061102. Y., Tatematsu, K.: 2015, The 2014 ALMA Long Baseline Campaign: Abbott, B. P., et al. including Flaminio, R., LIGO Scientific Observations of Asteroid 3 Juno at 60 Kilometer Resolution, ApJ, Collaboration, Virgo Collaboration: 2016, GW150914: Implications 808, L2. for the Stochastic Gravitational-Wave Background from Binary Black Alonso-Herrero, A., et al. including Imanishi, M.: 2016, A mid-infrared Holes, Phys. -

Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020

Dr. Eric E. Mamajek Curriculum Vitae - 24 March 2020 Jet Propulsion Laboratory Phone: (818) 354-2153 4800 Oak Grove Drive FAX: (818) 393-4950 MS 321-162 [email protected] Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 https://science.jpl.nasa.gov/people/Mamajek/ Positions 2020- Discipline Program Manager - Exoplanets, Astro. & Physics Directorate, JPL/Caltech 2016- Deputy Program Chief Scientist, NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program, JPL/Caltech 2017- Professor of Physics & Astronomy (Research), University of Rochester 2016-2017 Visiting Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2016 Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2013-2016 Associate Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester 2011-2012 Associate Astronomer, NOAO, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 2008-2013 Assistant Professor, Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester (on leave 2011-2012) 2004-2008 Clay Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics 2000-2004 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1999-2000 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Arizona, Astronomy 1998-1999 J. William Fulbright Fellow, Australia, ADFA/UNSW School of Physics Languages English (native), Spanish (advanced) Education 2004 Ph.D. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2001 M.S. The University of Arizona, Astronomy 2000 M.Sc. The University of New South Wales, ADFA, Physics 1998 B.S. The Pennsylvania State University, Astronomy & Astrophysics, Physics 1993 H.S. Bethel Park High School Research Interests Formation and Evolution -

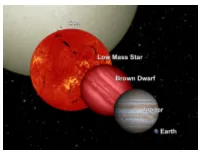

Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R

Types of Stars Spectral Classifications: Based on the luminosity and effective temperature , the stars are categorized depending upon their positions in the HR diagram. Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R Diagram) : 1. The H-R Diagram is a graphical tool that astronomers use to classify stars according to their luminosity (i.e. brightness), spectral type, color, temperature and evolutionary stage. 2. HR diagram is a plot of luminosity of stars versus its effective temperature. 3. Most of the stars occupy the region in the diagram along the line called the main sequence. During that stage stars are fusing hydrogen in their cores. Various Types of Stars Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Brown dwarfs are sub-stellar objects After a star like the sun exhausts its nuclear that are not massive enough to sustain fuel, it loses its outer layer as a "planetary nuclear fusion processes. nebula" and leaves behind the remnant "white Since, comparatively they are very cold dwarf" core. objects, it is difficult to detect them. Stars with initial masses Now there are ongoing efforts to study M < 8Msun will end as white dwarfs. them in infrared wavelengths. A typical white dwarf is about the size of the This picture shows a brown dwarf around Earth. a star HD3651 located 36Ly away in It is very dense and hot. A spoonful of white constellation of Pisces. dwarf material on Earth would weigh as much as First directly detected Brown Dwarf HD 3651B. few tons. Image by: ESO The image is of Helix nebula towards constellation of Aquarius hosts a White Dwarf Helix Nebula 6500Ly away. -

The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459

Whitworth et al.: The Formation of Brown Dwarfs 459 The Formation of Brown Dwarfs: Theory Anthony Whitworth Cardiff University Matthew R. Bate University of Exeter Åke Nordlund University of Copenhagen Bo Reipurth University of Hawaii Hans Zinnecker Astrophysikalisches Institut, Potsdam We review five mechanisms for forming brown dwarfs: (1) turbulent fragmentation of molec- ular clouds, producing very-low-mass prestellar cores by shock compression; (2) collapse and fragmentation of more massive prestellar cores; (3) disk fragmentation; (4) premature ejection of protostellar embryos from their natal cores; and (5) photoerosion of pre-existing cores over- run by HII regions. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Their relative importance probably depends on environment, and should be judged by their ability to reproduce the brown dwarf IMF, the distribution and kinematics of newly formed brown dwarfs, the binary statis- tics of brown dwarfs, the ability of brown dwarfs to retain disks, and hence their ability to sustain accretion and outflows. This will require more sophisticated numerical modeling than is presently possible, in particular more realistic initial conditions and more realistic treatments of radiation transport, angular momentum transport, and magnetic fields. We discuss the mini- mum mass for brown dwarfs, and how brown dwarfs should be distinguished from planets. 1. INTRODUCTION form a smooth continuum with those of low-mass H-burn- ing stars. Understanding how brown dwarfs form is there- The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed on the- fore the key to understanding what determines the minimum oretical grounds by Kumar (1963) and Hayashi and Nakano mass for star formation. In section 3 we review the basic (1963). -

Reionization the End of the Universe

Reionization The End of the Universe How will the Universe end? Is this the only Universe? What, if anything, will exist after the Universe ends? Universe started out very hot (Big Bang), then expanded: Some say the world will end in fire, Some say in ice. From what I’ve tasted of desire I hold with those who favor fire. But if I had to perish twice, I think I know enough of hate To know that for destruction ice is also great And would suffice. How it ends depends on the geometry of the Universe: Robert Frost 2) More like a saddle than a sphere, with curvature in the opposite The Geometry of Curved Space sense in different dimensions: "negative" curvature. Possibilities: Sum of the 1) Space curves back on itself (like a sphere). "Positive" curvature. Angles < 180 Sum of the Angles > 180 3) A more familiar flat geometry. Sum of the Angles = 180 1 The Geometry of the Universe determines its fate Case 1: high density Universe, spacetime is positively curved Result is “Big Crunch” Fire The Five Ages of the Universe Cases 2 or 3: open Universe (flat or negatively curved) 1) The Primordial Era 2) The Stelliferous Era 3) The Degenerate Era 4) The Black Hole Era Current measurements favor an open Universe 5) The Dark Era Result is infinite expansion Ice 1. The Primordial Era: 10-50 - 105 y The Early Universe Inflation Something triggers the Creation of the Universe at t=0 A problem with microwave background: Microwave background reaches us from all directions. -

EVOLVED STARS a Vision of the Future Astron

PUBLISHED: 04 JANUARY 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0021 research highlights EVOLVED STARS A vision of the future Astron. Astrophys. 596, A92 (2016) Loop Plume A B EDPS A nearby red giant star potentially hosts a planet with a mass of up to 12 times that of Jupiter. L2 Puppis, a solar analogue five billion years more evolved than the Sun, could give a hint to the future of the Solar System’s planets. Using ALMA, Pierre Kervella has observed L2 Puppis in molecular lines and continuum emission, finding a secondary source that is roughly 2 au away from the primary. This secondary source could be a giant planet or, alternatively, a brown dwarf as massive as 28 Jupiter masses. Further observations in ALMA bands 9 or 10 (λ ≈ 0.3–0.5 mm) can help to constrain the companion’s mass. If confirmed as a planet, it would be the first planet around an asymptotic giant branch star. L2 Puppis (A in the figure) is encircled by an edge-on circumstellar dust disk (inner disk shown in blue; surrounding dust in orange), which raises the question of whether the companion body is pre-existing, or if it has formed recently due to accretion processes within the disk. If pre-existing, the putative planet would have had an orbit similar in extent to that of Mars. Evolutionary models show that eventually this planet will be pulled inside the convective envelope of L2 Puppis by tidal forces. The companion’s interaction with the star’s circumstellar disk has invoked pronounced features above the disk: an extended loop of warm dusty material, and a visible plume, potentially launched by accretion onto a disk of material around the planet itself (B in the figure). -

A Review on Substellar Objects Below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs Or What?

geosciences Review A Review on Substellar Objects below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs or What? José A. Caballero Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n, E-28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 10 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: “Free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects” are isolated bodies of a few Jupiter masses found in very young open clusters and associations, nearby young moving groups, and in the immediate vicinity of the Sun. They are neither brown dwarfs nor planets. In this paper, their nomenclature, history of discovery, sites of detection, formation mechanisms, and future directions of research are reviewed. Most free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects share the same formation mechanism as low-mass stars and brown dwarfs, but there are still a few caveats, such as the value of the opacity mass limit, the minimum mass at which an isolated body can form via turbulent fragmentation from a cloud. The least massive free-floating substellar objects found to date have masses of about 0.004 Msol, but current and future surveys should aim at breaking this record. For that, we may need LSST, Euclid and WFIRST. Keywords: planetary systems; stars: brown dwarfs; stars: low mass; galaxy: solar neighborhood; galaxy: open clusters and associations 1. Introduction I can’t answer why (I’m not a gangstar) But I can tell you how (I’m not a flam star) We were born upside-down (I’m a star’s star) Born the wrong way ’round (I’m not a white star) I’m a blackstar, I’m not a gangstar I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar I’m not a pornstar, I’m not a wandering star I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar Blackstar, F (2016), David Bowie The tenth star of George van Biesbroeck’s catalogue of high, common, proper motion companions, vB 10, was from the end of the Second World War to the early 1980s, and had an entry on the least massive star known [1–3]. -

Can Brown Dwarfs Survive on Close Orbits Around Convective Stars? C

A&A 589, A55 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527100 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics Can brown dwarfs survive on close orbits around convective stars? C. Damiani1 and R. F. Díaz2 1 Université Paris-Sud, CNRS, Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, UMR8617, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Observatoire astronomique de l’Université de Genève, 51 ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] Received 1 August 2015 / Accepted 23 February 2016 ABSTRACT Context. The mass range of brown dwarfs extends across the planetary domain to stellar objects. There is a relative paucity of brown dwarfs companions around FGKM-type stars compared to exoplanets for orbital periods of less than a few years, but most of the short-period brown dwarf companions that are fully characterised by transits and radial velocities are found around F-type stars. Aims. We examine the hypothesis that brown dwarf companions could not survive on close orbit around stars with important convec- tive envelopes because the tides and angular momentum loss, the result of magnetic braking, would lead to a rapid orbital decay with the companion being quickly engulfed. Methods. We use a classical Skumanich-type braking law and constant time-lag tidal theory to assess the characteristic timescale for orbital decay for the brown dwarf mass range as a function of the host properties. Results. We find that F-type stars may host massive companions for a significantly longer time than G-type stars for a given orbital period, which may explain the paucity of G-type hosts for brown dwarfs with an orbital period less than five days. -

The Coolest Brown Dwarfs

ClassY - The Coolest Brown Dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3 – T9/Y0 - first class Y, 30 light-years distance, Temp 620K, Mass 15-30 M_Jup WISE 0855−0714 – Y2 - coolest at Temp ~ 250K, 7.3 light-years distance, Mass 3-10 M_Jup ClassY - The Coolest Brown Dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3 – T9/Y0 - first class Y, 30 light-years distance, Temp 620K, Mass 15-30 M_Jup WISE 0855−0714 – Y2 - coolest at Temp ~ 250K, 7.3 light-years distance, Mass 3-10 M_Jup Why are all brown dwarf stars about the same size, even if the mass ranges from 10-500 M_Jup? Stellar evolution so far Different energy sources during different stages in the star's evolution Protostar phase (KH contraction) MS phase H->He RGB phase (shell H->He) And remember: more massive stars evolve faster during all stages What is this Plot Showing? globular cluster Announcements • Today – More low mass stellar evolution • Thursday – High mass stellar evolution and HW#4 is due • Tuesday Feb 25 – Review • Thursday Feb 27 – Exam#1 Intrinsic variability • Those that vary in brightness as a result of conditions within the star itself. • Found in the instability strip. Any star within these portions of the H-R diagram will become unstable to pulsations. • The different regions produce different kinds of observed phenomena. • Stars may go through these stages several times during their lives. Cause of pulsations • Stars are variable because they are unstable in one way or another: they lack hydrostatic equilibrium beneath surface. • Miras are not well understood, but other, more periodically varying stars are better understood, like the Cepheids: • The ionization zone of He lies at a distance from the center of the star, close to the surface. -

The Birth and Evolution of Brown Dwarfs

The Birth and Evolution of Brown Dwarfs Tutorial for the CSPF, or should it be CSSF (Center for Stellar and Substellar Formation)? Eduardo L. Martin, IfA Outline • Basic definitions • Scenarios of Brown Dwarf Formation • Brown Dwarfs in Star Formation Regions • Brown Dwarfs around Stars and Brown Dwarfs • Final Remarks KumarKumar 1963; 1963; D’Antona D’Antona & & Mazzitelli Mazzitelli 1995; 1995; Stevenson Stevenson 1991, 1991, Chabrier Chabrier & & Baraffe Baraffe 2000 2000 Mass • A brown dwarf is defined primarily by its mass, irrespective of how it forms. • The low-mass limit of a star, and the high-mass limit of a brown dwarf, correspond to the minimum mass for stable Hydrogen burning. • The HBMM depends on chemical composition and rotation. For solar abundances and no rotation the HBMM=0.075MSun=79MJupiter. • The lower limit of a brown dwarf mass could be at the DBMM=0.012MSun=13MJupiter. SaumonSaumon et et al. al. 1996 1996 Central Temperature • The central temperature of brown dwarfs ceases to increase when electron degeneracy becomes dominant. Further contraction induces cooling rather than heating. • The LiBMM is at 0.06MSun • Brown dwarfs can have unstable nuclear reactions. Radius • The radii of brown dwarfs is dominated by the EOS (classical ionic Coulomb pressure + partial degeneracy of e-). • The mass-radius relationship is smooth -1/8 R=R0m . • Brown dwarfs and planets have similar sizes. Thermal Properties • Arrows indicate H2 formation near the atmosphere. Molecular recombination favors convective instability. • Brown dwarfs are ultracool, fully convective, objects. • The temperatures of brown dwarfs can overlap with those of stars and planets. Density • Brown dwarfs and planets (substellar-mass objects) become denser and cooler with time, when degeneracy dominates. -

Chapter 1 a Theoretical and Observational Overview of Brown

Chapter 1 A theoretical and observational overview of brown dwarfs Stars are large spheres of gas composed of 73 % of hydrogen in mass, 25 % of helium, and about 2 % of metals, elements with atomic number larger than two like oxygen, nitrogen, carbon or iron. The core temperature and pressure are high enough to convert hydrogen into helium by the proton-proton cycle of nuclear reaction yielding sufficient energy to prevent the star from gravitational collapse. The increased number of helium atoms yields a decrease of the central pressure and temperature. The inner region is thus compressed under the gravitational pressure which dominates the nuclear pressure. This increase in density generates higher temperatures, making nuclear reactions more efficient. The consequence of this feedback cycle is that a star such as the Sun spend most of its lifetime on the main-sequence. The most important parameter of a star is its mass because it determines its luminosity, ef- fective temperature, radius, and lifetime. The distribution of stars with mass, known as the Initial Mass Function (hereafter IMF), is therefore of prime importance to understand star formation pro- cesses, including the conversion of interstellar matter into stars and back again. A major issue regarding the IMF concerns its universality, i.e. whether the IMF is constant in time, place, and metallicity. When a solar-metallicity star reaches a mass below 0.072 M ¡ (Baraffe et al. 1998), the core temperature and pressure are too low to burn hydrogen stably. Objects below this mass were originally termed “black dwarfs” because the low-luminosity would hamper their detection (Ku- mar 1963). -

Search for Brown-Dwarf Companions of Stars⋆⋆⋆

A&A 525, A95 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015427 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Search for brown-dwarf companions of stars, J. Sahlmann1,2, D. Ségransan1,D.Queloz1,S.Udry1,N.C.Santos3,4, M. Marmier1,M.Mayor1, D. Naef1,F.Pepe1, and S. Zucker5 1 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany 3 Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 4 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Portugal 5 Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel Received 19 July 2010 / Accepted 23 September 2010 ABSTRACT Context. The frequency of brown-dwarf companions in close orbit around Sun-like stars is low compared to the frequency of plane- tary and stellar companions. There is presently no comprehensive explanation of this lack of brown-dwarf companions. Aims. By combining the orbital solutions obtained from stellar radial-velocity curves and Hipparcos astrometric measurements, we attempt to determine the orbit inclinations and therefore the masses of the orbiting companions. By determining the masses of poten- tial brown-dwarf companions, we improve our knowledge of the companion mass-function. Methods. The radial-velocity solutions revealing potential brown-dwarf companions are obtained for stars from the CORALIE and HARPS planet-search surveys or from the literature. The best Keplerian fit to our radial-velocity measurements is found using the Levenberg-Marquardt method.