Trade, War, Privilege and the Path to Matayoshi Kobudo Robert Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kobudo Weapons Rules

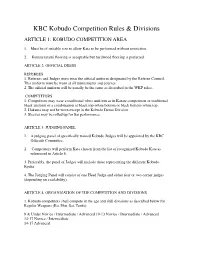

KBC Kobudo Competition Rules & Divisions ARTICLE 1: KOBUDO COMPETITION AREA 1. Must be of suitable size to allow Kata to be performed without restriction. 2. Kumite tatami flooring is acceptable but hardwood flooring is preferred. ARTICLE 2: OFFICIAL DRESS REFEREES 1. Referees and Judges must wear the official uniform designated by the Referee Council. This uniform must be worn at all tournaments and courses. 2. The official uniform will be usually be the same as described in the WKF rules. COMPETITORS 1. Competitors may wear a traditional white uniform as in Karate competition or traditional black uniform or a combination of black top-white bottom or black bottom-white top. 2. Hakama may not be worn except in the Kobudo Demo Division. 3. Sleeves may be rolled up for Sai performance. ARTICLE 3: JUDGING PANEL 1. A judging panel of specifically trained Kobudo Judges will be appointed by the KBC Officials Committee. 2. Competitors will perform Kata chosen from the list of recognized Kobudo Kata as referenced in Article 8. 3. Preferably, the panel of Judges will include those representing the different Kobudo Ryuha 4. The Judging Panel will consist of one Head Judge and either four or two corner judges (depending on availability). ARTICLE 4: ORGANIZATION OF THE COMPETITION AND DIVISIONS 1. Kobudo competitors shall compete in the age and skill divisions as described below for Regular Weapons (Bo, Eku, Sai, Tonfa): 9 & Under Novice / Intermediate / Advanced 10-13 Novice / Intermediate / Advanced 14-17 Novice / Intermediate 14-17 Advanced 18 & Over Novice / Intermediate 18 & Over Advanced 17 & Under Black 18 & Over Black. -

April 2007 Newsletter

December 2018 Newsletter Goju-Ryu Karate-Do Kyokai www.goju.com ________________________________________________________ Obituary: Zachary T. Shepherdson-Barrington Zachary T. Shepherdson-Barrington 25, of Springfield, passed away at 1:22 p.m. on Tuesday, November 27, 2018 at Memorial Medical Center. Zachary was born October 12, 1993 in Springfield, the son of Kim D. Barrington and Rebecca E. Shepherdson. Zachary attended Lincoln Land Community College. He was a former member of The Springfield Goju-Ryu Karate Club where he earned a brown belt in karate. He worked for Target and had worked in retail for several years. He also worked as a driver for Uber. He enjoyed game night with his friends and working on the computer. He was preceded in death by his paternal grandparents, James and Fern Gilbert; maternal grandparents, Carol J. Karlovsky and Harold T. Shepherdson; seven uncles, including Mark Shepherdson; and aunt, Carolyn Norbutt. He is survived by his father Kim D. Barrington (wife, Patricia M. Ballweg); mother, Rebecca E. Shepherdson of Springfield; half-brother, Derek Embree of Girard; and several aunts, uncles, and cousins. Cremation will be accorded by Butler Cremation Tribute Center prior to ceremonies . Memorial Gathering: Family will receive friends from 10:00 to 10:45 a.m. on Tuesday, December 4, 2018 at First Church of the Nazarene, 5200 S. 6th St., Springfield. Memorial Ceremony: 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, December 4, 2018 at First Church of the Nazarene, with Pastor Fred Prince and Pastor Jay Bush officiating. Memorial contributions may be made to the American Cancer Society, 675 E. Linton, Springfield, IL 62703. -

©Northern Karate Schools 2017

©Northern Karate Schools 2017 NORTHERN KARATE SCHOOLS MASTERS GUIDE – CONTENTS Overview Essay: Four Black Belt Levels and the Title “Sensei” (Hanshi Cezar Borkowski, Founder, Northern Karate Schools) Book Excerpt: History and Traditions of Okinawan Martial Arts (Master Hokama Tetsuhiro) Essay: What is Kata (Kyoshi Michael Walsh) Northern Karate Schools’ Black Belt Kata Requirements Northern Karate Schools’ Kamisa (Martial Family Tree) Article: The Evolution of Ryu Kyu Kobudo (Hanshi Cezar Borkowski, ed. Kyoshi Marion Manzo) Northern Karate Schools’ Black Belt Kobudo Requirements Northern Karate Schools’ Additional Black Belt Requirements ©Northern Karate Schools 2017 NORTHERN KARATE SCHOOLS’ MASTERS CLUB - OVERVIEW In response to unprecedented demand and high retention rates among senior students, Northern Karate Schools Masters Club, an advanced, evolving program, was launched in 1993 by Hanshi Borkowski. Your enrolment in this unique program is a testament to your continued commitment to achieving Black Belt excellence and your devotion to realising personal best through martial arts study. This Masters Club Student Guide details requirements for Shodan to Rokudan students. It contains select articles, essays and book excerpts as well as other information aimed at broadening your understanding of the history, culture and philosophy of the martial arts. Tradition is not to preserve the ashes but to pass on the flame. Gustav Mahler ©Northern Karate Schools 2017 FOUR BLACK BELT LEVELS AND THE TITLE “SENSEI” by Hanshi Cezar Borkowski Karate students and instructors often confuse the terms Black Belt and Sensei. Sensei is commonly used to mean teacher however, the literal translation of the word is one who has gone before. Quite simply, that means an instructor who has experienced certain things and shares what he/she has learned with others - a tour guide along the road of martial arts life. -

2010 – US Martial Arts Hall of Fame Inductees

Year 2010 – US Martial Arts Hall of Fame Inductees Alaska Annette Hannah……………………………………………...Female Instructor of the year Ms. Hannah is a 2nd degree black belt in Shaolin Kempo. She has also studied Tae kwon do, and is a member of ISSKA. Ms. Hannah has received two appreciation awards from the U.S. Army, and numerous sparring trophies. She is also proud to provide service to help the U.S. soldiers and their families that sacrifice to keep this country safe and risk their lives for all of us. James Grady …………………………………………………………………………….Master Mr. Grady is a member of The Alaska Martial Arts Association and all Japan Karate Do Renbukai. Mr. Grady is a 6th Dan in Renbukan California William Aguon Guinto ………………………………………………………..Grandmaster Mr. Guinto has studied the art for 40 years he is the owner and founder of Brown Dragon Kenpo. He has training in the styles of Aiki do, Kyokoshihkai, tae kwon do, and Kenpo. Mr. Guinto is a 10th Grandmaster in Brown Dragon Kenpo Karate and has received awards in Kenpo International Hall of Fame 2007 and Master Hall of Fame Silver Life. He is a member of U.S.A. Martial Arts Alliance and International Martial Arts Alliance. Steven P. Ross ………………………………………………Master Instructor of the year Mr. Ross has received awards in 1986 World Championship, London England, numerous State, Regional and National Championships from 1978 thru 1998, Employee of the Year 2004, and principal for the day at a local high school. He was formerly a member of The US Soo Bahk Do, and Moo Duk Kwan Federation. -

Uechi-Ryu History

Welcome to Rooke School of Karate! Congratulations on your decision to take the challenge towards personal growth and development! Sensei Steven Rooke and the fellow students at the Rooke School of Karate take great pleasure in welcoming you to our school. By becoming a member of our karate school, you will join an organization that takes great pride in our students and the martial arts that we learn. Since the Rooke School of Karate opened in 2006, we have been committed to building and developing our students into the best that they can be. As a student works and trains towards becoming a Black Belt, they will experience challenges, growth, progress and change within our school, as in many other aspects of their lives. We hope that you will find our karate school to be a positive experience that will influence your life and/or that of your child. Our objective here at the Rooke School of Karate is to provide you with a well structured martial arts program in a safe, positive and non-intimidating learning environment that promotes a positive attitude where students will develop their mental strength and physical endurance that will lead to greater confidence and self discipline. We offer a positive approach to a student’s success, creating attainable goals for the students in an environment that makes learning fun. In the beginning, it is always best to focus on developing a strong foundation of skill and understanding of the basic maneuvers and techniques we practice. In addition to getting your body in better shape, you should notice an increase in strength and flexibility along with greater energy and endurance within the first few months. -

Sensei Dometrich Promoted to 9Th Dan, Hanshi Grade

THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE YOSHUKAN KARATE ASSOCIATION Winter 2020 SENSEI DOMETRICH PROMOTED TO 9TH DAN, HANSHI GRADE Sensei Devorah Dometrich, Chief Instructor of the RYU KYU KOBUDO HOZON SHINKOKAI (Okinawan Weapons Preservation Society) has been promoted to 9th Dan, Hanshi (Grand Master grade) by her group of 29 Shibu (Senior Students). Sensei Dometrich has devoted her life to studying and teaching the ancient okinawan weapons comprised of: Bo; Tekko; Nunchaku; Sai; Tonfa; Tinbe; Eku; and Kama. Sensei has developed a large community of senior teachers in three countries and spends a tremendous amount of time each year driving across North America and promoting her art. A consistent visitor to the Yoshukan Karate Association summer camp, Sensei has developed a new group of kobudo Kancho Robertson presenting Sensei Dometrich with a Red Belt on behalf of the Continued on Page 2 Canadian Kobudo students, with Sensei Steve Kabboord hosting KANCHO CORNER IN THIS ISSUE COURAGE 4 Karate Excellence Yoshukan Karate Years ago I was a witness to a purse-snatching. I was sitting in traffic and 5 Association a woman had her purse snatched and began screaming. I quickly parked Tournament and took off after the snatcher. This was in upper Westmount and the man ran down into lower Westmount. Another man on the sidewalk also took 6 Athletes des Jeux du pursuit and he and I were scouring the back alleys of the area looking for Quebec Par Excellence the snatcher. We eventually gave up on the pursuit and walked back to the 7 Multi-Dojo Exam area we started. -

OKINAWA KARATE Meisters Seminar Sonntag, 15. September 2019 In

International Kobudo Camp 2020 16 - 19 April 2020 in Pfreimd, Germany Venue: LUH Landgraf-Ulrich-Halle, Landgraf-Johann-Str. 15, 92536 Pfreimd Instructors: Sensei Jamal Measara, 8. DAN Kobudo Sensei Werner Bachhuber, 4. DAN Kobudo Sensei Oliver Riess, 3. DAN Kobudo Sensei Günther Schmid, 2. DAN Kobudo Enrollment: Online at Werner Bachhuber https://budo-akademie-muenchen.de/terminliste Payment: 300 € for 4 days + 35 € for Farewell Dinner (without drinks) = Total 335 € One day ticket 100 € Welcome Party pay yourself Dear Karate / Kobudoka, GET TOGETHER This is in my intention to have once or twice a year a Kobudo Camp for everyone all over the world. This Kobudo Camp is especially recommended for Instructors of foreign Countries and also for the locals and for every belt rankings (including foreign Countries) WEAPONS This Camp training will be conduted by high ranking black belts including me (Measara) the training consists of Bo, Sai, Nunchaku techniques with (handtowel) (Nunchaku is prohibited in Germany) Tunkwa, Jo, Eku, Nunti, Kama and (Tekko Safety) etc. with Kihon, Katas, Bunkais and Yakusoku Kumite. FRESHING UP This Camp trainings purpose is to get all Kobudo Instructors and students to fresh up with their old techniques, Katas which might have been forgotten or wrongly interpreted or practiced and of course to learn the new weapons and techniques. This will enable all countries doing the same Wazas. PROMOTION TEST Also I intend to have promotion test for persons interested. My intension is to build all intructors who would like to teach this old and art for the next generations. Most of all, this Camp training is to get all Budokas of different nations to know each other and practice and exchange their knowledge and have a wonderful week together. -

International Ryukyu Kobudo Federation

International Ryukyu Kobudo Federation N A T I O E R N T A N L I RYUKYU F E KOBUDO N D O E R A T I Ryukyu Kobudo is the practice of martial arts weapons that developed in the Ryukyu Islands. The Ryukyu Islands are a chain of islands extending southwest from the southern end of Kyushu Island in Japan. Notable islands include Okinawa and Hama Higa Islands. The kata names originate from the Kyushu island or village where they s nd developed, or from the master that is sla u I ky credited with the kata. yu R Okinawa Short History Okinawa is the largest island in the Ryukyu Island chain. Both Japanese and Chinese settlers have been there since around 300 BC. By 1340 AD. three kingdoms exist in the Ryukyu Islands, Hokuzan, Chuzan, and Nazan. These three kingdoms are at war with each other for dominance of the island chain. It is at this time that trade begins with China. In 1393 AD. China sends a large group of people to Okinawa as part of the cultural exchange. Included in this group are monks from the Shaolin Temple. This begins the combination of Shaolin Kung Fu with Okinawan Te. In 1429 AD. The Ryukyu Islands are united under one king. The kingdom prospers due to the trade with all of Asia. In 1447 AD. King Sho Shin bans all weapons from civilians to keep the peace. This is the first “Weaponless Period”. In 1609 AD. the Satsuma clan invades the Ryukyu Islands and captures the King. -

Matayoshi Kobudo, a Brief History and Overview

Creating chances for Matayoshi Kobudo experience A Brief History and Overview Several weeks ago I organised a workout While there are a number of books and numerous articles about reunion for my former and present karate the various unarmed systems of Okinawan martial arts, there is students and the focus of this special workout little quality written material in English about the various armed was on close combat mass attacks. During the workout I slowly worked towards arts of the island. There are a small number of sources looking at a fighting scenario where we ultimately had the performance of various kata, and some on application of these hardly any space to manoeuvre, often standing kata, but there are a dearth of sources that clearly examine the shoulder to shoulder as in a huge packed content and history of any of the island's major weapons systems. crowd of hundreds and where everybody was This article is an attempt to begin to fill some of that gap in the fighting everybody. At its climax people were pushed back in the fighting crowd when they literature by more carefully examining the history and content of escaped the centre of fighting and medicine the Matayoshi kobudo. balls were constantly being thrown in to add another dimension. A scenario with an extre- - Frederick W. Lohse III - mely chaotic and uncontrollable nature. Some of my former students were not familiar with this type of mass attack training where all attacks can be initiated at any time, totally The armed arts of Okinawa have always communal impact. -

Karatekas and Parents

Welcome Karatekas and Parents We now enter the last quarter of our karate year and things are going to get busy. Grading is around the corner as well as our very first club tournament. Please make a note of all the upcoming events as they are all very important. Grading Preparations Please take note that at least 14 classes need to be attended in order to qualify for grading. The finger print system is there for the purpose of clocking in Spring Day 2016 when karateka pitch up for training, just before grading takes place, the records are downloaded from the system in order to Spirits were high this year as our Karatekas came to class dressed in tally up the amount of classes attended, thus we can see who all colours. Cup cakes were given as a treat at the end of training as a attended the correct amount of classes. welcomed surprise. Everyone, Instructors and Students alike enjoyed the change of scene and vibe. So, please make sure karateka clock in every time before classes, Click here for more otherwise it will be assumed that you were absent. We would like everyone to take part in our club tournament, for one event or all. The white belts will be doing an obstacle course and can choose to do free fighting if they wish. We look forward to seeing everyone there. Creche to Dojo Visits If one looks carefully, once a month there are the pitter patter of new little feet running around with the Solis Ortus Minis. These are the the Karate Kids from the 5 creches we are currently teaching at. -

The Shorin-Ryu Shorinkan of Williamsburg

Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg The Shorin-Ryu Karate of Williamsburg Official Student Handbook Student Name: _________________________________________ Do not duplicate 1 Shorin-Ryu of Williamsburg General Information We are glad that you have chosen our school to begin your or your child’s journey in the martial arts. This handbook contains very important information regarding the guidelines and procedures of our school to better inform you of expectations and procedures regarding training. The quality of instruction and the training at our dojo are of the highest reputation and are designed to bring the best out of our students. We teach a code of personal and work ethics that produce citizens of strong physical ability but most importantly of high character. Students are expected to train with the utmost seriousness and always give their maximum physical effort when executing techniques in class. Instructors are always observing and evaluating our students based on their physical improvements but most of all, their development of respect, courtesy and discipline. Practicing karate is very similar to taking music lessons- there are no short cuts. As in music, there are people that possess natural ability and others that have to work harder to reach goals. There are no guarantees in music instruction that say someone will become a professional musician as in karate there are no guarantees that a student will achieve a certain belt. This will fall only on the student and whether they dedicate themselves to the instruction given to them. Our school does not offer quick paths to belts for a price as many commercial schools do. -

Welch's Okinawa Karate-Do

Dear Sensei and Karateka: It is an honor to be hosting our annual Spring National Training Camp here in Williamsburg, Virginia. The format of this camp will follow our previous gasshuku and cover topics of kihon, Shorin-Ryu kata, kobudo, kumite (iri-kumi and sport kumite) and application. This is an outstanding opportunity for students of all styles of Okinawa Karate to train together and we hope this experience will create new friendships. The purpose of a gasshuku is to evaluate and strengthen the skills and curriculum areas of all members and to also create opportunities for karateka to grow. As there are no “spectators” or seniors standing on the sidelines in the dojo on Okinawa, we will hope that every participant will represent themselves, their style and their teacher by training on the floor. It is all too common for individuals to attend camps just to have picture opportunities with famous karate sensei but do very little training. I hope that everyone will push themselves and each other to complete the training with tremendous spirit and effort. We look forward to training with you and sharing knowledge at this special event! If there are any questions or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact me at [email protected] or (757-870- 0311) Camp Director, John Spence, United States Hombu-Cho, Shorin-Ryu Butokukan ジョン スペンス 北米 支部 道場 沖縄空手道小林流武徳館 Shorin-Ryu Karate of Williamsburg Proudly Presents 2017 Spring Training Camp When: May 5, 6, 7, 2017 Where: Matoaka Elementary Gymnasium, 4001 Brick Bat Road, Williamsburg, Virginia 23188 What: Camp classes will consist of kihon, Shorin-Ryu kata, kobudo, kumite (iri-kumi and sport kumite) and application.