Grega Thesis Final Draft No Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

Teachers' Notes the GEORGIANS

Teachers’ Notes THE GEORGIANS (Rooms 9 – 14) Portraits as Historical Evidence These guided discussion notes reflect the way in which the National Portrait Gallery Learning Department works when using portraits as historical sources, with pupils of all ages. As far as possible, pupils are encouraged through questioning to observe in detail and to form their own hypotheses; a small amount of information is fed into the discussion at appropriate points to deepen their observations. These notes therefore consist of a series of questions, with suggested answers; where there is information to add this is shown in a box. The questions, perhaps slightly rephrased, would be suitable for pupils at both primary and secondary level; what will differ is the sophistication of the answers. The information will need rephrasing for younger pupils and it may be necessary to probe by adding extra questions to get the full interpretation of the picture. Please note we cannot guarantee that all of the portraits in these notes will be on display at the time of your visit. Please see www.npg.org.uk/learning/digital for these and other online resources. Other guided discussions in this series of online Teachers’ Notes include: Tudors Stuarts Regency Victorians Twentieth Century and Contemporary These guided discussions can be used either when visiting the Gallery on a self-directed visit or in the classroom using images from the Gallery’s website, www.npg.org.uk/collections. All self directed visits to the Gallery must be booked in advance by telephone on 020 7312 2483. If you wish to support your visit with the use of Teachers’ Notes please book in advance, stating which notes you wish to use in order for us to check that the appropriate Gallery rooms are available at the time of your visit. -

Scottish Art: Then and Now

Scottish Art: Then and Now by Clarisse Godard-Desmarest “Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now”, an exhibition presented in Edinburgh by the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture tells the story of collecting Scottish art. Mixing historic and contemporary works, it reveals the role played by the Academy in championing the cause of visual arts in Scotland. Reviewed: Tom Normand, ed., Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now Collected by the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Edinburgh, The Royal Scottish Academy, 2017, 248 p. The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) and the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) have collaborated to present a survey of collecting by the academy since its formation in 1826 as the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Ages of Wonder: Scotland’s Art 1540 to Now (4 November 2017-7 January 2018) is curated by RSA President Arthur Watson, RSA Collections Curator Sandy Wood and Honorary Academician Tom Normand. It has spawned a catalogue as well as a volume of fourteen essays, both bearing the same title as the exhibition. The essay collection, edited by Tom Normand, includes chapters on the history of the RSA collections, the buildings on the Mound, artistic discourse in the nineteenth century, teaching at the academy, and Normand’s “James Guthrie and the Invention of the Modern Academy” (pp. 117–34), on the early, complex history of the RSA. Contributors include Duncan Macmillan, John Lowrey, William Brotherston, John Morrison, Helen Smailes, James Holloway, Joanna Soden, Alexander Moffat, Iain Gale, Sandy Wood, and Arthur Watson. -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Jon Craig and William Allan the Concept of Tax Expenditures Was De

FISCAL TRANSPARENCY, TAX EXPENDITURES, AND BUDGET PROCESSES: AN 1 INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE Jon Craig and William Allan The concept of tax expenditures was developed in the United States and Germany in the 1960s and spread to a significant number of OECD countries in the 1980s. There has been a renewed international interest of late, with Brazil and Korea and a few non-OECD members adopting the practice of reporting tax expenditures to the public. This paper outlines the work being initiated through the IMF Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency to promote the tax expenditure concept as a standard feature of national budget presentation. A. Fiscal Transparency and Tax Expenditures The international community has sought to promote more openness about the conduct of fiscal and other policies in member countries. To that end, the Fund staff developed a Code of Good Practices in Fiscal Transparency that was initially approved by the Executive Board of the Fund in April 1998, and a slightly modified version was approved by the Board on March 26, 2001. The fiscal transparency code defines a set of specific principles, and, under each of these principles, a set of operational good practices.2 Member countries implement the code on a voluntary basis. Countries indicate their commitment to transparency by participating in a Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC), which involves, first, consideration of their practices against a self-assessment questionnaire and then an assessment by IMF staff against each of the good practices defined in the code, including suggestions of priority areas to improve transparency. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3. -

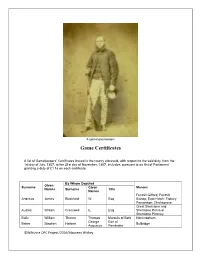

Game Certificates

A typical gamekeeper Game Certificates A list of Gamekeepers’ Certificates issued in the county aforesaid, with respect to the said duty, from the 1st day of July, 1807, to the 21st day of November, 1807, inclusive, pursuant to an Act of Parliament granting a duty of £1 1s on each certificate. By Whom Deputed Given Surname Given Manors Names Surname Title Names Fonthill Gifford; Fonthill Andrews James Blackford W. Esq. Bishop; East Hatch; Tisbury Parsonage; Chicksgrove Great Sherstone and Austen William Cresswell E. Esq. Sherstone Parva or Sherstone Pinkney Baily William Thynne Thomas Marquis of Bath Horningsham George Earl of Baker Stephen Herbert Bulbridge Augustus Pembroke ©Wiltshire OPC Project/2016/Maureen Withey Barnes William Wyndham W. Esq. Teffont Evias Littlecot with Rudge; Chilton Foliat with Soley; North Standen with Oakhill; & Charnham Street; with liberty Popham E. W. L. Esq. to kill game within the said manors of Littlecot with Rudge and Chilton Foliat with Soley Goddard A. Esq. Wither L. B. Esq. Northey W. Esq. Barrett Joseph Brudenell- Thomas Earl of Ailesbury Bruce Rev., D.D., Popham E. Clerk Froxfield Vilet T. G. Rev., Ll.d., Clerk Rt. Hon., Bruce C. B. commonly called Lord Bruce Goddard E. Rev., Clerk Michell T. Esq. Warneford F. Esq. North Tidworth; otherwise Batchelor Henry Poore E. Dyke Esq. Tidworth Zouch; and Figheldean Scrope W. Esq. Castle Coomb Beak William Sevington Vince H. C. Esq. Leigh-de-la-Mare Beck Thomas Astley F .D. Esq Boreham Pewsey; within the tithings of Beck William Astley F. D. Esq. Southcott and Kepnell Bennett John Williams S. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography The bibliography is divided into two parts: a schedule of general texts 2 the politics of portraiture c. 1660–75 selected readings for those who wish to explore the back- arnold, dana and peters corbett, david, eds., barber, tabitha, Mary Beale (1632/3–1699): Portrait ground of developments described in the book – both A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present, of a Seventeenth-Century Painter, Her Family and as a whole and chapter by chapter – followed by a much Chichester, 2013. Her Studio, exhibition catalogue, Geffrye Museum, longer list that is intended to function as an introductory barrell, john, The Political Theory of Painting from London, 1999. guide to research in the field of British two-dimensional Reynolds to Hazlitt: ‘The Body of the Public’, New coombs, katherine, The Portrait Miniature in art between the Restoration and the Battle of Waterloo. Haven and London, 1986. England, London, 1998. To facilitate usage of the more comprehensive bibliogra- bindman, david, ed., The History of British Art, Volume macleod, catharine and marciari alexander, phy, its materials have been organized under the follow- 2: 1600–1870, London, 2008. julia, eds., Painted Ladies: Women at the Court of ing headings: brewer, john, The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Charles II, exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Culture in the Eighteenth Century, London, 1997. Gallery, London, 2001. general texts: history (social and cultural) craske, matthew, Art in Europe, 1700–1830, Oxford, marciari alexander, julia and macleod, catha- and the history of art 1997. rine, eds., Politics, Transgression, and Representation the london art world: institutions, exhibi- farington, joseph, The Diary of Joseph Farington, at the Court of Charles II, Studies in British Art 18, tions and the art market vols. -

The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine

Études écossaises 16 | 2013 Ré-écrire l’Écosse : histoire A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland Peinture et parenté écossaises : l’influence transparente de l’école écossaise sur les tableaux irlandais d’Erskine Nicol Amélie Dochy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/837 DOI: 10.4000/etudesecossaises.837 ISSN: 1969-6337 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version Date of publication: 15 April 2013 Number of pages: 119-140 ISBN: 978-2-84310-246-2 ISSN: 1240-1439 Electronic reference Amélie Dochy, “A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland”, Études écossaises [Online], 16 | 2013, Online since 15 April 2014, connection on 15 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/837 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.837 © Études écossaises Amélie Dochy Université Toulouse 2 A Scottish Art and Heart: The Transparent Influence of the Scottish School of Art on Erskine Nicol’s Depictions of Ireland “The Arts, unlike the exact sciences, are coloured by the temperaments, beliefs, and outward environment of the peoples amongst whom they flourish.” William D. mCKay, The Scottish School of Painting, 1906, p. 3. Erskine Nicol (3 July 1825–8 March 1904) was a Scottish painter who lived in Dublin between 1845 and 1850. When he went back to Scotland, his paintings attracted the attention of the British public for their fine quality, lively colours and the scenes taken from everyday life, so that by the 1850s, Nicol was already famous and was celebrated by art critics as the painter of Ireland. -

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”.