Phineas Redux Volume II by Anthony Trollope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2020

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.09.2020 - 30.09.2020 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.09.2020 00:03:05 HD 028096 IT DON'T MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE TO MEKEVIN MICHAEL FEAT. WYCLEF ATLANTIC 00:03:43 ANG 01.09.2020 00:06:46 HD 002417 KAMOR ME VODI SRCE NUŠA DERENDA RTVS 00:03:16 SLO 01.09.2020 00:10:09 HD 020765 THE MIDNIGHT SPECIAL CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL ZYX MUSIC 00:04:09 ANG 01.09.2020 00:14:09 HD 029892 ZABAVA TURBO ANGELS RTS 00:02:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:17:06 HD 069164 KILOGRAM NA DAN VICTORY 00:03:20 SLO 01.09.2020 00:20:42 HD 015945 SOMEBODY TO LOVE JEFFERSON AIRPLANE BMG, POLYGRAM,00:02:56 SONY ANG 01.09.2020 00:23:36 HD 054272 UBRANO JAMRANJE ŠALEŠKI ŠTUDENTSKI OKTET 00:05:54 SLO 01.09.2020 00:29:31 HD 004863 RELIGIJA LJUBEZNI REGINA MEGATON 00:03:00 SLO 01.09.2020 00:32:35 HD 017026 F**K IT FLORIDA INC KONTOR 00:03:59 ANG 01.09.2020 00:36:32 HD 028307 BOBMBAY DREAMS ARASH FEAT REBECCA AND ANEELA ORPHEUS MUSIC00:02:51 ANG 01.09.2020 00:39:23 HD 029465 DUM, DUM, DUM POP DESIGN 00:04:02 SLO 01.09.2020 00:43:35 HD 025553 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHRIS ISAAK REPRISE 00:03:17 ANG 01.09.2020 00:46:50 HD 037378 KOM TIMOTEIJ UNIVERSAL 00:02:56 ŠVEDSKI 01.09.2020 00:49:46 HD 017718 VSE (REMIX) ANJA RUPEL DALLAS 00:03:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:53:51 HD 012771 YOU ARE MY NUMBER ONE SMASH MOUTH INTERSCOPE00:02:28 ANG 01.09.2020 00:56:17 HD 021554 39,2 CECA CECA MUSIC00:05:49 SRB 01.09.2020 01:02:04 HD 024103 ME SPLOH NE BRIGA ROGOŠKA SLAVČKA 00:03:13 SLO 01.09.2020 01:05:47 HD 002810 TOGETHER FOREVER RICK ASTLEY -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.09.2020

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.09.2020 - 06.09.2020 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.09.2020 00:03:05 HD 028096 IT DON'T MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE TO MEKEVIN MICHAEL FEAT. WYCLEF ATLANTIC 00:03:43 ANG 01.09.2020 00:06:46 HD 002417 KAMOR ME VODI SRCE NUŠA DERENDA RTVS 00:03:16 SLO 01.09.2020 00:10:09 HD 020765 THE MIDNIGHT SPECIAL CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL ZYX MUSIC 00:04:09 ANG 01.09.2020 00:14:09 HD 029892 ZABAVA TURBO ANGELS RTS 00:02:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:17:06 HD 069164 KILOGRAM NA DAN VICTORY 00:03:20 SLO 01.09.2020 00:20:42 HD 015945 SOMEBODY TO LOVE JEFFERSON AIRPLANE BMG, POLYGRAM,00:02:56 SONY ANG 01.09.2020 00:23:36 HD 054272 UBRANO JAMRANJE ŠALEŠKI ŠTUDENTSKI OKTET 00:05:54 SLO 01.09.2020 00:29:31 HD 004863 RELIGIJA LJUBEZNI REGINA MEGATON 00:03:00 SLO 01.09.2020 00:32:35 HD 017026 F**K IT FLORIDA INC KONTOR 00:03:59 ANG 01.09.2020 00:36:32 HD 028307 BOBMBAY DREAMS ARASH FEAT REBECCA AND ANEELA ORPHEUS MUSIC00:02:51 ANG 01.09.2020 00:39:23 HD 029465 DUM, DUM, DUM POP DESIGN 00:04:02 SLO 01.09.2020 00:43:35 HD 025553 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHRIS ISAAK REPRISE 00:03:17 ANG 01.09.2020 00:46:50 HD 037378 KOM TIMOTEIJ UNIVERSAL 00:02:56 ŠVEDSKI 01.09.2020 00:49:46 HD 017718 VSE (REMIX) ANJA RUPEL DALLAS 00:03:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:53:51 HD 012771 YOU ARE MY NUMBER ONE SMASH MOUTH INTERSCOPE00:02:28 ANG 01.09.2020 00:56:17 HD 021554 39,2 CECA CECA MUSIC00:05:49 SRB 01.09.2020 01:02:04 HD 024103 ME SPLOH NE BRIGA ROGOŠKA SLAVČKA 00:03:13 SLO 01.09.2020 01:05:47 HD 002810 TOGETHER FOREVER RICK ASTLEY -

Mise En Page 1

JOUR DU NOUVEL AN 392 078 nouveaux- Quotidien National d’Information nés à travers Jeudi 02 janvier 2020 N° 2019 Prix: 10 DA - Email: [email protected] - Site: www.journal-lanation.com le monde P24 SIX MORTS DANS UN ACCIDENT DE LA ROUTE À GUERRARA (G HARDAÏA ) Début d’année particulièrement meurtrier sur nos routes P2 CONDAMNÉ À SIX MOIS DE PRISON FERME LUTTE CONTRE LE ÉQUIPE NATIONALE ET UNE ANNÉE AVEC SURSIS GASPILLAGE DU PAIN L’équivalent de L’homme d’affaires Issad 340 millions Rebrab sort de prison P3 dollars à la l PRÉSIDENTE DU TRIBUNAL À P2 PROPOS DE L’AFFAIRE EVCON poubelle 792 millions DA de WILAYA D'A LGER surfacturation Le budget Quatre 2020 Algériens dans dépassera les le onze type 5 200 mds DA P4 des Africains P11 2 JANVIER 2020 LA NATION EVENEMENT 2 SIX MORTS DANS UN ACCIDENT DE LA ROUTE À GUERRARA (G HARDAÏA ) FILIÈRE DE LA POMME DE TERRE Vers la Début d’année particulièrement dynamisation du système meurtrier sur nos routes "SYRPALAC" Le premier jour de l’année 2020 a été particulièrement meurtrier sur nos routes. Un terrible accident de la route a fauché six âmes près de Guerrara dans la wilaya de Ghardaïa. Ainsi, le bilan de seulement 24h est porté à 11 morts et 30 blessés. Le secteur de l'Agriculture, du Développement rural et de la 110 km du chef lieu de wilaya, six (6) Pêche s'emploie, de concert personnes ont trouvé la mort et une avec ses partenaires, à élaborer autre a été blessée dans un accident de une feuille de route pour dyna - la circulation survenu tôt hier, a-t-on appris au - miser le système de régulation A des produits de la large près des services de la Protection civile (PC). -

May/June 2021 • Volume 109 • Number 3 the TENNESSEE BANKER

May/June 2021 • Volume 109 • Number 3 THE TENNESSEE BANKER MEMBER FEATURE Chattanooga's RockPoint Bank Hamp Johnston opens up about the first Chattanooga de novo bank to open since Great Recession PHOTO RECAPS Credit Conference Human Resources Conference The Southeastern School of Consumer Lending I & II AND The success of TBA's Financial Literacy Week VIRTUAL MEETINGS HAVE BEEN GREAT, BUT WE LOOK FORWARD TO SEEING YOU IN PERSON AT TBA’S ANNUAL MEETING IN CHARLESTON, S.C. SOON! 211 Athens Way, Ste 100 Nashville, TN 37228-1383 A wholly owned subsidiary of the Tennessee Bankers Association FinancialPSI.com 1.800.456.5191 VIRTUAL MEETINGS HAVE BEEN GREAT, External Audit | FDICIA Compliance | Internal Audit Outsourcing | SOX 404 Compliance Compliance Testing (A-Z) | Bank Secrecy Act | Loan Review | Fair Lending | Cybersecurity BUT WE LOOK FORWARD TO SEEING YOU IN PERSON Risk Assessments | Tax | Valuation | Due Diligence in Affiliations AT TBA’S ANNUAL MEETING IN CHARLESTON, S.C. SOON! Maybe it’s time to CPA THE PYA WAY We get it. It’s not easy finding a firm that understands banking and is responsive, accessible, transparent, smart, and independent. And it’s not easy building one. For nearly four decades, we have grown our business by investing in people and relationships. PYA has become recognized as one of the most successful firms in the country. Give us a call to learn more about the PYA WAY to earn your trust. 211 Athens Way, Ste 100 800.270.9629 | pyapc.com Nashville, TN 37228-1383 A wholly owned subsidiary of the Tennessee Bankers -

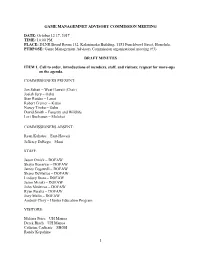

GMAC Meeting Minutes

GAME MANAGEMNET ADVISORY COMMISSION MEETING DATE: October 12 17, 2017 TIME: 10:00 PM PLACE: DLNR Board Room 132, Kalanimoku Building, 1151 Punchbowl Street, Honolulu. PURPOSE: Game Management Advisory Commission organizational meeting (#3) DRAFT MINUTES ITEM 1. Call to order, introductions of members, staff, and visitors; request for move-ups on the agenda. COMMISSIONERS PRESENT: Jon Sabati – West Hawaii (Chair) Josiah Jury – Oahu Stan Ruidas – Lanai Robert Cremer – Kauai Nancy Timko – Oahu David Smith – Forestry and Wildlife Lori Buchanan – Molokai COMMISSIONERS ABSENT: Ryan Kohatsu – East-Hawaii Jefferey DeRego – Maui STAFF: Jason Omick – DOFAW Shaya Honarvar – DOFAW James Cogswell – DOFAW Shane DeMattos – DOFAW Lindsey Ibara – DOFAW Jason Misaki – DOFAW John Medeiros – DOFAW Ryan Peralta – DOFAW Joey Mello – DOFAW Andrew Choy – Hunter Education Program VISITORS: Melissa Price – UH Manoa Derek Risch – UH Manoa Cathrine Cadiente – SHOH Randy Kepuhina 1 ITEM 2. Approval of minutes from June 19, 2017 GMAC meeting. Comm. Buchanan: Do we have a motion from the floor for approval or amendments to the minutes of the June 19 GMAC meeting? Comm. Jury: I move to approve the minutes of the June 19 meeting. Comm. Timko: I’ll second. Comm. Buchanan: Okay, we have a second. Any discussion? No discussion. All those in favor of approval of the minutes of June 19, 2017, raise your right hand. Any abstentions? All raised their hand except commissioner David Smith who abstained. He was not at the June 19th meeting. June 19 2017 minutes are approved. It was requested to move Item 4 before Item 3 and there were no objections. ITEM 4. -

N* Union Harmed

' Second Class Postage paid' Vol. LXXIV. No. 19 3. Pages '.. • CRANFORD; NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MAY.25/1967 'Cranford, New Jersey 07018 TEN CENTS Reveal Parade Plans N* Union ForMemorialBay y Cranl'ord's .-'annual Memorial Day parade will asseinbli^irt 8:30 a.m. Harmed Tuesday, at the. Walnut Avenge School yard. Marchinfc^CyiH" begin at <J o'clock and end at U) "al Memorial Park, iJpringfieW Aye,, monies honoring the township's war dead wilLtfe Cortdqct Marchers will proceed north, on WahjufAvc. to North Ave., swing- west to Eastman St., north -', on -^ Casiman St.. to Central Ave, Asserting, that; thei =rUriion Ave. between tee Tuesday night to lift the cast on Central .to SprineMfil North" and Springfield Aves*. "restfictjorT. '••."'• Ave., turn north on- Sppjfigfield 1 harmed by the/eiiminatiori of 25 merchants along the street Following' -a lengthy hearing, . Ave,, east and then southron. River- parking on tfre"easterly side of petitioned Township Commit- •WMjgtJ^dward K: Gill said the gov- side Dr. /f^ erning" body;-will- endeavor to com- Serving as yfaniY marshal foil plete Us study as quickly as pos- the five-cUyision parade will be sible, taking into consideration the Vincent/-K'. Brtnkerhoff, comman- Suggests Forruation comments of merchants as well as der .^efT New Jersey Department the reports of the police and Traf- yFW. The roll call of the war dead fic Coordinating Committee. The ^vhiph will include the names .of | Of Betail Merchant Group mayor said the plan will be given- " two servicemen' killed in Vietnam | - Formation of a stroogerretail merchants division of the.Chambenof a "fair trial" but, that a determi- —Dean J. -

The Jewish Saint

CHAPTER 5: The Jewish Saint One who would know the secrets of Nature must practice more humanity than others.—Thoreau In late 1933, the most famous living scientist on Earth immigrated to the United States from his native Germany, which had fallen under the dark spell of the Third Reich. Despite worldwide fame, as a Jew, Albert Einstein was persona non grata to the Nazi’s, and his days were numbered. He left in the nick of time. Across the Atlantic, preparations for the prize catch were at fever pitch. The Institute of Advanced Studies had just been created at Princeton University to showcase the originator of the theory of relativity. Dignitaries, festivities, and marching bands awaited his arrival. They were not to be disappointed. As the ship bearing Einstein pulled into dock in New York, the epicenter of physics shifted from Berlin to the United States. Here it has remained for seventy-five years. Grateful but unimpressed, Einstein wrote irreverently of his new home to an old friend: “[Princeton] is a wonderful little spot, a quaint and ceremonious village of puny demigods on stilts. Yet, by ignoring certain social customs, I have been able to create for myself an atmosphere free from distraction and conducive to study.”i There, in an unpretentious home on Mercer Street, he spent the rest of his days (Fig. 10). Figure 1: The house at 112 Mercer Street, Princeton, New Jersey, in which Albert Einstein lived from 1933 until his death in 1955. (Photo credit: the author.) In his adopted country, Einstein was adored by ordinary folk, watched by the FBI, and occasionally revered as a Jewish “saint.” For a rare few, simply meeting Einstein turned mystical. -

01.09.2018 00:03:45 Hd 039551 Give Me Everything (Tonight)

01.09.2018 00:03:45 HD 039551 GIVE ME EVERYTHING (TONIGHT) PITBULL FEAT NE-YO, AFROJACK, NAYER 00:04:02 ANG 01.09.2018 00:07:44 HD 016663 WONDERFUL WORLD SAM COOKE INTERMUSIC00:02:04 ANG 01.09.2018 00:09:39 HD 024391 A PUBLIC AFFAIR (MASH-UP RMX) JESSICA SIMPSON SONY BMG 00:03:31 ANG 01.09.2018 00:13:08 HD 003507 KER VEM BOTRI 00:03:16 SLO 01.09.2018 00:16:41 HD 010345 YOU CAN GET IF YOU REALLY WANT JIMMY CLIFF COLUMBIA 00:02:33 ANG 01.09.2018 00:19:06 HD 018302 MYSTERIOUS TIMES DJ LHASA UNIVERSAL 00:03:25 ANG 01.09.2018 00:22:23 HD 004567 ALI TVOJA MAMA VE SPIN 3P 00:03:11 SLO 01.09.2018 00:25:41 HD 002038 HEAVEN IS A PLACE ON EARTH BELINDA CARLISLE VIRGIN RECORDS00:04:00 ANG 01.09.2018 00:29:33 HD 000031 WHAT'S UP 4 NON BLONDES INTERSCOPE00:04:52 ANG 01.09.2018 00:34:16 HD 006988 JAZ GREM NAPREJ POWER DANCERS MEGATON 00:03:29 SLO 01.09.2018 00:37:52 HD 046345 ECHA PA'LLA (MANOS PA'RRIBA) [ENGLISHPITBULL VERSION] SONY 00:03:14 ANG 01.09.2018 00:41:05 HD 005216 ONLY TIME (REMIX) ENYA REPRISE 00:03:12 ANG 01.09.2018 00:44:10 HD 017821 OBJEMI ME VLADO PILJA 00:04:20 SLO 01.09.2018 00:48:39 HD 010511 MICKEY TONI BASIL 00:03:23 ANG 01.09.2018 00:51:52 HD 040782 DALMATINKA CONNECT FT. -

18Lent for Today

06 Go Calvin! 07 Spirituality 20 A Sacred Circle for Life in the Trenches March 2011 | www.thebanner.org March 18Lent for Today Faith Alive - Dwell (Dean) Faith Alive - Dwell Preview God created all things, and they were good. All things have fallen from that original goodness. Christ, who has redeemed all things, eventually will restore them. We aid the Spirit’s work of restoration by seeking to make all things better. All things encompasses the richness of Calvin’s Reformed theology; it’s also a good way of describing how Calvin equips students for the future. Calvin students explore the academic spectrum—always analyzing, always considering how they can make the world a better place. Calvin people believe God’s words: “See, I am making all things new.” In our minds, that’s a promise—and a call. www.calvin.edu 3201 Burton SE, Grand Rapids, MI 49546 (616) 526-6106 or 1-800-688-0122 Calvin does not discriminate with regard to age, race, color, national origin, sex or disability in any of its educational programs or opportunities, employment or other activities. 12991DM_Banner_AllThings.indd 1 5/25/10 1:31:01 PM Volume 146 | Number 03 | 2011 FEATURES Yes and No: Lent and the Reformed Faith Today 18 Discerning best practices for Lent in our own time and place WEB Q’S by John D. Witvliet A Sacred Circle 20 The sad chapter in Canada’s history of the Indian residential schools leads to a meaningful conversation about reconciliation. by Rebecca Warren with Roy Berkenbosch, Travis Enright, and Maggie Hodgson Talking Biblically about Homosexuality 32 One church’s conversation leads to a request to synod. -

AVIS, 2017/ 2018, Číslo 4

AVIS, 2017/ 2018, číslo 4 Obsah Opýtali sme sa... 3 - 4 Interview (...s nami o vás...) 5 -7 Téma na dnes 8 - 10 - Turistický kurz - Deň životného prostredia Rubrika kynológa 11 Rubrika veterinára 11 Rubrika cestovateľa 12 1 + 1 = ??? 13 Literárne okienko 14 Movie 15 Music 15 - 16 Šikovné ruky 17 Zúčastnili sme sa 17 - 19 2 AVIS, 2017/ 2018, číslo 4 Opýtali sme sa pani učiteľky Ing. Veroniky Gilániovej... 1. O akom povolaní ste snívali v detstve? Kedy sa vo Vás vzbudil záujem stať sa učiteľkou? Ako dieťa som chcela byť herečka, potom novinárka, neskôr právnička, úradníčka. Pomerne často sa to menilo. S myšlienkou učiteľstva som sa začala pohrávať až v poslednom ročníku na vysokej škole. 2. Kde ste študovali a ako si spomínate na Vaše študentské časy? Študovala som na Obchodnej fakulte Ekonomickej univerzity v Bratislave. Strednú školu mám obchodnú akadémiu. Študentské časy mám ešte čerstvo v pamäti, bolo to pekné obdobie, aj keď dosť náročné. 3. Prečo práve cestovný ruch? Keďže pochádzam z turisticky atraktívnej obce Oščadnica a od detstva som prichádzala do styku s cestovným ruchom, bola to akási prirodzená voľba. Myslím si, že práve cestovný ruch a jeho udržateľné formy majú potenciál uživiť túto nádhernú oblasť, akou Žilinský kraj nepochybne je. 4. Prezradili by ste nám Vašu najlepšiu a naopak aj najhoršiu spomienku počas Vášho štúdia? Najlepšie spomienky mám na svoju strednú školu. Boli sme štvorica dobrých kamarátok, doteraz mi chýba svalovica na bruchu od smiechu . A taktiež sme mali výborné vyučujúce, najmä z podnikovej ekonomiky. Naopak, dodnes mám nepríjemné pocity pri spomienke na hodiny matematiky ešte na základnej škole. -

Tasstimesuk-Paper

G-946-38 "All the News that's Tone to Print" IP. Tonetown, Dreamland, Outer Edge --~l):::;ol~. 1~9_-,:.:N:::;o·,.:.7:,8 _____________________________________________________ Wednesday July 78, 1986 GRAHPS VAHISHES Hometown Dogwonder Franklin Snarl Linked to Mysterious Disappearance Wins 6th Consecutive A very strange but lovable Tonetown own somewhere. tor from another parasphere. visitor. who calls himself Gramps, has He was reported last seen around "He was just a great guy," said Ultra Journalism recently disappeared. moonup, June 26, with real estate Stelgad. manager ol the Daglets, as she Gramps was one of the only visitors magnate, Franklin Snarl. ruffled the soft green feathers in her Award who, in spite of his untass apparel, was "It seemed he was resisting some," intense pink hair. well accepted in Tonetown. said one witness who wished to be "He was the one who gave us the Tonetown'sown Ennio, better known After visiting with several of Tone unnamed. great idea for the Zagtone, our ultra as "The Legend,'' has done it again. town's most prominent citizens, like But Snarl denies these reports. "I touch new instrument that's helped He's won the lnter-Moonal Ultra Jour Stelgad of the Daglets, Flo of Flo's Party never heard of the guyl " Snarl insisted. our new tune, 'Tu~,' hit the top," she nal ism Award forthesixthyearina row. Supplies and Nuyu, editor of the Times, Other citizens, however. have given added enthusiastically. This year the canny canine snapped Gramps evidently wandered off on his glowing reports of the strange old visi- Continued on Page 4 up the prize with his investigative arti cle about intra-dimensional travel through a new invention called "The Hoop." At great risk to his health, Ennio Enniogranted us the following inter actually traveled through the hoop and view as he typed upsomeofthestories back again to gain first-hand knowl you see in this issue. -

El Mustang, November 2, 1965

el mustang CALIFORNIA STATE POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE TOLXXVill. No. 10 SAN LUIS OBISPO, CALIFORNIA TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 2 ,1!>65 Student unrest' studied by administrators Waihlnirton (C P S ) — U nlvQ i* * Conn., plncod responsibility for thy prwKenU uml top uulidiniH- student activism on “a half-cen tnton gathered at the- American tury of wenk teaching that in- Council of Education (AUH) con ference recently to discuss the suits atudents by not paying problem! and concern! of their enough uttention to them,” Prof. itudents, but few student* were Gwynn charged that "ineffective there to ipenk or listen. teaching" persists both inside and In almost every session of the outside the classroom, and "one three-day meeting, delegates feels 'that If Socrates is rare In the »ere preaented with the specter dasgtpow, he mtmrbe rarer In the oPitudent unrest” nnd dire pre- ngoru of the coffco-shop or the dictioiii of events even more im- sunetuary of the office.” lettllng than Berkeley unless President of Fisk I'niversity, itudents begin to feel n slake in Stephen J. Wright, Nushville, the university. The conference. Tens,, said that student involve Itself, the tlrst meeting in the' ment in the university was a pre At'E'i 48-year history to focus requisite for a satisfactory aca on “The Student in Higher Ed^i demic atmosphere.. “Without a ration," showed little evidenced student-oriented faculty, the key INTERNATIONAL W IK K . The campua look ent show In campus. The week in which moat of the if itudent participation or plan- to student Involvement,” he said, on hii international flavor during la»l work.