Mariela Ochoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding the Unexpected

By Damien LeRoy | www.damienleroy.com Finding the Unexpected in Honduras Most of us dream of our next kite adventure being to some untouched, far off destination with pristine waters and constant wind where you feel like the only people around for miles are you and your friends. A lot of exotic locations probably come to mind when you try to imagine this dream location, but I’m pretty sure Honduras isn’t one of them. At least not yet. 34 35 Located about 45 miles from the Honduran mainland, the small island of Guanaja might be very similar to that perfect remote location you’ve been dreaming about. Guanaja was Christopher Columbus’s first stop on his last trip to the New World in 1502 and was where he was first exposed to cacao (chocolate). Only three miles wide by seven miles long there are no cars on Guanaja and the only way to travel around the island is by water taxi. The people here have traditionally been fishermen, so Guanaja’s culture is very much linked to the ocean. Most people on Guanaja produce their own food through fishing, raising livestock, or growing personal gardens. Tourism is still in its infancy on Guanaja and if there are 50 tourists on the island at a time it would be considered very busy. Guanaja is part of Honduras, but is really its own little place that feels completely disconnected from the rest of the country and in some ways the rest of the world. Rising out of the beautiful crystal clear Caribbean water to an elevation of 1,500 feet, Guanaja is situated near the end of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, the second largest barrier reef in the world. -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras. -

Images of Black Womanhood in Twentieth-Century Honduran Poesía Negra

L’É RUDIT FRANCO -ESPAGNOL , VOLUME 10, FALL 2016 Love and Perversion: Images of Black Womanhood in Twentieth-Century Honduran Poesía Negra Erin Montero Warren Wilson College Es un aporte, que lleva el sentimiento de un pedazo de nuestro pueblo, que vive arrullado por el mar, trabajando duramente en su parcela humilde, creando el nuevo concepto de la raza, y cultivando sus nobles sentimientos de hondureñidad a través de su piel fina, obscura, adolorida y triste. Claudio Barrera (Prologue 8) Poesía negra is a genre of poetry that developed in various Latin American nations and reached its apogee in the 1930s (Young 137).1 Although it is widely recognized that poesía negra has contributed to the development of Caribbean literature, there are few investigations that acknowledge that Central America witnessed its own encounter with the genre (Morales 19-20). In Honduras, poet and journalist Claudio Barrera (nom de plume for Vicente Alemán) published an anthology of poetry and artwork titled Poesía negra en Honduras (1959); created by various Ladino poets, these poems and images were selected by Barrera to pay homage to the Afro-descendants that have made Honduras their home while creating a space for them within the panorama of Honduran national identity. 2 As Barrera states in the prologue, he wants for his anthology to act as a contribution to support Afro-Hondurans in their creation of a “nuevo concepto de la raza” (8). When considering this space that the Ladino poets and artists of Poesía negra en Honduras have carved out for Afro-Hondurans, we see that the Afro-Honduran woman is touted as an object of love and desire, while her image plays out as a series of tropes such as the 1 In this investigation I use the term poesía negra because that is the term used in the anthology I analyze. -

""A Sad and Bitter Day" Oral Traditions in the Bay Islands of Honduras

""ASad and Bitter Day" Oral Traditions in the Bay Islands of Honduras Surronlading the Wyke Cruz Treaty of I859 Heather R. McLaughlin These words were spoken by a 92 yr. old woman of Caymanian descent living in Roatan, the largest of the Bay Islands of Honduras. She was referring to the day the Wyke Cruz Treaty was signed, ceding the Bay Islands, briefly a British Colony, to the then Spanish Honduras. She and the others interviewed spoke as if the 'day' was a very recent one, when in fact the treaty was signed on Nov. 28, 1859, fully coming into effect in 1861. Despite the fact that little or nothing about the treaty and of the British involvement in the Bay Islands had been taught in the schools, knowledge of it was still very much alive in 1994, when I spent two weeks interviewing there, and was still influencing the lives of a large portion of the inhabitants. This English-speaking group referred to as Caymanos by many Spanish- speaking Hondurans - are primarily the descendants of Caymanian settlers there, and have, through oral tradition, stubbornly held onto their history, both family history and community history, their culture and their language. In the words of one gentleman: "Why I know about my Cayman roots ... I was raised by my grandparents. I lived at home with them. At night-time there was no television. .. not anything in entertainment, so we sat out on the front porch and listened to these ... stories from the old folks."' Migration from the Cayman Islands began in the 1830s; in a letter to the Foreign Office in 1854, the governor of Jamaica commented that it had been reported to him that ".. -

1 Introduction the Media Report Almost Daily About

358 Erdkunde Band 61/2007 DESTRUCTION AND REGENERATION OF TERRESTRIAL, LITTORAL AND MARINE ECOSYSTEMS ON THE ISLAND OF GUANAJA/HONDURAS SEVEN YEARS AFTER HURRICANE MITCH With 7 figures and 4 photos KIM ANDRÉ VANSELOW,MELANIE KOLB and THOMAS FICKERT Keywords: Hurricane Mitch, Islas de la Bahia, Guanaja, disturbance ecology, regeneration Hurrikan Mitch, Islas de la Bahia, Guanaja, Störungsökologie, Regeneration Zusammenfassung: Zerstörungsausmaß und Regeneration terrestrischer, litoraler und mariner Ökosysteme auf der Insel Guanaja/Honduras sieben Jahre nach Hurrikan Mitch Hurrikan Mitch gilt als einer der stärksten atlantischen Wirbelstürme des vergangen Jahrhunderts. Aufgrund seiner für Hurrikane außergewöhnlichen, über drei Tage (27.10 bis 29.10.1998) quasistationären Lage zwischen der Nordküste von Honduras und der vorgelagerten Insel Guanaja wurden diese Bereiche besonders stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen. Die Untersuchung befasst sich mit dem Zerstörungsausmaß, den Auswirkungen (negativen wie positiven) und der lokal recht unterschiedlich verlaufenden Regeneration der drei wichtigsten Ökosysteme der Insel, Kiefernwälder, Mangroven und Korallenriffe, ein gutes halbes Jahrzehnt nach dem Störungsereignis. Da im Zuge der globalen Erwärmung mit einer Zunahme der Hurrikan-Frequenz und Intensität in der Karibik zu rechnen ist, ist das Verständnis der Auswirkungen auf diese sensiblen Ökosysteme von besonderer Bedeutung. Summary: Hurricane Mitch is considered as one of the strongest Atlantic storms of the past century. Due to its extraordinary quasi-stationary position over three days (27.10. by 29.10.1998) offshore between the northern coast of Honduras and the Island of Guanaja, this area was struck most violently. The study deals with the degree of destruction, the impacts (negative ones as well as positive ones) and the locally different trajectories of regeneration seven years after the disturbance event for the three most important ecosystems on Guanaja: pine forests, mangroves and coral reefs. -

Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present

DISASTER HISTORY Signi ficant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900 - Present Prepared for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Developnent Washington, D.C. 20523 Labat-Anderson Incorporated Arlington, Virginia 22201 Under Contract AID/PDC-0000-C-00-8153 INTRODUCTION The OFDA Disaster History provides information on major disasters uhich have occurred around the world since 1900. Informtion is mare complete on events since 1964 - the year the Office of Fore8jn Disaster Assistance was created - and includes details on all disasters to nhich the Office responded with assistance. No records are kept on disasters uhich occurred within the United States and its territories.* All OFDA 'declared' disasters are included - i.e., all those in uhich the Chief of the U.S. Diplmtic Mission in an affected country determined that a disaster exfsted uhich warranted U.S. govermnt response. OFDA is charged with responsibility for coordinating all USG foreign disaster relief. Significant anon-declared' disasters are also included in the History based on the following criteria: o Earthquake and volcano disasters are included if tbe mmber of people killed is at least six, or the total nmber uilled and injured is 25 or more, or at least 1,000 people art affect&, or damage is $1 million or more. o mather disasters except draught (flood, storm, cyclone, typhoon, landslide, heat wave, cold wave, etc.) are included if the drof people killed and injured totals at least 50, or 1,000 or mre are homeless or affected, or damage Is at least S1 mi 1l ion. o Drought disasters are included if the nunber affected is substantial. -

Download Vol. 17, No. 2

5. '6- 2'y-]irt--2 , 1 -< 4-41: 1 * 7 _ i,~ ,i tj ~,'~,4-2 . "in•'4~ ~SJ:f-'f~-47 4 23* :*S;':k f AL 1 4 2.- ~ r-1 4-4- r1 -f- - I I r + , . 4. 45 ' El -4~-- 77 N. -3'4 1(t ~~l.~1+ _.. ~ |.,.iX- 94." JI ~~,I €4, '''ilf,/I,1 '1|---_t;*· 1,·-·4", r».i'[ 1 f„ , -+ · . - 2/4 W L.1 -; N 152 1 17' M# · I ' ft "39 of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 17 1973 Number 2 THE HERPETOFAUNA oF THE ISLAS DE LA BAHIA, HONDURAS Larry David Wilson Donald E. Hahn - 0 9.: . t.*, ..J , ''. '/'~:,1!''l, "',i , .1: '„,t?'' -'.5 , "4': 't. UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. OLIVER L. AUSTIN, JR., Editor Consultants for this issue: HOWARD W. CAMPBELL Roy McDIARMID Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publication and all manu- scripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Museum R6ad, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32601. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $2308.05 or $2.30.8 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of our researches in the natural sciences, emphasizing the Circum-Caribbean Re- gion. Publication date: 21 May, 1973 Price: $2.35 THE HERPETOFAUNA OF THE ISLAS DE LA BAHIA, HONDURAS LARRY DAVID WILSON AND DONALD E. -

Mangrove Peat Collapse Following Mass Tree Mortality: Implications for Forest Recovery from Hurricane Mitch Donald R

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR Environmental Sciences Faculty and Staff Environmental Sciences Publications 12-2003 Mangrove Peat Collapse Following Mass Tree Mortality: Implications for Forest Recovery from Hurricane Mitch Donald R. Cahoon National Wetlands Research Center (U.S.) Philippe Hensel National Wetlands Research Center (U.S.) John M. Rybczyk Western Washington University, [email protected] Karen L. McKee Edward Proffitt See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/esci_facpubs Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cahoon, D. R., Hensel, P., Rybczyk, J., McKee, K. L., Proffitt, C. E. and Perez, B. C. (2003), Mass tree mortality leads to mangrove peat collapse at Bay Islands, Honduras after Hurricane Mitch. Journal of Ecology, 91: 1093–1105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00841.x This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Sciences at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Sciences Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Donald R. Cahoon, Philippe Hensel, John M. Rybczyk, Karen L. McKee, Edward Proffitt, and Brian C. Perez This article is available at Western CEDAR: https://cedar.wwu.edu/esci_facpubs/39 Journal of Blackwell Science, Ltd Ecology 2003 Mass tree mortality leads to mangrove peat collapse at Bay 91, 1093–1105 Islands, Honduras after Hurricane Mitch DONALD R. CAHOON, PHILIPPE HENSEL*, JOHN RYBCZYK†, KAREN L. MKEE, C. EDWARD PROFFITT and BRIAN C. PEREZ* US Geological Survey, National Wetlands Research Center, Lafayette, LA 70506, USA, *Johnson Controls, Inc. -

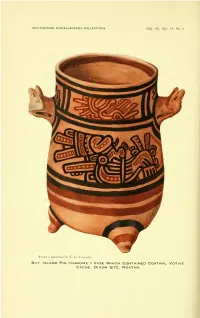

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 92, NO. 14, PL. 1 From a ]iaiiitiii,i; hy K. G. C BAY Island Polychrome I Vase Which Contained Central Votive Cache, Dixon site. Roatan SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 92, NUMBER 14 (End of Volume) ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE BAY ISLANDS, SPANISH HONDURAS (With 33 Plates) BY WILLIAM DUNCAN STRONG Anthropologist, Bureau of American Ethnology [Publication 32901 CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION FEBRUARY 12, 1935 BALTIMORE, UD., U. 8. A. 1 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction i Environmental background 3 Historical and ethnological background 7 Explorations 20 Utila Island 20 Black Rock Basin 20 Site I, urn and skull burials 20 Site 2 28 Brandon Hill Cave 30 Byron Cave 32 Big Bight Cave 33 " Eighty Acre " and other sites 34 Roatan Island 36 Port Royal 36 Jonesville Bight 42 Site I 43 Ceramics 44 Other artifacts 48 Site 2 50 French Harbor 5° The Dixon site 5 Ceramics 53 Metal 60 Ground stone 62 Chipped stone 69 Shell 71 Vicinity of Coxen Hole 7^ Helena Island 74 Caves I and 2 75 Ceramics 76 Ground stone 82 Chipped stone 82 Shell and wood 82 Barburata Island 84 Indian Hill 86 Site I 86 Ceramics 87 Metal 106 Ground stone 107 Chipped stone no Shell 1 10 Bone Ill Human, animal, and other remains in iii IV CONTENTS VOL. 92 PAGE Site 2 Ill Ceramics 113 Comparison of sites i and 2 115 Other sites 117 Morat Island 118 Bonacca Island 119 Stanley Hill 120 Kelly Hill 121 Pine Ridge 122 The Sacrificial Spring 123 Marble Hill Fort 125 The Plan Grande site 129 Michael Rock 135 The Mitchell-Hedges collection in the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation 136 Summary and comparison 140 The Bay Islands 140 Table i, summary of Bay Island sites 142 Table 2, association of Bay Island ceramic types 145 Northern Honduras east of Ceiba 147 The Uloa River region 148 Copan and other Maya Sites 151 The interior of Honduras 159 Western Nicaragua and northern Costa Rica 162 Eastern Nicaragua 166 Conclusion 167 Literature cited 172 . -

Utila, Honduras) Frances Heyward Currin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Transformation of paradise: geographical perspectives on tourism development on a small Carribbean island (Utila, Honduras) Frances Heyward Currin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Currin, Frances Heyward, "Transformation of paradise: geographical perspectives on tourism development on a small Carribbean island (Utila, Honduras)" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 3520. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3520 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSFORMATION OF PARADISE: GEOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVES ON TOURISM DEVELOPMENT ON A SMALL CARIBBEAN ISLAND (UTILA, HONDURAS) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Frances Heyward Currin B.A., University of Memphis, 1999 December, 2002 Acknowledgements There were so many people involved in this creation process and I will be forever indebted, thank you. First I would like to thank Dr. “Skeeter” Dixon, without whom I would never have found this place or this project. Secondly I would like to thank the members of my committee, for keeping your door open and “the light on”, especially Dr. -

Vulnerability Analysis to Climate Change in the Caribbean Belize, Guatemala and Honduras

VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS TO CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CARIBBEAN BELIZE, GUATEMALA AND HONDURAS Photo: Calina Zepeda. Photos front page: F.Secaira and C.Zepeda (TNC) Prime Contract No.EPP – 1-05 -04 – 00020 – 00 TNC Reviewed by: Juan Carlos Villagrán & Zulma de Mendoza (Regional Staff members). This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC). Prepared by: Climate Change and Watersheds Program, Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center. Lenin Corrales Pablo Imbach Claudia Bouroncle Juan Carlos Zamora Daniel Ballestero Mesoamerican Reef Program, The Nature Conservancy Fernando Secaira Hernando Cabral Ignacio March James Rieger 2 FOREWORD: THE USAID REGIONAL PROGRAM FOR AQUATIC RESOURCES MANAGEMENT AND ECONOMIC ALTERNATIVES AND ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE The objective of the USAID Region Program for Water Resources Management and Economic Alterna- tives is to reinforce the management of resources on the Central American coast, reduce threats relating to unsustainable fishing and coastal development practices, support biodiversity conservation and im- prove lifestyles of towns in the region. Climate change will have a serious effect on coral reefs, sea beds, beaches and coastal wetlands, all ecosystems that sustain fisheries and tourism, the main means of living for the population; and it will likewise severely affect the infrastructure of the countries’ communities, cities and the businesses. The implementation of methods for adapting to climate change is therefore a key element of the Regional Program, in order to maintain functionality of the ecosystems that sustain fishing and tourism and to improve the communities’ adaptive capacity. -

New and Noteworthy Bird Records from Guatemala and Honduras

S. N. G. Howell & S. Webb 42 Bull. B.O.C. 1992 112(1) New and noteworthy bird records from Guatemala and Honduras by Steve N . G. Howell & Sophie Webb Received 30 April 1991 As with many areas of Central America, much remains to be learned about the occurrence and distribution of birds in Guatemala and Honduras. These countries have been visited infrequently by ornithologists in the past 25 years and consequently little recent data exists about their avifauna. This paper is based on a total of eight weeks of field work in Guatemala during May and June 1988 (Howell & Webb) and February and March 1991 (Howell), and four weeks in Honduras in June 1988 (Howell & Webb) and March 1991 (Howell). The following list represents signifi cant information concerning 40 species and one hybrid, including three species new to the Guatemalan avifauna and two new to Honduras. We also update status information for certain species, the most recent information for many of which is otherwise that given by Monroe (1968) for Honduras, and Land (1970) for Guatemala. FULVOUS WHISTLING-DUCK Dendrocygna bicolor Honduras: at Lake Yojoa, Dpto. Cortés, 12–15 birds on 28 May, and 70 birds on 30 May 1988. While the species is known to breed at Lake Yojoa, the highest number recorded there in the past was 30 birds (Monroe 1968). MASKED DUCK Oxyura dominicensis Honduras: this shy and little-known duck has been reported rarely from Honduras (Monroe 1968) and is not known to breed in the country. S . N. G. Howell & S. Webb 43 Bull.