RP Blackmur and Randall Jarrell on Literary Magazines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

She Whose Eyes Are Open Forever”: Does Protest Poetry Matter?

commentary by JAMES GLEASON BISHOP “she whose eyes are open forever”: Does Protest Poetry Matter? ne warm June morning in 1985, I maneuvered my rusty yellow Escort over shin-deep ruts in my trailer park to pick up Adam, a young enlisted aircraft mechanic. Adam had one toddler and one newborn to Osupport. My two children were one and two years old. To save money, we carpooled 11 miles to Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York. We were on a flight path for B-52s hangared at Griffiss, though none were flying that morning. On the long entryway to the security gate, Adam and I passed a group of people protesting nuclear weapons on base. They had drawn chalk figures of humans in our lane along the base access road. Adam and I ran over the drawings without comment. A man. A pregnant woman. Two children—clearly a girl and boy. As I drove toward the security gate, a protestor with long sandy hair waved a sign at us. She was standing in the center of the road, between lanes. Another 15 protestors lined both sides of the roads, but she was alone in the middle, waving her tall, heavy cardboard sign with block hand lettering: WE DON’T WANT YOUR NUKES! A year earlier, I’d graduated from college and joined the Air Force. With my professors’ Sixties zeitgeist lingering in my mind, I smiled and waved, gave her the thumbs up. Adam looked away, mumbled, “Don’t do that.” After the gate guard checked our IDs, Adam told me why he disliked the protestors. -

Randall Jarrell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Randall Jarrell - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Randall Jarrell(May 6, 1914 – October 14, 1965) Poet, critic and teacher, Randall Jarrell was born in Nashville, Tennessee, to Anna (Campbell) and Owen Jarrell on May 6, 1914. Mr. Jarrell attended the Vanderbilt University and later taught at the University of Texas. Mr. Jarrell also taught a year at Princeton and also at the University of Illinois; he did a two-year appointment as Poetry Consultant at the Library of Congress. Randall Jarrell published many novels througout his lifetime and one of his most well known works was in 1960, "The Woman at the Washington Zoo". Upon Mr. Jarrells passing, Peter Taylor (A well known fiction writer and friend of Mr. Jarrell) said, "To Randall's friends there was always the feeling that he was their teacher. To Randall's students there was always the feeling that he was their friend. And with good reason for both." Lowell said of Jarrell, "Now that he is gone, I see clearly that the spark of heaven really struck and irradiated the lines and being of my dear old friend—his noble, difficult and beautiful soul." www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 90 North At home, in my flannel gown, like a bear to its floe, I clambered to bed; up the globe's impossible sides I sailed all night—till at last, with my black beard, My furs and my dogs, I stood at the northern pole. There in the childish night my companions lay frozen, The stiff fur knocked at my starveling throat, And I gave my great sigh: the flakes came huddling, Were they really my end? In the darkness I turned to my rest. -

Elizabeth Bishop's "Damned 'Fish'"

Journal X Volume 3 Number 2 Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 1999) Article 5 2020 The One That Got Away: Elizabeth Bishop's "damned 'Fish'" Anne Colwell University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Colwell, Anne (2020) "The One That Got Away: Elizabeth Bishop's "damned 'Fish'"," Journal X: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jx/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal X by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colwell: The One That Got Away: Elizabeth Bishop's "damned 'Fish'" The One That Got Away: Elizabeth Bishop's “damned Fish’” Anne Colwell Anne Colwell, an Everyone who writes about Elizabeth Bishops Associate Professor of poems must comment on her "powers of observa English at the Univer tion.” It’s a rule. Randall Jarrell’s famous early sity ofDelawar e, is the review remains one of the pithiest of these com ments: "All her poems have written underneath I author of Inscrutable have seen it” (235). And many critics, before and Houses: Metaphors since Jarrell, base their readings of Bishop’s poems on of the Body in the the assumption of her realism. Lloyd Frankenberg Poems of Elizabeth writes, "hers is a clearly delineated world” of "percep- Bishop (U ofAlabama tion[,] precision, compression” (331, 333). Walker P). Her poems appear Percy argues that the true subject of her poetry is the act of perception itself (14). -

Poetry for the People

06-0001 ETF_33_43 12/14/05 4:07 PM Page 33 U.S. Poet Laureates P OETRY 1937–1941 JOSEPH AUSLANDER FOR THE (1897–1965) 1943–1944 ALLEN TATE (1899–1979) P EOPLE 1944–1945 ROBERT PENN WARREN (1905–1989) 1945–1946 LOUISE BOGAN (1897–1970) 1946–1947 KARL SHAPIRO BY (1913–2000) K ITTY J OHNSON 1947–1948 ROBERT LOWELL (1917–1977) HE WRITING AND READING OF POETRY 1948–1949 “ LEONIE ADAMS is the sharing of wonderful discoveries,” according to Ted Kooser, U.S. (1899–1988) TPoet Laureate and winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. 1949–1950 Poetry can open our eyes to new ways of looking at experiences, emo- ELIZABETH BISHOP tions, people, everyday objects, and more. It takes us on voyages with poetic (1911–1979) devices such as imagery, metaphor, rhythm, and rhyme. The poet shares ideas 1950–1952 CONRAD AIKEN with readers and listeners; readers and listeners share ideas with each other. And (1889–1973) anyone can be part of this exchange. Although poetry is, perhaps wrongly, often 1952 seen as an exclusive domain of a cultured minority, many writers and readers of WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS (1883–1963) poetry oppose this stereotype. There will likely always be debates about how 1956–1958 transparent, how easy to understand, poetry should be, and much poetry, by its RANDALL JARRELL very nature, will always be esoteric. But that’s no reason to keep it out of reach. (1914–1965) Today’s most honored poets embrace the idea that poetry should be accessible 1958–1959 ROBERT FROST to everyone. -

PDF Download William Carlos Williams: Selected Poems

WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS: SELECTED POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Carlos Williams,Robert Pinsky | 200 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | The Library of America | 9781931082716 | English | New York, United States William Carlos Williams: Selected Poems PDF Book Eliot, and John Berryman. In addition to including many more pieces, Tomlinson has organized the whole in chronological order. Nobody'll ever see the kid's name in print, anyway. He's humorous, energetic, and kind-hearted: "Flowers By the Sea" When over the flowery, sharp pasture's edge, unseen, the salt ocean lifts its form--chicory and daisies tied, released, seem hardly flowers alone but color and the movement--or the shape perhaps--of restlessness, whereas the sea is circled and sways peacefully upon its plantlike stem Here, to me, flowers represent individuals - lovely, fragile and cranky, who could be overtaken by life's greater considerations the ocean , but by some grace are left to live and grow. I will surely seek out more of his work when I get a chance. View 2 comments. That's exactly how slow going it was. I felt flames coming out of the poems some of them gentle which warmed up my day, and others very strong, which deeply penetrated inside some of my very painful wounds cauterizing them. From the Introduction by Randall Jarrell: "When you have read Paterson you know for the rest of your life what it is like to be a waterfall; and what other poet has turned so many of his readers into trees? Selected Poems by William Carlos Williams ,. Dec 13, Anima rated it it was amazing. -

Randall Jarrell ' S Poetry of Aerial Warfare

Randall Jarrell 's Poetry of Aerial Warfare ALEX A. VARDAMIS A GENERATION OF AMERICAN poets, such as Robert Lowell, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhard, John Ciardi, Richard Wilbur and W. D. Snodgrass, was engulfed by the tragic enormities of World War 11. Their sensitive and often insightful poems convey the personal and political upheavals caused by that war. None of these poets, however, can match the unerring skill and powers of observation of Randall Jarrell (1914-1965) in communicating the sensations, thoughts and emotions- the entire experience-f the airman from basic training through aerial combat and the eventual return to peacetime. If the U. S. Air Force were to select its poet laureate, Jarrell should be a leading contender. Jarrell, who enlisted in the U. S. Army Air Corps shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, served from 1942 to 1946 at bases such as Sheppard Field, Exas; Chanute Field, Illinois; and Davis-Monthan Field in Arizona. Unable to qualify for pilot status, Jarrell, holding an A.B. and M.A. from Vanderbilt University, was assigned to teach navigation. Appropriately for a poet, one of his specialties was celestial navigation. Although he did not personally Quotation from Jartell's poems and his commentary on these poems are taken from The Complete Poems, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969. War, Literature, and the Arts experience combat, Jarrell listened carefully to the flight crews returning from action and absorbed their stories of bravery, suffering, fear, and death. His knowledge of aviation, his powerful imagination and his creative powers enabled him to visualize and vividly express the human dimensions of aerial warfare, and his sense of brotherhood with his colleagues in arms invested his poetry with human compassion and understanding. -

Graduate Poetry Workshop: Narrative Poetry, Dramatic Monologue, and Verse-Drama Spring 2016

San José State University Department of English and Comparative Literature ENGLISH 240: Graduate Poetry Workshop: Narrative Poetry, Dramatic Monologue, and Verse-Drama Spring 2016 Instructor: Prof. Alan Soldofsky Office Location: FO 106 Office hours: M T W 2:30 – 4:00 pm; and Th, pm by appointment Telephone: 408-924-4432 Email: [email protected] Class Days/Time: M 7:00 – 9:45 PM Classroom: Clark 111 (Incubator Classroom) Course Description Why be yourself when you can be somebody interesting. – Philip Levine It is impossible to say what I mean! – T. S. Eliot Dramatic monologue is in disequilibrium with what the speaker reveals and understands. – Robert Langbaum In this MFA-level poetry workshop, we will explore varieties of narrative poetry and dramatic monologues. We will write and read poems that are based on narrative and dramatic conventions, often written in the voices of a persona or even multiple personas. To stimulate your writing new poems in this course, we will sample narrative poems that we can read as models for our work from the Victorian era (Browning and Tennyson) to the modern (T.S. Eliot, Robinson Jeffers, Edward Arlington Robinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Randall Jarrell, Robert Lowell, John Berryman) to the postmodern (Ai, John Ashbery, Carol Ann Duffy, Terrance Hayes, Juan Felipe Herrera, Denis Johnson, James Tate, and others). Course Goals and Student Learning Objectives Course Goals: • Complete a portfolio consisting of (depending on length) of six to eight finished (revised) original poems, at least three of which should be spoken by a persona, one of which is at least three pages long (could be in the form of a verse drama). -

Who Killed Poetry?

Commentary Who Killed Poetry? Joseph Epstein There are certain things in which mediocrity the best of their work was already behind them. is intolerable: poetry, music, painting, public The audience for poetry was then less than vast; eloquence. it had diminished greatly since the age of -LA BRUYRE Browning and Tennyson. In part this was owing to the increased difficulty of poetry, of which AM NOT about to say of poetry, as T. S. Eliot, in 1921, had remarked: "It appears Marianne Moore once did, that "I, too, likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists, dislike it," for not only has reading poetry brought at present, must be difficult." Eliot's justification me instruction and delight but I was taught to for this difficulty-and it has never seemed quite exalt it. Or, more precisely, I was taught that persuasive-is that poetry must be as complex as poetry was itself an exalted thing. No literary the civilization it describes, with the modem poet genre was closer to the divine than poetry; in no becoming "more comprehensive, more allusive, other craft could a writer soar as he could in a more indirect." All this served to make the modern poem. When a novelist or a dramatist wrote with poet more exclusive as well, which, for those of the flame of the highest inspiration, his work was us who adored (a word chosen with care) modern said to be "touched by poetry"-as in the phrase poetry, was quite all right. Modern poetry, with "touched by God." "The right reader of a good the advance of modernism, had become an art for poem," said Robert Frost, "can tell the moment the happy few, and the happy few, it must be said, it strikes him that he has taken an immortal are rarely happier than when they are even fewer. -

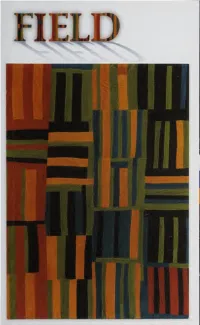

FIELD, Issue 81, Fall 2009

FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 81 FALL 2009 OBERLIN COLLEGE PRESS EDITORS David Young David Walker ASSOCIATE Pamela Alexander EDITORS EDITOR-AT- Martha Collins LARGE MANAGING Linda Slocum EDITOR EDITORIAL Dain Chat el ASSISTANTS Yitka Winn DESIGN Steve Farkas www.oberlin.edu/ocpress Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Subscriptions and manuscripts should be sent to FIELD, Oberli, College Press, 50 North Professor Street, Oberlin, OH 44074 Man ™ * * «■£ ^' “«»>»» years / $40.00 to, ear for r , § ‘SSUeS $8'°° P°StPaid- Pl^ add $4-00 pe, Back issues tom , !f and $9.00 for all other countries issues $12.00 each. Contact us about availability. FIELD is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Copyright © 2009 by Oberlin College. ISSN: 0015-0657 CONTENTS 5 Philip Levine: A Symposium Peter Klappert 10 "To a Child Trapped in a Barber Shop": And We Stopped Crying Lee Upton 15 "Animals Are Passing from Our Lives": Yes. Yes, This Pig Edward Hirsch 19 "They Feed They Lion": Lionizing Fury Kathy Fagan 24 "Let Me Begin Again": Nice Work If You Can Get It Kate Daniels 29 "The Fox": A Vision Tom Sleigh 36 "The Two": Wringing the Neck of Eloquence David St. John 42 "Call It Music": Breath's Urgent Song * * * Philip Levine 48 A Wall in Naples and Nothing More 49 Scissors Betsy Sholl 50 Genealogy 51 Goldfinch Jesse Lee Kercheval 52 Blackbird Lee Upton 54 The Mermaids Sang to Me 55 Modesty Debra Allbery 57 Fault 58 Piazza di Spagna, 1821 Alice George 59 Avalon Alison Palmer 60 Vertigo 61 Days Fallen Into Sherod Santos 62 The Memory-Keeper Elizabeth Breese 63 Grenora, N. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA American Poetry at Mid

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA American Poetry at Mid-Century: Warren, Jarrell, and Lowell A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Joan Romano Shifflett Washington, D.C. 2013 American Poetry at Mid-Century: Warren, Jarrell, and Lowell Joan Romano Shifflett, Ph.D. Director: Ernest Suarez, Ph.D. This dissertation explores the artistic and personal connections between three writers who helped change American poetry: Robert Penn Warren, Randall Jarrell, and Robert Lowell. All three poets maintained a close working relationship throughout their careers, particularly as they experimented with looser poetic forms and more personal poetry in the fifties and after. Various studies have explored their careers within sundry contexts, but no sustained examination of their relationships with one another exists. In focusing on literary history and aesthetics, this study develops an historical narrative that includes close-readings of primary texts within a variety of contexts. Established views of formalism, high modernism, and the New Criticism are interwoven into the study as tools for examining poetic structure within selected poems. Contexts concerning current criticism on these authors are also interlaced throughout the study and discussed in relation to particular historical and aesthetic issues. Having closely scrutinized the personal exchanges and creative output of all three poets, this study illuminates the significance of these writers’ relationships to American poetry at mid- century and beyond. Though the more experimental schools of poetry would not reach their height until the 1950s, by the 1940s Warren, Jarrell, and Lowell were already searching for a new aesthetic. -

"I Take My Stance with Care in Such a World" Pacifism, Quakerism, And

"I TAKE MY STANCE WITH CARE IN SUCH A WORLD": PACIFISM, QUAKERISM, AND HISTORY IN THE WORKS OF WILLIAM STAFFORD By DONALD BALL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1996 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this dissertation to my son Matthew and my daughter Caitlin, hoping that they might also one day believe in and work for peace. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank my chair, Dr. Brandon Kershner, for his empathy and sure guidance through a difficult project. Words cannot convey my debt. Dr. Donald Justice, Dr. Alistair Duckworth, Dr. Andrew Gordon, and Dr. Samuel Hill also claim my deepest gratitude for their help and understanding in completing this dissertation. I wish to thank as well my great friend Bob Bateman, my Men's Center group, and especially my mother and family for their persistent help and belief. Finally, my heartfelt gratitude goes out to William Stafford himself who, before his death, offered generous responses to my numerous questions. May he rest in the peace he so believed in. PREFACE Learning about the poetry of William Stafford, his pacifism, and his spiritual beliefs has been a profound experience. My own personal biases and involvement in this project are complex. In 1971 at 19, I found myself sailing across the Atlantic standing precariously on the deck of the USS Shreveport. A Naval Academy midshipman at the time, I remember a moment of revelation on that deck in which I wondered what must have been obvious to others: why would people devote so much time, energy, and money to building a ship whose sole purpose was to kill other people? Yet my father had been a naval officer in World War II, and from my own voracious (bloodthirsty) reading of military history, defending my country seemed a noble, morally sanctioned pursuit. -

When Elizabeth Bishop Published Her First Book North & South

ELIZABETH BISHOP: POET OR CHARACTER? THE RECEPTION OF BISHOP'S WORK IN THE UNITED STATES AND IN BRAZIL Regina M. Przybycien* hen Elizabeth Bishop published her first book North & South and for many years afterwards, her talent was aknowledged and Wpraised mostly by other poets. John Ashbery said of her that she was "the writer's, writer's writer". While some of her friends rapidly became public figures who moved at ease in literary and bohemian circles in New York, she travelled most of the time, shunning the visibility, the public exposure that seemed to accompany a literary career. Thus, for a long time, she was largely ignored by the scholars and the general reading public. Of an older generation of poets, Marianne Moore was her first mentor and remained her lifelong friend. One can trace Moore's influence in Bishop's early poems, in her formal rigor, in the precision of her images, and in her fastidiousness. Among her contemporaries, Robert Lowell, whom she met in New York right after the publication of her first book, became a close friend, an interlocutor for poetic discussions, and a promoter of her work (it was usually Lowell who learned of poetry awards, sent her the application forms, and * Universidade Federal do Paraná 107 Letras, Curitiba, n. 49, p. 107-124. 1998. Editora da UFPR PRZYB YCIEN, R. M. Elizabeth Bishop: poet or character? recommended her work for grants). Randall Jarrell, who besides being a poet, was one of the most influential poetry critics of his time, wrote sweeping reviews of her work.