Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com Now Available in Paperback Recent & Classic Titles

2017 The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Now available in paperback Recent & Classic Titles & Pax Romana Augustus War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World First Emperor of Rome ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY Renowned scholar Adrian Goldsworthy Caesar Augustus’ story, one of the most turns to the Pax Romana, a rare period riveting in western history, is filled with when the Roman Empire was at peace. A drama and contradiction, risky gambles vivid exploration of nearly two centuries and unexpected success. This biography of Roman history, Pax Romana recounts captures the real man behind the crafted real stories of aggressive conquerors, image, his era, and his influence over two failed rebellions, and unlikely alliances. millennia. “An excellent book. First-rate.” Paper 2015 640 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps —Richard A. Gabriel, Military History 978-0-300-21666-0 $20.00 Paper 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. Cloth 2014 624 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps 978-0-300-23062-8 $22.00 978-0-300-17872-2 $35.00 Hardcover 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. 978-0-300-17882-1 $32.50 Caesar Life of a Colossus Recent & Classic Titles ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY This major new biography by a distin- guished British historian offers a remark- In the Name of Rome ably comprehensive portrait of a leader The Men Who Won the Roman Empire whose actions changed the course of ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY; WITH A NEW PREFACE Western history and resonate some two A world-renowned authority offers a thousand years later. -

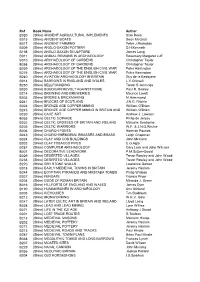

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected]

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 61 Article 3 Number 61 Fall 2009 10-1-2009 The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Duchesne, Ricardo (2009) "The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 61 : No. 61 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol61/iss61/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Duchesne: The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordi The Aristocratic Warlike Ethos of Indo-Europeans and the Primordial Origins of Western Civilization—Part Two1 Ricardo Duchesne [email protected] Western civilization has been the single most war-ridden, war- dominated, and militaristic civilization in all human history. Robert Nisbet [Mycenaean] society was not the society of a sacred city, but that of a military aristocracy. It is the heroic society of the Homeric epic, and in Homer's world there is no room for citizen or priest or merchant, but only for the knight and his retainers, for the nobles and the Zeus born kings, 'the sackers of cities.' Christopher Dawson [T]he Greek knows the artist only in personal struggle... What, for example, is of particular importance in Plato's dialogues is mostly the result of a contest with the art of orators, the Sophists, the dramatists of his time, invented for the purpose of his finally being able to say: 'Look: I, too, can do what my great rivals can do; yes, I can do it better than them. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Susan A. Johnston

CURRICULUM VITAE Susan A. Johnston January 2020 Address: 14111 Westholme Ct. Bowie, MD 20715 (301) 809-4283 Present Position: Associate Professorial Lecturer, Associate Research Professor Anthropology Department, The George Washington University Education: August 1989 PhD in Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania "Prehistoric Irish Petroglyphs: Their Analysis and Interpretation in Anthropological Context" May 1984 Master of Arts in Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania "Sample Selection and Radiocarbon Dating in Early Bronze Age Europe" 1978 - 1979 Durham University, Durham, England Junior year abroad, courses in English and Egyptology 1976 - 1980 Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA Bachelor of Arts degree in English Field Experience: 2016-current Director, Archaeological field school at Dún Ailinne, Co. Kildare, Ireland, in collaboration with New York University and the Blackfriary Archaeology Field School 2006-2008 Geophysical survey at Dún Ailinne, Co. Kildare, including gradiometry, resistivity, and topography 1993- 1996 Program in Public Archaeology, University of Rhode Island Project Archaeologist 1986 PhD fieldwork in Ireland for dissertation, a study of prehistoric Irish petroglyphs consisting of library research, examinations of the sites, and recording of details of motif, environment, and topography 1985, 1986 Printzhof site, Essington, PA, director Dr. Marshall Becker. Supervised excavation of Native American and historical features 1984 Knowth, Ireland, director Prof. George Eogan. Supervised drawing of sections for publication 1983 Danebury, England, director Prof. Barry Cunliffe. Excavator 2 1983 Knowth, Ireland, director Prof. George Eogan. Drew sections of Neolithic megalithic tomb 1981 Danebury, England, director Prof. Barry Cunliffe. Excavator 1981 Spong Hill, England, director Dr. Catherine Hills. Excavated and recorded Anglo-Saxon and Roman features Publications: In press New radiocarbon dates for Dún Ailinne, Co. -

Celts Ancient and Modern: Recent Controversies in Celtic Studies

Celts Ancient and Modern: Recent Controversies in Celtic Studies John R. Collis As often happens in conferences on Celtic Studies, I was the only contributor at Helsinki who was talking about archaeology and the Ancient Celts. This has been a controversial subject since the 1980s when archaeologists started to apply to the question of the Celts the changes of paradigm, which had impacted on archaeology since the 1960s and 1970s. This caused fundamental changes in the way in which we treat archaeological evidence, both the theoretical basis of what we are doing and the methodologies we use, and even affecting the sorts of sites we dig and what of the finds we consider important. Initially it was a conflict among archaeologists, but it has also spilt over into other aspects of Celtic Studies in what has been termed ‘Celtoscepticism’. In 2015–2016 the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland put on exhibitions (Farley and Hunter 2015) based largely on these new approaches, raising again the conflicts from the 1990s between traditional Celticists, and those who are advocates of the new approaches (‘New Celticists’), but it also revived, especially in the popular press, misinformation about what the conflicts are all about. Celtoscepticism comes from a Welsh term celtisceptig invented by the poet and novelist Robin Llywelin, and translated into English and applied to Celtic Studies by Patrick Sims-Williams (1998); it is used for people who do not consider that the ancient people of Britain should be called Celts as they had never been so-called in the Ancient World. -

History, Philosophy, Religion, Science, and the Humanities

Citizenship: A Very Short Introduction VERY SHORT INTRODUCTIONS are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide. The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology. Very Short Introductions available now: AFRICAN HISTORY CHAOS Leonard Smith John Parker and Richard Rathbone CHOICE THEORY Michael Allingham AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTIES CHRISTIAN ART Beth Williamson AND ELECTIONS L. Sandy Maisel CHRISTIANITY Linda Woodhead THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY CITIZENSHIP Richard Bellamy Charles O. Jones CLASSICS Mary Beard and ANARCHISM Colin Ward John Henderson ANCIENT EGYPT Ian Shaw CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Julia Annas Helen Morales ANCIENT WARFARE CLAUSEWITZ Michael Howard Harry Sidebottom THE COLD WAR Robert McMahon ANGLICANISM Mark Chapman CONSCIOUSNESS Susan Blackmore THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE John Blair CONTEMPORARY ART ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia Julian Stallabrass Antisemitism Steven Beller CONTINENTAL PHILOSOPHY ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn Simon Critchley ARCHITECTURE Andrew Ballantyne COSMOLOGY Peter Coles ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes THE CRUSADES Christopher Tyerman ART HISTORY Dana Arnold CRYPTOGRAPHY ART THEORY Cynthia Freeland Fred Piper and Sean Murphy THE HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY DADA AND SURREALISM Michael Hoskin David Hopkins ATHEISM Julian Baggini DARWIN Jonathan Howard AUGUSTINE Henry Chadwick THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS AUTISM Uta Frith Timothy Lim BARTHES Jonathan Culler DEMOCRACY Bernard Crick BESTSELLERS John Sutherland DESCARTES Tom Sorell THE BIBLE John Riches DESIGN John Heskett THE BRAIN Michael O’Shea DINOSAURS David Norman BRITISH POLITICS Anthony Wright DOCUMENTARY FILM BUDDHA Michael Carrithers Patricia Aufderheide BUDDHISM Damien Keown DREAMING J. -

Ethics, a Very Short Introduction

Ethics: A Very Short Introduction ‘This little book is an admirable introduction to its alarming subject: sane, thoughtful, sensitive and lively’ Mary Midgley, Times Higher Education Supplement ‘sparkling clear’ Guardian ‘wonderfully concise, direct and to the point’ Times Literary Supplement ‘plays lightly and gracefully over . philosophical themes, including the relationship between good and living well.’ New Yorker Very Short Introductions are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide. The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology. Very Short Introductions available now: ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Continental Philosophy Julia Annas Simon Critchley THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE COSMOLOGY Peter Coles John Blair CRYPTOGRAPHY ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia Fred Piper and Sean Murphy ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn DADA AND SURREALISM ARCHITECTURE David Hopkins Andrew Ballantyne Darwin Jonathan Howard ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes Democracy Bernard Crick ART HISTORY Dana Arnold DESCARTES Tom Sorell ART THEORY Cynthia Freeland DRUGS Leslie Iversen THE HISTORY OF THE EARTH Martin Redfern ASTRONOMY Michael Hoskin EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY Atheism Julian Baggini Geraldine Pinch Augustine Henry -

A Cultural History of Tarot

A Cultural History of Tarot ii A CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAROT Helen Farley is Lecturer in Studies in Religion and Esotericism at the University of Queensland. She is editor of the international journal Khthónios: A Journal for the Study of Religion and has written widely on a variety of topics and subjects, including ritual, divination, esotericism and magic. CONTENTS iii A Cultural History of Tarot From Entertainment to Esotericism HELEN FARLEY Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Helen Farley, 2009 The right of Helen Farley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84885 053 8 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham from camera-ready copy edited and supplied by the author CONTENTS v Contents -

Britain Begins by Barry Cunliffe

“Britain Begins” by Barry Cunliffe – reviewed by Tom Shippey. Sir Barry Cunliffe CBE is Emeritus Professor of European Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, 36 Beaumont St, Oxford, OX1 2PG. His Research Interests are European archaeology especially in first millennium BC and early first millennium AD. Focusing on social and economic dynamics and the relationships between the Mediterranean world and 'barbarian' Europe. With Current Activities on Atlantic trade systems, cultural interaction and state formation in Southern Iberia and social hierarchies in Central Southern Britain. In addition to a number of site-specific monographs (including Porchester Castle, Bath, Fishbourne, Danebury etc) and recent Publications: Facing the Ocean (2001) and The Ancient Celts (1997).ustration by Clifford Harper/agraphia.co.uk. Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a scholar of medieval literature , including that of Anglo-Saxon England . ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Human or proto-human history in Britain goes back a long way. Flint debris, teeth and a shin bone from near Chichester have been dated back half a million years. Neanderthal teeth from near Rhyl are maybe half that old. A mere 30,000 years ago, people much like us buried one of their number, "the Red Lady of Paviland" (he was actually a man), in a cave in south Wales. Barry Cunliffe , then, has a great sweep to cover, which he does with usually unchallengeable authority. Yet most of the period of human inhabitation of Britain has little to do with who we are now. Some 13,000 years ago a dramatic drop in mean annual temperature – 15C in the space of a single generation – drove even the hardy hunters of Paviland and points north out of Britain entirely.