Hills, Dams and Forests. Some Field Observations from the Western Ghats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

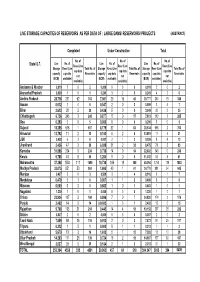

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

Final Project Completion Report

CEPF SMALL GRANT FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Organization Legal Name: - Tarantula (Araneae: Theraphosidae) spider diversity, distribution and habitat-use: A study on Protected Area adequacy and Project Title: conservation planning at a landscape level in the Western Ghats of Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka Date of Report: 18 August 2011 Dr. Manju Siliwal Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society Report Author and Contact 9-A, Lal Bahadur Colony, Near Bharathi Colony Information Peelamedu Coimbatore 641004 Tamil Nadu, India CEPF Region: The Western Ghats Region (Sahyadri-Konkan and Malnad-Kodugu Corridors). 2. Strategic Direction: To improve the conservation of globally threatened species of the Western Ghats through systematic conservation planning and action. The present project aimed to improve the conservation status of two globally threatened (Molur et al. 2008b, Siliwal et al., 2008b) ground dwelling theraphosid species, Thrigmopoeus insignis and T. truculentus endemic to the Western Ghats through systematic conservation planning and action. Investment Priority 2.1 Monitor and assess the conservation status of globally threatened species with an emphasis on lesser-known organisms such as reptiles and fish. The present project was focused on an ignored or lesser-known group of spiders called Tarantulas/ Theraphosid spiders and provided valuable information on population status and potential conservation sites in Uttara Kannada district, which will help in future monitoring and assessment of conservation status of the two globally threatened theraphosid species T. insignis and Near Threatened T. truculentus. Investment Priority 2.3. Evaluate the existing protected area network for adequate globally threatened species representation and assess effectiveness of protected area types in biodiversity conservation. -

Dams-In-India-Cover.Pdf

List of Dams in India List of Dams in India ANDHRA PRADESH Nizam Sagar Dam Manjira Somasila Dam Pennar Srisailam Dam Krishna Singur Dam Manjira Ramagundam Dam Godavari Dummaguden Dam Godavari ARUNACHAL PRADESH Nagi Dam Nagi BIHAR Nagi Dam Nagi CHHATTISGARH Minimata (Hasdeo) Bango Dam Hasdeo GUJARAT Ukai Dam Tapti Dharoi Sabarmati river Kadana Mahi Dantiwada West Banas River HIMACHAL PRADESH Pandoh Beas Bhakra Nangal Sutlej Nathpa Jhakri Dam Sutlej Chamera Dam Ravi Pong Dam Beas https://www.bankexamstoday.com/ Page 1 List of Dams in India J & K Bagihar Dam Chenab Dumkhar Dam Indus Uri Dam Jhelam Pakal Dul Dam Marusudar JHARKHAND Maithon Dam Maithon Chandil Dam Subarnarekha River Konar Dam Konar Panchet Dam Damodar Tenughat Dam Damodar Tilaiya Dam Barakar River KARNATAKA Linganamakki Dam Sharavathi river Kadra Dam Kalinadi River Supa Dam Kalinadi Krishna Raja Sagara Dam Kaveri Harangi Dam Harangi Narayanpur Dam Krishna River Kodasalli Dam Kali River Basava Sagara Krishna River Tunga Bhadra Dam Tungabhadra River, Alamatti Dam Krishna River KERALA Malampuzha Dam Malampuzha River Peechi Dam Manali River Idukki Dam Periyar River Kundala Dam Parambikulam Dam Parambikulam River Walayar Dam Walayar River https://www.bankexamstoday.com/ Page 2 List of Dams in India Mullaperiyar Dam Periyar River Neyyar Dam Neyyar River MADHYA PRADESH Rajghat Dam Betwa River Barna Dam Barna River Bargi Dam Narmada River Bansagar Dam Sone River Gandhi Sagar Dam Chambal River . Indira Sagar Narmada River MAHARASHTRA Yeldari Dam Purna river Ujjani Dam Bhima River Mulshi -

Proposed Action Plan for Rejuvenation of River Kali

ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF RIVER Kali ________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Proposed Action Plan for Rejuvenation of River Kali Karnataka State Pollution Control Board “Parisara Bhavana”, # 49, Church Street, Bengaluru - 560 001 January 2019 ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF RIVER Kali ________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDEX Topic Page No. Sl. No. 3-4 1 Introduction to Kali River 2 Sources of Pollution - Municipal Sewage 5 generation and Treatment 3 Characteristics of River water quality 6 4 Action taken by the Board 6 5 Action to be taken for Rejuvenation of River 6 Water Quality Cost component involved in the Restoration of 6 Polluted stretch 7 Status of Environmental Flow (E-Flow) 7 7-8 Short Term and Long Term Action and the 8 Identified Authorities for initiating actions and 8-12 the time limits for ensuring compliance ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF RIVER Kali ________________________________________________________________________________ 3 Proposed action plan for Rejuvenation of River Kali 09. State : Karnataka River Name: Kali River Stretch : Hasan Maad (west coast paper mill) to Bommanahalli Reservoir Priority : IV (BOD 6-10 mg/L) BOD Max.value: 6.5 mg/L ___________________________________________________________________ 1.The Kali river rises near Diggi, a small village in Joida taluk, Uttar Kannada district. The Kali River is flowing in part of 5 taluks out of 11 taluks through Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka State. The river is the lifeline to some four lakh peoples in the Uttara Kannada district and supports the livelihoods of thousands of people including fishermen on the coast of Karwar. There are many dams built across this river for the generation of electricity. -

Geographical Features of Karnataka

Class : B.A 5th Semester Subject : History & Archaeology Title of the Paper : History and Culture of Karnataka(From Early Times to 1336) Paper II Optional Session: 7,8 & 9. Topic : Geographical Features of Karnataka. __________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Karnataka State is situated in between 11.30 to 18.48 Northern latitude and 74.12 to 78.50 East longitude, Karnataka is surrounded by Maharashtra in North, Goa in Northwest, Tamilnadu & Keral in South, Andhara Pradesh & Telengana in East. Karnataka is 2000 feet above sea level. Present Karnataka is divided in to 30 Districts 230 Talukas 29733 Villages. The length of the state is 770 km and breadth is 400 km total extent of the State is 1,92,204 sq. km The main rivers of Karnataka is Krishna, Bhima, Tungabhadra, Malaprabha, Ghatprabha, Kali, Sharavati, Varadha, Kaveri, Netravati, Arkavati, Aghanashini etc. are the important rivers in the State. The region where two rivers joins is called as Doab. Shorapur Doab in Yadgiri district where river Bhima joins the Krishna. Raichur Doab where river Tungabhadra joins Krishna, the plateau of Raichur Doab & Tungabhdra referred as Rayalaseema. Geographical Classification of Karnataka 1. Coastal region 2. Sahyadri Mountains /Western Ghats 3. Northern Plain 4. Southern Plain Importance of Geographical Features : Richard Hakluyat, pointed out that “The Geography & Chronology are the Sun & Moon, the right and left eye of History”. Human history in a region is shaped by the physical features. The growth of civilization is depend upon the climate, fertility of soil, natural barriers. Geographically Karnataka is one of the oldest part of Deccan plateau. The history and culture of Karnataka has been molded by the Geographical features. -

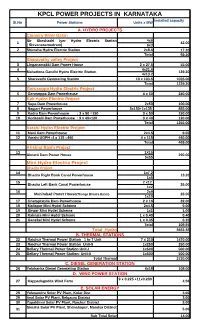

KPCL POWER PROJECTS in KARNATAKA Installed Capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units X MW

KPCL POWER PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA Installed capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units x MW A. HYDRO PROJECTS Cauvery River Basin Sir Sheshadri Iyer Hydro Electric Station 4x6 1 42.00 ( Shivanasamudram) 6x3 2 Shimsha Hydro Electric Station 2x8.6 17.20 Total 59.20 Sharavathy valley Project 3 Linganamakki Dam Power House 2 x 27.5 55.00 4 4x21.6 Mahathma Gandhi Hydro Electric Station 139.20 4x13.2 5 Sharavathi Generating Station 10 x 103.5 1035.00 Total 1229.20 Gerusoppa Hydro Electric Project 6 Gerusoppa Dam Powerhouse 4 x 60 240.00 Kali Hydro Electric Project 7 Supa Dam Powerhouse 2x50 100.00 8 Nagjari Powerhouse 5x150+1x135 885.00 9 Kadra Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 50 =150 3 x 50 150.00 10 Kodasalli Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 40=120 3 x 40 120.00 Total 1255.00 Varahi Hydro Electric Project 11 Mani Dam Powerhouse 2x4.5 9.00 12 Varahi UGPH :4 x 115 =460 4 x 115 460.00 Total 469.00 Krishna Basin Project 13 1X15 Almatti Dam Power House 290.00 5x55 Mini Hydro Electric Project Bhadra Project 14 1x7.2 Bhadra Right Bank Canal Powerhouse 13.20 1x6 15 2 x12 Bhadra Left Bank Canal Powerhouse 26.00 1x2 16 2x9 Munirabad Power House(Thunga Bhadra Basin) 28.00 1x10 17 Ghataprabha Dam Powerhouse 2 x 16 32.00 18 Mallapur Mini Hydel Scheme 2x4.5 9.00 19 Sirwar Mini Hydel Scheme 1x1 1.00 20 Kalmala Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.40 0.40 21 Ganekal Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.35 0.35 Total 109.95 Total Hydro 3652.35 B. -

Dams of India.Cdr

eBook IMPORTANT DAMS OF INDIA List of state-wise important dams of India and their respective rivers List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Dams are an important part of the Static GK under the General Awareness section of Bank and Government exams. In the following eBook, we have provided a state-wise list of all the important Dams in India along with their respective rivers to help you with your Bank and Government exam preparation. Here’s a sample question: In which state is the Koyna Dam located? a. Gujarat b. Maharashtra c. Sikkim d. Himachal Pradesh Answer: B Learning the following eBook might just earn you a brownie point in your next Bank and Government exam. Banking & REGISTER FOR A Government Banking MBA Government Exam 2017 Free All India Test 2 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) LIST OF IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA Andhra Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Nagarjuna Sagar Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Somasila Dam Penna Srisailam Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Arunachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Ranganadi Dam Ranganadi Bihar NAME OF THE DAM 2 RIVER Nagi Dam Nagi Chhattisgarh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Minimata (Hasdeo) Bango Dam Hasdeo Gujarat NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Kadana Dam Mahi Karjan Dam Karjan Sardar Sarover Dam Narmada Ukai Dam Tapi 3 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Himachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Bhakra Dam Sutlej Chamera I Dam Ravi Kishau Dam Tons Koldam Dam Sutlej Nathpa Jhakri Dam Sutlej Pong Dam Beas Jammu & Kashmir NAME -

– Kolab River 4)Indravati Dam – Indravati River 5)Podagada Dam – Podagada River 6)Muran Dam – Muran River 7)Kapur Dam – Kapur River

DAMS IN INDIA WEST BENGAL 1)FARRAKA BARRAGE – GANGES RIVER 2)DURGAPUR BARRAGE – DAMODAR RIVER 3)MAITHON DAM –BARAKAR RIVER 4)PANCHET DAM – DAMODAR RIVER 5)KANGSABATI DAM – KANGSABATI RIVER UTTAR PRADESH 1)RIHAND DAM – RIHAND RIVER 2)MATATILA DAM – BETWA RIVER 3)RAJGHAT DAM – BETWA RIVER ODISHA 1)HIRAKUND DAM – MAHANADI 2)RENGALI DAM – BRAHMANI RIVER 3)UPPER KOLAB DAMwww.OnlineStudyPoints.com – KOLAB RIVER 4)INDRAVATI DAM – INDRAVATI RIVER 5)PODAGADA DAM – PODAGADA RIVER 6)MURAN DAM – MURAN RIVER 7)KAPUR DAM – KAPUR RIVER www.OnlineStudyPoints.com DAMS IN INDIA JHARKHAND 1)MAITHON DAM- BARAKAR RIVER 2)PANCHET DAM- DAMODAR RIVER 3)TENUGHAT DAM – DAMODAR RIVER 5)GETALSUD DAM – SWARNAREKHA RIVER MADHYA PRADESH 1)GANDHISAGAR DAM – CHAMBAL RIVER 2)TAWA DAM – TAWA RIVER 3)INDIRA SAGAR DAM – NARMADA RIVER 4)OMKARESHWAR DAM – NARMADA RIVER 5)BARGI DAM – NARMADA RIVER 6)BARNA DAM – BARNA RIVER 7)BANSAGAR DAM – SON RIVER CHHATTISGARH www.OnlineStudyPoints.com 1)MINIMATA BANGO DAM – HASDEO RIVER 2)DUDHWA DAM – MAHANADI 3)GANGREL DAM – MAHANADI 4)SONDUR DAM – SONDUR 5)TANDULA DAM – TANDULA RIVER 6)MONGRA BARRAGE – SHIVNATH www.OnlineStudyPoints.com DAMS IN INDIA MAHARASHTRA 1)KOYNA DAM – KOYNA RIVER 2)JAYAKWADI DAM – GODAVARI RIVER 3)ISAPUR DAM – PENGANA RIVER 4)WARNA DAM – VARNA RIVER 5)TOTLADOH DAM – PENCH RIVER 6)SUKHANA DAM – SUKHANA RIVER 7)UJJANI DAM – BHIMA RIVER JAMMU AND KASHMIR 1)SALAL DAM – CHENAB RIVER 2)BAGLIHAR DAM – CHANAB RIVER 3)PAKUL DUL DAM – CHENAB RIVER 3)URI DAM – JHELUM RIVER 4)NIMBOO BAZGO HYDROELECTRIC PLANT – INDUS RIVER -

Tarantula (Araneae: Theraphosidae) Spider Diversity, Distribution and Habitat-Use in the Western Ghats of Uttara Kannada District, Karnataka

Tarantula (Araneae: Theraphosidae) spider diversity, distribution and habitat-use in the Western Ghats of Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka A study on Protected Area adequacy and conservation planning at a landscape level Dr. Manju Siliwal Wildlife Information Liaison Development Society 9-A, Lal Bahadur Colony, Gopalnagar, Peelamedu, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641004 Objectives • To understand patterns of species diversity, distribution and habitat use of theraphosid spiders across broad land use categories in Western Ghats of Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka - Protected areas, Reserve forest, Plantations, agriculture fields and settlement areas • To identify potential Conservation priority areas in Uttara Kannada district for Theraphosids. • To sensitize local people for conservation of tarantula spider Contributions towards CEPF investment strategy 2.1 Monitor and assess the conservation status of globally threatened species with an emphasis on lesser-known organisms such as reptiles and fish. • Two globally threatened species ( Poecilotheria striata and Thrigmopoeus insignis) were assessed for their population and threat status in the region during the study, and qualify for down-listing from Vulnerable to Near Threatened • Identified three sites (Kulgi, Potoli and Anshi) having high abundance of Taruntulas during the study, which areas are recommended for future monitoring of the spider populations 2.3 Evaluate the existing protected area network for adequate globally threatened species representation and assess effectiveness of protected -

Providing of One Number of Diesel Tata Indica Car Or Equivalent Make

Providing of one number of Diesel Tata Indica Car or equivalent make (White Colour & Non AC) of Model 2015 with driver, fuel and lubricants (POL) on hire basis for office duties of Superintending Engineer (Civil), KPCL, Ambikanagar for a period of two years & further one more year after satisfactory services from reputed bidders/ travel agencies. EXECUTIVE ENGINEER (MSP) A KARNATAKA POWER CORPORATION LIMITED AMBIKANAGAR- 581363 U.K DISTRICT KARNTAKA POWER CORPORATION LIMITED (A Government of Karnataka Enterprises) KALINADI HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT- STAGE-I Office of Executive Engineer (Machinery Stores Purchase) Ambikanagar Phone: 08284-258 681, Fax No: 08284-258640, Cell: 9449599113 Tender Notification No: KPCLA/CPS CAR-2015 DATE: 01.09.2015 Tenders in two covers are invited by Executive Engineer (MSP)A, KPCL Ambikanagar through “e” Procurement Portal (Website URL:https://eproc.karnataka.gov.in) for “Providing of one number of Diesel Tata Indica Car or equivalent make (White Colour & Non AC) of Model 2015 with driver, fuel and lubricants (POL) on hire basis for office duties of Superintending Engineer (Civil), KPCL, Ambikanagar for a period of two years & further one more year after satisfactory services from reputed bidders/ travel agencies.” 1.0 Instructions regarding e- procurement The bid is to be submitted in the GOK e-procurement platform www.eproc.karnataka.gov.in system only. Bidders, who have not registered in e-procurement portal, may do so by registering through web site www.eproc.karnataka.gov.in i. The Pre-qualified bidders can access bid documents on the web site, fill them and submit the completed bid documents in to electronic tender on the website itself within the stipulated date. -

Uttara Kannada.Xlsx

Sl. No. District Code District Taluk Code Taluk GP Code GP Amount 1 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001013 Achave 5862.00 2 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001015 Agragona 3874.00 3 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001016 Agsoor 9453.00 4 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001001 Alageri 5043.00 5 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001014 Avarsa 4868.00 6 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001005 Bobruwada 11296.00 7 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001006 Bhavikeri 7304.00 8 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001004 Belambar 7139.00 9 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001003 Belase 8550.00 10 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527002 Ankola 1527001007 Belekeri 5163.00 13 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001002 Dongri 4433.00 14 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001019 Harawada 4692.00 15 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001018 Hattikeri 4422.00 16 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001017 Hillur 6297.00 17 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001010 Mogata 3950.00 18 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001011 Sagadgeri 4198.00 19 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001009 Shetageri 5459.00 20 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001012 Sunkasala 3977.00 21 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527001 Ankola 1527001008 Vandige 8306.00 22 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527002 Bhatkal 1527002007 Bailur 8677.00 23 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527002 Bhatkal 1527002006 Beleke 2658.00 25 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527002 Bhatkal 1527002008 Bengre 4024.00 26 1527 Uttara Kannada 1527002 Bhatkal 1527002015 Hadavalli 14575.00