Johnny's” Entertainers Omnipresent on Japanese TV: Postwar Media and the Postwar Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

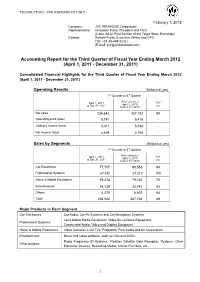

Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011)

TRANSLATION - FOR REFERENCE ONLY - February 1, 2012 Company: JVC KENWOOD Corporation Representative: Hisayoshi Fuwa, President and CEO (Code: 6632; First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Satoshi Fujita, Executive Officer and CFO (Tel: +81-45-444-5232) (E-mail: [email protected]) Accounting Report for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Consolidated Financial Highlights for the Third Quarter of Fiscal Year Ending March 2012 (April 1, 2011 - December 31, 2011) Operating Results (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) April 1, 2011 YoY April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Net sales 236,542 267,182 89 Operating profit (loss) 8,791 9,416 - Ordinary income (loss) 6,511 6,530 - Net income (loss) 4,409 2,193 - Sales by Segments (Millions of yen) 1st Quarter to 3rd Quarter (For reference) YoY April 1, 2011 April 1, 2010 to Dec.31, 2011 to Dec.31, 2010 (%) Car Electronics 77,707 80,558 96 Professional Systems 67,142 67,210 100 Home & Mobile Electronics 59,274 79,167 75 Entertainment 28,139 33,742 83 Others 4,279 6,502 66 Total 236,542 267,182 89 Major Products in Each Segment Car Electronics Car Audio, Car AV Systems and Car Navigation Systems Land Mobile Radio Equipment, Video Surveillance Equipment, Professional Systems Commercial Audio, Video and Display Equipment Home & Mobile Electronics Video Cameras, LCD TVs, Projectors, Pure Audio and AV Accessories Entertainment Music and video software, such as CDs and DVDs Radio Frequency ID Systems, Weather Satellite Data Reception Systems, Other Other projects Electronic Devices, Recording Media, Interior Furniture, etc. -

Penggemar Arashi Sebagai Pop Kosmopolitan

ADLN-PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA DAFTAR PUSTAKA Buku: Hills, Matt. 2002. Fan Cultures. New York: Routledge Jenkins, H. 2006. Pop Cosmopolitanism: Mapping Cultural Flows in an Age of Media Convergence. In Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York, NY: New York University Press. Kelly, William W. 2004. Fanning The Flames: Fans and Contemporary Culture. New York: State University of New York Lewis, Lisa A. 1992. The Adoring Audience: fanculture and popular media. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc. Moleong, Lexy J. (2007) Metodologi Penelitan Kualitatif. Bandung: PT Remaja Rosdakarya Ofset. Nagaike, Kazumi. 2012. Johnny‟s Idols as Icons: Female Desires to Fantasize and Consume Male Idol Images. In Patrick Galbraith (Ed.), Idols and Celebrities in Japanese Media Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Ruslan, Rosady. 2008. Metodologi Penelitian Public Relations dan Komunikasi. Jakarta: PT. Raja Grafindo Persada Stevens, C. S. 2004. Buying Intimacy: Proximity and Exchange at a Japanese Rock Concert. In William W. Kelly (Ed.), Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. New York: State University of New York Press. Stevens, C. S. (2008). Japanese Popular Music: Culture, Authenticity, and Power. London: Routledge Sugiyono. 2010. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif Kualitatif dan R & D. Bandung : Alfabeta Yano, C. R. 2004. Letters From The Heart: Negotiating Fan-Star Relationship in Japanese Popular Music. In William W. Kelly (Ed.), Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan. New York: State University of New York Press 87 SKRIPSI PENGGEMAR ARASHI SEBAGAI POP KOSMOPOLITAN.... RATU ADDINA YU'MINA ADLN-PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA Penelitian: 龐 惠潔 (2011) :「ファンコミュニティにおけるヒエラルキーの考察―台湾のジャ ニーズファンを例に―」 東京 東京大学 Anuar, R., Redzuan R. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Taking Note Cover Star

WHERE IS THE LOVE? The Story behind Japan’s Frozen Population Growth TAKING NOTE Global Perspectives and New Designs in Education COVER STAR Songstress May J Breaks Through with “Let It Go” ALSO: A Chocolate Movement Comes to Tokyo, Valentine’s Gift Guide, Art around Town, Agenda, Movies,www.tokyoweekender.com and more... FEBRUARY 2015 Your Move. Our World. C M Y CM MY CY Full Relocation CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management pets, vehicles Family programs Orientation and Cross-cultural programs Departure services Visa and Immigration Storage services Temporary accommodation Home and School search Asian Tigers goes to great lengths to ensure the highest quality service. To us, every move is unique. Please visit www.asiantigers-japan.com or contact us at [email protected] Customer Hotline: 03-6402-2371 FEBRUARY 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com Your Move. Our World. FEBRUARY 2015 CONTENTS 10 C MAY J. M How letting go and learning to love the Y cover song rekindled a music career CM MY CY Full Relocation 7 14 18 CMY K Services anywhere in the world. Asian Tigers Mobility provides a comprehensive end-to-end mobility service tailored to your needs. Move Management – office, households, Tenancy Management LEXUS TEST DRIVE TOKYOFIT BEAN-TO-BAR CHOCOLATE pets, vehicles Family programs Pernod Ricard Japan CEO Tim Paech takes Getting in touch with your inner child— Bringing a chocolate revolution -

Date April 26, 2013 Case Number 2009 (Wa) 26989 Court Tokyo

Date April 26, 2013 Court Tokyo District Court, Case number 2009 (Wa) 26989 47th Civil Division – A case in which the court found that the defendant's use of the photos of the plaintiffs, who are members of idol groups, in books without their authorization, infringed what is generally known as the publicity rights of the plaintiffs and is illegal under the tort law. In conclusion, the court upheld the plaintiffs' claims for an injunction against the publishing and sale of these books, and for the disposal of said books, and also partially upheld their claims for damages. In this case, the plaintiffs, who are members of idol groups, alleged that the defendant published and sold books while using the plaintiffs' photos in these books without their authorization, and thereby infringed their rights to exclusively use the customer appeal of their portraits, etc., as well as what is generally known as portrait rights. Accordingly, the plaintiffs sought an injunction against the publishing and sale of these books, demanded the disposal of said books, and claimed damages. In accordance with the gist of the judgment of the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of February 2, 2012, Minshu Vol. 66, No. 2, at 89, the court referred to a person's right to exclusively use the customer appeal of his/her own portrait, etc. as a publicity right and stated that this right is one of the rights derived from a right of personality. The court then held that "the unauthorized use of portraits, etc. of a person is considered to be infringement of the person's publicity right and is found to be illegal under the tort law if the sole purpose of the use is to take advantage of the customer appeal of the portraits, etc. -

El Colegio De México EL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES EN JAPÓN

El Colegio de México EL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES EN JAPÓN (1999 – 2008): CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA OFERTA A TRAVÉS DEL ESTUDIO DE UN CASO REPRESENTATIVO Tesis presentada por YUNUEN YSELA MANDUJANO SALAZAR en conformidad con los requisitos establecidos para recibir el grado de MAESTRÍA EN ESTUDIOS DE ASIA Y ÁFRICA ESPECIALIDAD JAPÓN Centro de Estudios de Asia y África 2009 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN……………………………………………………………………. 3 I. FENÓMENO IDOL EN JAPÓN Y OBJETO DE ESTUDIO………………... 14 1. Desarrollo general de la industria idol……………………………………. 14 2. Definición de idol………………………………………………………… 18 3. La compañía Johnny’s Jimusho………………………………………….. 22 4. Arashi…………………………………………………………………….. 31 II. ESTRATEGIAS DE DESARROLLO DEL MERCADO IDOL…………….. 36 1. Primera etapa: Base junior, reclutamiento y formación…………………. 37 2. Segunda etapa: Lanzamiento y consolidación de mercado………………. 46 3. Tercera etapa: Diversificación y expansión de mercado…………………. 58 III. SITUACIÓN ACTUAL DEL MERCADO DE IDOL VARONES………….. 68 1. El dominio idol dentro de la industria musical en Japón…………………. 69 2. Fin del monopolio y cambio de estrategias en el mercado de idol varones en Japón……………………………………………………………………… 75 CONCLUSIONES……………………………………………………………………. 84 REFERENCIAS………………………………………………………………………. 88 ANEXOS……………………………………………………………………………… 98 1 NOTA SOBRE EL SISTEMA DE ROMANIZACIÓN UTILIZADO En el presente estudio se utilizará, para los términos generales y los nombres de ciudades, el sistema de romanización usado en el Kenkyusha’s New Japanese – English Dictionary (3ra y ediciones posteriores). En el caso de nombres propios de origen japonés, se presentará primero el nombre y luego el apellido y se utilizará la romanización utilizada en las fuentes originales. Asimismo, es común que los autores no utilicen el macron (¯ ) cuando existe una vocal larga en este tipo de denominaciones. -

L'intertestualità Mediatica Del Johnny's Jimusho

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e civiltà dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea L’intertestualità mediatica del Johnny’s Jimusho Relatore Ch. Prof.ssa Maria Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof.ssa Paola Scrolavezza Laureando Myriam Ciurlia Matricola 826490 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 A papà. RINGRAZIAMENTI Ringrazio la mia famiglia: mio papà, che per anni e anni mi ha ascoltata mentre parlavo di Johnny’s , Yamapi, “Jin-l’odioso ” e di Giappone e passioni. Per aver sognato con me, sostenuto le mie scelte e aver avuto più fiducia in me di quanta ne abbia io. Alla mamma che mi ha costretta a giudicare oggettivamente le mie scelte, anche quando non volevo, e mi ha aiutata in cinque anni di studi fuori sede. Le mie cugine, Jessica, per la sua amicizia e Betty, per i suoi consigli senza i quali questa tesi oggi sarebbe molto diversa. Ringrazio mio nonno, per le sue premure e la sua pazienza quando dicevo che sarebbero passati in un baleno, quei mesi in Giappone o quell’anno a Venezia. La nonna, per il suo amore e le sue attenzioni. Le piccole Luna e Sally, per avermi tenuto compagnia dormendo sulle mie gambe quando studiavo per gli esami e per i mille giochi fatti insieme. Ringrazio le mie coinquiline: Ylenia, Caterina, Alessandra, Dafne, Veronica M. e Veronica F. Per le serate passate a guardare il Jersey Shore o qualche serie TV assurda e tutte le risate, la camomilla che in realtà è prosecco, le pulizie con sottofondo musicale, da Gunther a Édith Piaf. Per le chiacchierate fatte mentre si cucinava in quattro in una cucina troppo piccola, per le ciambelle alle sei del mattino prima di un esame e tutte le piccole gentilezze quotidiane. -

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin University of Tokyo, Japan Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Introduction, selection -

Artistas Começados Com a Letra "T" Não Encontrou O Artista Desejado? Oi Velox Internet 9.378 Artistas Envie Uma Letra De Música Dele! Internet Com Alta Velocidade

13/04/13 Listagem de artistas - letra T CIFRA CLUB PALCO MP3 FÓRUM NOTÍCIAS AUDIOWARE GUITAR BATTLE FORME SUA BANDA Entrar Músicas Artistas Estilos Musicais Playlists Promoções Destaques Mais O que você quer ouvir? buscar página inicial t artistas começados com a letra "T" Não encontrou o artista desejado? Oi Velox Internet 9.378 artistas Envie uma letra de música dele! Internet com Alta Velocidade. Planos de Até 15 Mega. Aproveite! oi.com.br/OiVelox ordem alfabética mais acessados adicionados recentemente busque por artistas na letra T Utilize o Gmail O Gmail é prático e divertido. Experimente! As Tall As Lions The Bride The Rednecks Tô de Boa É fácil e gratuito. Mail.Google.com As Tandinhas & Imagem.com The Bride Wore Black The Reds Tô De Tôka As Tchutchucas The Bridges The Redskins To Destination As Tequileiras The Briefs The Redwalls To Die For Curtir 4,1 milhões As Tequileiras do Funk The Briggs The Reepz To Dream of Autumn As The Blood Spills The Brighams The Reflection To Each His Own Seguir @letras As The Plot Thickens The Bright Light Social Hour The Refreshments To Elysium As the Sea Parts The Bright Road The Refugees To Fly As The Sky Falls The Bright Side The Regents To Have Heroes As The Sun Sets The Bright Star Alliance The Reign Of Kindo To Heart As The World Fades The Brightlife The Reindeer Section To Kill As They Burn The Brightwings The rej3ctz To Kill Achilles As They Sleep The Brilliant Green The Relationship Tó Leal As Tigresas The Brilliant Things The Relay Company To Leave A Trace As Tigresas do Funk The Brinners -

18483 19 18486 Ai 2017 Ai 18319 Ai 2031 Aiko 18580 Alan 18485

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA 18483 19 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA WATTE 18424 ABE SHIZUE MIZU IRO NO TEGAMI 18486 AI BELIEVE 2017 AI STORY 18319 AI YOU ARE MY STAR 5103 AI JOHJI & SHIKI CHINAMI AKAI GLASS 5678 AIKAWA NANASE BYE BYE 5815 AIKAWA NANASE SWEET EMOTION 5645 AIKAWA NANASE YUME MIRU SHOJYOJYA IRARENAI 2031 AIKO KABUTO MUSHI 2015 AKIKAWA MASAFUMI SEN NO KAZE NI NATTE 2022 AKIMOTO JUNKO AI NO MAMA DE 2124 AKIMOTO JUNKO AME NO TABIBITO 2011 AKIMOTO JUNKO MADINSON GUN NO KOI 18233 AKIMOTO JUNKO TASOGARE LOVE AGAIN 18562 AKIOKA SHUJI AIBOH ZAKE 2296 AKIOKA SHUJI OTOKO NO TABIJI 18432 AKIOKA SHUJI SAKE BOJO 18580 ALAN KUON NO KAWA 18485 ALAN NAMONAKI KOI NO UTA 5117 ALICE FUYU NO INAZUMA 2266 ALICE IMA WA MOH DARE MO 18279 AMANE KAORU TAIYOH NO UTA 5658 AMI SUZUKI ALONE IN MY ROOM 2223 AMIN MATSU WA 5340 AMURO NAMIE CAN YOU CELEBRATE 5341 AMURO NAMIE CHASE THE CHANCE 18536 AMURO NAMIE FIGHT TOGETHER 5711 AMURO NAMIE I HAVE NEVER SEEN 5766 AMURO NAMIE NEVER END 5798 AMURO NAMIE SAY THE WORD 5294 AMURO NAMIE STOP THE MUSIC 5820 AMURO NAMIE THINK OF ME 5300 AMURO NAMIE TRY ME (WATASHI O SHINJITE) 5838 AMURO NAMIE WISHING ON THE SAME STAR 18425 AN CAFÉ NATSU KOI NATSU GAME 18574 ANGELA AKI HOME 18296 ANGELA AKI KAGAYAKU HITO 18211 ANGELA AKI KISS ME GOODBYE 18224 ANGELA AKI RAIN 18552 ANGELA AKI SAKURA IRO 2360 ANGELA AKI TEGAMI ~ HAIKEI JUHGO NO KIMI E 2040 ANGELA AKI THIS LOVE 18358 ANGELA AKI WE'RE ALL ALONE 2258 ANN LEWIS GOODBYE MY LOVE 5494 ANN LOUISE WOMAN 2379 ANRI OLIVIA -

Billboard JAPAN HOT

2021年上半期チャート発表! 総合ソング・チャート1位は、優里「ドライフラワー」 総合アルバム・チャート1位は、SixTONES『1ST』 トップ・アーティストは、YOASOBIが受賞<各コメントあり> MRC Media, LLC.(本社所在地:ニューヨーク)のグループである「米国ビルボード」及び「 ビルボードジャパン」(日本におけるBillboardブランドのマスターライセンスを保有する株式会 社阪神コンテンツリンク)は、2021年上半期チャートの受賞楽曲・アーティストを発表いたしま す。(集計期間:2020年11月23日~2021年5月23日) 2021年上半期の総合ソング・チャート【Billboard JAPAN HOT 100】は、優里「ドライフラワ ー」が総合首位を獲得しました。「ドライフラワー」は2019年12月に配信された「かくれんぼ」 で歌われた「彼女」のその後を、女性目線で描いたアフターストーリー。集計期間内で累計スト リーミング回数が2億7,585万5,527再生を記録し、昨年度の年間首位に輝いたYOASOBI「夜に駆 ける」に続き、CDシングルのリリースがないにもかかわらず総合首位を制しました。そして2位 はLiSA「炎」、3位はBTS「Dynamite」が獲得。トップ3にはストリーミング、ダウンロード 、 動画再生といったデジタル領域でロングヒットを記録する楽曲が並びました。 総合アルバム・チャート【Billboard JAPAN HOT Albums】は、SixTONES『1ST』が首位を 獲得。集計期間中に572,074枚を売り上げた本作はデジタル配信されていないものの、CDセール ス1位、PC読み取り回数のルックアップで2位を記録して、見事トップに輝きました。続く2位は ダ ウ ン ロ ー ド 1 位 、 ル ッ ク ア ッ プ 1 位のYOASOBI『THE BOOK』 、 3 位はMr.Children『 SOUNDTRACKS』が獲得しました。 総合ソング・チャートと総合アルバム・チャートのポイントを合算したアーティスト・ランキ ング【Billboard JAPAN TOP Artists】では、目覚ましい活躍をみせるYOASOBIが首位に。 YOASOBIは“JAPAN HOT 100”トップ10に5曲がチャートインしており、楽曲だけではなく、ア ーティストとしての認知度も拡げました。 今年度の上半期では「うっせぇわ」が大きな話題を呼んだAdoを筆頭に、TiKTokやYouTubeに 代表される動画サービスを中心に活躍する新人アーティストがチャートを席巻。コロナ禍が続き 、音楽を“視聴”する習慣が定着したことで、多様な楽曲にアクセスできるようになり、ユーザー参 加型の楽曲が勢いを増しました。また、オンライン・ライブ市場も拡大しており、アフター・コ ロナを見据え、復興を目指す音楽業界のコンテンツとライブ市場を繋ぐ新たな光となることでし ょう。 各チャートの順位および優里、SixTONES、YOASOBIからの受賞コメントは、次をご覧くださ い。 優里 2021年上半期総合ソング1位獲得記念コメント 僕も毎週発表されるチャートを見て、こんなにたくさんの方が聴いてくれてるんだなと嬉しい 気持ちになりましたし、まさか上半期の1位になるだなんてまったく想像もしていませんでし た。すごくびっくりしていると同時に、とても嬉しいです。ありがとうございます。 SixTONES 2021年上半期総合アルバム1位獲得記念コメント 僕たちのファーストアルバム『1ST』というアルバムが“1ST”(1位)を頂き、本当に感謝で す。ありがとうございます。より多くの方々に僕たちの音楽を届ける事が、僕たちの一番の目