Tr Ransatl Lantic R Retailin Ng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[411000-AR] Datos Generales - Reporte Anual](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7947/411000-ar-datos-generales-reporte-anual-577947.webp)

[411000-AR] Datos Generales - Reporte Anual

Bolsa Mexicana de Valores S.A.B. de C.V. Clave de Cotización: GPH Año: 2020 Cantidades monetarias expresadas en Unidades [411000-AR] Datos generales - Reporte Anual Reporte Anual: Anexo N Oferta pública restringida: No Tipo de Instrumento: Acciones,Deuda LP Emisora extranjera: No Avalista El Palacio de Hierro, S.A. de C.V. Mencionar si cuenta o no con aval u otra garantía, especificar la Razón o Denominación Social: Mencionar dependencia parcial o total: No 1 de 143 Bolsa Mexicana de Valores S.A.B. de C.V. Clave de Cotización: GPH Año: 2020 Cantidades monetarias expresadas en Unidades [412000-N] Portada reporte anual GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, S.A.B. DE C.V. Durango 230, 2do. Piso, Col. Roma, Alcaldía. Cuauhtémoc, C.P. 06700, Ciudad de México, México. 2 de 143 Bolsa Mexicana de Valores S.A.B. de C.V. Clave de Cotización: GPH Año: 2020 Cantidades monetarias expresadas en Unidades Especificación de las características de los títulos en circulación [Sinopsis] Serie [Eje] serie Especificación de las características de los títulos en circulación [Sinopsis] Clase 1 Serie 1 Tipo Nominativa Número de acciones 377,832,983 Bolsas donde están registrados BOLSA MEXICANA DE VALORES, S.A.B. DE C.V. Clave de pizarra de mercado origen GPH1 Tipo de operación No aplica Observaciones No aplica Clave de cotización: GPH La mención de que los valores de la emisora se encuentran inscritos en el Registro: Los títulos se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores Leyenda artículo 86 de la LMV: La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad de los valores, solvencia de la emisora o sobre la exactitud o veracidad de la información contenida en este Reporte anual, ni convalida los actos que, en su caso, hubieren sido realizados en contravención de las leyes. -

Alpes De Haute-Provence

Alpes de Haute-Provence Here your desires take over! www.alpes-haute-provence.com 1 Contents A unique and contrasted place Page 3 Three major destinations Page 4 to 6 Haute Provence Luberon Verdon Alpes Mercantour The AHP are natural page 7 The AHP are sensory, fragrance maker pages 8 to 12 The scents and flavours complex The AHP are tasty, full-flavoured pages 13 to 14 The AHP are recreational (loisirs), athletic (sportives) pages 15 to 23 Outdoor activities Winter activities The AHP are rich of their cultural heritage pages 24 to 30 Excursions and Discovery Culture and heritage Festivities page 31 Festivals page 33 8 European « bests » page 35 Practical information & contacts page 36 2 A unique and contrasted Place The Alpes de Haute-Provence are located in the heart of the Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur region, on the Italian border and in the middle of the Marseille-Nice-Grenoble triangle. The « 04 » as it is called, between the Alps and Provence, is rich in spectacular and contrasting landscapes. A splendid light-filled natural environment blessed with an exceptional Provencal climate, three typical touristic areas each with their own features and traditions. It is one of the vastest French departments (6925 Km²) with quite small population density: 160 000 inhabitants. Most important towns are Digne- les-Bains, Manosque, Forcalquier, Sisteron, Barcelonnette, Gréoux-les- Bains, Oraison, Castellane, Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, Saint-André-les-Alpes, or Banon 146 mountain lakes Among them, the well-known Lac d’Allos, the biggest lake in Europe at this altitude (2226 m) as well as a fisherman’s paradise. -

Un Petit Tour Dans Les Hautes-Alpes A

ALAD Le Sauze- BARCELONNETTE Ü COL DE VARS Ü B E du-Lac COL D’IZOARD Ü BRIANÇON Ü Lac de Serre-Ponçon EMBRUN Ü BARCELONNETTE Pontis 195 km 3 h 30 D9 via Puy Sanière / Pontis Pont de Savines 7 14 km Partez à la découverte des villages authentiques du Queyras et de la Vallouise en passant par le col de Vars et le col Plaisir de conduite D954 d’Izoard. Une halte s’impose à Briançon place forte de Vauban, pour visiter son centre ancien escarpé. Puis longer Pleasure of riding D7 D954 Puy-Saint-Eusèbe la Durance, et revenir par une petite route en balcon qui vous permet de dominer le lac de Serre-Ponçon. M D900 O T O Itinéraire possible de juin à octobre. aneleLac Puy-Sanières 810 m Pont Roman au Lauzet-Ubaye Discover the authentic villages of the Queyras and Vallouise, passing through the Col de Vars and the Attrait touristique Izoard pass. A stop in Briançon, a Vauban fort stronghold, to visit its ancient and steep center. Then along Tourist attraction the Durance River, and return by a small balcony road which allows you to overlook Lake Serre-Ponçon. 42 km Attention, itinerary only possible from June to October. mbrun renre 849 m laee 15 km Cathédrale Notre-Dame d’Embrun N94 Les Thuiles Saint-Clément- 32 km Commune / Town À proximité / Near Route / Road Halte / Stopover Direction / Direction Distance / Distance sur-Durance N94 Saint-Martin- de-Queyrières ranon via D900, Saint-Crepin Barcelonnette Col de Vars Guillestre 61,6 km Eygliers Villar-Saint 1230 m D902 -Pancrace arcelonnee ullere 1135 m Col de Vars Vars Guillestre Arvieux D902 Col d’Izoard 18,3 km 2108 m D902 Cervières Col d’Izoard D902 Briançon 27,2 km 51 km Arvieux D900 Jausiers D902 Argentière-la- 20 km Briançon La Vieille Ville N94 46,4 km Saint-Paul-sur-Ubaye D902 La Condamine-Châtelard Equipment safety • Defensive driving = over pleasure and less than danger. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Emisión de Certificados Bursátiles GPH 19 | GPH 19-2 Presentación a Inversionistas Septiembre 2019 Aviso Legal Esta presentación fue preparada por Grupo Palacio de Hierro, S.A.B. de C.V. (“la Compañía”), exclusivamente para el uso establecido en la misma. Esta presentación fue preparada exclusivamente con propósitos informativos y no constituye compromiso alguno de compra o venta de instrumentos o activos financieros. No se contemplan representaciones o garantías expresas o implícitas para la precisión, afinación o integridad de la información presentada o contenida en esta presentación. La Compañía, ni sus afiliadas, consejeros o representantes o cualquiera de sus respectivos colaboradores acepta cualquier responsabilidad en lo que concierne a cualquier pérdida o daño resultante de cualquier información presentada o incluida en esta presentación. La información presentada o incluida en esta presentación es vigente a la fecha y está sujeta a cambios sin la obligación de la compañía de hacer notificaciones y su precisión no está garantizada. La Compañía, ni sus afiliadas, consejeros o representantes harán ningún esfuerzo para actualizar dicha información en lo sucesivo. Esta presentación no involucra temas legales, fiscales, financieros o de ningún otro tipo. Cierta información en esta presentación fue obtenida de diversas fuentes y la Compañía no verificó dicha información con fuentes independientes. Cierta información fue basada también en estimaciones de la Compañía. De acuerdo con esto, la Compañía no responde de la precisión o integridad de esa información o de las estimaciones de la Compañía y dicha información y estimados involucran riesgos e incertidumbre y son sujetos de cambio basados en factores varios. 2 Presentadores . -

Guide-Du-Velo.Pdf

FRANCE - ALPES DU SUD FR EN THE SOUTHERN ALPS CYCLING Competive spirit ESPRIT VAGABOND OU DE COMPÉTITION ? or a desire to roam? The Ubaye Valley EN UBAYE, LE VÉLO S’ADAPTE À TOUTES has something VOS ENVIES ! for everyone! Seven cols overlook the Ubaye, an Sept cols de haute-montagne toisent l’Ubaye, vallée préservée des Alpes du Sud, de leur > Une signalétique unspoilt valley in the southern Alps. solitude minérale. On les dit mythiques et pour cause : le Tour de France les a sillonnées adaptée... Chez nous, Described as legendary, and with les bornes kilométriques good reason : the Tour de France has plusieurs dizaines de fois, et de grands coureurs s’y sont cassé les dents, de Poulidor à parlent ! Altitude, kilomètres passed through dozens of times and depuis Barcelonnette Eddy Merckx, jusqu’à Stefan Schumacher, en 2008. Au centre de ce cirque de pierre, à parcourir, pourcentage de la many big names have come unstuck la ville de Barcelonnette se pose en capitale. Au départ de ses rues pavées et de ses pente... Autant d’informations here, from Poulidor to Eddy Merckx, right up to Stefan Schumacher in 2008. Cycling « à la carte » placettes animées, 4 000 km de circuits en étoile et d’itinéraires de cyclotourisme capitales qui aident les cyclistes à doser leurs efforts lors de At the centre of this circle of peaks, from Barcelonnette s’offrent à vous, de la frontière italienne au lac de Serre-Ponçon. Faites le plein d’oxygène l’ascension des cols et des the town of Barcelonnette is the val- en partant à la découverte des richesses naturelles et culturelles de l’Ubaye.. -

Hotels Et Chambre D'hotes Huate Provence

Alpes de Haute-Provence Here your desires take over! Where to sleep HAUTE PROVENCE BEDS & BREAKFAST The Relais d'Elle in Niozelles 5 rooms and resident meals Between the Luberon and the montagne de Lure, this old bastide restored by Catherine Pensa offers a shady haven of peace and quiet. The swimming pool and terrace in the shade of the trees enable visitors to make the most of a magnificent view over the hills of the Pays de Forcalquier. 04 92 75 06 87 www.relaisdelle.com Le mas de la Rabassière in Pierrerue Peace and quiet guaranteed in the one large room available in this XVIIth-century stone Mas, between lavender fields and olive groves, with a sweeping view of the Luberon, the montagne de Lure and the Alps. 04 92 75 25 46 / 06 15 13 85 31 [email protected] Les "Vieux Murs" in Montfort When your first name is Pierre, and your surname Laroche, and you live in Montfort, "les vieux murs" (old walls) is an obvious choice of name for your house. Between Sisteron and Manosque, the gateway to the Alpes de Haute Provence, this is a delightful stop. The charming village house is reached on a road which winds through the olive trees. Located in the middle of a small hilltop village, "Vieux Murs" is filled with an indefinable charm which owes as much to the warm but sophisticated decoration of the 2 rooms as to the courteous and discreet welcome of the owners. There is a small pool for the guests to keep cool in with an incredible view of the Pénitents des Mées, a geological curiosity overlooking the Durance valley. -

TRADE MISSION Mexico City & Monterrey, Mexico June 11 - 16, 2017

IHA MEXICO TRADE MISSION Mexico City & Monterrey, Mexico June 11 - 16, 2017 ake part in an IHA/International Business Council (IBC) Trade Mission for a turn-key Tintroduction to an international market. Meetings, retail tours, receptions, transportation and hotel details are scheduled in advance, allowing you to focus on your business rather than the logistical details. Trade missions also allow for extensive networking with other industry participants who share common interests and goals. Join the IHA-IBC Trade Mission to meet buyers in Mexico City and Monterrey to increase international sales into the Mexican market. Through retailer and distributor meetings and retail tours, participants will receive a thorough understanding of this key market and obtain a personal network of key home and housewares retailers. SCHEDULE (SUBJECT TO CHANGE) Targeted retailers in Mexico City include: Saturday, June 10 ..........Arrive in Mexico City Amazon Mexico Sunday, June 11 .............Retail Tour Monday, June 12 ............One-on-one Retailer Meetings Casa Palacio / El Palacio de Hierro Tuesday, June 13 ...........One-on-one Retailer Meetings Wednesday, June 14 ......Fly to Monterrey The Home Store Wednesday, June 14 ......Retail Tour Idea Interior / Ideas Thursday, June 15 .........One-on-one Retailer Meetings Domésticas Friday, June 16 ..............One-on-one Retailer Meetings Liverpool Saturday, June 17 ..........Depart Monterrey Sears Tiendas Chedraui Targeted retailers in Monterrey include: Famsa HEB Mexico Home Depot Mexico Lowe’s Mexico Soriana “Participating in the IHA Trade Mission clearly enhanced our credibility with customers. It opened new doors for us and accelerated business development with existing customers. The ability to follow up in person with buyers who had visited us at the International Home + Housewares Show was invaluable. -

American Girl® Expands Into Mexico

October 30, 2014 American Girl® Expands into Mexico — Company to Open Three American Girl Shop-in-Shop Boutiques in 2015 with El Palacio de Hierro, Mexico's largest high-end retailer— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- American Girl, a division of Mattel, Inc. (NASDAQ:MAT), today announced its expansion into Mexico in partnership with El Palacio de Hierro, Mexico's largest and best-established high-end retailer. The first two American Girl shop-in-shop boutiques will open in summer 2015 at El Palacio de Hierro's Perisur and Interlomas locations in Mexico City, followed by a third boutique at the Polanco location in fall 2015. "For nearly 30 years, American Girl has been celebrating and encouraging girls to be their best with high-quality dolls and engaging books and entertainment. Today, we're thrilled to bring the American Girl experience into Mexico—our second international location—and inspire a whole new group of girls to stand tall, reach high, and dream big," said Jean McKenzie, executive vice president of American Girl. "We're equally enthusiastic about partnering with such a well-respected retailer as El Palacio de Hierro. Its rich heritage and positive reputation for creating premium experiences offers an ideal way to introduce American Girl to girls and their families in Mexico." "We are excited to become American Girl's exclusive partner for the Mexican market, launching for spring 2015. We have an aggressive growth strategy for the next years, launching not only shop-in-shop boutiques but a whole experience for the Mexican girls. I truly believe that the American Girl concept and its exceptional value will resonate with the Mexican consumer," said Ernesto Izquierdo, commercial director from El Palacio de Hierro. -

In Some Respects, We Go Down Parallel Tracks Because the More

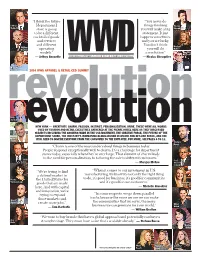

“I think the future “You never do Jeffrey [department] things thinking Nicolas Gennette store is going you will make a big Ghesquière to be a di erent statement. It just cocktail of goods happens sometimes and services and you are lucky. and di erent You don’t think William Marigay Bratton operating you will do McKee Chip models.” a revolution.” Bergh — Jeffrey Gennette WWDWEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2014 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY — Nicolas Ghesquière Michelle revolutionGloeckler 2014 WWD APPAREL & RETAIL CEO SUMMIT John Spelich NEW YORK — CREATIVITY. CHARM. PASSION. INSTINCT. PERSONALIZATION. DRIVE. THESE WERE ALL WORDS evolutionUSED BY FASHION AND RETAIL EXECUTIVES GATHERED AT THE PIERRE HOTEL HERE AS THEY DISCUSSED SUBJECTS INCLUDING THE GROWING MADE IN THE USA MOVEMENT, THE CREATIVE FORCE, THE FUTURE OF THE David DEPARTMENT STORE, THE INDUSTRY’S INCREASING GLOBALIZATION IN ONLINE AND OFF-LINE RETAIL, AND THE Walker- VITAL NEED TO INSPIRE EVERYONE FROM THE CONSUMER TO THE EMPLOYEE. FOR MORE, SEE PAGES 4 TO 12. Smith Stefano Rosso “Charm is one of the most undervalued things in business today. People respond exceptionally well to charm. It’s a challenge for department stores today, especially when they’re very large. That element of charm leads to the need for personalization, to tailoring the sale to di erent customers.” Rick José Caruso — Marigay McKee de Jesús Legaspi “We’re trying to fi nd “When it comes to our investment in U.S. a defi ned market in manufacturing, we know it’s not only the right thing Deena the United States for to do, it’s good for business, it’s good for communities Varshavskaya and it’s good for our customers.” Christina goods that are made Mercando here. -

Irresistible GB.Indd

PRESS KIT « I’m off now » ALPES DE HAUTE PROVENCE 2020 « The day you set o is the day the sun shines bright ». Jean GIONO The Alpes de Haute Provence is all of these : Health, nature, culture, quality of life and exceptional landscapes : tourism is a key strategic sector for the depart- ment. It generates a large number of jobs, incomes and added value for the other economic sectors. It plays an important role in the spatial planning of the Alpes de Haute Provence. In the heart of the Région Sud – Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur ! We are at a crossroads… less than one hour from the Hiking 6,600 km of marked trails Mediterranean, the French Riviera, Nice, Marseille, Avignon, Briançon and a stone’s throw from Italy…. We are located in the Unesco Heritage Alpes-Maritimes, Var, Bouches-du-Rhône, Vaucluse and Hautes-Alpes departments ! Luberon Nature Regional Park Haute Provence Geopark And people even like to say that the sky seems so near that we can touch the stars. Thermalism and well-being Vauban fortification heritage Gréoux-les-Bains : 35,000 spa clients Roman bridges in Annot and Céreste Digne-les-Bains : 6,000 spa clients Roman bridges in Lurs and Ganagobie Winter Sports A reference territory for fragrances 9 alpine ski resorts and 6 Nordic skiing sites Cosmetics 16.5 to 18 million Euros ski lift turnover (average over 6925 km£ : one of the biggest departments in France 33 firms, 770 salaried workers and an internationally last 5 years) 162, 000 inhabitants famous leader, L’Occitane en Provence 260 metres : the lowest point, in the Durance valley 3,412 metres : the highest point, in the Alps (Aiguille du Chambeyron) An exceptional natural heritage A reference territory for flavours The largest canyon in Europe, The agri-food industry represents 160 firms and 1,500 2.5 million tourists The biggest high mountain lake in Europe, jobs. -

INFORME-ANUAL-2020.Pdf

20 20 “La fortaleza financiera de Grupo Palacio de Hierro le ha permitido mantener su amplia solvencia —y lo digo con orgullo—, el empleo y la remuneración de nuestros colaboradores”. “The solid finances of Grupo Palacio de Hierro have enabled us to maintain a wide solvency, in addition to —and I say this with pride—, safeguarding our employees’ jobs and salaries”. Licenciado Alberto Baillères El Palacio de Hierro Polanco 6 INFORME ANUAL | ANNUAL REPORT 2020 7 11 89 INFORME DEL CONSEJO A LA ASAMBLEA LOGÍSTICA | REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS TO THE ASSEMBLY | LOGISTICS 31 95 GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO FINANZAS | GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO | FINANCE • TRANSFORMACIÓN | TRANSFORMATION • CONSTRUYENDO EL EQUIPO DEL FUTURO | BUILDING THE TEAM OF THE FUTURE • RESPONSABILIDAD SOCIAL 102 | SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY CONSEJO DE ADMINISTRACIÓN • RELACIONES CON CLIENTES | BOARD OF DIRECTORS | CUSTOMER RELATIONS 104 61 DIRECTORIO DIVISIÓN COMERCIAL DE NEGOCIO | DIRECTORY | COMMERCIAL DIVISION • EL LUJO EN EL PALACIO DE HIERRO | THE LUXURY IN EL PALACIO DE HIERRO • MODA: PILAR DE CRECIMIENTO | FASHION: GROWTH PILAR • CASA PALACIO, HOGAR Y TECNOLOGÍA | CASA PALACIO, HOME AND TECHNOLOGY • BOUTIQUES Y DEPORTES: REINVENTANDO LAS FORMAS DE VENDER | BOUTIQUES AND SPORTS: REINVENTING SALES CHANNELS • COMERCIO ELECTRÓNICO | E-COMMERCE GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, SAB DE CV INFORME ANUAL DEL CONSEJO DE ADMINISTRACIÓN A LA ASAMBLEA DE ACCIONISTAS, CORRESPONDIENTE AL EJERCICIO FISCAL DE 2020 GRUPO PALACIO DE HIERRO, SAB DE CV COMPANY PERFORMANCE REPORT -

Mercantour National Park

Council of Europe Conseil de I'Europe * * * * * * * **** * Strasbourg, 2 February 1998 PE-S-DE (98) 60 [s:\de98'docs\de60E.98] COMMITTEE FOR THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE IN THE FIELD OF BIOLOGICAL AND LANDSCAPE DIVERSITY CO-DBP Group of specialists- European Diploma Mercantour National Park (France) Category A RENEWAL Expertise report Mr Alfred FROMENT (Belgium) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribue en reunion. Priere de vous munir de cet exemplaire. PE-S-DE (98) 60 - 2 - The Secretariat did not accompany the expert during his visit to the park. Resolution (93) 21, awarding the European Diploma, is reproduced in Appendix I; in Appendix II, the Secretariat presents a draft resolution for possible renewal in 1998. - 3- PE-S-DE (98) 60 1. INTRODUCTION As the European Diploma awarded to the Mercantour National Park. (PNM) is due to expire on 3 May 1998, an expert appraisal to examine whether it should be renewed was carried out, in confonnity with current regulations. This appraisal took place on 2 and 3 September 1997. The expert was accompanied throughout his visit by Ms M-0. GUTH, Director, and Mr G. LANDRIEU, new Deputy Director. The expert was satisfied with the open and constructive nature of the discussions during his two-day visit. The trade union delegation (MM J.-M. CULOTTA and C. JOULOT) was interviewed at the expert's request, mainly concerning the management problem posed by the return of the wolf. The expert also discussed this subject with Ms FL.