20091214 Ontario Superior Court of Justice Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

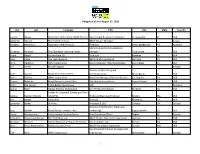

Condensed 8-27-16 Delegate List for Website

Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Lauren Alleva World Golf Hall of Fame IMAX Theater Marketing & Promotions Manager St. Augustine FL USA Abdullah Alshtail The Scientific Center IMAX Theater Manager Kuwait Stephen Amezdroz December Media Pty Ltd Producer South Melbourne VIC Australia Marketing and Communications Christina Amrhein The Challenger Learning Center Manager Tallahassee FL USA Violet Angell Golden Gate 3D Producer Berkeley CA USA John Angle The Tech Museum IMAX Chief Projectionist San Jose CA USA Chris Appleton IMAX Corporation Senior Manager, Aftermarket Sales Los Angeles CA USA Tim Archer Masters Digital Canada Director of Marketing and Katie Baasen McWane Science Center Communications Birmingham AL USA Doris Babiera IMAX Corporation Associate Manager, Film Distribution Los Angeles CA USA Shauna Badheka MacGillivray Freeman Films Distribution Coordinator Laguna Beach CA USA Peter Bak-Larsen Tycho Brahe Planetarium CEO Denmark Janine Baker nWave Pictures Distribution Snr VP Film Distribution Burbank CA USA Center for Science & Society and Twin JoAnna Baldwin Mallory Cities PBS Producer/Executive Producer Boston MA USA Jim Barath Sonics ESD Principal Monterey CA USA Jonathan Barker SK Films President & CEO Toronto ON Canada Director of Distribution Media and Chip Bartlett MacGillivray Freeman Films Technology Laguna Beach CA USA Sandy Baumgartner Saskatchewan Science Centre Chief Executive Officer Regina SK Canada Samantha Belpasso-Robinson The Tech Museum IMAX Theater Operations Supervisor San Jose CA USA Amanda Bennett Denver Museum of Nature & Science Marketing Director Denver CO USA Jenn Bentz Borcherding Pacific Science Center IMAX Projectionist Supervisor Seattle WA USA Vice President Product Development Tod Beric IMAX Corporation Engineering Mississauga ON Canada 1 Delegate List as of August 27, 2016 First Last Company Title City State Country Jonathan Bird Oceanic Research Group, Inc. -

9. IMAX Technology and the Tourist Gaze

Charles R. Acland IMAX TECHNOLOGY AND THE TOURIST GAZE Abstract IMAX grew out of the large and multiple screen lm experiments pro- duced for Expo ’67 in Montréal. Since then, it has become the most suc- cessful large format cinema technology.IMAX is a multiple articulation of technological system, corporate entity and cinema practice. This article shows how IMAX is reintroducing a technologically mediated form of ‘tourist gaze’, as elaborated by John Urry,into the context of the insti- tutions of museums and theme parks. IMAX is seen as a powerful exem- plar of the changing role of cinema-going in contemporary post-Fordist culture, revealing new congurations of older cultural forms and practices. In particular,the growth of this brand of commercial cinema runs parallel to a blurring of the realms of social and cultural activity,referred to as a process of ‘dedifferentiation’. This article gives special attention to the espistemological dimensions of IMAX’s conditions of spectatorship. Keywords cinema; epistemology; postmodernism; technology; tourism; spectatorship Technologies and institutional locations of IMAX N E O F T H E rst things you notice at the start of an IMAX lm, after the suspenseful atmosphere created by the mufed acoustics of the theatre, andO after you sink into one of the steeply sloped seats and become aware of the immense screen so close to you, is the clarity of the image. As cinema-goers, we are accustomed to celluloid scratches, to dirty or dim projections, and to oddly ubiquitous focus problems. The IMAX image astonishes with its vibrant colours and ne details. -

Paramount Pictures' 3-D Movie Transformers: Dark of The

PARAMOUNT PICTURES’3 -D MOVIE TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON LAUNCHES BACK INTO IMAX® THEATRES FOR EXTENDED TWO-WEEK RUN Film Grosses $1,095 Billion to Date Los Angeles, CA (August 23, 2011) – IMAX Corporation (NYSE:IMAX; TSX:IMX) and Paramount Pictures announced today that Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the third film in the blockbuster Transformers franchise, is returning to 246 IMAX® domestic locations for an extended two-week run from Friday, Aug. 26 through Thursday, Sept. 8. During those two weeks, the 3-D film will play simultaneously with other films in the IMAX network. Since its launch on June 29, Transformers: Dark of the Moon has grossed $1,095 billion globally, with $59.6 million generated from IMAX theatres globally. “The fans have spoken and we are excited to bring Transformers: Dark of the Moon back to IMAX theatres,”said Greg Foster, IMAX Chairman and President of Filmed Entertainment. “The film has been a remarkable success and we are thrilled to offer fans in North America another chance to experience the latest chapter in this history making franchise.”Transformers: Dark of the Moon: An IMAX 3D Experience has been digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology for presentation in IMAX 3D. The crystal-clear images, coupled with IMAX’s customized theatre geometry and powerful digital audio, create a unique immersive environment that will make audiences feel as if they are in the movie. About Transformers: Dark of the Moon Shia LaBeouf returns as Sam Witwicky in Transformers: Dark of the Moon. -

Estta1050036 04/20/2020 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1050036 Filing date: 04/20/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91254173 Party Plaintiff IMAX Corporation Correspondence CHRISTOPHER P BUSSERT Address KILPATRICK TOWNSEND & STOCKTON LLP 1100 PEACHTREE STREET, SUITE 2800 ATLANTA, GA 30309 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 404-815-6500 Submission Motion to Amend Pleading/Amended Pleading Filer's Name Christopher P. Bussert Filer's email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Christopher P. Bussert/ Date 04/20/2020 Attachments 2020.04.20 Amended Notice of Opposition for Shenzhen Bao_an PuRuiCai Electronic Firm Limited.pdf(252165 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the matter of Application Serial No. 88/622,245; IMAXCAN; Published in the Official Gazette of January 21, 2020 IMAX CORPORATION, ) ) Opposer, ) ) v. ) Opposition No. 91254173 ) SHENZHEN BAO’AN PURUICAI ) ELECTRONIC FIRM LIMITED, ) ) Applicant. ) AMENDED NOTICE OF OPPOSITION Opposer IMAX Corporation (“Opposer”), a Canadian corporation whose business address is 2525 Speakman Drive, Sheridan Science and Technology Park, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1, believes that it will be damaged by registration of the IMAXCAN mark as currently shown in Application Serial No. 88/622,245 and hereby submits this Amended Notice of Opposition pursuant to 37 C.F.R. §2.107(a) and Fed. R. Civ. P. 15, by which Opposer opposes the same pursuant to the provisions of 15 U.S.C. -

Event Program

EVENT PROGRAM TWITTER: #GSCA GIANTSCREENCINEMA.COM Program sponsored by i ii NTS TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS TA GSCA Contacts Giant Screen Cinema Association 624 Holly Springs Road, Suite 243 Holly Springs, NC 27540 U.S. giantscreencinema.com 2 Thank You to Our Sponsors facebook.com/giantscreencinema twitter.com/gsca 4 Schedule Find our group on LinkedIn 7 Event Map Tammy Seldon Executive Director 8 New Films Office: 1-919-346-1123 14 Films in Production Mobile: 1-703-855-3699 [email protected] Projects in Development 22 Kelly Germain Director of Membership and 28 Symposium Sessions Communications 30 Session Presenters Office: 1-651-917-1080 Mobile: 1-651-270-4915 [email protected] Advertiser Index Eileen Pheiffer 3D Entertainment Distribution inside front cover Accounting American Museum of Natural History 15 Office: 1-314-725-7020 Mobile: 1-314-708-0448 FotoKem 3 [email protected] Christie 27 GSCA 2, inside back cover ImagesInSound 25 IMAX Corporation 17, back cover Jackson Hole Wildlife Film Festival 40 MacGillivray Freeman Films 20, 21 nWave Pictures Distribution 11 1 YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK With Thanks to Our Event Sponsors Policies PLATINUM SPONSOR Recording and Media Policies Event sessions may be recorded. Audience members are advised that attendance at these sessions gives GSCA their implicit permission to be recorded. Private video or audio recording during film presentations GOLD SPONSOR or professional development sessions is prohibited without prior authorization from GSCA. Industry press has access to all sessions and events. GSCA will not be held responsible for any delegate commentary made in the presence of press/media. -

HUBBLE 3D Production Notes 2 24 10

Through the power of IMAX ® 3D, “Hubble 3D,” narrated by Leonardo DiCaprio, takes moviegoers on an unprecedented voyage through distant galaxies to explore the grandeur and mystery of our celestial surroundings. Experience never-before-seen 3D flights through the farthest reaches of the universe, and accompany spacewalking astronauts on some of the most difficult and important endeavors in NASA’s history. In May 2009, the crew of the Space Shuttle Atlantis launched a mission to make vital repairs and upgrades to the Hubble Space Telescope, the world’s first space-based observatory, 350 miles above the Earth. On board was an IMAX 3D camera, operated by the shuttle astronauts. It captured stunning sequences of the five intricate spacewalks required to make those repairs, as well as close-up images of the effort to grasp the orbiting telescope with the shuttle’s mechanical arm at 17,500 mph, and one unexpected problem that threatened to sabotage the entire mission. “Hubble 3D” combines this breathtaking IMAX footage with images taken by the telescope during the nearly 20 years it has been our window into space. Through advanced computer visualization, Hubble’s detailed data becomes a series of scientifically realistic flights that unfold on screen like a guided tour of the universe, through time and space. The seventh film from the award-winning IMAX Space Team, “Hubble 3D” offers an inspiring and unique look into the legacy of the Hubble Space Telescope and how it has changed our view of the universe and ourselves. The documentary adventure “Hubble 3D” is an IMAX and Warner Bros. -

Imax Annual Report 2021

Imax Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NYSE:IMAX) Published: March 4th, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file Number 001-35066 IMAX Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Canada 98-0140269 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 2525 Speakman Drive, 902 Broadway, Floor 20 Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1 New York, New York, USA 10010 (905) 403-6500 (212) 821-0100 (Address of principal executive offices, zip code, telephone numbers) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Shares, no par value IMAX The New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Imax: Expansion in Bric Economies (Revised)

9B15M028 1 IMAX: EXPANSION IN BRIC ECONOMIES (REVISED) Dwarka Chakravarty wrote this case under the supervision of Professor Paul W. Beamish solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) [email protected]; www.iveycases.com. Copyright © 2015, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation Version: 2016-08-26 In September 2013, Richard Gelfond, chief executive officer of IMAX Corporation (IMAX), declared that the route to becoming a billion-dollar company lay in growth markets outside of North America.2 This was no “blue sky envisioning,” but a pragmatic view grounded in facts. These included competition from U.S. exhibitors offering an “IMAX-like” experience, and a flat five year box office trend in North America versus double digit growth in Asia Pacific and Latin America. In 2013, for the first time in four decades, IMAX aggregate revenue from 56 countries outside of the United States and Canada ($151 million,3 10 per cent growth from 2012) exceeded North American revenues ($137 million, 6.5 per cent decline from 2012). -

IMAX CORPORATION 2525 Speakman Drive Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1 Tel: (905) 403-6500 Fax: (905) 403-6450

IMAX CORPORATION 2525 Speakman Drive Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1 Tel: (905) 403-6500 Fax: (905) 403-6450 www.imax.com THE MONKEY KING 2 ACHIEVES ESTIMATED $10.7 MILLION FOR RECORD OPENING WEEKEND AT CHINESE BOX OFFICE IN IMAX® 3D THEATRES Sequel Sets New Box Office Record for IMAX During Chinese New Year Holiday SHANGHAI – Feb. 14, 2015 – IMAX Corporation (NYSE: IMAX) and IMAX China (HKSE: 1970) today announced that The Monkey King 2, the 3D adventure-fantasy film from director Pou-Soi Cheang, earned approximately $10.7 million during its opening week in China on 279 IMAX screens, making it the highest opening for a Chinese IMAX DMR® (Digitally Re-mastered) film during the Chinese New Year holiday. Launching in China on Feb. 8, The Monkey King 2 also scored the largest-ever opening-day gross for a local-language film in IMAX, with $2.4 million. The Monkey King 2, from Filmko Pictures, surpassed last year’s Dragon Blade, which previously held the record for the largest opening-week gross during Chinese New Year, with $7.3 million. “What a way to kick off the Chinese New Year holiday season at the box office,” said Greg Foster, Senior Executive Vice President, IMAX Corp. and CEO of IMAX Entertainment. “We extend a huge congratulations to our partners at Filmko Pictures and visionary director Pou-Soi Cheang on this record- setting IMAX opening for The Monkey King 2. There is clearly a strong demand among Chinese moviegoers to experience thrilling and entertaining cinema in IMAX 3D, and we look forward to this film’s continued success throughout China in IMAX.” The IMAX® 3D release of The Monkey King 2 will be digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology. -

IMAX and AMC Entertainment Expand Joint Venture Relationship for Up

IMAX And AMC Entertainment® Expand Joint Venture Relationship For Up To 25 New IMAX® Theatres Expansion & Extension of Previous Deal Adds to AMC's Leading IMAX Presence in North America New Agreement Calls for Minimum of 15 Theatres, with Potential for Up to 25 New Theatres Planned to Open in Both Untapped IMAX Markets and Existing AMC IMAX Markets in North America New York, N.Y. and Kansas City, Mo. - June 1, 2010 - IMAX Corporation (NASDAQ: IMAX; TSX: IMX) and AMC Entertainment (AMC), today announced an expansion of the companies' joint venture agreement to include installation of between 15 and 25 new IMAX® theatres in the United States. These theatres, which are part of an amendment to the parties' original 2007 joint venture agreement, are in addition to AMC's current roll-out of 104 IMAX joint venture theatres, 79 of which are in operation and 25 of which are expected to open by the end of 2010 in the United States and Canada. The companies intend to open the 15 to 25 new IMAX theatres in 2011 in both new markets and some markets where AMC already operates IMAX theatres in North America. Upon completion of the full AMC IMAX theatre roll-out, AMC will operate between 125 and 135 IMAX theatres. "We are pleased to expand our relationship with IMAX, a valued partner in offering our guests the best out-of-home entertainment experience," said Gerry Lopez, CEO and president, AMC. "Our guests clearly choose to see movies in our IMAX auditoriums because the experience is unparalleled in terms of sight and sound, and it continues to be the premium offering in our portfolio of moviegoing options. -

Graeme Ferguson, One of the Founders of the Classmate, and Roman Kroiter to Invent a IMAX Corporation, Was Born in Toronto in 1929

Git&irsm FERGUSON Graeme Ferguson, one of the founders of the classmate, and Roman Kroiter to invent a IMAX Corporation, was born in Toronto in 1929. revolutionary new motion picture experience which Filmmaking When he was young he moved with his family to they named IMAX. Gait. Graeme attended Dickson Public School before For moving to Gait Collegiate in 1942. The son of Frank the next 23 years Mr. Ferguson served as president Ferguson, arguably the most popular teacher in the of IMAX Corporation. During this time the history of GCI, Graeme grew up in an atmosphere partners saw their dream realized as IMAX of ‘truth and discovery’. This carried into the school theatres proliferated around the world to more than 150 specialized 22 countries. with science teacher C. Gordon Clarke. According theatres in to Graeme, “any sort of experiment we wanted to do Currently Mr. Ferguson continues as a Gordon Clarke would encourage. He was always filmmaker, challenged to make new discoveries using up to supporting anything we were curious about.” the film medium. Among his JMM( films are North Not surprisingly, with his father’s political of Superior, The Dream is Alive, Blue Planet, Into the Deep, Destiny background as a the CCF candidate for South and in Space. Most recently, he produced L5: First Waterloo, Mr. Ferguson attended the University of City in Space, a large-forn-iat 3D film, and was honoured with NASA’s coveted Toronto where he graduated with a degree in Political Silver Snoopy Award for outstanding contribution to the Science and Economics. -

RECORD PACKET COPY CRUZ, CA 95060 27-4863 • W15a

~STATE OF CALIFORNIA- THE RESOURCES AGENCY CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION CENTRAL COAST DISTRICT OFFICE ONT STREET, SUITE 300 RECORD PACKET COPY CRUZ, CA 95060 27-4863 • W15a Filed: 12/02/99 49th day: 01/20/00 1 l80 h day: 05/30/00 Staff: SG Staff report: 12/15/99 Hearing date: 01112/00 COASTAL DEVELOPMENT PERMIT APPLICATION Application number ....... 3-99-076 Applicant.. ....................... Monterey Plaza Hotel LP IMAX Theater Project location ............... 270 and 284 Cannery Row, City of Monterey, Monterey County (APNs • 001-031-004 and 001-031-005) Project description ......... Demolish existing abandoned cannery, except for building front wall along Cannery Row, and construct a new building with three levels (two stories at and above grade and a lower level to accommodate bottom of theater screen), 48,070 square feet (total of all floors) to include a 500 seat large format theater, 1807 square feet of retail space, 2088 square feet of office space, and 2618 square feet of meeting space, with public coastal access. Approvals Received ....... City of Monterev: Permit Number 99-140, 10/05/99 File documents ................ City of Monterey Cannery Row certified Land Use Plan. Staff recommendation ... Approval with Conditions California Coastal Commission January 12, 2000 Meeting in Santa Monica • Staff: S. Guiney, Approved by: G:\Central Coast\STAFF REPORTS\3. CCC Meeling Packet\00101\3-99-0761MAX Theater stfrpt 12. 16.99.doc Application 3-99-076 Staff Report Monterey Plaza Hotel LP IMAX Theater Page 2 • Staff Report Contents I. Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Staff Recommendation on Coastal Development Permit .................................................................... 3 III. Conditions of Approval ......................................................................................................................