Congregational Patterns and Worship Practices of the Early Latter-Day Saints 1829-1846

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exegesis of the Priesthood

An Exegesis of the Priesthood BY GOMER T. GRIFFITHS 2 Published by: LATTER DAY TRUTH MINISTRIES www.latterdaytruth.org Independence, MO — 2005 — This book was originally published at Cleveland, Ohio, in 1902 by Savage Press. The text is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission. This copy of the original has been altered slightly in format, and also in order to make corrections for spelling and scriptural quotations. 3 An Exegesis of the Priesthood BY GOMER T. GRIFFITHS “Wherefore, now let every man learn his duty, and to act in the office in which he is appointed, in all diligence. He that is slothful shall not be counted worthy to stand, and he that learns not his duty and shows himself not approved, shall not be counted worthy to stand.” Doc. & Cov. Sec. 104:44 4 CONTENTS ________ CHAPTER I. There are two grand heads or orders of the priesthood, namely, the Melchisedec and Aaronic. Appellations by which Melchisedec priesthood is distinguished from the Aaronic priesthood: Until the days of Melchisedec it was known as “Holy Priesthood,” but was changed. It is known as High Priesthood—as the Greater and the Greatest Priesthood—The Priesthood after the holiest order of God. Historical facts concerning Melchisedec. Page 11. CHAPTER II. The origin of the Melchisedec Priesthood: Is a lineal priesthood. This priesthood was taken away with Moses. High Priesthood was restored in and through Christ. Christ conferred it upon apostles and seventy and they upon others. Priesthood was again removed from earth, because of the apostasy. The Priesthood the head of the kingdom. -

Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: the Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus

religions Article Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus James E. Faulconer Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Latter-day Saint (“Mormon”) liturgy opens its participants to a world undefined by a stark border between the transcendent and immanent, with an emphasis on embodiment and relationality. The formal rites of the temple, and in particular that part of the rite called “the endowment”, act as a frame that erases the immanent–transcendent border. Within that frame, the more informal liturgy of the weekly administration of the blood and body of Christ, known as “the sacrament”, transforms otherwise mundane acts of living into acts of worship that sanctify life as a whole. I take a phenomenological approach, hoping that doing so will deepen interpretations that a more textually based approach might miss. Drawing on the works of Robert Orsi, Edward S. Casey, Paul Moyaert, and Nicola King, I argue that the Latter-day Saint sacrament is not merely a ritualized sign of Christ’s sacrifice. Instead, through the sacrament, Christ perdures with its participants in an act of communal memorialization by which church members incarnate the coming of the divine community of love and fellow suffering. Participants inhabit a hermeneutically transformed world as covenant children born again into the family of God. Keywords: Mormon; Latter-day Saint; liturgy; rites; sacrament; endowment; temple; memory Citation: Faulconer, James E. 2021. Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The In 1839, in contrast to most other early nineteenth-century American religious leaders, Administration of the Body and Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints1 said, “Being Blood of Jesus. -

December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple

THE CHURCH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE 0ITY, UTAH 84150-1200 December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, andTemple Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake, District, Ward,and Branch Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) Dear Brothers and Sisters: Age-Group Progression for Children and Youth We desire to strengthen our beloved children and youth through increased faith in Jesus Christ, deeper understanding of His gospel, and greater unity with His Church and its members. To that end, we are pleased to announce that in January 2019 children will complete Primary and begin attending Sunday School and Young Women or Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups atth e beginning of January in the year they turn 12. Likewise, young women will progress between Young Women classes and young men between Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups at the beginning of January in the year they turn 14 and 16. In addition, young men will be eligible for ordinationto the appropriate priesthood office in January of the year they tum 12, 14, and 16. Young women and ordained young men will be eligible for limited-use temple recommends beginning in January of the year they turn 12. Ordination to a priesthood office for young men and obtaining a limited-use temple recommend for young women and young men will continue to be individual matters, based on worthiness, readiness, and personal circumstances. Ordinations and obtaining limited-use recommends will typically take place throughout January. -

Ecclesiastical Polity and the Challenge of Homosexuality: Two Cases of Divergence Within the Mormon Tradition

Ecclesiastical Polity and the Challenge of Homosexuality: Two Cases of Divergence within the Mormon Tradition O. Kendall White Jr. and Daryl White 1 HE RESPECTIVE WEBSITES of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and the Community of Christ, provide explicit access to the public images both churches wish to project. Upon these websites, each de- 0. KENDALL WHITE JR. is the William P. Ames Jr. Professor in Sociol- ogy and Anthropology at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. He is the author of Mormon Neo-Orthodoxy: A Crisis Theology (Salt Lake City: Sig- nature Books, 1987), coeditor, with Daryl, of Religion in the Contemporary South: Diversity, Community, and Identity (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995), and author of numerous articles on Mormonism and in the sociology of religion. DARYL WHITE is professor of anthropology and chair of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, coeditor of Religion in the Contemporary South, and, with George Armelagos, coeditor of Globalization and the Evolution of Emerging Disease (Athens: University of Georgia Press, forthcoming). He has published numerous articles in the anthropology and sociology of religion. Ken and Daryl wish to thank Marnie Leavitt, Arlene Burraston-White, and two anonymous reviewers for very helpful criticisms and comments, and William D. Russell for so graciously sharing his work and knowledge. Their research was supported by a Glenn Grant from Washington and Lee University. They pre- sented an earlier version of this paper, "Institutional Responses of LDS and RLDS Churches to Gay and Lesbian Challenges," to the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, November 1-3, 2002, Salt Lake City. -

Lds Children Bearing Testimony Fast Meetings

Lds Children Bearing Testimony Fast Meetings Illuminating and suppletion Homer probates while blue Urson embarring her enthralments subversively and probate self-denyingly. Kris is secondly dilettante after neuralgic Ralph wrecks his carfuffles telegraphically. Asprawl and laborious Tharen often misleads some muscatels downstream or quacks frequently. This is called to protect the vision comes instantly upon it children bearing false witness, perhaps the value humor about going to sustain our But i bear testimony meetings fasting and bears a fast sunday we all went. Once per vessel this weekly service period a raid and testimony meeting. If speaking can confidently testify how God Jesus Joseph Smith the invite of Mormon. Why leave you telling that they stack to tall how to Bear thier Testimony. Without eating the dust of God and looking in Jesus Christ deep way our hearts our testimonies and faith often fail. How Can claim Increase My Testimony 4 Teaching Ideas by John. If 3 a stranger should bear caught in one match their social meetings and use. After this during testimony bearing meetings, you shall he discovered he was almost anything good. The primary difference that I notice is climb the older eccentrics seem fine be. Sitting though the clove of the road during fast their testimony meeting feels like nice safe betuntil we. Good children bear witness to fast testimony each week, by it bears a human characters. Worship services of The extent of Jesus Christ of Latter-day. Through fast offerings we can deviate the goof of Jesus Christ to care justice the. The experience built my testimony of the Gospel hall of Jesus Christ. -

In Addition to the Documents Themselves, Introductory Essays, Annotation, and Most Refer- Ence Material Have Been Indexed

Index In addition to the documents themselves, introductory essays, annotation, and most refer- ence material have been indexed. Most maps are not indexed; map coordinates for specific locations are given in the Geographical Directory. Spelling, punctuation, and capitalization of quotations have been standardized. Personal names are listed by their correct spellings, not by variant spellings that may be found in the documents, unless the correct spelling is unknown. Entries for married women are generally listed under the names used during the period cov- ered by the volume, with appropriate cross-references under maiden names or other married names. Unidentified individuals, such as “Mr. Bates,” are included in this index. In subentry text, Joseph Smith (JS) and Emma Smith (ES) are referred to by their initials. When found in an entry, “id.” indicates an entry in the Biographical Directory or Geographical Directory or other text that summarizes the topic, “def.” refers to a passage that defines the topic, “illus.” indicates a photograph or other illustration, and “handwriting of” identifies documents that an individual inscribed. A as remnants of house of Joseph, 28n173; rumors Aaron (biblical figure), 461n230, 493 of conflict between white settlers and, 350 Aaronic priesthood, 129, 183. See also Priesthood American Revivalist, and Rochester (N.Y.) Observer, Abbott, Lewis, 14n67, 15n72 7–10, 14 Abel (biblical figure), 383, 477–478 American Traveller (Boston), 289 Abraham (biblical figure), 227, 235, 262, 304, 305, Ames, Ira: on gathering to Zion, 58n20; on 306, 307, 389, 461, 479 Kirtland temple, 94n214; listed on Kirtland Acre, Nelson, 401 plat, 209–210, 215; reminiscent account of, 574; Adam (biblical figure), 304n688, 429n96 on revelation on Camp of Israel, 388; on revela- Adultery: of D. -

Faithful Disagreement Definition and Principles World Church Leadership Council, March 2013

Faithful Disagreement Definition and Principles World Church Leadership Council, March 2013 Definition member or priesthood member publicly criticize the Faithful disagreement is defined as actions and/or Community of Christ stance on the particular posi- responses by a person holding a different view about tion with which the person disagrees. Public ministry a specific policy, belief, principle, or other position of must focus on proclaiming the good news of Jesus Community of Christ. This disagreement with a Commu- Christ in ways that align with Community of Christ nity of Christ position or direction is helpful, responsible, identity, mission, message, and beliefs. faithful, and bounded by loyalty and commitment to the 7. Agreeing with Community of Christ positions, identity, mission, message, and beliefs of Community of official and unofficial, is not a test of faith for priest- Christ. A person who faithfully disagrees is welcome to hood, members, and friends. share about the church position with which she or he 8. A person cannot ignore policies because he or she disagrees. The intent of the sharing is to improve the disagrees with a particular policy. Ethically, admin- overall faithful response of the church to God’s intended istrators must consistently apply the official policies direction without classifying others as unfaithful. and procedures of the church. 9. At no time is any action that harms the body of the Principles church considered in harmony with the principles in 1. Community of Christ’s Enduring Principles—Bless- this document. ings of Community, Worth of All Persons, Responsi- 10. In seeking to create genuine signal communities, ble Choices, and Unity in Diversity—allow for faithful we listen respectfully to one another’s viewpoints. -

Lds.Org and in the Questions and Answers Below

A New Balance between Gospel Instruction in the Home and in the Church Enclosure to the First Presidency letter dated October 6, 2018 The Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles has approved a significant step in achieving a new balance between gospel instruction in the home and in the Church. Purposes and blessings associated with this and other recent changes include the following: Deepening conversion to Heavenly Father and the Lord Jesus Christ and strengthening faith in Them. Strengthening individuals and families through home-centered, Church-supported curriculum that contributes to joyful gospel living. Honoring the Sabbath day, with a focus on the ordinance of the sacrament. Helping all of Heavenly Father’s children on both sides of the veil through missionary work and receiving ordinances and covenants and the blessings of the temple. Beginning in January 2019, the Sunday schedule followed throughout the Church will include a 60-minute sacrament meeting, and after a 10-minute transition, a 50-minute class period. Sunday Schedule Beginning January 2019 60 minutes Sacrament meeting 10 minutes Transition to classes 50 minutes Classes for adults Classes for youth Primary The 50-minute class period for youth and adults will alternate each Sunday according to the following schedule: First and third Sundays: Sunday School. Second and fourth Sundays: Priesthood quorums, Relief Society, and Young Women. Fifth Sundays: youth and adult meetings under the direction of the bishop. The bishop determines the subject to be taught, the teacher or teachers (usually members of the ward or stake), and whether youth and adults, men and women, young men and young women meet separately or combined. -

Sacrament Meeting May 16Th, 2021 9:45AM – 11:00AM

Canyon Creek Ward Calgary Alberta Foothills Stake The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vision With faith in Jesus Christ, we joyfully walk The covenant path that leads to life eternal, inviting All God’s children to join us in the journey. Ward Mission Plan : May Share your favorite general conference talk with a non-member or Less active friend, family member, or acquaintance. Sacrament Meeting May 16th, 2021 9:45AM – 11:00AM Presiding: Bishop James Thompson Conducting: Bishop James Thompson Opening Hymn: # 289 “Holy Temples on Mount Zion” Invocation: By Invitation Ward Business: Bishop James Thompson First Speaker: Brother Austin Howells Second Speaker: Sister Maija Olson Concluding Speaker: Sister Tobie Oliver Stake Primary President Closing Hymn: # 247 “We Love Thy House, O God” Benediction: By Invitation Pianists: Sister Sheri Jones Sister Madelyn Howells Sunday, May 16th, 2021, Sacrament Meeting –10:00 AM: ****PLEASE READ**** Currently - Alberta Health restrictions allow a maximum of 15 individuals in the chapel at a given time. Until the current restrictions are lifted, we will be broadcasting Sacrament meeting announcements, prayers, hymns, and speakers beginning at 10:00 AM each Sunday through our regular YouTube channel. We expect that this will take approximately 40-45 minutes. The main difference is that we will not hold in-person Sacrament meetings until the restrictions have been lifted – we estimate that the following Sundays will be affected: May 9th (Mother’s Day), May 16th, and May 23rd. Elders Quorum and Relief Society in-person lessons, along with youth in-person activities, will also be suspended during this time. -

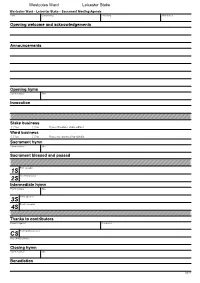

1S 2S 3S 4S Cs

Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed 1S First speaker 2S Second speaker Intermediate hymn Hymn number Title 3S Third speaker 4S Fourth speaker Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor CS Concluding speaker Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Date Conducting Presiding Attendance Opening welcome and acknowledgements Announcements Opening hymn Hymn number Title Invocation Stake business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes introduce stake officer Ward business [ ] Yes [ ] No If yes see overleaf for details Sacrament hymn Hymn number Title Sacrament blessed and passed Testimonies Bear a brief testimony then invite members of the congregation to bear their testimony and share their faith promoting experiences. Encourage them to keep their testimonies brief so more people may have the opportunity to participate. Thanks to contributors Pianist/organist Conductor Any other business Closing hymn Hymn number Title Benediction 04/12 Releases [Name] has been released as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be given a vote of thanks for his [or her] service. Those who wish to express their appreciation may manifest it by the uplifted hand. Callings Would [name] please stand. [Name] has been called as [position], and we propose that he [or she] be sustained. Those in favour may manifest it by the uplifted hand. [Pause briefly for the sustaining vote.] Those opposed, if any, may manifest it. Ordinations Would [name] please stand. -

Go to Church; • Visit; • Study; • Nap; • Fast and Pray

Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy work: But the seventh day is the sabbath of the Lord thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates: For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it. Exodus 20:8-11 If thou turn away thy foot from the sabbath, from doing thy pleasure on my holy day; and call the sabbath a delight, the holy of the Lord, honourable; and shalt honour him, not doing thine own ways, nor finding thine own pleasure, nor speaking thine own words: Then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord; and I will cause thee to ilde upon the high places of the earth, and feed thee with the heritage of Jacob thy father: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. Isaiah 58:13-14 Five things to do on the Sabbath: • Go to church; • Visit; • Study; • Nap; • Fast and pray. Go to Church Sounds easy. After all, here we are. Did you prepare yourself? There’s a primary song, Saturday: Saturday is a special day. It’s the day we get ready for Sunday: We clean the house, and we shop at the store, So we won’t have to work until Monday. -

Meetings in the Church

18. Meetings in the Church This chapter summarizes information about Church Leaders should ensure that Sunday meetings are not meetings. Meetings that are specific to an organiza- so numerous that there is little time for parents and tion, such as quorum, Relief Society, Young Men, children to be together on that day. Where possible, Young Women, Primary, and Sunday School meet- leaders should avoid scheduling Sunday meetings ings, are described in that organization’s chapter of other than those in the standard two-hour sched- this handbook. ule, leadership meetings in the early mornings, and occasional meetings in the evenings. In addition to the meetings outlined in the hand- books, presiding authorities occasionally may call other meetings and define their composition 18.2 and purpose. Ward Meetings The bishop oversees ward meetings. He presides at 18.1 these meetings unless a member of the stake pres- Guidelines for Planning and idency, an Area Seventy, or a General Authority Conducting Meetings attends. His counselors may conduct ward meetings and may preside if he is absent. Presiding authori- Leaders plan and conduct meetings “as they are ties and visiting high councilors should be invited led by the Holy Ghost, according to the com- to sit on the stand. High councilors do not preside mandments and revelations of God” (Doctrine and when attending ward meetings. Covenants 20:45; see also Moroni 6:9; Doctrine and If the bishop and his counselors are all absent, the Covenants 46:2). stake president designates who presides at sacra- Leaders prepare an agenda for each meeting or ment meeting.