Constitutional Moments, Precommitment, and Fundamental Reform: the Case of Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICROOMNIBUS CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. DE T.C.E.I. Línea N° 59 Servicios Comunes Básicos Servicios Expresos

MICROOMNIBUS CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES S.A. DE T.C.E.I. Línea N° 59 Servicios Comunes Básicos Recorrido A (por ESTACIÓN LA LUCILA) ESTACIÓN BUENOS AIRES (LÍNEA BELGRANO SUR - CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUENOS AIRES) - INTENDENTE CORONEL AMARO ÁVALOS y DOMINGO DE ACASSUSO (PARTIDO DE VICENTE LÓPEZ - PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES) Recorrido B (por BARRIO GOLF) ESTACIÓN BUENOS AIRES (LÍNEA BELGRANO SUR - CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUENOS AIRES) - INTENDENTE CORONEL AMARO ÁVALOS y DOMINGO DE ACASSUSO (PARTIDO DE VICENTE LÓPEZ - PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES) Recorrido C ESTACIÓN BUENOS AIRES (LÍNEA BELGRANO SUR - CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUENOS AIRES) – ESTACIÓN DE TRANSFERENCIA DE TRANSPORTE PÚBLICO DE PASAJEROS DE CORTA Y MEDIA DISTANCIA DE VICENTE LÓPEZ (PARTIDO DE VICENTE LÓPEZ - PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES) Servicios Expresos Recorrido D (por AUTOPISTA PRESIDENTE ARTURO UMBERTO ILLIA) - sobre la traza del Recorrido B ESTACIÓN BUENOS AIRES (LÍNEA BELGRANO SUR - CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUENOS AIRES) - INTENDENTE CORONEL AMARO ÁVALOS y DOMINGO DE ACASSUSO (PARTIDO DE VICENTE LÓPEZ - PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES) Los Servicios Expresos del Recorrido D se prestarán a título experimental, precario y provisorio “Ad referéndum” de lo que disponga la SECRETARÍA DE GESTIÓN DE TRANSPORTE. 1 Itinerario entre Cabeceras Recorrido A IDA A VICENTE LÓPEZ: Desde ESTACIÓN BUENOS AIRES por OLAVARRÍA, AVENIDA VÉLEZ SÁRSFIELD, AVENIDA AMANCIO ALCORTA, AVENIDA DOCTOR RAMÓN CARRILLO, DOCTOR ENRIQUE FINOCHIETTO, SALTA, AVENIDA BRASIL, BERNARDO DE IRIGOYEN, carril del Corredor METROBÚS 9 DE JULIO circulando -

Límite De La Cuenca Del Río Matanzariachuelo

ANEXO II “INFORME DE DELIMITACIÓN TOPOGRÁFICA DE LA CUENCA HIDROGRÁFICA DEL RÍO MATANZA-RIACHUELO” El presente informe contiene los límites topográficos, definidos siguiendo las curvas de nivel, de la cuenca y de las subcuencas que conforman la cuenca hidrográfica del Río Matanza-Riachuelo (CMR). Los mismos se trazaron sobre la base de las cartas topográficas del Instituto Geográfico Militar (IGM) a escala 1:50.000 denominadas: Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 3557-7-3; Lanús, 3557-13-1; Empalme San Vicente, 3557-13-3; Campo de Mayo, 3560-12-4; Lozano, 3560-17-4; Marcos Paz, 3560-18-1; Aeropuerto Ezeiza, 3560-18-2; General Las Heras, 3560-18-3; Ezeiza, 3560-18-4; Cañuelas, 3560-24-1 y Estancia La Cabaña, 3560-24-2; correspondientes a relevamientos efectuados en el período comprendido entre los años 1907-1962. Dadas las características socioeconómicas del área y a los fines del saneamiento de la cuenca Matanza-Riachuelo, se determinó apropiado considerar a las subcuencas de los Arroyos de la Cañada Pantanosa y Barreiro separadas de la subcuenca del Arroyo Morales a la cual pertenecen y, a las cuencas de los Arroyos Finocchieto, Dupy, Susana y Don Mario como una sola subcuenca. Los mapas correspondientes a límites de la cuenca y subcuencas se adjuntan en las figuras 1 y 2. 1 CUENCA HIDROGRÁFICA DEL RÍO MATANZA-RIACHUELO (LÍMITE POR CALLES) El límite por calles de la CMR se estableció considerando el límite hidrográfico de la cuenca. Para el trazado se utilizaron: 1) Los archivos digitales callejeros, trazado de ejes medios de calzada, de los partidos integrantes de la cuenca. -

Mensaje De Asunción Del Presidente D. Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín 10 De Diciembre De 1983

Año VI – Nº 153 – Mayo 2018 Mensaje de asunción del Presidente D. Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín 10 de Diciembre de 1983 ISSN 2314-3215 Año VI – Nº 153- Mayo 2018 Dirección Servicios Legislativos Subdirección Documentación e Información Argentina Departamento Referencia Argentina y Atención al Usuario Mensajes presidenciales Mensaje de asunción Congreso de la Nación Argentina Acta del 10 de diciembre de 1983 Presidente de la República Argentina Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín (1983‐1989) Dirección Servicios Legislativos Subdirección Documentación e Información Argentina Departamento Referencia Argentina y Atención al Usuario PROPIETARIO Biblioteca del Congreso de la Nación DIRECTOR RESPONSABLE Alejandro Lorenzo César Santa © Biblioteca del Congreso de la Nación Alsina 1835, 4º piso. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, mayo 2018 Queda hecho el depósito que previene la ley 11.723 ISSN 2314-3215 “Mensaje de asunción del Presidente D. Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín 10 de Diciembre de 1983” Departamento Referencia Argentina y Atención al Usuario PRESENTACIÓN En este número de la publicación Dossier legislativo: Mensajes presidenciales se reproduce el discurso de D. Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín, Presidente de la República Argentina, ante la Asamblea Legislativa del 10 de diciembre de 1983. Cabe señalar que los Mensajes Presidenciales han sido extraídos de la colección de Diarios de Sesiones de ambas Cámaras del Honorable Congreso de la Nación, disponible en esta Dirección. “Las Islas Malvinas, Georgias del Sur y Sandwich del Sur son argentinas” 2 “Mensaje de asunción del Presidente D. Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín 10 de Diciembre de 1983” Departamento Referencia Argentina y Atención al Usuario Dossier legislativo Año l (2013) N° 001 al 006 Mensajes presidenciales. -

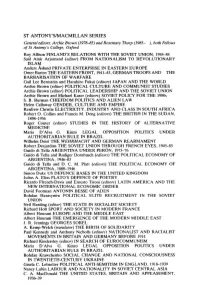

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

Catalogo De Las Colecciones Medallisticas De La ANH (Tomo 2

ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE LA HISTORIA CATALOGO DE LAS COLECCIONES MEDALLISTICAS DE LA ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE LA HISTORIA Tomo II - Fascículo 1 Advertencia del Académico de Número Dr. LUIS SANTIAGO SANZ Compilación de la Lic. DORA BEATRIZ PINOLA BUENOS AIRES 1990 I.S.B.N. 950-9846:14 8 CATALOGO DE LAS COLECCIONES MEDALLISTICAS DE LA ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE LA HISTORIA Tomo II - Fascículo 1 EDICION DE HOMENAJE AL QUINTO CENTENARIO DEL DESCUBRIMIENTO DE AMERICA ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE LA HISTORIA CATALOGO DE LAS COLECCIONES MEDALLISTICAS DE LA ACADEMIA NACIONAL DE LA HISTORIA Tomo II - Fascículo 1 Advertencia del Académico de Número Dr. LUIS SANTIAGO SANZ Compilación de la Lie. DORA BEATRIZ PINOLA BUENOS AIRES 1 990 COMISION DE NUMISMATICA Y MEDALLISTICA Director: Dr. Luis Santiago Sanz Vocales: Clmte. Laurio H. Destéfani Dr. Carlos A. Luque Colombres © 1990. Academia Nacional de la Historia Printed in Argentine. Impreso en la Argentina Queda hecho el depósito que indica la ley 11.723 ADVERTENCIA Con posterioridad a la publicación del Catálogo de las Colec ciones Medallísticas de la Academia Nacional de la Historia, editado en 1987, se agregaron al Gabinete de Medallas de la Institución más de dos centenares de piezas que han enriquecido el acervo histórico que conserva la Academia. El número y la importancia de los ejemplares incorporados, ha inducido a la Comisión a publicar un fascículo que —con los que se editen en lo sucesivo— servirá para integrar un segundo volumen que complementará el catálogo de medallas que posee la Academia. El ordenamiento que se adopta en el fascículo, sigue el sis tema, establecido para la clasificación de las medallas, expuesto en la introducción del referido catálogo. -

Nombre Direccion Ciudad

NOMBRE DIRECCION CIUDAD 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001MUFLUVIALSUD AV PEDRO DE MENDOZA 330 CABA 013COLOADUANADECOLON PEYRET 114 COLON 013MUCOLON PEYRET 114 COLON 018 CARREFOUR ROSARIO CIRC E PRESBIRERO Y CENTR ROSARIO 018 CARREFOUR ROSARIO CIRVUNVALACION Y ALBERTI ROSARIO 02 ALFA MIGUEL CANE 4575 QUILMES 022 CARREFOUR MAR DEL PLA CONSTITUCION Y RUTA 2 MAR DEL PLATA 073MUEZEIZA AU RICCHIERI KM 33 500 SN EZEIZA 12 DE OCTUBRE AV ANDRES BARANDA 1746 QUILMES 135 MARKET LA RIOJA 25 DE MAYO 151 LA RIOJA 135 MARKET LA RIOJA 25 DE MAYO 151 LA RIOJA 1558 SOLUCIONES TECNOLOGI AV ROCA 1558 GRAL ROCA 166LA MATANZA SUR CIRCUNV 2 SECCION GTA SEC CIUDAD EVITA 167 MARKET JUJUY 1 BALCARCE 408 SAN SALVADOR DE JUJUY 18 DE MAYO SRL 25 DE MAYO 660 GRAL ROCA 18 DE MAYO SRL 25 DE MAYO 660 GRAL ROCA 180 CARREFOUR R GRANDE II PERU 76 RIO GRANDE 187 EXP ESCOBAR GELVEZ 530 ESCOBAR 206 MARKET BERUTI BERUTI 2951 CABA 2108 PLAZA OESTE PARKING J M DE ROSAS 658 MORON 2108 PLAZA OESTE PARKING J M DE ROSAS 658 MORON 219 CARREFOUR CABALLITO DONATO ALVAREZ 1351 CABA 21948421 URQUIZA 762 SALTA 21956545 PJE ESCUADRON DE LOS GAU SALTA 21961143 MITRE 399 SALTA 21965217 HIPOLITO YRIGOYEN 737 SALTA 21968433 URQUIZA 867 SALTA 220 ELECTRICIDAD ENTRE RIOS 397 ESQ BELGR TICINO 22111744 ESPANA 1033 SALTA 22113310 LEGUIZAMON 470 SALTA 22116355 CALLE DE LOS RIOS 0 SALTA 22129878 SAN MARTIN 420 JESUS MARIA 22135806 LORENZO BARCALA 672 CORDOBA 22135940 AV RICHIERI -

Presidentes Argentinos

Presidentes argentinos Período P O D E R E J E C U T I V O Presidente: BERNARDINO RIVADAVIA 1826-1827 Sin vicepresidente Presidente: JUSTO JOSÉ DE URQUIZA 1654-1860 Vicepresidente: SALVADOR MARÍA DEL CARRIL Presidente: SANTIAGO DERQUI Vicepresidente: JUAN ESTEBAN PEDERNERA 1860-1862 Derqui renunció y Pedernera, en ejercicio de la presidencia, declaró disuelto al gobierno nacional. Presidente: BARTOLOMÉ MITRE 1862-1868 Vicepresidente: MARCOS PAZ Presidente: DOMINGO FAUSTINO SARMIENTO 1868-1874 Vicepresidente: ADOLFO ALSINA Presidente: NICOLÁS AVELLANEDA 1874-1880 Vicepresidente: MARIANO AGOSTA Presidente: JULIO ARGENTINO ROCA 1880-1886 Vicepresidente: FRANCISCO MADERO Presidente: MIGUEL JUÁREZ CELMAN Vicepresidente: CARLOS PELLEGRINI 1886-1892 En 1890, Juárez Celman debió renunciar como consecuencia de la Revolución del '90. Pellegrini asumió la presidencia hasta completar el período. Presidente: LUIS SAENZ PEÑA Vicepresidente: JOSÉ EVARISTO URIBURU 1892-1898 En 1895, Luis Sáenz Peña renunció, asumiendo la presidencia URIBURU hasta culminar el período. Presidente: JULIO ARGENTINO ROCA 1898-1904 Vicepresidente: NORBERTO QUIRNO COSTA Presidente: MANUEL QUINTANA Vicepresidente: JOSÉ FIGUEROA ALCORTA 1904-1910 En 1906, Manuel Quintana falleció, por lo que debió terminar el período Figueroa Alcorta. Presidente: ROQUE SAENZ PEÑA 1910-1916 Vicepresidente: VICTORINO DE LA PLAZA En 1914, fallece Sáenz Peña, y completa el período Victorino de la Plaza Presidente: HIPÓLITO YRIGOYEN 1916-1922 Vicepresidente: PELAGIO LUNA Presidente: MARCELO TORCUATO DE ALVEAR 1922-1928 Vicepresidente: ELPIDIO GONZÁLEZ Presidente: HIPÓLITO YRIGOYEN 1928-1930 Vicepresidente: ENRIQUE MARTÍNEZ P O R T A L U N O A R G E N T I N A El 6 de setiembre de 1930 se produce el primer golpe de Estado en este período constitucional en la Argentina, por el cual se derroca a Yrigoyen. -

Senado De La Nación Argentina

SENADO DE LA NACIÓN Secretaria Parlamentaria PLENARIO DE LABOR PARLAMENTARIA REUNIÓN DE PRESIDENTES DE BLOQUE DEL 25 / 11 / 08 Firma de los Asistentes TEMARIO CONCERTADO SESIÓN DEL 26 / 11 / 08 HORARIOS: Comienzo ....15:00 hs.... (....14:30 hs.. timbre) Carácter de la sesión -- Secreta 9 Pública 9 Ej. de Acuerdos -- Juicio Político Asuntos Entrados: SI 1. HOMENAJES: 2. ORDENES DEL DÍA IMPRESOS A CONSIDERAR: ANEXO I, 655, 1205, 1075, 76, 1113, 903, 1111, 881, 1050, 1159, 1004, 525, 882, 1156, 1011, 119, 125, 126, 189, 262, 616, 888, 1157. 3. PREFERENCIAS A TRATAR VOTADAS CON ANTERIORIDAD: 4. ASUNTOS SOBRE TABLAS: Acordados: CD-69/08 DICTAMEN EN EL PROYECTO DE LEY EN REVISIÓN PRORROGANDO HASTA EL 30 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2009 INCLUSIVE, LA VIGENCIA DEL GRAVAMEN ESTABLECIDO POR LA LEY 25063, TÍTULO V, DE IMPUESTO A LA GANANCIA MÍNIMA PRESUNTA Y SUS MODIFICACIONES. CD-148/07 DICTAMEN EN EL PROYECTO DE LEY EN REVISIÓN TRANSFIRIENDO A TÍTULO GRATUITO UN INMUEBLE PROPIEDAD DEL ESTADO NACIONAL A LA MUNICIPALIDAD DEL DPTO. CAPITAL DE LA RIOJA, CON DESTINO AL FUNCIONAMIENTO DE LA ENTIDAD ASOCIACIÓN CIVIL “ATLÉTICO RACING CLUB”. S-166/07 Y S-49/08 DICTAMEN EN LOS PROYECTOS DE LEY CREANDO EN EL ÁMBITO DE SUBSECRETARIA DE DEFENSA DEL CONSUMIDOR EL REGISTRO NACIONAL “NO LLAME”. A solicitar: S-4012/08, S4189/08 PROYECTOS DE DECLARACIÓN ADHIRIENDO A LA CONMEMORACIÓN POR S-3952/08 EL DÍA INTERNACIONAL POR LA NO VIOLENCIA CONTRA LA MUJER, EL 25 DE NOVIEMBRE. (Texto Unificado). S-3707/08 PROYECTO DE DECLARACIÓN DECLARANDO DE INTERÉS EDUCATIVO LA TERCERA CAMPAÑA DE INFORMACIÓN Y CONCIENTIZACIÓN SOBRE LA PRESENCIA DE ARSÉNICO EN EL AGUA DE CONSUMO. -

Revive the Industrialization of Argentina's Patagonia!

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 27, Number 47, December 1, 2000 EIRNational Economy Revive the Industrialization of Argentina’s Patagonia! by Gonzalo Huertas and Cynthia Rush EIRhas repeatedly documented the dangerous state of disinte- nationalist Col. Enrique Mosconi, shut down operations in gration in which Argentina finds itself today, as a result of the key locations in the Patagonia, leaving unemployment and International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) free market policies, misery, and in some cases, ghost towns in its wake. A victim applied so brutally over the past decade, and continuing under of the vicious demilitarization policy imposed from Project the Fernando de la Ru´a administration which took office in Democracy headquarters in Washington, the Armed Forces December 1999. have been forced to withdraw from the strategically important In the early 1960s, Argentina’s economic development Argentine-Chilean border region. These are the conditions was, in many respects, comparable to that of Japan, as EIR which encourage Osvaldo Bayer, an Argentine mouthpiece documented in its 1983 book Industrial Argentina: Axis of for Fidel Castro’s Sa˜o Paulo Forum, to call for separating Ibero-American Integration. With its vanguard nuclear en- the Patagonia off and creating an “independent,” resource- ergy program and a developing capital goods and machine- rich “republic.” tool capability, it had the potential for rapidly becoming an Against the backdrop of today’s misery, the project pro- economic and industrial powerhouse. Had Argentina become posed in the early 20th Century by Argentine Public Works industrialized, this would have had a profound and positive Minister Ezequiel Ramos-Mex´ıa, to industrialize northern impact on Ibero-America’s international strategic position. -

Proyecto De Declaracin

Senado de la Nación Secretaria Parlamentaria Dirección General de Publicaciones (S-2415/10) PROYECTO DE DECLARACIÓN El Senado de la Nación, DECLARA: Su adhesión a la conmemoración del fallecimiento del ex presidente y jurisconsulto Roque Sáenz Peña, ocurrido el 9 de agosto de 1914, a 100 años de cumplirse la sanción de la ley de voto universal, secreto y obligatorio, conocida como la ley Sáenz Peña. Daniel R. Pérsico. – FUNDAMENTOS Señor Presidente: Roque Sáenz Peña nació en Buenos Aires el 19 de marzo de 1851. Hijo del doctor Luis Sáenz Peña y doña Cipriana Lahitte. Egresado del Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, ingresó a la Facultad de derecho donde comenzó su militancia política en el Partido Autonomista, dirigido por Adolfo Alsina. Sus estudios se vieron interrumpidos cuando se alistó como capitán de guardias nacionales durante la rebelión de Bartolomé Mitre contra el presidente electo Nicolás Avellaneda. Al finalizar el conflicto con el triunfo de las fuerzas leales en las que militaba, Roque fue ascendido a Comandante y continuó sus estudios hasta graduarse como doctor en leyes en 1875 con la tesis Condición jurídica de los expósitos. En 1876 fue electo diputado a la legislatura bonaerense por el Partido Autonomista Nacional. A pesar de sus cortos 26 años, sus condiciones políticas le valieron la elección de presidente de la Cámara por dos períodos consecutivos. En 1879, a poco de estallar la Guerra del Pacífico que enfrentó a Chile con Bolivia y Perú, Sáenz Peña, haciendo gala de su espíritu romántico de luchar por causas justas, se alistó como voluntario del ejército peruano en el que tendrá una destacada actuación. -

African Cowboys on the Argentine Pampas: Their Disappearance from the Historical Record Andrew Sluyter Louisiana State University, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons Faculty Publications Department of Geography & Anthropology 2015 African Cowboys on the Argentine Pampas: Their Disappearance from the Historical Record Andrew Sluyter Louisiana State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/geoanth_pubs Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Sluyter, African Cowboys on the Argentine Pampas: Their Disappearance from the Historical Record, BlackPast.org, 2015 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Geography & Anthropology at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. African Cowboys on the Argentine Pampas: Their Disappearance from the Historical Record Following the introduction of cattle into the Caribbean in 1493, during Christopher Columbus’s second voyage, cattle ranching proliferated in a series of frontiers across the grasslands of the Americas. While historians have recognized that Africans and their descendants were involved in the establishment of those ranching frontiers, the emphasis has been on their labor rather than their creative participation. In part that bias occurred because historians have traditionally relied on archival documents created by racially biased whites who emphasized their own roles rather than black ideas and creativity. In a recent book—Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500-1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012)—I addressed that issue by drawing on a range of complementary evidence such as landscape vestiges, oral histories, and material culture. -

European Immigration in Argentina from 1880 to 1914 Sabrina Benitez Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2004 European Immigration in Argentina from 1880 to 1914 Sabrina Benitez Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Latin American History Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Benitez, Sabrina, "European Immigration in Argentina from 1880 to 1914" (2004). Honors Theses. 22. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/22 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. European Immigration in Argentina from 1880 to 1914 Sabrina Benitez Ouachita Baptist University Senior Honors Thesis \.VI cu ll01 e. Situated in the southernmost region of South America, encompassing a variety of climates from the frigid Antarctic to the warmest tropical jungles, lies a country that was once a land of hope for many Europeans: Argentina. Currently Argentina is a country of one million square miles-four times larger than Texas, five times larger than France, with more than thirty seven million inhabitants. One third of the people in Argentina live in Greater Buenos Aires, the economic, political, and cultural center. Traditionally having an economy based on the exportation of beef, hides, wool, and corn, Argentina transformed this pattern during the country's boom years -the last decades of nineteenth century- toward industrialization and openness to a European model of progress and prosperity.