The Wonder Years: Televised Nostalgia Daniel Marcus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Word Farm 2016 Program

Word Farm 2016 Students Aubrie Amstutz Phalguni Laishram Joe Arciniega Gustavo Melo December Brown Claudia Niles Charlotte Burns Mia Roncati Derek Buss Melvin Singh Isabelle Carasso Corine Toren Christopher Connor Mel Weisberger Brendan Dassey Sydney Wiklund Phoebe DeLeon Dwight Yao Phi Do Julia Dumas Sylvia Garcia Gustavo A. Gonzalez Christine Hwynh Jae Hwan Kim Class Schedule Friday, January 29 9:00 Coffee & Snacks Sign-In 10:00-12:00 Session 1 Bryce & Jackie Zabel Tom Lazarus 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 2 David Gerrold Mitchell Kreigman Saturday, January 24 9:00 Coffee & Snacks 10:00-12:00 Session 3 Cheri Steinkellner J Kahn 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 4 Matt Allen & Lisa Mathis Dean Pitchford 3:00-3:30 Snacks 3:30-5:30 Session 5 Anne Cofell Saunders Toni Graphia 6:30 Dinner Annenberg Conference Room - 4315 SSMS Sunday, January 25 9:00 Coffee & Snacks 10:00-12:00 Session 6 Glenn Leopold Kevin McKiernan 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-3:00 Session 7 Amy Pocha Allison Anders 3:00-3:30 Snacks 3:30-5:00 Session 8 Omar Najam & Mia Resella Word Farm Bios Allison Anders Allison Anders is an award-winning film and television writer and director. She attended UCLA film school and in 1984 had her first professional break working for her film mentor Wim Wenders on his movie Paris, Texas (1984). After graduation, Anders had her first film debut,Border Radio (1987), which she co-wrote and co-directed with Kurt Voss. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Bailey, Dennis Resume

Dennis Bailey Height: 6’ Weight: 185 lbs Eyes: Brown Hair: Salt and Pepper Film Ocean’s 13 Supporting WB, Steven Soderbergh The Trip Supporting Artesian, Miles Swain Ways of the Flesh Supporting Columbia, Dennis Cooper Man of the Year Supporting Working Title, Dirk Shafer Television Good Christian Belles (Pilot) Co-star ABC-TV, Alan Poul Chase Co-star NBC, Dermott Brown The Simpsons Guest Star FOX, David Mirkin The Bernie Mac Show Guest Star FOX, Lee Shallat Chemel General Hospital Recurring ABC, Gloria Monty Melrose Place Guest Star FOX Crossing Jordan Guest Star NBC, Dick Lowry The Drew Carey Show Guest Star ABC, Brian Roberts Days of Our Lives Recurring NBC Sabrina, The Teenage Witch Recurring ABC, Melissa Joan Hart Martin Guest Star FOX, Garren Keith Dave’s World Guest Star CBS LA Law Guest Star NBC, Eric Laneuville Murder, She Wrote Guest Star CBS Columbo Guest Star NBC, Darryl Duke Dallas Recurring CBS, Leonard Pressman China Beach Recurring ABC, Mimi Leder Ally McBeal Recurring FOX, Kenny Ortega Television- MOW Search and Rescue (Pilot) Guest Star NBC, Robert Conrad Sworn to Vengeance Guest Star CBS, Peter Hunt Last Voyage of the Morrow Castle Guest Star HBO Theatre- Broadway Gemini Francis Geminiani Helen Hayes Leader of the Pack Gus Sharkey Ambassador Marriage of Figaro Figaro Circle in the Square Theatre- Off-Broadway Preppies Bogsy Promenade Professionally Speaking Teacher St. Peter’s Wonderland Alan Hudson Guild Theatre- Regional Dead White Males Principal Pettlogg Sustainable Theatre The Immigrant The Immigrant Actor’s Theatre, Louisville Are We There Yet? The Suitor Williamstown Merry Wives of Windsor Abraham Slender The Old Globe Blue Window Griever Atlanta Alliance Commercial List available upon request . -

Conversation with Writer, Producer, and Princeton Alumnus John Sacret

November 2, 2017 Conversation with writer, producer, and Princeton alumnus John Sacret Young Award-winning television producer behind such shows as China Beach, The West Wing and Police Story discusses his new book, Pieces of Glass – An Artoir Photo caption: Award-winning writer, producer, and Princeton alumnus John Sacret Young ’69 Photo credit: Courtesy of John Sacret Young Who: Award-winning writer, producer, and Princeton alumnus John Sacret Young What: John Sacret Young and Pieces of Glass – An Artoir, a visual presentation and conversation with Princeton Professor of Visual Arts Joe Scanlan focusing on Young’s latest memoir presented by the Lewis Center for the Arts in partnership with Princeton Garden Theatre and Labyrinth Books When: Monday, November 13 at 6:30 p.m. Where: Princeton Garden Theatre, 160 Nassau St., Princeton Free and open to the public but ticketed; advance reservations are encouraged at https://sacretyoung.eventbrite.com Event information: http://arts.princeton.edu/events/john-sacret-young-pieces- glass-artoir/ (Princeton, NJ) The Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton University, in partnership with Princeton Garden Theatre and Labyrinth Books, will present “John Sacret Young and Pieces of Glass –An Artoir,” a visual presentation and conversation with Princeton Professor of Visual Arts Joe Scanlan focusing on Young’s latest memoir, presented by the Lewis Center for the Arts in partnership with Princeton Garden Theatre and Labyrinth Books. The event will take place on Monday, November 13 at 6:30 p.m. at Princeton Garden Theatre, 160 Nassau Street in Princeton. The event is free and open to the public but ticketed; advance reservations are encouraged at https://sacretyoung.eventbrite.com. -

Award Winner Kristin Chenoweth (You're a Good Man

THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF HALLMARK CHANNEL’S ‘COUNTDOWN TO CHRISTMAS’ AND HALLMARK MOVIES & MYSTERIES’ ‘MIRACLES OF CHRISTMAS’ WILL BE THE BEST CHRISTMAS EVER Original Movie Premieres Every Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday Night BEVERLY HILLS, CA – July 26, 2019 – This holiday, original movie premieres will be on Thursday and Friday on Hallmark Movies & Mysteries’ “Miracles of Christmas” and Saturday and Sunday during Hallmark Channel’s 10th anniversary of “Countdown to Christmas.” Across the networks there will be 40 original movie premieres. On Hallmark Channel, Tony® and Emmy® Award winner Kristin Chenoweth (You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, “Pushing Daisies”) and Scott Wolf (“Party of Five”) star in the Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation of “A Christmas Love Story”; Lacey Chabert (Mean Girls) and Sam Page (“The Bold Type”) find romance in the City of Lights in “Christmas in Rome”; while Candace Cameron Bure (“Fuller House”) and Tim Rozon (“Schitt’s Creek”) find themselves in “Christmas Town.” On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, Nikki Deloach (“Awkward”) and Michael Rady (“Timeless”) team up again for “Two Turtle Doves”; Marc Blucas (“The Fix”), Melissa Claire Egan (“The Young and the Restless”) and Patti Murin (Frozen, “Chicago Med”) star in “Holiday for Heroes”; and Grammy Award winner Amy Grant stars in the all-new movie, “When I Think of Christmas.” The announcement was made today as part of Crown Media Family Networks’ bi-annual Television Critics Summer Press Tour. “Each year our holiday movie slates get bigger, the movies get better, and the ratings grow stronger and I have no doubt that this will prove to be the most successful season yet,” said Michelle Vicary, EVP, Programming & Network Publicity. -

Nurses of the Vietnam War Marginalized Protagonists and Narrative Authority by Brie Winnega a Thesis Presented for the B. A. D

Nurses of the Vietnam War Marginalized Protagonists and Narrative Authority by Brie Winnega A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2017 © 2017 Brie Winnega Acknowledgements Three faculty members in particular deserve recognition for their sustained support over the duration of this project. First I must acknowledge my adviser Julian Levinson, who encouraged my interest in Vietnam nurse memoirs upon first meeting me and whose enthusiasm from the very beginning made all the difference. His feedback was instrumental to the evolution and final shape of my argument, and I am grateful for our conversations which opened my mind to new possibilities and ways of reading. Professor Adela Pinch provided similar feedback, especially during the research phase of my project. Her guidance helped me develop my skills researching larger-scale projects. Furthermore, Adela’s flexibility and enthusiastic leadership made our fall cohort a comfortable and productive space. She has been a consistent source of encouragement and advice, offering support to all her students that often seemed to exceed the call of duty. In addition, Professor Gillian White was often my source for the practical, detail-oriented feedback necessary for this type of project. I am especially grateful for her unparalleled strategizing during critical junctures of the thesis process. Finally, my utmost gratitude goes to the Vietnam nurses for allowing me to read and learn from their stories. Thank you for enriching our understanding of the war with reports of your experiences, especially when the world failed to acknowledge you. Abstract Because they are not soldiers, politicians, and usually not males, Army nurses have not figured prominently in major Vietnam discourses. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

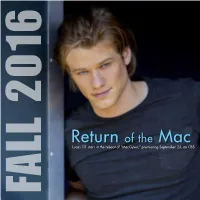

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

This Is a Test

‘ROCK THE HOUSE’ CAST BIOS JACK COLEMAN (Max) – Jack Coleman stars in NBC’s Emmy-nominated ensemble drama series “Heroes” as the mysterious Noah Bennett. Seemingly an unassuming family man as father to Claire, played by Hayden Panettiere, Bennett is also a man of mystery who has an interest in people with special abilities. Coleman has performed on Broadway, off-Broadway, in film and on television. Series roles include “Dynasty,” “Nightmare Café,” “Oh Baby” and “Steven King’s Kingdom Hospital.” Recently, he has been featured on such programs as “Entourage,” “Nip/Tuck,” “Without a Trace” and “CSI Miami.” On stage, Coleman starred on Broadway in Bill Cain’s Stand-Up Tragedy in a part he originated at the Mark Taper Forum. He was nominated for a Los Angeles Drama Critics’ Circle Award for his performance. He reprised the role in San Francisco at the Marines Memorial Theater and in Connecticut at The Hartford Stage Company before opening in New York. Coleman won a Los Angeles Drama Critics’ Circle Award for his performance in John Godber’s Bouncers at the Tiffany Theater and also starred off-Broadway in Simon Gray’s The Common Pursuit. Coleman has also appeared in regional theaters across the country, playing Danny Zuko in Grease from Long Island, New York to Odessa, Texas (where his character in “Heroes” resides), and performing Othello and Loves’ Labours Lost at the Globe of the Great Southwest. Coleman wrote, produced and starred in a short film entitled “Studio City,” an audience favorite at such film festivals as the Los Angeles International Short Film Festival and the New Orleans Media Experience. -

An Examination of Disability Stereotypes in Medical Dramas

AN EXAMINATION OF DISABILITY STEREOTYPES IN MEDICAL DRAMAS BEFORE AND AFTER THE PASSAGE OF THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT (ADA) Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Communications By Allison Marie Lewis UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, OH August 2014 AN EXAMINATION OF DISABILITY STEREOTYPES IN MEDICAL DRAMAS BEFORE AND AFTER THE PASSAGE OF THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT (ADA) Name: Lewis, Allison Marie APPROVED BY: __________________________________________________ Teresa L. Thompson Faculty Advisor Professor of Communication __________________________________________________ James D. Robinson Faculty Reader Professor of Communication __________________________________________________ Ronda M. Scantlin Faculty Reader Associate Professor of Communication ii © Copyright by Allison Marie Lewis All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT AN EXAMINATION OF DISABILITY STEREOTYPES IN MEDICAL DRAMAS BEFORE AND AFTER THE PASSAGE OF THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT (ADA) Name: Lewis, Allison Marie University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Teresa Thompson This study involved the collection and analysis of data coded from medical dramas that aired before the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and after the enactment. Specifically, the study looked at Medic, Marcus Welby, Ben Casey, Emergency, Dr. Kildare (all pre-ADA), and ER, Grey’s Anatomy, China Beach, Chicago Hope, Mercy, and Becker (all post-ADA) to determine whether the ADA served as a turning point in the representation of people with disabilities on medical dramas from 1954 to 2014. A content analysis was conducted to investigate the occurrence of potentially stereotypical communication patterns and behaviors among characters with disabilities and those who interact with them as well as the prevalence of common disability stereotypes throughout the years studied.