Understanding and Appreciating the Wonder Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Award Winner Kristin Chenoweth (You're a Good Man

THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF HALLMARK CHANNEL’S ‘COUNTDOWN TO CHRISTMAS’ AND HALLMARK MOVIES & MYSTERIES’ ‘MIRACLES OF CHRISTMAS’ WILL BE THE BEST CHRISTMAS EVER Original Movie Premieres Every Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday Night BEVERLY HILLS, CA – July 26, 2019 – This holiday, original movie premieres will be on Thursday and Friday on Hallmark Movies & Mysteries’ “Miracles of Christmas” and Saturday and Sunday during Hallmark Channel’s 10th anniversary of “Countdown to Christmas.” Across the networks there will be 40 original movie premieres. On Hallmark Channel, Tony® and Emmy® Award winner Kristin Chenoweth (You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, “Pushing Daisies”) and Scott Wolf (“Party of Five”) star in the Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation of “A Christmas Love Story”; Lacey Chabert (Mean Girls) and Sam Page (“The Bold Type”) find romance in the City of Lights in “Christmas in Rome”; while Candace Cameron Bure (“Fuller House”) and Tim Rozon (“Schitt’s Creek”) find themselves in “Christmas Town.” On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, Nikki Deloach (“Awkward”) and Michael Rady (“Timeless”) team up again for “Two Turtle Doves”; Marc Blucas (“The Fix”), Melissa Claire Egan (“The Young and the Restless”) and Patti Murin (Frozen, “Chicago Med”) star in “Holiday for Heroes”; and Grammy Award winner Amy Grant stars in the all-new movie, “When I Think of Christmas.” The announcement was made today as part of Crown Media Family Networks’ bi-annual Television Critics Summer Press Tour. “Each year our holiday movie slates get bigger, the movies get better, and the ratings grow stronger and I have no doubt that this will prove to be the most successful season yet,” said Michelle Vicary, EVP, Programming & Network Publicity. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

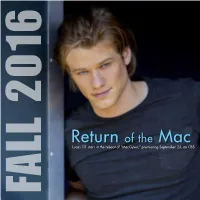

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

Societal Relevance As Success Factor of TV Series: the Creators’ Perception

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Societal relevance as success factor of TV series: the creators’ perception Verhoeven, Marcel Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-170818 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Verhoeven, Marcel. Societal relevance as success factor of TV series: the creators’ perception. 2019, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. Societal Relevance as Success Factor of TV Series: The Creators’ Perception Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University of Zurich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Marcel Verhoeven Accepted in the Spring Term 2019 on the Recommendation of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. Dr. Gabriele Siegert (main advisor) Prof. Dr. M. Bjørn von Rimscha (second advisor) Zurich, 2019 0 Abstract Media mediate societally relevant messages in formats that disseminate information. However, the communication of ideas and opinions on societal issues also takes place in entertainment formats such as fictional TV series. Furthermore, mediation in entertainment is often regarded as more effective than dissemination through information formats, (also) due to the evading of recipients’ selection barriers. The importance of investigating TV series bases on the format’s large narrative space that enables the communication and repetition of ideas and messages and on the format’s popularity with audiences and, consequently, with broadcasters. Countless different influences shape the composition of TV series’ content and the inclusion of societally relevant messages. One potentially very important reason for incorporating specific messages and content elements in TV series is the extent to which decision-makers regard societal relevance as a success factor. -

Resume for Union

David Combs Studio Teacher/Welfare Worker (Union--IA Local #884) Also available for non-union work 4231 West 135th Street, Hawthorne, CA 90250 (cell) 530-409-1188 (home) 818-782-9000 BA: University of California -- Santa Cruz: Comparative French and Spanish Literature/Psycho Linguistics. Lifetime Secondary Credential, CA, Permanent Multi-Subject Credential, CA; 5th Degree French Studies, University of Paris. 7-12 GRADE HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER – EL DORADO COUNTY OFFICE OF EDUCATION French 1-4, Spanish 1-4, Latin 1-4, AP English, Drama and Film History TELEVISION (Lead Teacher): • SCORPION (CBS) Lead Teacher, Riley Smith, all subjects grade 4 plus Introduction to Italian • THE MIDDLE (WARNER TELEVISION) Re: curring Role Teacher: 7TH through 12th grade curricula plus Spanish I, II and French I, II • GROWING UP FISHER (NBC/UNIVERSAL) Lead Teacher: Eli Baker, Lance Lim, Isabel Moner: all subjects grades 7 through 9 plus Spanish I and II • BACK IN THE GAME (ABC/FOX) Lead Teacher: Griffin Gluck, and 9 baseball team members. Grades 5 through 7 all subjects plus French III and Latin I, II • PRIVATE PRACTICE (ABC PRODUCTIONS) Lead Teacher: Griffin Gluck; all subjects taught in French in preparation for French Baccalaureat • FRESH OF THE BOAT (FOX) Background Teacher, all levels • MARRY ME (PARAMOUNT) Background Teacher, all levels • GLEE (PARAMOUNT) Background Teacher, all levels • GIRL MEETS WORLD (IT’S A LAUGH PRODUCTIONS) Background Teacher • BOY MEETS WORLD (Disney): Ben Savage, Rider Strong, Will Friedle, Danielle Fishel, Lindsay Ridgeway: all -

Allendale Lifelong Learners December 2020

Allendale Lifelong Learners December 2020 In this issue: From the Director’s Desk • All Things Michigan I’m sure you’re feeling the frustrations of Covid restrictions as much as I • Calendar of events am. But even in the midst of all the disappointment and unknowns, I’m looking for new ways to make memories and be a light in the darkness. • Updates and nonsense And as the weather is turning cooler, the masks are actually a source of warmth and comfort. Choose to make the best of your situation. It will • Volunteer Opportunities make such a difference. Here are some fun and unique ways to see some pretty awesome Christ- • Activities in the mas lights/decorations that are local and free!!! Two of my favorite Community things! Starting Friday, November 27: • The Rest of the Story Lights and Music yard display: 12385 92nd Avenue, Allendale. It’s • worth a drive to see this light show that is set to music. Pull up and tune your radio to see and hear a well coordinated light display. Located at the corner of 92nd and Warner. Every night through the end of the year. Christmas Tree Walk: Life Stream Church is hosting a Christmas Tree Walk that is open nightly, through the end of the year. Friday and Satur- day nights from 6 to 8 PM there will be special activities such as food trucks, hot cocoa, dance troupe (December 12), live nativity (December 18). This is a festive and fun event at a time we could all use a little pick -me-up! Bring a canned good for entry . -

Women's Leadership in Primetime Television an Introductory Study

Women’s Leadership in Primetime Television An Introductory Study Natalie Greene Spring 2009 General University Honors Capstone Advisor: Karen O’Connor Greene 1 Women’s Leadership in Prime-time Television: An Introductory Study Introduction When television executives report their core audience, women always come out ahead. A 2007 Nielsen Media Research report showed that, with only two exceptions, every broadcast network channel had more female viewers than men. ABC’s female audience almost doubled its male audience during the 2007-08 season (Atkinson, 2008). 1 Women onscreen, however, seem to reflect a different reality, making up only 43% of characters in the prime-time 2007-08 season (Lauzen, 2008). 2 As studies going back as far as the 1970s show, women on screen not only fail to represent the proportional makeup of women in society, they also overwhelmingly show a stereotypically gendered version of women (McNeil, 1975; Signorielli and Bacue, 1999; United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1977). This paper aims to address the evolution of women’s leadership in prime-time network scripted television from 1950 to 2008. Because of the way that women have been traditionally marginalized in television, it is important to study the shows that have featured women as lead characters. Characters such as Lucy Ricardo ( I Love Lucy, 1951-1960) influenced later female leads such as Ann Marie ( That Girl, 1966-1971), Mary Richards ( The Mary Tyler Moore Show, 1970-1977) and Murphy Brown ( Murphy Brown, 1988-1998). Thus, along with an introduction to socialization theory and feminist television criticism, this paper covers a selection of some of the most influential female characters and women-centered shows of this period. -

Download the Wonder Years

The wonder years! by P. Ravi Shankar The house was old but had personality! The small space in front paved with red rectangular tiles, the arched doorway with red bougainvilleas growing in riotous profusion, the well by the side and the small garage filled with sand. White jasmine bushes wafted their heady scent into the night air filling the house with an intoxicating fragrance. The drawing room and the kitchen, the nerve centers of the house adjoined each other. My father used to always say that this arrangement ensured that the ladies of the house could keep an eye on the main entrance from the kitchen. The drawing room had wooden windows with colored glass panes. Dark blue, green, and violet panes tinted the entering light in rich colors. The roof had wooden rafters and the floor was a dark, warm, rich red. There was a wooden showcase encasing a beautiful image of Lord Krishna which used to dominate the room. In the modern era the LCD television has pride of place in most drawing rooms and sadly the same has occurred in my father’s ancestral home. My grandmother was a remarkable woman. She was small, around five feet one; as she aged her spine gently curved dragging her closer to Mother Earth. She was always immaculately dressed in white and was perpetually busy with household matters. She was a matriculate under the old British system and used English precisely and succinctly. She had studied in Moyan Girls High School in Palakkad, Kerala during the 1920s and 30s and it was a strange quirk of fate that over sixty years later I appeared for the medical entrance exam successfully at the same school where my grandmother had studied. -

The Wonder Years Is a Great Resource for Women's Book Clubs, Sunday

The Wonder Years is a great resource for women’s book clubs, Sunday School classes, small group studies and online book clubs. In our youth- addled world, age is one of the last taboos, seldom spoken of in public, even in our churches. ( I know. I’m the one who lied about my age on Facebook. For a month.) But finally, we have an honest, beautiful theologically rich resource to guide our conversations about this passage through the middle and later decades of our lives. So---for the many who have asked for a study guide, here it is! Here’s how it works. Since the book is divided into three sections: Firsts, Lasts and Always, the study guide here is designed as a 6 week series, so you’ll spend two weeks per section. Or, to say it another way, each week you’ll consider half of the essays in each section. That’s moving at a pretty fast clip, so those of you who want to slow down to squeeze out ALL the juice, I hope you’ll do exactly that, and move at your own pace. For those of you doing an online study, feel free to pick and choose among these questions. Whatever you choose and however you do it, I know you’ll have rich, raw, cathartic challenging fun as you think and speak your way through these essays with a community of like-minded and like-hearted women. Here we go! SESSION ONE 1. In the Introduction I reference Tirah Harpaz’s landmark essay in Salon.com entitled “Women Over 50 Are Invisible.” https://www.salon.com/2013/04/05/wanna_know_what_its_like_t o_disappear_try_being_a_woman_over_50_partner/ Do you agree with her thesis? When do you feel most invisible---and why? 2. -

Rank Series T Title N Network Wr Riter(S)*

Rank Series Title Network Writer(s)* 1 The Sopranos HBO Created by David Chase 2 Seinfeld NBC Created by Larry David & Jerry Seinfeld The Twilighht Zone Season One writers: Charles Beaumont, Richard 3 CBS (1959)9 Matheson, Robert Presnell, Jr., Rod Serling Developed for Television by Norman Lear, Based on Till 4 All in the Family CBS Death Do Us Part, Created by Johnny Speight 5 M*A*S*H CBS Developed for Television by Larry Gelbart The Mary Tyler 6 CBS Created by James L. Brooks and Allan Burns Moore Show 7 Mad Men AMC Created by Matthew Weiner Created by Glen Charles & Les Charles and James 8 Cheers NBC Burrows 9 The Wire HBO Created by David Simon 10 The West Wing NBC Created by Aaron Sorkin Created by Matt Groening, Developed by James L. 11 The Simpsons FOX Brooks and Matt Groening and Sam Simon “Pilot,” Written by Jess Oppenheimer & Madelyn Pugh & 12 I Love Lucy CBS Bob Carroll, Jrr. 13 Breaking Bad AMC Created by Vinnce Gilligan The Dick Van Dyke 14 CBS Created by Carl Reiner Show 15 Hill Street Blues NBC Created by Miichael Kozoll and Steven Bochco Arrested 16 FOX Created by Miitchell Hurwitz Development Created by Madeleine Smithberg, Lizz Winstead; Season One – Head Writer: Chris Kreski; Writers: Jim Earl, Daniel The Daily Show with COMEDY 17 J. Goor, Charlles Grandy, J.R. Havlan, Tom Johnson, Jon Stewart CENTRAL Kent Jones, Paul Mercurio, Guy Nicolucci, Steve Rosenfield, Jon Stewart 18 Six Feet Under HBO Created by Alan Ball Created by James L. Brooks and Stan Daniels and David 19 Taxi ABC Davis and Ed Weinberger The Larry Sanders 20 HBO Created by Garry Shandling & Dennis Klein Show 21 30 Rock NBC Created by Tina Fey Developed for Television by Peter Berg, Inspired by the 22 Friday Night Lights NBC Book by H.G.