Medieval Whitchurch: the Origins of a New Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Martin's Church East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition Of

ST MARTIN’S CHURCH EAST WOODHAY INDEX, CATALOGUE AND CONDITION OF MEMORIAL AND OTHER INSCRIPTIONS 1546-2007 Prepared by Graham Heald East Woodhay Local History Society 2008 Developed from the 1987 Catalogue prepared by A C Colpus, P W Cooper and G G Cooper Hampshire Genealogical Society An electronic copy of this document is available on the Church website www.hantsweb.gov.uk/stmartinschurch First issue: June 2005 Updated and minor corrections: February 2008 St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition of Memorial Inscriptions, 1546 - 2007 CONTENTS Page Abbreviations 1 Plan of Memorial Locations 2 Index 3 Catalogue of Inscriptions and Condition Churchyard, Zone A 11 Churchyard, Zone B 12 Churchyard, Zone C 15 Churchyard, Zone D 28 Churchyard, Zone E 29 Churchyard, Zone F 39 Churchyard, Zone G 43 Church, East Window 45 Church, North Wall (NW) 45 Church, South Wall (SW) 48 Church, West Wall (WW) 50 Church, Central Aisle (CA) 50 Church, South Aisle (SA) 50 Pulpit, Organ and Porch 51 Memorials located out of position (M) 51 Memorials previously recorded but not located (X) 52 The Stained Glass Windows of St Martin’s Church 53 St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay Index, Catalogue and Condition of Memorial Inscriptions, 1546 - 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Form of Memorial CH Cross over Headstone CP Cross over Plinth DFS Double Footstone DHS Double Headstone FS Footstone HS Headstone K Kerb (no inscription) Kerb KR Kerb and Rail (no inscription) PC Prostrate Cross Plinth Slab Slab (typically 2000mm x 1000mm) SS Small Slab (typically 500mm -

North West Hampshire Benefice Ashmansworth + Crux Easton + East Woodhay + Highclere + Woolton Hill

1 North West Hampshire Benefice ASHMANSWORTH + CRUX EASTON + EAST WOODHAY + HIGHCLERE + WOOLTON HILL . making Christ known in our communities Profile for an Associate Priest North West Hampshire Benefice 1 ASHMANSWORTH + CRUX EASTON + EAST WOODHAY + HIGHCLERE + WOOLTON HILL . making Christ known in our communities Welcome! Welcome to this Benefice Profile and Role Description… and welcome to the Diocese of Winchester! At the heart of our life here is the desire to be always Living the Mission of Jesus. We are engaged in a strategic process to deliver a mission-shaped Diocese, in which parochial, pastoral The Diocese of and new forms of pioneering and radical ministry all flourish. Infused with God’s missionary Spirit we want three character traits to be clearly Winchester is an visible in how we live: exciting place to be . North West • Passionate personal spirituality Hampshire Benefice • Pioneering faith communities • Prophetic global citizens The Diocese of Winchester is an exciting place to be at the moment. We wait with eager anticipation to see how this process will unfold. We pray that, if God is calling you to join us in his mission in this part of the world, he will make his will abundantly “As the Father sent clear to you. me so I send you www.winchester.anglican.org/resources-archive/?s=&resourcecategory=mission- . Receive the action-planning Spirit” (John 20:21) Tim Dakin David Williams Bishop of Winchester Bishop of Basingstoke we are developing our Whitchurch Deanery is as beautiful as any other part of Hampshire, an area of rolling capacity to support each downland in the north together with the upper Test valley, bounded by the Berkshire border other and to engage and the A303. -

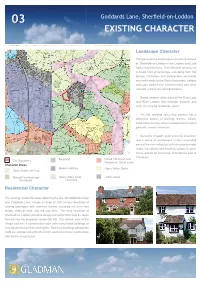

Goddards Lane, Sherfield-On-Loddon Statement of Community Involvement

03 *RGGDUGV/DQH6KHUÀHOGRQ/RGGRQ EXISTING CHARACTER Landscape Character The site lies immediately adjacent to the settlement RI6KHU¿HOGRQ/RGGRQLQWKH/RGGRQDQG/\GH Valley character area. This character area covers a broad tract of landscape extending from Old Basing, Chineham and Basingstoke eastwards and northwards to the District boundary. Loddon and Lyde Valley’s key characteristics and other relevant extracts are provided below: %URDGVKDOORZYDOOH\VLGHVRIWKH5LYHU/\GH and River Loddon that meander through, and unify, the varying landscape types; 7KHÀDWORZO\LQJYDOOH\ÀRRUSDVWXUHKDVD GLVWLQFWLYH SDWWHUQ RI GUDLQDJH GLWFKHV ZLOORZ lined watercourses, water meadows and an often pastoral, remote character; *HQHUDOO\XQVSRLOWTXLHWDQGUXUDOFKDUDFWHU and a sense of remoteness in less accessible parts of the river valley, but with intrusion by major roads, the railway and electricity pylons in some areas, and by an incinerator immediately east of Chineham Mixed Farmland and Site Boundary Parkland Woodland: Small scale Character Areas Modern Military Open Valley Sides Open Arable on Clay Mixed Farmland and Open Valley Floor Urban areas Woodland Farmland Residential Character The existing residential areas adjoining the site off Goddards Close and Goddards Lane include a range of 20th century dwellings of varying typologies with common themes including red brick and render; roofs of slate; and red clay tiles. The local character of 6KHU¿HOGRQ/RGGRQSURYLGHVGHVLJQHOHPHQWVWKDWFRXOGEHWDNHQ forward into the proposed residential site. The historic core -

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Baughurst House, Wolverton Townsend, Baughurst Hants, RG26 5SS

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Baughurst House, Wolverton Townsend, Baughurst Hants, RG26 5SS Proposed Re-alignment of Entrance Drive November 2016 PREPARED BY: PRO VISION PLANNING & DESIGN FOR AND ON BEHALF OF: Mr & Mrs S Hall HERITAGE ASSESSMENT BAUGHURST HOUSE, WOLVERTON TOWNSEND, BAUGHURST, HANTS RG26 5SS PROJECT NO. 2179/DRIVE PREPARED BY: ANDREW PATRICK DiplArch(Portsmouth) DipTP RegdArcht CONSULTANT CHECKED BY: JAMES CLEARY DIRECTOR DATE: NOVEMBER 2016 PRO VISION PLANNING AND DESIGN GROSVENOR COURT WINCHESTER ROAD AMPFIELD WINCHESTER HAMPSHIRE SO51 9BD COPYRIGHT: The contents of this document must not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior written consent of PV Projects. CONTENTS Page 1.0 Introduction & Summary 1 2.0 Overview 2 3.0 Driveways: Existing, Proposed and Heritage Impact Assessment 7 Appendices Appendix A: Site Plan As Existing Appendix B: Site Plan as Proposed Appendix C: Photographs 1 1.0 Introduction & Summary 1.1 Pro Vision Planning & Design are instructed by Mr & Mrs S Hall to assess the potential heritage impact of the proposed re-alignment of the main entrance drive to Baughurst House, Wolverton Townsend, Baughurst, Hants. Wolverton Townsend is the name of the lane from Pound Green to Townsend and Wolverton. 1.2 This Heritage Statement therefore:- a) Outlines relevant information on the overall complex of buildings and grounds at Baughurst House, as the context for the assessment; b) Describes the existing driveways; c) Describes the proposed re-alignment; and d) Assesses the proposed change in light of the listed status of the house and the relationship of the existing and proposed drives to its special architectural and historic interest and its setting. -

29.08.2021 Weekly Intercessions

THE PARISH OF THE HOLY TRINITY CHRISTCHURCH WEEKLY INTERCESSIONS Week beginning Sunday 29th August 2021 THE THIRTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY PLEASE REMEMBER IN YOUR PRAYERS: PARISH INTERCESSIONS: The sick or those in distress: Phil Aspinall, Brian Barley, Chris Calladine, Isla Drayton, John Franklin, Iain, Marion Keynes, Gill de Maine, Geoffrey Owen, Eileen Parkinson, Richard Passmore, Lynn Pearson, Roméo Ronchesse, Paul Rowsell, Sandra, Sia, Betty Sullivan, The long term sick: Brian Keemer, Denise Wall The housebound and infirm: Those recently departed: Karen Baden, Elizabeth Barr, Brenda Woodward Those whose anniversary of death falls at this time: Christine Sadler (30th), Susan Roberts (1st September), Eileen Wall (1st), Patricia Devall (1st), Joy Saberton (2nd), Daniel Whitcher (4th) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ANGLICAN COMMUNION & WINCHESTER DIOCESE AND DEANERY INTERCESSIONS: Sunday 29th August The Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity Anglican Cycle: South Sudan: Justin Badi Arama (Archbishop, and Bishop of Juba) Diocesan Life: Chaplaincy: lay and ordained, in prisons, schools, universities, police, hospitals and in our communities; and Anna Chaplains working with older people and chaplains working with those with disability, the deaf & hard of hearing. Deanery: The Area Dean, Canon Gary Philbrick. The Assistant Area Dean , Matthew Trick, The Lay Chair of Synod, Susan Lyonette. Members of the Standing Committee. The Deanery Synod and our representatives on the Diocesan Synod. Kinkiizi Prayers : Kanyantorogo Archdeaconry. Monday 30th August John Bunyan, Spiritual Writer, 1688 Anglican Cycle: Ekiti Kwara (Nigeria): Andrew Ajayi (Bishop) Diocese: Benefice of Burghclere with Newtown and Ecchinswell with Sydmonton: Burghclere: The Ascension; Ecchinswell w Sydmonton: St Lawrence; Newtown: St Mary the Virgin & St John the Baptist. Clergy & LLMs: Priest in Charge: Anthony Smith. -

St. James' Church, Ashmansworth

ST. JAMES’ CHURCH, ASHMANSWORTH This little church on the Hampshire Downs at the north end of the Winchester Diocese has an intriguing history reaching back into the 10th century. It also has a singular charm as its small white, weatherboard bell tower is sighted above the high banks and hedges of the lane that winds down towards the Bourne Valley. Sadly, the old bells no longer ring out over the scattered village - because they must be re-hung before they can even be chimed. (It has, up to now, seemed unlikely that adequate funds will ever be available for full circle ringing). Indeed, this situation is a part of the dilemma facing this small parish, a dilemma created, strangely enough, by a generous bequest from one of its parishioners, Miss Annie Taylor. This bequest led the Parochial Church Council to call in experts to advise on what might be done to restore and make safe the bell tower, to preserve and improve the remains of the wall paintings as well as to repair the effects of sheer age on the church as a whole; which has inevitably taken place despite the devoted attention of church wardens and parishioners over the years. It needs little imagination to recognise that this survey revealed a call for restoration work with costs far exceeding the value of this bequest. The earliest extant reference to Ashmansworth is found in the Charter of King Athelstan the Victorious (925-940) and it is certain that a Saxon church stood on this site of the present building which itself belongs mainly to the 12th century and at that time was mentioned in the general confirmation of his manors by Edward I. -

Sparsholt College Campus Bus Timetable 2021/22

Sparsholt College campus bus timetable 2021/22 Aldershot – Aldermaston - 0118 971 3257 Pick up Drop off Time Price Time (Departs SCH 4.40 pm) Band Aldershot – Train station Road opp Station Cafe 7.55 am 6.25 pm D Heath End - layby, by Camdenwell's Fish Bar 8.00 am 6.25 pm D Farnham -South Street bus stop by Sainsbury's AM/ junction of West Street & Castle Street PM 8.05 am 6.15 pm D Bordon – bus stop on the A325 Farnham Road (East Bound) near Station Rd 8.25 am 5.55 pm D Alton – Sainsbury’s, Draymans Way 8.45 am 5.35 pm C Four Marks - Lymington Bottom Bus Stop 8.55 am 5.25 pm B New Alresford – The Co-op bus stop 9.05 am 5.15 pm B Amesbury - Amport and District – 01264 772307 Pick up Drop off Time Price Time (Departs SCH 4.40 pm) Band Amesbury – Central Car Park 8.30 am 5.50 pm C Bulford Camp - Near Junction of Marlborough Rd/ Horne Rd 8.40 am 5.40 pm C Tidworth – Hampshire Cross bus stop 8.50 am 5.30 pm C Ludgershall - Outside Tesco 8.55 am 5.25 pm B Weyhill Road – Appleshaw (AM) / White House (PM) crossroad 9.00 am 5.15 pm B Weyhill Road – Layby past Short Lane 9.05 am 5.20 pm B Middle Wallop – Junction of The Avenue/Danebury Rd 9.15 am 5.05 pm B Stockbridge – St Peters Church 9.20 am 4.50 pm A Bitterne - Wheelers - 02380 471800 Pick up Drop off Time Price Time (Departs SCH 4.50 pm) Band Bitterne – West End Rd, opposite Sainsbury’s 7.45 am 6.15 pm B Portswood – bus stop outside Bus Depot, now Sainsbury’s 8.00 am 6.00 pm B Chilworth -Roundabout at Bassett Avenue (AM); 1st bus stop The Avenue after pedestrian lights (PM) 8.15 am 5.45 pm -

Basingstoke Rural West Covering the Wards Of: Baughurst and Tadley North; Kingsclere; Sherborne St John; Burghclere, Highclere and St Mary Bourne; East Woodhay

Basingstoke Rural West Covering the wards of: Baughurst and Tadley North; Kingsclere; Sherborne St John; Burghclere, Highclere and St Mary Bourne; East Woodhay www.hampshire.police.uk Welcome to the Basingstoke Rural West Newsletter, November 2019 Your neighbourhood policing team includes: PC Simon Denton PC Jon Hayes You can contact the team at [email protected] — though this address is not monitored every day. For reporting crime, call 101 or go to the Hampshire police website www.hampshire.police.uk. Community Priorities The current neighbourhood priority is Burglary. A residential property in Cannon Heath, Overton, was broken into during daylight hours and jewellery was stolen. An electric bike was stolen from a garage in Ecchinswell. Some facts about burglaries (sources in brackets). Most burglaries take place between 10am and 3pm. (Safestyle UK) The average burglary lasts for eight minutes. (Dr Claire Nee, Unviersity of Portsmouth) Many burglaries are ‘spur of the moment’ decisions by a burglar who notices an open door, open window, valuables on display or some other weakness. (Thames Valley Police) The vast majority of burglars will want to avoid meeting the home’s occupants at any cost. (The Independent) A burglar may typically examine many houses before finding one that looks like an easy one to steal from. Homes with no security measures in place are five times more likely to be burgled than those with simple security measures. Good window locks and strong deadlocks can make a big difference. In most burglaries, the criminals broke into the house or flat through the door, either by forcing the lock or kicking it in. -

Appendix 3 Formal Resolution

Appendix 3 Formal Resolution Council Taxes for the year ending 31 March 2022 1. The recommended council tax requirement for the Borough Council’s own purposes (and excluding Parish precepts) is £8,756,147 2. It be noted that the Section 151 Officer (Executive Director of Corporate Services) on 08 January 2021 calculated the Council Tax Base for 2021/22 for the whole Borough area as 66,627.2 (Item T in the formula in Section 31B of the Local Government Finance Act 1992) and, for dwellings in those parts of its area to which a Parish precept relates as per Appendix 2 (column 3). 3. That the following amounts be now calculated by the Council for the year 2021/22 in accordance with Sections 31 to 36 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992 and subsequent regulations: (a) £142,474,348.00 being the aggregate of the amounts which the Council estimates for the items set out in Section 31A(2) of the Act taking into account all precepts issued to it by Parish Councils. (b) £132,169,900.00 being the aggregate of the amounts which the Council estimates for the items set out in Section 31A(3) of the Act. (c) £10,304,448.00 being the amount by which the aggregate at 3(a) above exceeds the aggregate at 3(b) above, calculated by the Council in accordance with Section 31A(4) of the Act as its council tax requirement for the year. (Item R in the formula in Section 31B of the Act). (d) £154.66 being the amount at 3(c) above (Item R), all divided by Item T (2 above), calculated by the Council, in accordance with Section 31B(1) of the Act, as the basic amount of its Council Tax for the year (including Parish precepts). -

Browns Farm Pound Green, Ramsdell, Hampshire

Browns Farm Pound Green, Ramsdell, Hampshire Browns Farm Pound Green, Ramsdell, Hampshire Most attractive Grade II listed Hampshire farmhouse with separate cottage and outbuildings. Kingsclere 3 miles, Basingstoke 8 miles, Newbury 10½ miles, Reading 14½ miles, M3 (Junction 6) 9 miles M4 (Junction 13) 14½ miles, London Waterloo via Basingstoke Station from 45 minutes (All distances and times are approximate) Accommodation and amenities Hall | Drawing room | Sitting room | Dining room | Kitchen/breakfast room | Study | Cloakroom | Master bedroom with walk-in wardrobe and en suite bathroom | 4 further bedrooms | Family bathroom Planning application submitted to extend to provide two further bedrooms and bathroom and to enlarge the kitchen/breakfast room Browns Cottage 4 bedrooms | Garaging | Office Period Barn Stable | Store room | Garden machinery store | Workshop | Attic with potential for games room or storage Mature gardens | Paddock land | Hard tennis court In all about 1.214 hectares (3 acres) Basingstoke Matrix House, Basing View Basingstoke RG21 4FF Tel: 1256 630 978 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Browns Farm is situated in a superb rural position approximately 1½ miles north of Ramsdell, a popular village in this sought after location which lies between the towns of Basingstoke and Newbury. Day-to-day shopping requirements can be found in Kingsclere and Tadley. There are public houses at Charter Alley and Wolverton Townsend, as well as the popular Wellington Arms public house/restaurant in Baughurst. The major regional centres of Basingstoke, Reading and Newbury have a broad range of shopping, recreational and educational facilities and are all within easy reach. Despite its rural location, communications within the area are excellent with a mainline railway station at Basingstoke and easy access to both the M3 and M4 motorways providing good road access to London, the South Coast, the West Country and Heathrow and Gatwick airports. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

The Quaker Burial Grounds at Baughurst, — ':'-•

4 ° '-..•• ,s. • THE QUAKER BURIAL GROUNDS AT BAUGHURST, — ':'-• BY FLORENCE A. G. DAVIDSON. .. It was not long after George Fox, the founder of the Community of Friends, began his active ministry, in 1648, that we begin to find traces of his teaching in many parts of Hampshire. His followers were at first few in number, and this new religion was so persecuted and proscribed that its members had to conduct their meetings in secrecy; and it is owing to this fact that so many details of their early discipleship have been lost sight of and tradition concerning them died out of the County. To-day all trace of the Quakers has died out of the villages round about, but in Baughurst we still find many traces of them. The Community here, at the end of 1600, seems to have been a rather large and also an influential one and included members from Kingsclere, Aldermaston, Sherfield, Tadley, Itchingswell, &c. Mr. Richard Potter, who lived in what is known as Brown's Farm (now forming part of the Baughurst House estate) was one of their leading members, together with Mr. John Harris, of Baughurst House, who had married one of Mr. Potter's family. Mr. Potter greatly enlarged and added to the farm house from a still older one on the same site, and it stands to-day practically the same now as then. On the central gable is the date 1693, and the initials R. P. M. for Richard and Mary Potter, his wife ; while A. N. for Ann Potter is on the south chimney.