Interview # 85 –Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy -name redacted- Specialist in African Affairs October 5, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42774 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy Summary Congress has played an active role in U.S. policy toward Sudan for more than three decades. Efforts to support an end to the country’s myriad conflicts and human rights abuses have dominated the agenda, as have counterterrorism concerns. When unified (1956-2011), Sudan was Africa’s largest nation, bordering nine countries and stretching from the northern borders of Kenya and Uganda to the southern borders of Egypt and Libya. Strategically located along the Nile River and the Red Sea, Sudan was historically described as a crossroads between the Arab world and Africa. Domestic and international efforts to unite its ethnically, racially, religiously, and culturally diverse population under a common national identity fell short, however. In 2011, after decades of civil war and a 6.5 year transitional period, Sudan split in two. Mistrust between the two Sudans—Sudan and South Sudan—lingers, and unresolved disputes and related security issues still threaten to pull the two countries back to war. The north-south split did not resolve other simmering conflicts, notably in Darfur, Blue Nile, and Southern Kordofan. Roughly 2.5 million people remain displaced as a result of these conflicts. Like the broader sub-region, the Sudans are susceptible to drought and food insecurity, despite significant agricultural potential in some areas. -

A Walk Through the Gallery 5

A WALK THROUGH THE GALLERY MARGARET PLASS The new African Gallery has been designed to exhibit, simply and honestly, a selection of sculptures from our permanent collections. Proudly we present them as works of art; where possible they are arranged in tribal groups for convenience and comparative study. They are labeled briefly and clearly. Here are the materials from which our visitors may form a just view of the special characteristics and merits of Negro art. For more than half a century our Museum has been enriched by acces- sions of African sculpture, mainly by purchase and partly by gifts, to the end that our permanent collections are the largest and most varied in style in America. The following descriptive notes are not to be construed as an attempt at a catalogue of the exhibition; the serious student may have access to fully documented formal catalogues should he apply to the Museum staff. In Dr. Coon's introduction he has given us the anthropological and ethno- grapbical background of the people who produced this art, working within the framework of their tribal traditions. Here in this book, with their photographs, are small synopses of what we know of these sculptures, and what we guess. We all have conscious, and sometimes unconscious, difficulty in understanding such works of art; the philosophical barrier that lies in the way of full appreciation is almost too difficult to hurdle. Many writers have tried to explain the magico-religious significance, the strength and directness of African art; few have succeeded. Perhaps these notes are mere hints and suggestions, but we hope that they may sometimes be stimulating as well as factual. -

Unrivalled Art

EN Temporary exhibition UNRIVALLED ART Curator Julien Volper A 109 HOW TO USE THE BOOKLET • The numbers on the showcases match the page numbers in the booklet. - Numbers on top of the showcase refer to the theme. See p. 88 - Numbers on the bottom of the glass panels provide information on objects. See p. 43 • You can also download this booklet using the QR code below or on www.africamuseum.be A MASKS For more than fifty years, a large mask – half human, half animal – was the symbol of this museum. Most Congolese masks take the form of a human or an animal, or a mix of the two. Just as with statues, the style varies from the most breathtaking naturalism, to minimalism, to total abstraction. What we are showing here in the display cases – the faces – is only a part of what the Congolese public could see. The wearers were also dressed in costumes and sometimes carried accessories. Some shook their ankle bells and danced a choreography to the rhythm of the musicians. Isolated from costume and context, these faces on display have lost a large part of their identity. Depending on the culture that a mask belonged to, it performed alone or in company. Some had a precisely defined identity, while others were widely deployed. Most masks had a connection with the world of the dead or with the world of nature spirits. They only performed at important oc- casions or at established ritual moments. In the first half of the 20th century, masks were increasingly used on festive and profane occasions - if they did not entirely disappear from the scene. -

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and US Policy

Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs October 5, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42774 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Sudan and South Sudan: Current Issues for Congress and U.S. Policy Summary Congress has played an active role in U.S. policy toward Sudan for more than three decades. Efforts to support an end to the country’s myriad conflicts and human rights abuses have dominated the agenda, as have counterterrorism concerns. When unified (1956-2011), Sudan was Africa’s largest nation, bordering nine countries and stretching from the northern borders of Kenya and Uganda to the southern borders of Egypt and Libya. Strategically located along the Nile River and the Red Sea, Sudan was historically described as a crossroads between the Arab world and Africa. Domestic and international efforts to unite its ethnically, racially, religiously, and culturally diverse population under a common national identity fell short, however. In 2011, after decades of civil war and a 6.5 year transitional period, Sudan split in two. Mistrust between the two Sudans—Sudan and South Sudan—lingers, and unresolved disputes and related security issues still threaten to pull the two countries back to war. The north-south split did not resolve other simmering conflicts, notably in Darfur, Blue Nile, and Southern Kordofan. Roughly 2.5 million people remain displaced as a result of these conflicts. Like the broader sub-region, the Sudans are susceptible to drought and food insecurity, despite significant agricultural potential in some areas. -

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART to LIFE By

ELIOT ELISOFON: BRINGING AFRICAN ART TO LIFE by KATHERINE E. FLACH Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Dr. Constantine Petridis, Co-Advisor Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Katherine E. Flach ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Catherine B. Scallen (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Constantine Petridis ________________________________________________ Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Jonathan Sadowsky ________________________________________________ DATE OF DEFENSE March 4, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 This dissertation is dedicated to my family John, Linda, Liz and Sam 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 11 Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 12 Eliot Elisofon and African Art: An Introduction ........................................................ 14 Elisofon and LIFE ...................................................................................................... -

Sudan, December 2004

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Sudan, December 2004 COUNTRY PROFILE: SUDAN December 2004 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of the Sudan (Jumhuriyat as-Sudan). Short Form: Sudan. Term for Citizen(s): Sudanese. Capital: Khartoum. Other Major Cities: Omdurman, Khartoum North, Port Click to Enlarge Image Sudan, Kassala, Al Ubayyid, and Nyala (according to decreasing size, 1993 census). Independence: Sudan gained independence from the United Kingdom and Egypt on January 1, 1956. Public Holidays: Sudan observes the following public holidays: Independence Day (January 1, 2004), Feast of the Sacrifice/Id al-Adha (February 1, 2004*), Islamic New Year (February 22, 2004*), Uprising Day, anniversary of 1985 coup (April 6, 2004), Coptic Easter Monday/Sham an-Nassim (April 12, 2004*), Birth of the Prophet/Mouloud (May 2, 2004*), Revolution Day (June 30, 2004), end of Ramadan/Id al-Fitr (November 14, 2004*), and Christmas (December 25, 2004). The asterisk indicates holidays with variable dates according to the Islamic or Coptic calendar. Flag: Sudan’s flag has three horizontal bands of red (top), white, and black with a green isosceles triangle based on the hoist side. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Click to Enlarge Image Prehistory and Early History: Northern Sudan was inhabited by hunting and gathering peoples by at least 60,000 years ago. These peoples had given way to pastoralists and probably agriculturalists at least by the fourth millennium B.C. Sudan’s subsequent culture and history have largely revolved around relations to the north with Egypt and to the south with tropical Africa, the Nile River forming a “bridge” through the Sahara Desert between the two. -

Republic of South Sudan

"Southern Sudan" redirects here. For the former autonomous regions of Sudan, see Government of Southern Sudan (1972–1983) and Government of Southern Sudan (2005–2011). Republic of South Sudan Flag Coat of arms Motto: "Justice, Liberty, Prosperity" Anthem: "South Sudan Oyee!" Capital Juba (and largest city) 04°51′N 31°36′E4.85°N 31.6°E [1][2] Official language(s) English Recognized All South Sudanese national languages indigenous languages[3] Demonym South Sudanese Federal presidential Government democratic republic - President Salva Kiir Mayardit - Vice President Riek Machar Legislature National Legislature - Upper House Council of States - Lower House National Legislative Assembly Independence from Sudan - Comprehensive Peace 6 January 2005 Agreement - Autonomy 9 July 2005 - Independence 9 July 2011 Area - 619,745 km2 (45th) Total 239,285 sq mi Population - 2008 census 8,260,490 (disputed)[4] (94th) GDP (nominal) 2011 estimate - Total $13.227 billion [5] - Per capita $1,546 [5] Currency South Sudanese pound (SSP) Time zone East Africa Time (UTC+3) Drives on the right ISO 3166 code SS .ss[6] (registered but not yet Internet TLD operational) [7] Calling code +211 South Sudan ( i/ˌsaʊθ suːˈdæn/ or /suːˈdɑːn/), officially the Republic of South Sudan,[8] is a landlocked country usually considered to be a part of North Africa[9] or Eastern Africa. Its current capital is Juba, which is also its largest city; the capital city is planned to be moved to the more centrally-located Ramciel in the future.[10] South Sudan is bordered by Ethiopia to the east, Kenya to the southeast, Uganda to the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the southwest, the Central African Republic to the west, and Sudan to the north. -

NPA's All-Female Demining Team in Sudan

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 12 Issue 2 The Journal of ERW and Mine Action Article 7 March 2008 NPA’s All-female Demining Team in Sudan CISR JOURNAL Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU (CISR) Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation JOURNAL, CISR (2008) "NPA’s All-female Demining Team in Sudan," The Journal of ERW and Mine Action : Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol12/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOURNAL: NPA’s All-female Demining Team in Sudan under the auspices of the CMAA. Howev- However, if this pigeonholing is what the gender be accomplished in a comprehensive manner er, several problems mar the effectiveness of aspects of the mine-action strategies of the CMAA without including a gendered component that is these initiatives. First of all, “gender” seems amounts to, it does not qualify as mainstreaming mainstreamed through all aspects of the work to be synonymous with “women,” an unfortu- in the real meaning of the concept. of the sector, including the cooperation with NPA’s All-female Demining Team in Sudan nate misconception often encountered when Some efforts are necessary to mend the development organizations and private entities. -

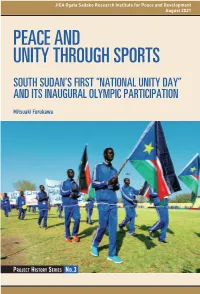

Peace and Unity Through Sports South Sudan’S First “National Unity Day” and Its Inaugural Olympic Participation

JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development August 2021 PEACE AND UNITY THROUGH SPORTS SOUTH SUDAN’S FIRST “NATIONAL UNITY DAY” AND ITS INAUGURAL OLYMPIC PARTICIPATION Mitsuaki Furukawa PROJECT HISTORY SERIES No.3 Peace and Unity through Sports South Sudan’s First “National Unity Day” and its Inaugural Olympic Participation Mitsuaki Furukawa 2021 JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development Cover: March at South Sudan’s First national sports event “National Unity Day” (Photograph courtesy of Ayako Oi) The author would like to thank Drs. Robert D. Eldridge and Graham B. Leonard for their translation of this work. The views and opinions expressed in the articles contained in this volume do not necessarily represent the official view or positions of the organizations the authors work for or are affiliated with. JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development https://www.jica.go.jp/jica-ri/index.html 10-5 Ichigaya Honmura-cho, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 162-8433, JAPAN Tel: +81-3-3269-2357 Fax +81-3-3269-2054 Copyright@2020 JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development. ISBN: 978-4-86357-088-7 Foreword This book is about the efforts to promote “Peace and Unity” through sports in the Republic of South Sudan following its independence in 2011. The author, Mitsuaki Furukawa, was involved throughout this process as the Chief Representative, JICA South Sudan Office. The book records the struggle of one Japanese person, along with a great many South Sudanese people, who held out the hope of realizing Peace and Unity in a country that had seen more than 50 years of conflict, both before and after its independence. -

Youth and Therapeutic Insurgency in Eastern Congo: an Ethnographic History of Ruga-Ruga, Simba, and Mai-Mai Movements, 1870 - Present

Youth and Therapeutic Insurgency in Eastern Congo: An Ethnographic History of Ruga-Ruga, Simba, and Mai-Mai Movements, 1870 - Present by Jonathan Edwards Shaw A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Nancy Rose Hunt, Co-chair Professor Derek Peterson, Co-Chair Professor Adam Ashforth Professor Mike McGovern Professor Koen Vlassenroot, Ghent University Jonathan Edwards Shaw [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6337-434X © Jonathan Edwards Shaw 2018 2 Dedication For my sons. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation, whatever its weaknesses, is the product of significant labor, sacrifice, and commitment from many individual people and organizations. My field research would not have been possible without support from the Social Science Research Council’s Mellon International Dissertation Research Fellowship program. I particularly wish to thank Daniella Sarnoff for her support and encouragement. Field research was also funded by the United States Institute for Peace’s Jennings Randolph Fellowship program. Lili Cole proved an unstintingly supportive and flexible ally there. I am grateful to the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for awarding me both a Humanities Fellowship as well as an International Research Fellowship. I thank Diana Denney and Kathleen King within the History Department at the University of Michigan for their aid in applying for those opportunities and for many other tangible and intangible forms of support during my career as a graduate student. I am thankful to have received an African Initiatives Grant from the African Studies Center and Department of African and Afro-american Studies at the University of Michigan, with particular gratitude to Anne Pitcher in that program. -

Exploring the Caregiver-Child Relationship in Institutional Care Facilities in South Sudan

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Summer 2017 Exploring the Caregiver-Child Relationship in Institutional Care Facilities in South Sudan Jennifer Joy Telfer Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the African Studies Commons, Anthropology Commons, Child Psychology Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Telfer, Jennifer Joy, "Exploring the Caregiver-Child Relationship in Institutional Care Facilities in South Sudan" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3140. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3140 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected].