Richard Davidson Biography from Current Biography (2004) Copyright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness and the 12 Steps

mindfulness and the 12 steps with Thérèse Jacobs-Stewart Resting the Mind • Assume a body position where your spine is straight and your body relaxed. • Allow your mind to rest for a few minutes, letting whatever happens-or doesn’t happen-be a part of the experiment. • Relax with whatever arises. • When time is up, ask yourself, “How was that?” (Don’t judge; just review what happened and how you felt.) • The only difference between meditation and the ordinary process of feeling, thinking, feeling, and sensation is the application of the “bare awareness.” Mindfulness Meditation Consciously bring awareness to your here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and self-acceptance. 1 Ways Mindfulness and Meditation Help the Therapist • Offers idea of “strengthening the heart” vs. western psychology’s concept of “self-care.” • Reduces compassion fatigue, renews energy, and counteracts burn-out. • Deepens capacity for a compassionate and non- judging presence. • Increases ability to abide with difficult emotions, offering hope and relief. • Sharpens awareness of therapist’s own reactions. Specific Brain States Correlate with Happiness Brain Activity Associated with Mindfulness Meditation 2 Meditation Changes the Circuitry of the Brain Jacobs-Stewart, Paths Are Made by Walking, 2003 “Meditation training can change the brain and forever alter our sense of well-being.” Richard Davidson Laboratory for Neuroaffective Science University of Wisconsin, Madison 3 Effects of Mindfulness on the Addictive Brain • Enhances neural plasticity. • Reduces activity in the amygdala. • Thickens the bilateral, prefrontal right-insular region of the brain. • Integrates prefrontal regulation and limbic emotion activation. • Builds new neural connections among brain cells for self-observation, optimism, and well-being. -

Reviewers Who Completed a Review During 2001

REVIEWERS LIST The constituency of the ARCHIVES comprises a “university” of often interchangeable writers and readers, students, knowledgeable practitioners, and scholars of medicine and sciences underlying the field of psychiatry. The editors are deeply grateful to the many colleagues listed here for their generous assistance in editorial critique and review. The donation of their special expertise is a necessary contribution on which the intellectual standards in the field heavily depend. Jack D. Barchas, MD Editor Larry Abel Francesc Artigas Chawki Benkelfat Evelyn Bromet James Abelson Robert Asarnow Lisa Berkman Judith S. Brook Anissa Abi-Dargham Wesson Ashford Karen Faith Berman Robert K. Brooner Howard B. Abikoff Boris Astrachan Robert Berman George W. Brown Lyn Y. Abramson Evelyn Attia Greg Berns Marty Bruce T. M. Achenbach S. Avenevoli Wade Berrettini Gerard E. Bruder Kenneth M. Adams Elizabeth Auchincloss Larry E. Beutler Maja Bucan Lawrence E.Adler David Avery Joseph Biederman Robert W. Buchanan Lenard A. Adler Thomas Babor Laura Bierut Kathleen K. Bucholz Nancy E. Adler Nadia Badawi George Bigelow Monte Buchsbaum Ralph Adolphs Alan D. Baddeley Robert Bilder Alan J. Budney George Aghajanian Lee Baer Rene Binder Stephen L. Buka W. Stewart Agras J. Michael Bailey Ray Bingham William E. Bunney Schahram Akbarian Ross J. Baldessarini Niels Birbaumer Audrey Burnam Huda Akil James C. Ballenger Boris Birmaher Barbara J. Burns Hagop S. Akiskal J. Bancroft Donald Black Terry Bush Claude Alain Karen J. Bandeen-Roche D. H. Blackwood Daniel Buysse Marigarita Alegria Deanna M. Barch Jack Blaine William Byne Georgios Alexopoulos John C. Barefoot Helen Blair Simpson Robert P. Cabaj Kimmo Alho Russell A. -

Toward the Integration of Meditation Into Higher Education: a Review of Research

Toward the Integration of Meditation into Higher Education: A Review of Research Prepared for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society by Shauna L. Shapiro Santa Clara University Kirk Warren Brown Virginia Commonwealth University John A. Astin California Pacific Medical Center Supplemental research and editing: Maia Duerr, Five Directions Consulting October 2008 2 Abstract There is growing interest in the integration of meditation into higher education (Bush, 2006). This paper reviews empirical evidence related to the use of meditation to facilitate the achievement of traditional educational goals, to help support student mental health under academic stress, and to enhance education of the “whole person.” Drawing on four decades of research conducted with two primary forms of meditation, we demonstrate how these practices may help to foster important cognitive skills of attention and information processing, as well as help to build stress resilience and adaptive interpersonal capacities. This paper also offers directions for future research, highlighting the importance of theory-based investigations, increased methodological rigor, expansion of the scope of education-related outcomes studied, and the study of best practices for teaching meditation in educational settings. 3 Meditation and Higher Education: Key Research Findings Cognitive and Academic Performance • Mindfulness meditation may improve ability to maintain preparedness and orient attention. • Mindfulness meditation may improve ability to process information quickly and accurately. • Concentration-based meditation, practiced over a long-term, may have a positive impact on academic achievement. Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being • Mindfulness meditation may decrease stress, anxiety, and depression. • Mindfulness meditation supports better regulation of emotional reactions and the cultivation of positive psychological states. -

Mindfulness and Emotional Intelligence Principles and Practices To

6 Mindfulness and Emotional Intelligence Principles and Practices to Corwin Transform Your Leadership Life “[T]here is a limit to the role of the intelligence in human Copyright affairs.” —James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son (1955)1 A Leader Fails to Notice Jonathan, a 52-year-old chief academic officer (CAO) of a large subur- ban district in California, is a scholar. Not only does he work tirelessly planning professional learning in his district; he also finds time to write several articles for professional trade publications and has authored a chapter in a well-received book on new forms of teacher evaluation from an administrator’s point of view. Recently promoted, he has asked us to observe him during a senior staff meeting to help him with some “communication fine-tuning.” We happily agree. After some preliminaries and a couple of agenda items are announced, we observe Jonathan talk for almost 12 minutes about his goals as a 157 158 The Mindful School Leader new CAO, the latest district strategic planning session, and the books he is reading. He appears not to observe the body language of others in the room, and sometimes seems only distantly aware of their pres- ence. Finally, he turns to his executive staff to ask whether anyone has anything to contribute to the “discussion,” yet before anyone can reply, he shifts into another discourse about the iPad policy at one of the district’s schools. His colleagues begin to give each other side glances, adjust their clothing and hair, move about in their seats, and reach for their phones but Jonathan doesn’t seem to notice. -

An Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION

Thought Without Language: an Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Dean Jaworski Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Neil Tennant, Advisor William Taschek Ben Caplan Copyright by Michael Dean Jaworski 2010 Abstract I defend an account of thought on which non-linguistic beings can be thinkers. This result is significant in that many philosophers have claimed that the ability to think depends on the ability to use language. These opponents of my view note that our everyday understanding of our own cognitive activities qua thought bestows upon those activities the propositional structure of sentences and the inferential norms of public linguistic practice. They hold that our attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings project non-existent structure onto the cognitive activities of those beings, and assess the beings’ activities according to standards to which the beings bear no responsibility. So, despite the complex neural and behavioral activities of many non-linguistic beings, my opponents hold that those beings are not properly described as thinkers. To respond to my opponents successfully, one must not merely cite scientific and folk practices of thought attribution that permit thought to be attributed to some non- linguistic beings. My opponents’ insights might be taken to demonstrate a need to revise those practices, or to treat the attributions of thought to non-linguistic beings made within those practices as instrumentally valuable but technically false. Instead, my strategy is to acknowledge the language-like structure and norms of thought, and show that a non- linguistic being’s cognitive activities might nonetheless have that structure and be subject ii to those norms. -

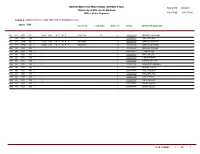

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM SUBJECT: AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMICS (108) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME AGRICULTURALALS AND APPLIED ECONOMICS ACC 306 LEC 001 1 09:00 - 12:00 M T W R 0140 1185 49 6 0000875079 MICHAEL JOHNSON DJJ 399 IND 086 1 - 2 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL ECC 875 SEM 001 2 13:00 - 16:00 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON ECC 875 SEM 001 1 08:30 - 11:30 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON DHH 990 IND 063 1 - 9 0000226384 MICHAEL CARTER DHH 990 IND 064 1 - 1 0002600175 THOMAS COX DHH 990 IND 073 1 - 3 0002601457 IAN COXHEAD DHH 990 IND 078 1 - 3 0002602152 T FORTENBERY DHH 990 IND 079 1 - 1 0002600972 STEVEN DELLER DHH 990 IND 080 1 - 3 0002602096 BRADFORD BARHAM DHH 990 IND 082 1 - 2 0000125075 JEREMY FOLTZ DHH 990 IND 083 1 - 6 0003374884 KYLE STIEGERT DHH 990 IND 086 1 - 1 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL DHH 990 IND 087 1 - 3 0004111956 DAVID LEWIS DHH 990 IND 089 1 - 1 0001459007 SHI GUANMING DHH 990 IND 090 1 - 1 0001016452 BRENT HUETH DHH 999 IND 085 1 - 1 0003088634 BRIAN GOULD PAGE NUMBER: 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:44:48AM SUBJECT: BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING (112) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING DHH 399 IND 010 1 - 2 0000693634 DAVID BOHNHOFF DHH 399 IND 014 1 - 2 0000664097 -

The Buddha on Meditation and Higher States of Consciousness

The Buddha on Meditation and Higher States of Consciousness By Daniel Goleman Harvard University Buddhist Publication Society Kandy • Sri Lanka The Wheel Publication Nos. 189/190 Reprinted by permission of the Transpersonal Institute, 2637 Marshall Drive, Palo Alto, California 94303 U. S. A. First reprint—1973 Second reprint—1980 BPS Online Edition © (2008) 2 Digital Transcription Source: BPS Transcription Project For free distribution. This work may be republished, reformatted, reprinted and redistributed in any medium. However, any such republication and redistribution is to be made available to the public on a free and unrestricted basis, and translations and other derivative works are to be clearly marked as such. 3 The Buddha on Meditation and Higher States of Consciousness [1] In the Buddhist doctrine, mind is the starting point, the focal point, and also, as the liberated and purified mind of the Saint, the culminating point. Nyanāponika, Heart of Buddhist Meditation Introduction he predicament of Westerners setting out to explore T those states of consciousness discontinuous with the normal is like that of the early sixteenth century European cartographers who pieced together maps from explorers’ reports of the New World they had not themselves seen. Just as Pizarro’s report of the New World would have emphasized Peru and South America and underplayed North America, while Hudson’s would be biased toward Canada and North America to the detriment 4 of South America, so with explorers in psychic space: each report of states of consciousness is a unique configuration specific to the experiences of the voyager who sets it down. That the reports overlap and agree makes us more sure that the terrain within has its own topography, independent of and reflected in the mapping of it. -

Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2018 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness Peter H. Huang University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Citation Information Peter H. Huang, Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness, 7 BRIT. J. AM. LEGAL STUD. 425 (2018), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1237. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 7(2) (2018), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2018-0008 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, And Mindfulness Peter H. Huang* ABSTRACT Spis treści This Article recounts my unique adventures in higher education, including being a Princeton University freshman mathematics major at age 14, Harvard University applied mathematics graduate student at age 17, economics and finance faculty at multiple schools, first-year law student at the University of Chicago, second- and third-year law student at Stanford University, and law faculty at multiple schools. -

Essentials of Presence & Mindfulness Vipassana

Practical Mindfulness | Online Study Program Module 1: Essentials of Presence & Mindfulness “Wherever you are, is the entry point.” – Kabir Lesson 2, Item 2.2 | THE SOURCE Vipassana Meditation VIPASSANA MEDITATION has proved to be an important and common thread in the The basic course is a ten-day silent retreat where you meditate for twelve hours a day, development of mindfulness. It was an important early source of both Jon Kabat-Zinn’s sitting for two hours at a time. You start by observing the sensations of your body in a and Daniel Goleman’s work. I myself learned and practised it too, and that led me to the very focused area and your job is to keep bringing your mind back to observing those creation of my own mindfulness program before I knew about this common thread. sensations with no judgement, no reaction. By day four you have to sit through an hour Therefore, let’s take a quick look at it. without moving or fidgeting, while scanning your whole body with no judgement, no The modern teachers of Vipassana claim that this is the meditation developed and reaction. Thereafter, sitting without moving or fidgeting throughout the sessions practised by Gautama the Buddha when he sat under the Bodhi tree to achieve becomes the standard requirement and an essential part of the training. enlightenment. At the very least, it has an ancient history and comes from the Buddhist When you complete the course, it is recommended that you sit twice a day, morning Theravadan tradition. A lineage of masters in Burma have passed it on over centuries, and evening, for an hour each time. -

Npp2013281.Pdf

Neuropsychopharmacology (2013) 38, S435–S593 & 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/13 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session III-Wednesday participants indicated their ongoing experience of the Wednesday, December 11, 2013 intensity of heartbeat and breathing sensations by rotating a dial. Discrimination was measured by a positive dial deflection above baseline during an infusion trial. Accuracy W2. Interoceptive Awareness in Meditators During was measured via maximum cross correlation between each Cardiorespiratory Deviations in Body Arousal subject’s dial ratings and their corresponding heart rate Sahib Khalsa*, David Rudrauf, Richard Davidson, response. After each infusion participants also traced the Daniel Tranel body locations where they had felt heartbeat sensations, on a manikin template. UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Results: Bolus isoproterenol infusions elicited equivalent Behavior, Los Angeles, California increases in heart rate in both groups (Repeated measures ANOVA; F(1, 5) ¼ 50.1, po0.0001). There were no signifi- Background: Attention directed towards internal body cant group (F(1, 28) ¼ 1.27, p ¼ 0.27) or group x dose sensations is commonly practiced in many meditation interactions (F(1, 5) ¼ 0.04, p ¼ 0.998). There were also no traditions, and is a core skill cultivated when learning group differences in adrenergic sensitivity as measured by mindfulness. This practice is commonly proposed to CD25 (dose required to elevate heart rate by 25 beats per -

Willis and the Virtuosi

Forum on Public Policy The Scientific Method through the Lens of Neuroscience; From Willis to Broad J. Lanier Burns, Professor, Research Professor of Theological Studies, Senior Professor of Systematic Theology, Dallas Theological Seminar Abstract: In an age of unprecedented scientific achievement, I argue that the neurosciences are poised to transform our perceptions about life on earth, and that collaboration is needed to exploit a vast body of knowledge for humanity’s benefit. The scientific method distinguishes science from the humanities and religion. It has evolved into a professional, specialized culture with a common language that has synthesized technological forces into an incomparable era in terms of power and potential to address persistent problems of life on earth. When Willis of Oxford initiated modern experimentation, ecclesial authorities held intellectuals accountable to traditional canons of belief. In our secularized age, science has ascended to dominance with its contributions to progress in virtually every field. I will develop this transition in three parts. First, modern experimentation on the brain emerged with Thomas Willis in the 17th Century. A conscientious Anglican, he postulated a “corporeal soul,” so that he could pursue cranial research. He belonged to a gifted circle of scientifically minded scholars, the Virtuosi, who assisted him with his Cerebri anatome. He coined a number of neurological terms, moved research from the traditional humoral theory to a structural emphasis, and has been remembered for the arterial structure at the base of the brain, the “Circle of Willis.” Second, the scientific method is briefly described as a foundation for understanding its development in neuroscience. -

Official Press Kit

OFFICIAL PRESS KIT Contents ABOUT THE FILM………………………………………………………………..………..Page 2‐4 DIRECTOR BIO………………………………………………………………………………Page 5 WADI RUM FILMS ABOUT…………………………………………………………….Page 6 PHOTO PAGE………………………………………………………………………………..Page 7 FACES OF HAPPY…………………………………………………………………………..Page 8‐9 www.TheHappyMovie.com ABOUT THE FILM From the Academy Award® nominated director Roko Belic (Genghis Blues) comes a new cinematic adventure. HAPPY is a feature‐length documentary that leads viewers on a journey across 5 continents in search of the keys to happiness. The film addresses many of the fundamental issues we face in today’s society: how do we balance the allure of money, fame and social status with our needs for strong relationships, health and personal fulfillment? Through remarkable human stories and cutting‐edge science, HAPPY leads us toward a deeper understanding of why and how we can pursue more fulfilling, healthier and happier lives. HAPPY takes the viewer from the bayous of Louisiana to the deserts of Namibia, from the beaches of Brazil to the mountains of Bhutan. Listen to the wisdom of a Kolkata rickshaw driver, the compassion of a volunteer at Mother Teresa’s Home for the Dying and the knowledge of some of the world’s leading happiness researchers. Witness as middle school students applaud the bravery of their classmates during a moving presentation on bullying. HAPPY combines real‐life human drama and cutting‐edge science to provide insights into the mysteries of happiness. In 2005, director Tom Shadyac (Liar Liar, Patch Adams, Bruce Almighty) handed Roko Belic a New York Times article entitled, “A New Measure of Well‐Being From a Happy Little Kingdom.” The article ranked the United States 23rd on its list of happiest countries.