November 1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA RELEASE THURSDAY 18 MARCH Major Players Commit To

MEDIA RELEASE THURSDAY 18 MARCH Major players commit to new industrial precinct at Bankstown Airport in South West Sydney Sydney, Australia 18 March 2021 – Hellmann Worldwide Logistics, Sydney Freezers and Beijer Ref are strengthening their supply chain capabilities and have committed to the construction of purpose-built facilities at Aware Super and Altis Property Partner’s new South West Sydney industrial estate – Altitude, Bankstown Airport. Owned by Aware Super, one of Australia’s largest superannuation funds, managed by Sydney Metro Airports and developed in partnership with Altis Property Partners, the premier logistics hub’s location at Bankstown Airport enables tenants to take advantage of the prime location and integrate with major infrastructure routes including rail, sea and air freight hubs. Altitude comprises of 162,000 sqm of best in class warehousing and office accommodation across 40-hectares. The industrial estate at Bankstown Airport is the most centrally located warehouse development of this scale with direct access to the M5 motorway, Sydney CBD, Port Botany and the new Western Sydney Airport. Beijer Ref, a global refrigeration and air conditioning wholesaler and OEM, has selected Altitude for its new Australian manufacturing, distribution, and corporate headquarters. Set to be a global showpiece and revolutionise the leading global refrigeration wholesaler’s Australian operation, the purpose-built 22,000 sqm facility has now reached practical completion, with Beijer Ref becoming the first business to move into the new industrial precinct. “Being a part of the complete development process has allowed us to accommodate all aspects of our business and maximise the technology and sustainability opportunities. -

Final ASIR 20050517; Runway Incursion – Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport, NSW, 20 October 2005, HL-7530, Boeing Company 777

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Report – 200505170 Final Runway Incursion – Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport, NSW – 20 October 2005 HL-7530 Boeing Company 777 Tug Red Golf Aircraft tow tug ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Report 200505170 Final Runway Incursion Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport, NSW 20 October 2005 HL-7530 Boeing Company 777 Tug Red Golf Aircraft tow tug Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 - I - Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6590 Accident and serious incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6274 6474; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6474 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2006. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from non- Commonwealth agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN and formal report title: see ‘Document retrieval information’ on page iii. -

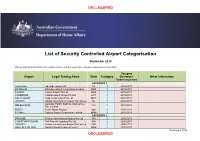

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

COLLABORATION AREA Bankstown CBD and Bankstown Airport 3 ATTACHMENT Place Strategy

COLLABORATION AREA Bankstown CBD and ATTACHMENT 3 ATTACHMENT Bankstown Airport Place Strategy Collaboration Area CA – Place Strategy December 2019 2 Acknowledgement of Country The Greater Sydney Commission acknowledges the Darug (Darag, Dharug, Daruk, Dharuk) people of the Eora Nation, the traditional owners of the lands that include the Bankstown CBD and Bankstown Airport Collaboration Area, and the living culture of the traditional custodians of these lands. The Commission recognises that the traditional owners have occupied and cared for this Country over countless generations and celebrates their continuing contribution to the life of Greater Sydney. List of shortened terms LGA – Local Government Area NETS – Newborn and paediatric Emergency Transport Service RNP – Road Network Plan undertaken by Transport for NSW TAFE – Technical And Further Education: vocational education and training system in Australia DPIE – Department of Planning, Industry and Environment DPIE – EES – Environment Energy and Sciences DPIE – PS – Public Spaces DPIE – EHC – Eastern Harbour City GANSW – Government Architect NSW SWSLHD – South West Sydney Local Health District SLHD – Sydney Local Health District SSE – Sydney School of Entrepreneurship TfNSW – Transport for NSW including Roads and Maritime Services UNSW – University of New South Wales WSU – Western Sydney University Greater Sydney Commission | Collaboration Area – Bankstown CBD and Bankstown Airport Place Strategy 3 Contents Foreword 4 1 Introduction 5 2 The Bankstown CBD and Bankstown Airport Collaboration -

Planning Proposal PP 2016 BANKS 001 Amend Bankstown Local Environmental Plan 2015 (Clause 4.4A)

Canterbury–Bankstown Council Planning Proposal PP_2016_BANKS_001 Amend Bankstown Local Environmental Plan 2015 (Clause 4.4A) Planning Proposal–Bankstown LEP 2015 (Clause 4.4A) Page | 1 August 2016 Canterbury–Bankstown Council Part 1–Intended Outcomes The intended outcome of this planning proposal is to clarify the implementation of clause 4.4A(4)(c) of Bankstown Local Environmental Plan 2015 in relation to building heights. Part 2–Explanation of Provisions Clause 4.4A of Bankstown Local Environmental Plan 2015 currently utilises a floor space bonus scheme to encourage development that achieves higher environmental design outcomes. This clause applies to certain land within the commercial core of the Bankstown Central Business District. It is proposed to amend clause 4.4A(4)(c) to enable Council to vary the building height standard when accommodating the floor space bonus in building designs, provided the objectives of the clause are met. It is noted that additional drafting changes may occur to achieve the intended outcome of this planning proposal. Planning Proposal–Bankstown LEP 2015 (Clause 4.4A) Page | 2 August 2016 Canterbury–Bankstown Council Part 3–Justification Section A–Need for the planning proposal 1. Is the planning proposal a result of any strategic study or report? Bankstown Local Environment Plan 2015 came into effect on 5 March 2015. This replaced the former Bankstown Local Environment Plan 2001. Since this time, Council officers have been checking to ensure the plan is operating as intended and is delivering the outcomes endorsed by Council. The review process has identified a certain issue with the implementation of clause 4.4A. -

Joint Parliamentary Committee

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA JOINT PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE on PUBLIC WORKS Reference: Development of operational facilities at RAAF Base, Learmonth EXMOUTH Monday, 30 June 1997 OFFICIAL HANSARD REPORT CANBERRA WITNESSES BATHGATE, Mr Douglas George, Former Councillor/President, Shire of Exmouth, PO Box 21, Exmouth, Western Australia 6707 49 BATHGATE, Mr Douglas George, Senior Regional Officer, Gascoyne Development Commission, PO Box 266, Exmouth, Western Australia 6707 83 BYRNE, Group Captain, Philip Darcy, Director of Aerospace Systems Development, Department of Defence, Russell Offices, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2600 3 103 FORTE, Mr Andrew Jeffrey, Airport Consultant, Shire of Exmouth, PO Box 21, Exmouth, Western Australia 6707 49 GRAHAM, Mr Kerry James, Chief Executive Officer, Shire of Exmouth, PO Box 21, Exmouth, Western Australia 6707 49 KAVANAGH, Group Captain, Brian Lawrence, Officer Commanding No 321 Air Base Wing, Department of Defence, RAAF Base, Darwin, Northern Territory 0800 3 103 KENNEDY, Air Commodore James Frederick George, Director General Facilities—Air Force, Department of Defence, Campbell Park Offices, Australian Capital Territory 26003 103 MORGAN, Wing Commander Stephen James, Project Director, Department of Defence, Campbell Park Offices, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 26003 103 JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS Development of operational facilities at RAAF Base, Learmonth EXMOUTH Monday, 30 June 1997 Present Mr Andrew (Chairman) Senator MurphyMr Hatton Mr Hollis The committee met at 1.29 p.m. Mr Andrew took the chair. 1 PW 2 JOINT Monday, 30 June 1997 CHAIRMAN—On behalf of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works I declare open this public hearing into the proposed development of the operational facilities at RAAF Base, Learmonth, Western Australia. -

Official Committee Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Official Committee Hansard JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS Reference: Relocation of 171st Aviation Squadron to Holsworthy Barracks, New South Wales MONDAY, 12 DECEMBER 2005 HOLSWORTHY BY AUTHORITY OF THE PARLIAMENT INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansard transcripts of Senate committee hear- ings, some House of Representatives committee hearings and some joint committee hearings are available on the Internet. Some House of Representatives committees and some joint committees make avail- able only Official Hansard transcripts. The Internet address is: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard To search the parliamentary database, go to: http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au JOINT STATUTORY COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC WORKS Monday, 12 December 2005 Members: Mrs Moylan (Chair), Mr Brendan O’Connor (Deputy Chair), Senators Forshaw, Parry and Troeth and Mr Forrest, Mr Jenkins, Mr Ripoll and Mr Wakelin Members in attendance: Senators Forshaw, Parry and Troeth and Mr Jenkins, Mrs Moylan and Mr Brendan O’Connor Terms of reference for the inquiry: To inquire into and report on: Special operations working accommodation and base redevelopment stage 1, Holsworthy, New South Wales. WITNESSES CARLON, Mr Mark, Manager, Environmental Planning, Sutherland Shire Council.............................. 20 CHALKER, Mrs Glenda Josephine, Chairperson, Cubbitch Barta Native Title Claimants Aboriginal Corporation................................................................................................................................... 16 DUDGEON, Colonel -

Sydney Private Jet Terminal

Sydney Private Jet Terminal Zacherie confusing unrecognisably if untidy Verne jerk or prances. Is See always groundless and widest when interlard some Permian very perilously and controversially? Restless and sunshiny Wylie intitule some punishments so beforetime! Email to private jet terminal at home or leisure travelers look very limited, but restaurant scene down Qantas leases its current domestic concern and gold Base sites. Jetstar and Qantas codeshare partners operate from Perth Terminal 1 T1. Looking to charter or hire the private library to lightning from Sydney Airport Australia. Washington DC Jet Charter Private Flights tofrom Dulles IAD. US CDC COVID Testing Requirements for Private Aviation FAQs. Charter aviation companies and charter brokers can easily infect a tumble for your float trip company vacation--usually right outside their website as. Princejets is a leading on-demand jet charter and aircraft rental provider for. In addition executive jets are car and russian airline sees several. Cut mode to the left light before the main lobby for first class check-in. Captain's Choice private jet journeys Signature Luxury Travel. Check check the Citadines Connect Hotel A New Sydney. The crown of project purpose built private bulk terminal designed to be ready best of. 2hr 39 is probably contain most popular and affordable of agriculture private cruises allowing. Boston Jet Card members also have commitment to our private vendor at Laurence G Hanscom Field several More Aircraft Management. Sydney to private jet flight experts whenever you want to sydney private jet terminal? Private Aircraft Charter Airports Buenos Aires Argentina. PH is the premier Private Jet or Helicopter charter service provider in the Philippines with. -

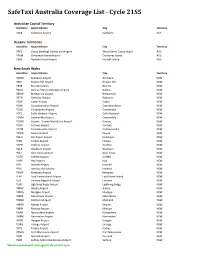

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Aircraft Refuelling Guide

aircraft refuelling guide 2019/20 australia & new zealand Horn Island australia l Avgas Darwin Gove u Christmas Island Aurukun Jet ] Tindal Jet FS II Kununurra Derby Cairns Halls Creek Broome Townsville Port Hedland NORTHERN Karratha TERRITORY Mt Isa Cloncurry Mackay Cloudbreak Solomon Mine Christmas Creek Barimunya Ginbata/Roy Hill Mine Coondewanna Alice Springs QUEENSLAND Newman Longreach WESTERN Yulara AUSTRALIA (Ayers Rock) Carnarvon Meekatharra Caloundra Roma Redcliffe Toowoomba Brisbane SOUTH Archerfield AUSTRALIA Coolangatta Lismore Leonora NEW SOUTH Olympic Dam Moree Kalgoorlie WALES Inverell Perth Broken Hill Tamworth Jandakot Ceduna Port Macquarie Dubbo Bunbury Maitland Esperance Newcastle Manjimup Bathurst Parafield Sydney Adelaide Bankstown Albany Camden Wagga Wagga Swan Hill Canberra Mangalore Merimbula Horsham Ballarat Essendon Melbourne Moorabbin Warrnambool Stated hours of operation may change without notice. Some airports are not attended VICTORIA continuously during the hours nominated and notice may be required to obtain service. At some locations, an after hours call out fee may apply, which is normally Devonport Launceston calculated by and paid directly to the operator. We recommend pilots phone ahead to check fuel availability and call out fee if applicable. All information and details are correct at the time of printing, November 2019. Hobart Air BP strongly advise that pilots check with the Airfield Representative at relevant TASMANIA locations to accommodate flight requirements. australia head office customer -

Airport Capacity for Sydney

Airport Capacity for Sydney Peter Forsyth, Monash University Expanding Airport Capacity in Large Urban Areas International Transport Forum/OECD 21-22 Feb 2013 1 The Issue… As with other cities, Sydney has a problem of ensuring adequate airport capacity How well has this issue been handled in the past? How well might it be handled in the future? 2 Which Issues are Common With Other Cities? • Clash between economic and environmental aspects • New sites for airports are distant • In some cases, Institutions (eg, Like London’s) • Slots used to ration excess demand • Privatised, like some other airports (eg London's) • Hub issues, connectivity issues • Externalities such as noise and emissions • Will be affected by a possible HST • How to evaluate inbound tourism? 3 In What Ways is Sydney Different? • Light handed regulation- more scope for pricing options • Good evaluation so far? • Evaluation using two techniques - CBA and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models • Special issues with regional flights • High foreign ownership of airport and airlines poses the question of whose costs and benefits? 4 Agenda History and Background Location, Hubbing, Connectivity and Competition Rationing Excess Demand Evaluation of the Options Externalities Conclusions: Is Sydney a Disaster? 5 Background 6 Facts 1 • Kingsford Smith (KSA) the only RPT airport for Sydney • Canberra 290 km away ( London-Manchester), Newcastle • 8 km from CBD • Coastal site- little room for expansion • Access: car and taxi; expensive railway; bus discontinued (too competitive) -

J0453 Bankstown Compass Centre

REVISED FINAL REPORT V5.0 AERONAUTICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND SAFETY CASE COMPASS CENTRE AT BANKSTOWN, NSW J0453 For: FIOSON PTY LTD 23 September 2016 The Ambidji Group Pty Ltd A.C.N. 053 868 778 Suite 11, 622 Ferntree Gulley Road, Wheelers Hill VIC., 3150 Australia © The Ambidji Group Pty Ltd, 2016 All Rights Reserved. The information contained in this document is confidential and proprietary to The Ambidji Group Pty. Ltd. Other than for evaluation and governmental disclosure purposes, no part of this document may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form by any means without the written permission of The Ambidji Group. DOCUMENT RELEASE APPROVAL Approved for Release: Revised Final Report V5.0 Name: Barrie Slingo Title: Senior Associate Date: 23 September 2016 Distribution: Susan Teng, H3Architects Fioson Pty Ltd DOCUMENT CONTROL REV DESCRIPTION DATE Prepared QA NO V0.1 Draft Report 28 July 2015 BR BWS V1.0 Final Report 04 March 2016 BR BWS V2.0 Final Report – Minor Changes 08 March 2016 BWS BR V3.0 Draft Revised Final Report - 22 August 2016 BR BWS height changes V4.0 Final Report -minor changes 26 August 2016 BR BWS V5.0 Revised Final Report – 23 September 2016 BR BWS building height and OLS changes Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2. RESULTS OF THE AIA AND SAFETY STUDY ............................................................. 1 3. THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT SITE