A Sociological Study of Aligarh City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

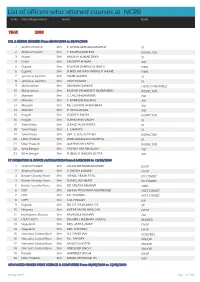

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

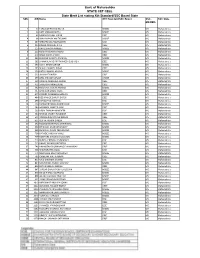

Govt. of Maharashtra STATE CET CELL State Merit List Stating Xth Standard/SSC Board State SML AIR Name XTH Standard/SSC Board SSC- SSC State MS/OMS

Govt. of Maharashtra STATE CET CELL State Merit List stating Xth Standard/SSC Board State SML AIR Name XTH Standard/SSC Board SSC- SSC State MS/OMS 1 33 HERLEKAR RUCHA RAHUL MSBSE MS Maharashtra 2 66 KATE VIKRAM RAJESH MSBSE MS Maharashtra 3 82 MANN RUSSAAL SINGH CBSE MS Maharashtra 4 96 SHAH MANAV AMITKUMAR MSBSE MS Maharashtra 5 147 SHROTRI GAUTAM RAJESH ICSE MS Maharashtra 6 149 KABRA AANCHAL ATUL CBSE MS Maharashtra 7 214 PATIL SHARVA RANJEET MSBSE MS Maharashtra 8 250 MANTRI AKASH SHARAD CBSE MS Maharashtra 9 279 KINGE SARAS VINOD CBSE MS Maharashtra 10 282 BARGAJE SHWETA PRAKASH MSBSE MS Maharashtra 11 285 SAWWALAKHE PRATHAMESH SUBHASH CBSE MS Maharashtra 12 293 SAIKH IRFAN SARVAR MSBSE MS Maharashtra 13 295 SHAIKH SHARZIL NISAR CBSE MS Maharashtra 14 303 PATIL YASHRAJ ARVIND MSBSE MS Maharashtra 15 323 JAIN ADIT RAJESH CBSE MS Maharashtra 16 359 ATAL SHIVAM SANJAY MSBSE MS Maharashtra 17 380 UKARDE ABHISHEK ANAND CBSE MS Maharashtra 18 433 SANGTANI NIKHIL SUNIL CBSE MS Maharashtra 19 442 MACHAVE AMEYA PRASAD MSBSE MS Maharashtra 20 447 GHOTKAR MINAL VILAS CBSE MS Maharashtra 21 477 KENDRE RUSHIKESH MOHAN MSBSE MS Maharashtra 22 484 DESHPANDE SHRUTI SATISH CBSE MS Maharashtra 23 490 GOYAL RIYA HANSRAJ ICSE MS Maharashtra 24 504 KABRA PRIYANKA RAMKISHAN MSBSE MS Maharashtra 25 544 AGRAWAL ABHEER SUNIL CBSE MS Maharashtra 26 563 DESAI TWARAA MANDEEP ICSE MS Maharashtra 27 564 SHUKLA SHUBHI RAVIKANT CBSE MS Maharashtra 28 611 VINCHURKAR PIYUSH MANOJ CBSE MS Maharashtra 29 631 GUPTA TANIKA DINESH ICSE MS Maharashtra 30 642 MUDGERIKAR -

Electronics.Pdf

1983 Bhoite Sanjay Lxminagar,Phaltan,Dist.Satara 1983 electronic Bhujbal Vilas 941,Bhavani peth,Pune 2 1983 electronic Choudhary sunil 1983 electronic Desai Ojas 1983 electronic Desai Manish 1983 electronic Desai Ranjeet 1983 electronic Dhameja Sandip 2,IAT,girinagar,Pune 25 1983 electronic Dhand Kailash Century enka col,Bhosari,Pune 26 1983 electronic Dharap Sujata 1983 electronic Deshpande S.V 1983 electronic Dhekane Shrikant Mahatma soc,Karve nagar,Pune29 1983 electronic Delima John 68,dastur meher rd,Pune 1 1983 electronic Dobhada Sachin Yashvant nagar,Akluj,dist.Solapur 1983 electronic D’souza Salvador 1983 electronic Erande rajan 76/16,shantishila soc,erandavane,Pune4 1983 electronic Fernandez Alvile 1983 electronic GajendragadkarA.M 1983 electronic Gandhi Sadanand 1983 electronic Ghare Achut 764,sadashiv peth,Pune 30 1983 electronic Godbole Jitendra 1983 electronic Ghatge Prithviraj 1983 electronic Ghole Nitin 1983 electronic Jitentra Ghosalkar 1983 electronic Sameer Gogate 1983 electronic Goverdhan 1983 electronic subodh Nandan gumaste 1983 electronic Iyer Sridhar 1983 electronic Hajare 1983 electronic Sanjaykum Gupta sunil 1983 electronic Jagtap 1983 electronic krishnakant Joshi abhay D-61-4 ,Range hills,Pune3 1983 electronic Kadakia Harshal 99 A,Huges Rd,Mumbai 36 1983 electronic Kale Makrand 1983 electronic Kale Sandip 624/9 Indira,shanwar peth Pune 30 1983 electronic Kasnoria Tirandar 1983 electronic Kela sanjeev 1983 electronic Ketkar ruta 992, ,Navi peth,Pune 30 1983 electronic Khan Nasib nwar 1983 electronic Karandikar 1983 electronic milind Khurram Ahmad 1983 electronic Kulkarni Deepa 1983 electronic Kulkarni basindra Indira app, shila ihar col,Pune 38 1983 electronic Kulkarni jayant 1983 electronic Kulkarni N.V Vijaynagar col,Pune 30 1983 electronic Kulkarni N.S. -

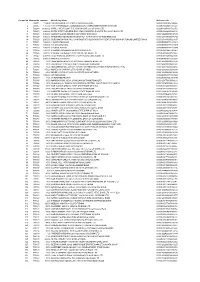

60001 to 70000 MHT-CET 2005 State Level Merit List

Government of Maharashtra Page : 1 SML Range : 60001 To 70000 MHT-CET 2005 State Level Merit List ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SML No Cat Reg Roll Name Phy Che Bio Addl PCB SSC % Sp Reservation ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 60001 1 1206050 GAIKWAD REKHA B 12 18 48 78 78.00 60002 SC 2 4300197 JANBANDHU MAHESHWARI S 12 18 48 78 77.33 60003 1 1100740 NAVED F 12 18 48 78 75.60 60004 1 2001472 BAGADE TANUJA S 12 18 48 78 73.47 HA 60005 2 3820741 PANDE ASHWINI R 12 18 48 78 73.33 60006 3 3100924 BODKE ARUN P 12 18 48 78 69.87 60007 1 2320521 MAHANGADE SURAJ B 12 18 48 78 68.13 HA 60008 OBC 1 1206325 SAMEL TANMAY S 12 18 48 78 67.07 60009 NT3 3 2901211 GITTE VIKAS B 12 18 48 78 66.40 60010 1 1306548 CHOUDHARY SHIVANI P 12 18 48 78 65.87 60011 1 1222246 NAIR PREMA K 12 18 48 78 65.00 60012 1 1700686 DESHMUKH ROHIT V 12 18 48 78 58.67 60013 ST 3 3120382 JUDE DATTA S 12 18 48 78 58.53 HA 60014 OBC 2 3720075 GUNJATE MADHAV N 12 18 48 78 57.73 60015 1 2120696 BHOSALE YOGESH R 12 18 48 78 46.80 60016 SC 2 3720210 WANKHADE DEVANAND M 12 18 48 78 0.00 HA 60017 OBC 2 3900674 GAWANDE PUJA V 13 17 48 78 81.07 60018 SC 3 2920469 GANDALE HANSRAJ M 13 17 48 78 78.40 60019 3 2721439 MINHAJ FATEMA M 13 17 48 78 75.87 60020 NT1 1 2000400 KUMAVAT RUPESH D 13 17 48 78 74.53 60021 SC 1 2204872 AUGHADE PRIYANKA N 13 17 48 78 73.73 60022 2 4520047 SANGAMWAR MANISHA B 13 17 48 78 73.47 60023 SC 1 1320911 WANKHEDE -

![Lkseokj] Iqjojh 17] 2014@Ek?K 28] 1935 No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5151/lkseokj-iqjojh-17-2014-ek-k-28-1935-no-3325151.webp)

Lkseokj] Iqjojh 17] 2014@Ek?K 28] 1935 No

jftLVªh laö Mhö ,yö&33004@99 REGD. NO. D. L. -33004/99 vlk/kj.k EXTRAORDINARY Hkkx I—[k.M 1 PART I—Section 1 izkf/dkj ls izdkf'kr PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY la. 41] ubZ fnYyh] lkseokj] iQjojh 17] 2014@ek?k 28] 1935 No. 41] NEW DELHI, MONDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2014/MAGHA 28, 1935 सामाDजक या य और अिधका@रता मंऽालय (सामाDजक याय और अिधका@रता Bवभाग) संकप ubZ fnYyh] 17 iQjojh] 2014 फाफाफा.फा ...संसंसंसं....120151201512015////05050505////201120112011----बीबीबीबी....सीसीसी ...II ...Ñ.ÑÑÑ जबAक मंडल आयोग क3 @रपोट मQ दोनU सूिचयU मQ शािमल जाितयU और समुदायU को समाAहत करके अ य Bपछड़े वग क3 सामा य के ि/य सूची और 26 रा यU और संघ रा य >ेऽU से संबंिधत अ य Bपछड़े वग क3 सामाय के ि/ य सूची को अनुबंधअनुबंध----11 मQ यथा िनAदं ट कया ण मंऽालय के संक पU के तहत अिधसूिचत Aकया गया था; और जबAक, रां श/ य Bपछड़ा वग आयोग (इसके बाद एनसीबी सी के प मQ संदिभत ) का गठन रांश/य Bपछड़ा वग आयोग अिधिनयम, 1993 (1993 का 27) क3 धारा 3 के अंतगत Aकया गया था और इसे नाग@र कU के Aकसी वग को सूिचयU मQ Bपछड़ा वग के प मQ शािमल करने संबंधी अनुरोध क3 जांच करने और ऐसी सूची मQ Aकसी Bपछड़े वग के अित समावेशन एवं अ प समावेशन क3 िशकायतU को सुनने तथा के ि/ य सरकार को सलाह देने, जैसा उपयु त हो, के िलए उ त अिधिनयम क3 धारा 9 क3 उप धारा (1) के अंतगत शD तयां ूदान क3 गई हS; और जबAक, उ त के ि/ य सूची को एनसीबीसी क3 िसफा@रशU पर संशोिधत Aकया गया था और अनुबंधअनुबंध----II मQ यथािनAदं ट संक प के तहत के ि/ य सरकार ारा समय -समय पर अिधसूिचत Aकया गया था ; 640 GI/2014 (1) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [P ART I—SEC . -

Administrative Report, Part III, Vol-VII, Bombay

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1911. VOLUME VII. BOMBAY --4>- PART III. AD~[INISTRATIVE REPORT BY P. J. MEAD AND G. LAIRD-MAcGREGOR .. I. C. S., SUPERINTENDENTS OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, BOMBAY. BOMBAY:.. PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTkAL PRESS. 1913 TABLE OF CONTENTS. • PAGES CHAPTER 1. THE ENUMEltATION OF THE PEOPLE. Establishment. Preliminary Arrangements in the Districts. Draft-ing, Translating and Printing Rules and Forms. House Numbering. The Preliminary Record. The Great Night. N on-Synchronous Tracts. Special Arrangements. The Industrial Oensus. The Census Act. District Census Oharges. Sanads and Rewards 1-8 Subsidiary Table I 9-11 ]2-14- " " II " "Ill .... ']5 Appendil: I (Bombay Oity Cf!nsus) 16-32 CHAPTER II. 'l'ABUI,ATION. General Arrangements and Location of Offices. Abstraction Offices. Office Accommodation. Provision of Furniture. Staff'. Despatch of Enumer ation Books and their Receipt in Abstraction Offices. Slip Copying. Time occupied in Slip Copying. Checking. Register A. Infirmity Slips. Rates for Copying. Printing and Supply of Slips and other Registers. Village Tables. Making up the Boxes for Sorting. and Counting the Slips 33-4fJ Sorting. Miscellaneous Details 46-53 Compilation Staff. Miscellaneous Details... 53-55 Subsidiary Table I 5,j Subsidiary Table II ••• 5n Appendix I (Abstraction Office Establishment) ••• 57-66 II II (Castes) 67 " III (Compilation Office Establishment) ••• 68 OR APTER III. ACCOUNTS. Cost of the Census. Accounts. Aden. Bombay City. Recoveries from Native States and Municipalities. Notes on the Expenditure ••• 69-72 Subsidiary Table I (Departmental Beads) ••• 73-74 Subsidiary 'l'able II (Treasury Heads) ... '" 75-76 B 1390-a CHAPTER I. THE ENUMERATION OF THE PEOPLE. -

The Odisha G a Z E T T E

The Odisha G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 53 CUTTACK, FRIDAY, JANUARY 6, 2012/PAUSA 16, 1933 MINORITIES & BACKWARD CLASSES WELFARE DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 26th December 2011 No. 1370—OBC-90/2011-M & BCW. SUBJECT—Regarding inclusion/deletion/amendments in the Central list of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in respect of the State of Odisha. ———— ORDER—Ordered that Government of India, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment Resolution F. No. 12015/13/2010-BC-II., dated the 8th December 2011 published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary Part-I, Section 1, No. 257, dated the 8th December 2011 containing inclusion/deletion/modification in the Central List of OBCs for Odisha be republished in the Extraordinary issue of the Odisha Gazette and be sent to all Departments of Government/ all Heads of Departments/all Collectors. By order of the Governor S. K. SARANGI Commissioiner-cum-Secretary to Government MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT RESOLUTION New Delhi, the 8th December 2011 F. No. 12015/13/2010-BC-II.—Whereas the Common Central List of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) comprising castes and communities included in both the lists in the report of the Mandal Commission and the lists of the State Governments were notified in respect of 26 States and Union Territories vide Ministry of Welfare Resolutions as specified in Annexure I; And whereas the National Commission for Backward Classes (hereinafter referred to as NCBC) set up under Section 3 of the National Commission for Backward Classes Act, 1993 (27 -

05 All Component All 07082017.Xlsx

IDD ComponentNameApp_No Name Father_Name Adhar_No 28091 BLC (NC) APP27802814453866 AABA BAPURAO CHOUDHARI AABA BAPURAO CHOUDHARI 28092 BLC (NC) APP27802814422605 AABASAHEB GOVERDHAN KAMBLE GOVERDHAN KAMBLE ******457196 28093 BLC (NC) APP27802814456347 AABEDA MOHAMMAD SHAIKH MOHAMMAD SHAIKH 28094 BLC (NC) APP27802814453989 AADAMBI HAJI SIPAE RAJAKSAB SIPAE 28095 BLC (NC) APP27802814189782 AADESH JAYRAM NIKAM JAYRAM NIKAM 28096 BLC (NC) APP27802814420783 Aadhika Tushar Jagtap Kalidas Hadge ******071417 28097 BLC (NC) APP27802814438339 AADITYA CHANDRAKANT PATHADE CHANDRAKANT ******930261 28098 BLC (E) APP27802814409550 Aadrawati Vishwakarma Motilal 28099 BLC (NC) APP27802814417098 AAGAZ SAGIR SHAIKH SAGIR ******798021 28100 BLC (NC) APP27802814407259 AAKANSHA AVINASH RAWOOL GOPAL ANANT RAWOOL ******425298 28101 BLC (NC) APP27802814413784 Aalakrao Shashirao Kamble Shashirao Kamble ******916653 28102 BLC (NC) APP27802814458722 aalanki shakti marpale shakti marpale 28103 BLC (NC) APP27802814404863 Aalim Abdulhamid Patel Abdulhamid Sherfodin Patel ******771825 28104 BLC (NC) APP27802814452180 AAMIR SHABUDUIN TABOLI SHABUDUIN TABOLI ******848890 28105 BLC (NC) APP27802814453540 AAMNA KHURSHID BAGBAN KHURSHID BAGBAN 28106 BLC (NC) APP27802814451413 AAMOL JANDHIN NAVLE JANDHIN NAVLE ******870122 28107 BLC (E) APP27802814447915 AANANTA SADASHIV BHAVEKAR SADASHIV BHAVEKAR ******788485 28108 BLC (NC) APP27802814452317 AANJANA SHANKAR HARALE SHANKAR TAMMA HARALE ******015301 28109 BLC (E) APP27802814470945 AANNA KALURAM NIMBALKAR KALURAM NIMBALKAR ******327472 -

Cheque No Warrant No Amount

Cheque No Warrant No Amount Beneficiary Name Reference No 1 700011 1,599.00 ASHOK KUMAR JHA 1161379 ABN AMRO BANK 0000IN30021412124862 2 700012 1,756.00 FARHAT MANZOOR 0349040400000060 JAMMU AND KASHMIR BANK LTD 0000IN30039417138523 4 700014 16,000.00 KAPIL C MEHTA 2947 THE NAWANAGAR CO OP BANK LTD 0000IN30051311712072 5 700015 8,000.00 PATEL SHREYA MUKESHBHAI 3793 CHANASMA NAGARIK SAHAKARI BANK LTD 0000IN30226914392439 13 700023 2,760.00 SANKET KUMAR SUDAN 016201005204 ICICI BANK 00001202350000197035 17 700027 4,000.00 PRASHANT VIDYADHAR MISHRA HUF 164010100187497 AXIS BANK LTD 00001201130000256712 19 700029 2,000.00 SURYANARAYANA RAJU CHINTALAPATI 102001000057854 CENTURION BANK OF PUNJAB LIMITED PUNJA 00001204340000024697 21 700031 2,000.00 V SAMPATHKUMAR 00000000000PFL001942 22 700032 2,000.00 K S ADINARAYANA 00000000000PFL001945 23 700033 2,000.00 G NAGALAKSHMI 00000000000PFL001946 24 700034 2,000.00 K MADHU SUDHANA RAO 01190006645 S B I 0000IN30039411300943 36 700046 2,000.00 P MURALI KRISHNA 0131081150100 IDBI BANK LTD 0000IN30045010781645 37 700047 4,860.00 VIJAY KRISHNA MURTHY C 234901 KARNATAKA BANK LTD 0000IN30214810345606 42 700052 2,000.00 MRS KALA KRISHNA 00000000000PFL002035 48 700058 10.00 VENKIDESWARAN 10160100128685 FEDERAL BANK LTD 00001202390000241576 49 700059 10.00 JUJANVILLY 0199 SB 01 004353 CORPORATION BANK 00001202390000241580 50 700060 10.00 ABHISHEK BAJAJ JAIN 01170063481 STATE BANK OF INDIA KHURAI BRANCH KHU 00001203160000044065 51 700061 350.00 MUKESH M UMRANIA 27510 BANK OF INDIA 00001203280000088093 52 700062 -

UNPAID DATA with Address.Xlsx

BSE LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR FINAL 2016-2017 Sno Dpid Folio/Clid Name Warrant No Total_Shares Net Amount Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Address-4 Pincode 1 120239 0000229552 LOVELY GEORGE . 1500001 100 2300.00 61/1235,ATTUKADAVIL THEKKUMTHALA ROAD KALOOR KOCHI KERALA 682017 2 IN300724 10008068 MNS ADVISORY SERVICES LTD 1500005 144 3312.00 906, DLF TOWER-A JASOLA DISTRICT CENTRE NEW DELHI 110025 3 IN302365 10535000 RAM CHANDER 1500009 500 11500.00 H NO. 68/1, V.P.O. KAILANA (KHAS), DISTT. SONEPAT, HARYANA 131301 4 IN302201 11013937 SANJAY SHARMA 1500011 500 11500.00 166, PALIKA VIHAR AMBALA CITY AMBALA 134003 5 IN301774 11141029 SURINDER SALUJA 1500013 101 2323.00 GALI NO 2 ARJUN NAGAR SIWAN ROAD KAITHAL 136027 6 120230 0000142281 MOHINDER PAL GUPTA 1500021 75 1725.00 222 - F, KANAK - MANDI JAMMU JAMMU J & K 180001 7 IN301127 15141326 BASANTI PANT 1500025 85 1955.00 C3/3 HAVELOCK COLONY LUCKNOW 226001 8 IN301696 10547007 KUNAL KOCHAR 1500041 200 4600.00 S/O HEERA LAL KOCHAR D 49 NEAR HANUMAN TEMPLE SHASTRI NAGAR BIKANER RAJASTHAN 334003 9 120180 0000010769 PRAGATI FINSTOCK PRIVATE LIMITED 1500053 144 3312.00 223 STAR CHAMBERS HARIHAR CHOWK RAJKOT GUJARAT 360001 10 120180 0000058201 KIRTIKUMAR DALASUKHRAI BUDDHDEV 1500058 144 3312.00 JAY AMBE MAA 2 MARUTI NAGAR AIR PORT ROAD RAJKOT GUJARAT 360007 11 120180 0000020401 DEVJIBHAI KALABHAI PATEL 1500068 144 3312.00 DEVVANDNA 2 SARSWATI SOCI. NIRMALA ROAD . RAJKOT GUJARAT 360005 12 IN300214 11942822 ADITYA MARINE LTD 1500093 500 11500.00 DHIRAJ CHAMBERS ROOM NO 11 12 13 PLOT -

Smart Sahayogi Details from 01-Jan-2013 to 15-Jan-2013

Smart Sahayogi details from 01-Jan-2013 to 15-Jan-2013 S.No. Sahayogi ID Sahayogi Name District State 1 8000251295 Aakash Kundlikrao Bhosale Nashik Maharashtra 2 8000231619 Aamir A Saiyed Bharuch Gujarat 3 8000233621 Abdulrehman A Tailor Bharuch Gujarat 4 8000245250 Abhay Jagdevrao Pawar Pune Maharashtra 5 8000254936 Achut Rameshrao Mahure Yavatmal Maharashtra 6 8000234153 Ajamelbhai Amrabhai Bariya Sabarkantha Gujarat 7 8000253458 Ajaybhai Parvinbhai Godhani Rajkot Gujarat 8 8000250056 Ajaybhai Ramubhai Patel Surat Gujarat 9 8000246281 Ajaypalsing Narendrasing Bhadvaria Bharuch Gujarat 10 8000207673 Ajit Pandurang Vaingankar THANE Maharashtra 11 8000223308 Ajit prabhakar Pathak Pune Maharashtra 12 8000241954 Ajitsinh Nathusinh Kaba Sabarkantha Gujarat 13 8000221977 Ajubhai Dhirubhai Raol Ahmedabad Gujarat 14 8000213063 Akash Patel Vadodara Gujarat 15 8000220378 Alka S Rajput Vadodara Gujarat 16 8000254198 Alpesh Srikant Parekh Surat Gujarat 17 8000245619 Alpeshkumar Dahyabhai Jadav Sabarkantha Gujarat 18 8000232989 Amanullah M Choksi Bharuch Gujarat 19 8000210291 Amarshibhai Premjibhai Bavaliya Surendranagar Gujarat 20 8000251243 Amarsingh Babu Rathod Surat Gujarat 21 8000184011 Ambhadevi R Sing Muzaffarpur Bihar 22 8000250768 Amit Sanjaykumar Patel Vadodara Gujarat 23 8000192725 Amitkumar Harshadbhai Parekh Surat Gujarat 24 8000250762 Amol Bhausaheb Wakchaure Nashik Maharashtra 25 8000232552 Amol Madukar Jejurkar Nashik Maharashtra 26 8000238968 Amol Rajaram Padol Nashik Maharashtra 27 8000205666 Amol Sitaram Saindre NASHIK Maharashtra -

PART III COMPENDIUM of INSTRUCTIONS ISSUED on RESERVATION for OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES in SERVICES/POSTS UNDER the GOVERNMENT of INDIA Page 1

PART III COMPENDIUM OF INSTRUCTIONS ISSUED ON RESERVATION FOR OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES IN SERVICES/POSTS UNDER THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Page 1. o.M:. No. 36012/31/90- Estt. (Sen. dated 13-8-90 437 2. OM. No. 36012/31I9O-Estt. (SCl), dated 25-9-91 438 3. OM. No. 36012/2,193-Estt.(SCl), dated 2-2-93 439 4. OM. No. 3602214193-Estt. (SCl), dated 1-6-93 440 5. OM. No. 36012/24/93-Estt. (SCl), dated 7-6-93 441 6. OM. No. 3602214193-Estt. (SCl), dated 25-6-93 442 7. OM. No. 36022/23I93-Estt. (Sen. dated 22-7-93 443 8. OM. No. 36022/13193-Estt. (SCl), dated 30-7-93 444 9. O.M. No. 36012/37193-Estt. (SCl), dated 19-8-93 445 10. OM. No. 36012/37193-Estt. (Sen. dated 19-8-93 446 11. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt.(Sen. dated 8-9-93 447 12. Resolution No. 1201l/68/93-BCC(C). dated 10-9-93 on Castes/Communities 453 13. OM. No. 36012/22/93-Estt.(SCl), dated 22-10-93 482 14. Letter No. 36012f22193-Estt. (SCl), dated 15-11-93 to Chief Secretaries of StateslUnion Territories 485 15. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt. (SCl), dated 15-11-93 491 16. OM. No. 3fi014/2193-Estt. (SCl), dated 20-12-93 493 17. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt.(Sen. dated 29-12-93 494 18. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt. (SCl), dated 30-12-93 S03 No. 36012/3119O-Estt. (seT) Government of India MInJJtry of Penonnel, PubUe Grievances " Pensions (Department of Personnel " Training) New Delhi, the 13th August, 1990.