Representations of Rural England in Contemporary Folk Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YLO89 Magazine

•YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 1 TRD COVER Youth Leaders Only / Music Resource Book / Volume 91 / Spring 2013 Cover: Red 25 Ways To Create A Crisis Page 6 When Volunteers Date Kids Page 8 The Crisis Head/Heart Disconnect Page 10 INSIDE: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Music-Media Grad Gift Page 18 Heart of the Artist: RED Page 15 Jeremy Camp Page 16 The American Bible Challenge: Jeff Foxworthy Interview Page 12 Worship Chord Charts from Gungor, Planetshakers, Elevation Worship, Everfound Page 42 y r t s i & n i c i M s u h t M u o g Y n i n z i i a m i i x d a e M M CRISIS: ® HANDLING THOSE “UH OH!” SITUATIONS •YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 2 >> TRD TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS MAIN/MILD/HOT ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY ARTIST 6 8 10 11 FEATURE 25 Ways To Create When Volunteers The Crisis I’m In A ARTICLES: Your Own Crisis Date Kids Disconnect Crisis NOW MAIN: 18 20 25 CONGRADULATIONS! PURPOSE FILM Artist: CLASS OF 2013 DVD GUNGOR Album Title: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Purpose A Creation Liturgy (Live) Song Title: Unstoppable Beautiful Things Study Theme: Sacrifice Life; Purpose Meaning Renewal MILD: 21 22 23 ELEVATION Artist: CAPITAL KINGS WORSHIP EVERFOUND Album Title: Capital Kings Nothing Is Wasted Everfound Song Title: You’ll Never Be Alone Nothing Is Wasted Never Beyond Repair Study Theme: God’s Presence Difficulty; Hope Within Grace HOT: 24 26 28 Artist: FLYLEAF JEKOB JSON Album Title: New Horizons Faith Hope Love Growing Pains Song Title: New Horizons Love Is All Brand New Study Theme: Hope; In God Love; Unconditional -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

A Secret of the Lebombo

A Secret Of The Lebombo By Bertram Mitford A Secret of the Lebombo Chapter One The Sheep-Stealers The sun flamed down from a cloudless sky upon the green and gold of the wide valley, hot and sensuous in the early afternoon. The joyous piping of sheeny spreeuws mingled with the crowing of cock koorhans concealed amid the grass, or noisily taking to flight to fuss up half a dozen others in the process. Mingled, too, with all this, came the swirl of the red, turgid river, whose high-banked, willow-fringed bed cut a dark contrasting line through the lighter hue of the prevailing bush. From his perch a white-necked crow was debating in his mind as to whether a certain diminutive tortoise crawling among the stones was worth the trouble of cracking and eating, or not. Wyvern moved stealthily forward, step by step, his pulses tingling with excitement. Then parting some boughs which came in the way he peered down into the donga which lay beneath. What he saw was not a pleasant sight, but—it was what he had expected to see. Two Kafirs were engaged in the congenial, to them, occupation of butchering a sheep. Not a pleasant sight we have said, but to this man doubly unpleasant, for this was one of his own sheep—not the first by several, as he suspected. Well, he had caught the rascals red-handed at last. Wyvern stood there cogitating as to his line of action. The Kafirs, utterly unsuspicious of his presence, went on with their cutting and quartering, chattering gleefully in their deep-toned voices, as to what good condition the meat was in, and what a succulent feast they would have when the darkness of night should enable them to fetch it away to the huts from this remote and unsuspected hiding-place. -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

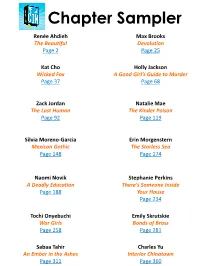

Chapter Sampler

Chapter Sampler Renée Ahdieh Max Brooks The Beautiful Devolution Page 2 Page 25 Kat Cho Holly Jackson Wicked Fox A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder Page 37 Page 68 Zack Jordan Natalie Mae The Last Human The Kinder Poison Page 92 Page 119 Silvia Moreno-Garcia Erin Morgenstern Mexican Gothic The Starless Sea Page 148 Page 174 Naomi Novik Stephanie Perkins A Deadly Education There’s Someone Inside Page 188 Your House Page 234 Tochi Onyebuchi Emily Skrutskie War Girls Bonds of Brass Page 258 Page 281 Sabaa Tahir Charles Yu An Ember in the Ashes Interior Chinatown Page 311 Page 360 The Beautiful Renée Ahdieh Click here to learn more about this book! RENé E AHDIEH G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS G. P. Putnam’s Sons an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York Copyright © 2019 by Renée Ahdieh. Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. G. P. Putnam’s Sons is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 9781524738174 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Design by Theresa Evangelista. Text set in Warnock Pro. -

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES

When Cultures Collide: LEADING ACROSS CULTURES Richard D. Lewis Nicholas Brealey International 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page i # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page ii page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iii ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page iv page # blind folio 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page v ✦ When Cultures Collide ✦ LEADING ACROSS CULTURES A Major New Edition of the Global Guide Richard D. Lewis # bli d f li 31573 01 i-xxiv 1-176 r13rm 8/18/05 2:56 PM Page vi First published in hardback by Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 1996. This revised edition first published in 2006. 100 City Hall Plaza, Suite 501 3-5 Spafield Street, Clerkenwell Boston, MA 02108, USA London, EC1R 4QB, UK Information: 617-523-3801 Tel: +44-(0)-207-239-0360 Fax: 617-523-3708 Fax: +44-(0)-207-239-0370 www.nicholasbrealey.com www.nbrealey-books.com © 2006, 1999, 1996 by Richard D. Lewis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell. 10 09 08 07 06 12345 ISBN-13: 978-1-904838-02-9 ISBN-10: 1-904838-02-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, Richard D. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Focus on Dance Education

FOCUS ON DANCE EDUCATION: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating, Performing, Responding, Connecting In Partnership with the International Guild of Musicians in Dance (IGMID) 17th Annual Conference October 7-11, 2015 Phoenix, Arizona CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS National Dance Education Organization Kirsten Harvey, MFA Editor Focus on Dance Education: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating Performing, Responding, Connecting Editorial Introduction In October 2015, the National Dance Education Organization met for their annual conference in Phoenix, Arizona to celebrate and honor the legacy, and individuality of the NDEO dance community. The warm spirit of Phoenix resonated with each educator and artist that came together at the beautiful Pointe Hilton Tapatio Cliffs Resort. Over 150 workshops, papers presentations, panels, master classes, social events, and performances were offered including full day pre-conference intensives that preceded the official start of the conference. The range of offerings for dance educators included a variety of experiences to foster inspiration, education, response, dialogue and connection to one another. Contributions to Focus on Dance Education: Engaging in the Artistic Processes: Creating Performing, Responding, Connecting Conference Proceedings include paper presentations, panel discussions, workshops, and movement sessions presented from October 7-11, 2015. The proceedings include 4 abstracts, 9 full papers, 6 movement session summaries, 6 summary of workshop presentations, 2 panel discussion summaries, and 1 special interest group summary. One of the broadest ranges of submissions since I have been editing the proceedings. The NDEO top paper selection committee selected Caroline Clark’s paper titled “We Learned to Perform by Performing: Oral Histories of Ballet Dancers in a Beer Hall” for the Top Paper Citation. -

San Pedro Sing

THE SOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING JULY - AUGUST &2007 OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTSFolkWorks IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA Page FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 7 Number 4 July-August 2007 New World Flamenco Festival La Flor de la Vida, August 10-19 See page 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE FREE SUMMER CONCERT LISTINGS HAWAIIAN FESTIVALS SEA SHANTIES PLUS... KEYS TO THE HIGHWAY ..that reminds me... ...and More!... cover photo: PHOTO OF JUAN OGALLA BY MIGUEL ANDY MOGG Page 2 FolkWorks JULY - AUGUST 2007 EDITORIAL his July/August issue in your musician teaching listings, etc. Be hands lists a plethora of sum- sure to look at the website and Yahoo PUBLISHERS & EDITORS Tmer concerts. Look at page 3 Group for announcements. We plan to Leda & Steve Shapiro for this summer’s offerings at the Skir- continue our ongoing columns about LAYOUT & PRODUCTION ball, Culver City, Japan American Mu- Music Theory, Old Time Music, Events Alan Stone Creative Services seum, Grand Performances, the Santa Around Town and all the other regular FEATURED WRITERS Monica Pier and the Levitt Pavillion. columnists you love. In fact now you Ross Altman, How Can I Keep From Talking At this time each year, we search will be able to read them online and David Bragger, Old-Time Oracle through the listings and mark in our not have to worry about finding that Valerie Cooley, ...that reminds me... calendar all the wonderful concerts old newspaper article. There is a good Linda Dewar, Grace Notes Roger Goodman, Keys to the Highway we plan on attending. We want here search engine on the site and you can David King, Dirt to thank all the producers who spend find what you want. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center, our multimedia, folk-related archive). All recordings received are included in Publication Noted (which follows Off the Beaten Track). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention Off The Beaten Track. Sincere thanks to this issues panel of musical experts: Roger Dietz, Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Andy Nagy, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Elijah Wald, and Rob Weir. liant interpretation but only someone with not your typical backwoods folk musician, Jodys skill and knowledge could pull it off. as he studied at both Oberlin and the Cin- The CD continues in this fashion, go- cinnati College Conservatory of Music. He ing in and out of dream with versions of was smitten with the hammered dulcimer songs like Rhinordine, Lord Leitrim, in the early 70s and his virtuosity has in- and perhaps the most well known of all spired many players since his early days ballads, Barbary Ellen. performing with Grey Larsen. Those won- To use this recording as background derful June Appal recordings are treasured JODY STECHER music would be a mistake. I suggest you by many of us who were hearing the ham- Oh The Wind And Rain sit down in a quiet place, put on the head- mered dulcimer for the first time. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

The First Benefit Concert for the Alan Surtees Trust Took Place in the Fabulous Adam Ballroom at the Lion Hotel in Shrewsbury on 10Th January 2020

The first benefit concert for the Alan Surtees Trust took place in the fabulous Adam Ballroom at the Lion Hotel in Shrewsbury on 10th January 2020. The room was full, tickets had sold out soon after the concert was announced shortly after the festival last August. Getting artists of the calibre of John Jones, Steve Knightley, Phil Beer, Hannah James and Grace Petrie onto the same bill for an evening concert is testimony not only to the purpose of the trust but also to the standing of Alan himself. All the artists gave their time for free. The concert was introduced and compared by Dave Cowing, the chairman of the trust and a friend of Alan for over 30 years. First to perform was Hannah James. She had known Alan since first performing at the festival aged 14 when a member of Kerfuffle. Alan had encouraged Hannah to develop her ideas around music and dance. She instigated the idea of the trust soon after Alan passed away and emailed her friends to help make it happen. For this gig, Hannah had flown over specially from a winter sojourn in Slovenia. Perched on a chair, Hannah played a piano accordion almost as large as herself. She began with a song from that first set with Kerfuffle and continued with some tunes, two yodelling songs she learnt from Austrian friends and finished with a very moving song she wrote last year about the shootings in a school in Florida: "... friends fly high and dreams run deep ...". The second part of the first half saw Phil Beer join Steve Knightley to re-form the original Show of Hands duo for one evening only.