Scottish Migration to Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Imeacht Na Niarlí the Flight of the Earls 1607 - 2007 Imeacht Na Niarlí | the Flight of the Earls

Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Roddy Hegarty Memorial Library & Archive Imeacht Na nIarlí The Flight of the Earls 1607 - 2007 Imeacht Na nIarlí | The Flight of the Earls Introduction 1 The Nine Years War 3 Imeacht na nIarlaí - The Flight of the Earls 9 Destruction by Peace 17 Those who left Ireland in 1607 23 Lament for Lost Leaders 24 This publication and the education and outreach project of Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library & Archive, of which it forms part, have been generously supported by Heritage Lottery Fund Front cover image ‘Flight of the Earls’ sculpture in Rathmullan by John Behan | Picture by John Campbell - Strabane Imeacht Na nIarlí | The Flight of the Earls Introduction “Beside the wave, in Donegal, The face of Ireland changed in September 1607 when and outreach programme supported by the Heritage the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell along with their Lottery Fund. The emphasis of that exhibition was to In Antrim’s glen or far Dromore, companions stept aboard a ship at Portnamurry near bring the material held within the library and archive Or Killillee, Rathmullan on the shores of Lough Swilly and departed relating to the flight and the personalities involved to a their native land for the continent. As the Annals of wider audience. Or where the sunny waters fall, the Four Masters records ‘Good the ship-load that was In 2009, to examine how those events played a role At Assaroe, near Erna’s shore, there, for it is certain that the sea has never carried in laying the foundation for the subsequent Ulster nor the wind blown from Ireland in recent times a This could not be. -

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper the Plantation

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper The Plantation of Ulster and the creation of the county of Londonderry On the 28th January 1610 articles of agreement were signed between the City of London and James I, king of England and Scotland, for the colonisation of an area in the province of Ulster which was to become the county of Londonderry. This agreement modified the original plan for the Plantation of Ulster which had been drawn up in 1609. The area now to be allocated to the City of London included the then county of Coleraine,1 the barony of Loughinsholin in the then county of Tyrone, the existing town at Derry2 with adjacent land in county Donegal, and a portion of land on the county Antrim side of the Bann surrounding the existing town at Coleraine. The Londoners did not receive their formal grant from the Crown until 1613 when the new county was given the name Londonderry and the historic site at Derry was also renamed Londonderry – a name that is still causing controversy today.3 The baronies within the new county were: 1. Tirkeeran, an area to the east of the Foyle river which included the Faughan valley. 2. Keenaght, an area which included the valley of the river Roe and the lowlands at its mouth along Lough Foyle, including Magilligan. 3. Coleraine, an area which included the western side of the lower Bann valley as far west as Dunboe and Ringsend and stretching southwards from the north coast through Macosquin, Aghadowey, and Garvagh to near Kilrea. 4. Loughinsholin, formerly an area in county Tyrone, situated between the Sperrin mountains in the west and the river Bann and Lough Neagh on the east, and stretching southwards from around Kilrea through Maghera, Magherafelt and Moneymore to the river Ballinderry. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

Marriage Between the Irish and English of Fifteenth-Century Dublin, Meath, Louth and Kildare

Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires' Booker, S. (2013). Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires'. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 113, 219-250. https://doi.org/10.3318/PRIAC.2013.113.02 Published in: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2013 Royal Irish Academy. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:25. Sep. 2021 Intermarriage in fifteenth century Ireland: the English and Irish in the ‘four obedient shires’ SPARKY BOOKER* Department of History and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin [Accepted 1 March 2012.] Abstract Many attempts have been made to understand and explain the complicated relationship between the English of Ireland and the Irish in the later middle ages. -

Pacata Hibernia : Or, a History of the Wars in Ireland During the Reign Of

Columbia ZHnitiersiftp intt)eCitpoflfttjgork LIBRARY DONNELt, O'SILKVAX BKAKK. From a jioitiait in Ihc Nalional GMery, Dublin. Vol. II Frontispiece. PACATA HIBERNTA OR A HISTORY OF THE WARS IN IRELAND BDIUNG THE EEIGN OF (Si u c e n E I i 5 a I) e 1 1) KSPECIALLY WITHIN THE PROVINCE OF MUNSTER UNDER THE GOVERNMENT OF SIR GEORGE CAREW AND COMPILED BY HIS DIRECTION AND APPOINTMENT EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY STANDTSH OTtRADY WITH PORTRAITS, MAPS AND PLANS VOL. 11. JjOW2s^EY .^' CO. LniiTKD 12, YORK STREET, COA^ENT GARDEN, LONDON 1896 LONDON: PRINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, LD., ST. John's house, clerkenwell, k.c. —; CONTENTS OF VOLUME II. THE SECOND BOOK— {continued). CHAPTER XIII. t. The Castle of Rincorran, guarded by the Spaniards, besieged and the Spaniards repulsed—The Castle of Rincorran battered by the Lord President—A remarkable skirmish between us and the Spaniards that attempted to relieve Rincorran—The Lord Audley, Sir Oliver Saint-John, and Sir Garret Harvy hurt—A Spanish commander taken prisoner—The enemy demanded a; parley, but the Lord President refused to treat with the messenger— The com- mander parleyed, but his offers were not accepted—The enemy endeavoured to make an escape, wherein many were slain and taken Prisoners—Sir Oliver Saint-John sent from the Lord Deputy with directions to the Lord President The reasons that induced the Lord President to receive the Spaniards that were in Rincorran to mercy—The agreement between the Lord President and the Spanish commander that was in Rincorran ..... ^ .. CHAPTER XIV. -

Scotch-Irish"

HON. JOHN C. LINEHAN. THE IRISH SCOTS 'SCOTCH-IRISH" AN HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL MONOGRAPH, WITH SOME REFERENCE TO SCOTIA MAJOR AND SCOTIA MINOR TO WHICH IS ADDED A CHAPTER ON "HOW THE IRISH CAME AS BUILDERS OF THE NATION' By Hon. JOHN C LINEHAN State Insurance Commissioner of New Hampshire. Member, the New Hampshire Historical Society. Treasurer-General, American-Irish Historical Society. Late Department Commander, New Hampshire, Grand Army of the Republic. Many Years a Director of the Gettysburg Battlefield Association. CONCORD, N. H. THE AMERICAN-IRISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY 190?,, , , ,,, A WORD AT THE START. This monograph on TJic Irish Scots and The " Scotch- Irish" was originally prepared by me for The Granite Monthly, of Concord, N. H. It was published in that magazine in three successiv'e instalments which appeared, respectively, in the issues of January, February and March, 1888. With the exception of a few minor changes, the monograph is now reproduced as originally written. The paper here presented on How the Irish Came as Builders of The Natioji is based on articles contributed by me to the Boston Pilot in 1 890, and at other periods, and on an article contributed by me to the Boston Sunday Globe oi March 17, 1895. The Supplementary Facts and Comment, forming the conclusion of this publication, will be found of special interest and value in connection with the preceding sections of the work. John C. Linehan. Concord, N. H., July i, 1902. THE IRISH SCOTS AND THE "SCOTCH- IRISH." A STUDY of peculiar interest to all of New Hampshire birth and origin is the early history of those people, who, differing from the settlers around them, were first called Irish by their English neighbors, "Scotch-Irish" by some of their descendants, and later on "Scotch" by writers like Mr. -

The Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster : The Story of Co. Fermanagh Fermanagh County Museum Enniskillen Castle Castle Barracks Enniskillen Co. Fermanagh A Teachers Aid produced by N. Ireland BT74 7HL Fermanagh County Museum Education Service. Tel: + 44 (0) 28 6632 5000 Fax: +44 (0) 28 6632 7342 Email: [email protected] Web:www.enniskillencastle.co.uk Suitable for Key Stage 3 Page 1 The Plantation Medieval History The Anglo-Normans conquered Ireland in the late 12th century and by 1250 controlled three-quarters of the country including all the towns. Despite strenuous efforts, they failed to conquer the north west of Ireland and this part of Ireland remained in Irish hands until the end of the 16th century. The O’Neills and O’Donnells controlled Tyrone and Donegal and, from about 1300, the Maguires became the dominant clan in an area similar to the Crowning of a Maguire Chieftain at Cornashee, near Lisnaskea. Conjectural drawing by D Warner. Copyright of Fermanagh County Museum. present county of Fermanagh. In the rest of the country Anglo Norman influence had declined considerably by the 15th century, their control at that time extending only to the walled towns and to a small area around Dublin, known as the Pale. However, from the middle of the 16th century England gradually extended its control over the country until the only remaining Gaelic stronghold was in the central and western parts of the Province of Ulster. Gaelic Society Gaelic Ireland was a patchwork of independent kingdoms, each ruled by a chieftain and bound by a common set of social, religious and legal traditions. -

Town of Chelmsford of Town

Town of Chelmsford Annual Town Report Fiscal 2020 Annual Town of Chelmsford Town Town of Chelmsford Annual ToWn Report • Fiscal 2020 Town of Chelmsford • 50 Billerica Road • Chelmsford, MA 01824 Phone: (978) 250-5200 • www.chelmsfordma.gov Community Profile & Map Town Directory 2020 Quick Facts Town Departments & Services ............... 978-250-5200 Utilities & Other Useful Numbers Accounting ............................................... 978-250-5215 Cable Access/Telemedia ......................... 978-251-5143 Incorporated: ...................................May 1655 Total Single Family Units: ............................................. 9,060 Animal Control ......................................... 978-256-0754 Cable Television/Comcast ..................... 888-663-4266 Type of Government: ..................Select Board Total Condo Units: ..........................................................2,692 Assessors .................................................. 978-250-5220 Chelmsford Water Districts Town Manager Total Households: .........................................................13,646 Appeals, Board of .................................... 978-250-5231 Center District ...................................... 978-256-2381 Representative Town Meeting [1]Avg. Single Family Home Value: ........................$447,600 Auditor ...................................................... 978-250-5215 East District .......................................... 978-453-0121 County: ........................................... Middlesex Tax -

The Plantation of Ulster Document Study Pack Staidéar Bunfhoinsí

Donegal County Archives Cartlann Chontae Dhún na nGall The Plantation of Ulster Document Study Pack Staidéar Bunfhoinsí Plandáil Uladh Contents PAGE Ulster before Plantation 2 O’Doherty’s Rebellion and the Irish in Ulster 3 The Plantation of East Ulster 4 The Scheme for Plantation 5 The King’s Commissioners and Surveys 6 The Grantees – 7 • Undertakers 7 • Servitors 7 • Native Irish 7 • The London Companies 8 • Other Grantees 8 Buildings and Towns – The Birth of the Urban Landscape 9 The Natives and the Plantation 10 The Cultural Impact of the Plantation 11 The Plantation in Donegal 11 The Plantation in Londonderry 13 The 1641 Rebellion and the Irish Confederate Wars 14 The Success of the Plantation of Ulster 16 Who’s who: 17 • The Native Irish 17 • King, Council and Commissioners 18 The Protestant Reformation 19 Dealing with Documents 20 Documents and Exercises 21 Glossary 24 Additional Reading and Useful Websites 25 Acknowledgements 25 | 1 | Ulster before Plantation On the 14th of September 1607 a ship left sides and now expected to be rewarded for the Donegal coast bound for Spain. On board their loyalty to the crown. Also living in the were a number of Irish families, the noblemen province were numbers of ex-soldiers and of Ulster, including: Hugh O’Neill, Earl of officials who also expected to be rewarded for Tyrone, Ruairí O’Donnell, Earl of Tír Chonaill, long years of service. Cú Chonnacht Maguire, Lord of Fermanagh and ninety nine members of their extended O’Neill’s and O’Donnell’s lands were immediately families and households. -

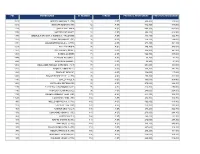

FY20 Old to New Values

PID OWNER NAME ST NUMBER STREET PREVIOUS ASSESSMENT PREVIOUS ASSESSMENT 1515 GRIFFIN GERALD T. (TE) 8 A ST 288,200 310,600 1516 NAMVAR NAZANIN (TE) 12 A ST 332,500 338,500 1379 SNYER WILLIAM R 13 A ST 468,300 457,000 1374 SUPRENANT SCOTT 18 A ST 204,100 214,900 1378 BREAULT DAVID R. & KAREN A., TRUSTEES 23 A ST 313,100 322,300 1373 DOWLING JOHN T (TE) 24 A ST 274,100 289,000 1371 LOUANGPHIXAI LILA L. (JTRS) 30 A ST 271,800 301,100 1514 PATTEN KAREN 38 A ST 346,300 343,500 11167 RYCHALSKY, ERIN J 65 A ST 356,500 381,900 1203 RIVERA ANDRES 71 A ST 366,300 387,600 1484 SCARVALAS GARY J 72 A ST 39,200 41,200 1485 MALCOLM DONNA J 76 A ST 39,200 41,200 1202 BEAUDOIN RONALD & BRENDA, TSTS 77 A ST 294,600 303,000 1201 APONTE, KIMBERLY L 83 A ST 316,200 341,700 1483 TOWN OF DRACUT 88 A ST 112,000 117,600 1482 KRUGH KENNETH W. (JTRS) 90 A ST 290,200 312,800 1191 BAILEY PAUL R 92 A ST 303,000 309,400 1200 KIGGUNDU SEPIRIA (TE) 93 A ST 272,000 326,300 1199 FITZGERALD RAYMOND J.(TE) 95 A ST 275,300 296,800 1190 PROVOST ALAN MICHAEL 98 A ST 249,000 254,600 1198 DARES KIMBERLY JEAN IND. 101 A ST 277,300 302,800 11649 COGAN MICHAEL (TE) 104 A ST 284,700 306,700 997 MELLO JEFFREY A. -

Female Irish Catholic Rebels in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Edwin Marshall Galloway East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2011 Thieves Apostates and Bloody Viragos: Female Irish Catholic Rebels in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Edwin Marshall Galloway East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Galloway, Edwin Marshall, "Thieves Apostates and Bloody Viragos: Female Irish Catholic Rebels in the Irish Rebellion of 1641." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1322. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1322 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thieves, Apostates, and “Bloody Viragos:” Female Irish Catholic Rebels in the Irish Rebellion of 1641 ____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History ____________________ by E. Marshall Galloway August 2011 ____________________ Brian Maxson., PhD, Chair Melvin E. Page, PhD Judith B. Slagle, PhD Keywords: Ireland, Irish Rebellion of 1641, 1641 Depositions, Gender ABSTRACT Thieves, Apostates, and “Bloody Viragos:” Female Irish Catholic Rebels in the Irish Rebellion of 1641 by E. Marshall Galloway The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the roles played by Irish Catholic women in the Irish Rebellion of 1641.