The New Interculturalism Mcivor Final Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Larry Reynolds, Fiddler: US Rep

November 2012 Boston’s hometown VOL. 23 #11 journal of Irish culture. $1.50 Worldwide at All contents copyright © 2012 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. bostonirish.com BIR cites Rep. Neal, Muses, and Feeneys The Boston Irish Reporter hosted its third annual Boston Irish Honors on Fri., Oct. 19, at the Seaport Hotel on the South Boston waterfront. The event, which marked the 22nd anni- versary of the BIR, drew more than 350 persons to the mid-day luncheon. In his prepared remarks, publisher Ed Forry said, “In hon- oring these exemplary families and individu- als who em- body the fin- est qualities of our people, we seek to h o n o r t h e memories of our ancestors who came here in bygone days when it was far from clear that we could make this place our home. How proud those early immigrants would be of their descendants, who have made Boston a welcoming place— Larry Reynolds leading a session at the Green Briar Irish Pub in Brighton. not only for new waves of Irish Photo courtesy of Bill Brett, from “Boston: An Extended Family” © 2007 entrepreneurs and workers, but for people from around the globe. “Today’s honorees — the Muse family, the Feeney brothers and Remembering Larry Reynolds, fiddler: US Rep. Richard Neal—are agents of idealism and ingenu- ity who represent the best of the ‘He never, ever got tired of the music’ Boston Irish experience. They no room for all of them to come simply passed along by word of are devoted to a level of profes- By Sean Smith Ui Cheide, a sean-nos singer sionalism in their chosen fields and say goodbye to him. -

Scottish Migration to Ireland

SCOTTISH MIGRATION TO IRELAND (1565 - 16(7) by r '" M.B.E. PERCEVAL~WELL A thesis submitted to the Faculty of er.duet. Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts. Department of History, McGIII UnIversity, Montreal. August,1961 • eRgFAcE ------..--- ---------------..--------------..------ .. IN..-g.JCTI()tf------------------..--·----------...----------------..-..- CHAPTER ONE Social and Economic Conditions in UI ster and Scotland..--.... 17 CtMPTER TWO Trade and Its Influence on Mlgratlon-------------------..-- 34 CHAPTER ItREE Tbe First Permanent Foothold---------..-------------------- 49 CHAPTER FOUR Scottish Expansion In Ir.land......-------------..-------......- 71 CHAPTER FIVE Rei 1910n and MIgratlon--------------·------------------------ 91 CHAPTEB SIX The Flnel Recognition of the Scottish Position In I reI and....-------·-----------------------------.....----------..... 107 COffCl,US IQN-..--------------------·---------·--·-----------..------- 121 BIBl,1 ~--------------.-- ....-----------------.-----....-------- 126 - 11 - All populatlons present the historian with certain questions. Their orIgins, the date of their arrival, their reason for coming and fInally, how they came - all demand explanatIon. The population of Ulster today, derived mainly from Scotland, far from proving 8n exception, personifies the problem. So greatly does the population of Ulster differ from the rest of Ireland that barbed wire and road blocks period Ically, even now, demark the boundaries between the two. Over three centuries after the Scots arrived, they stili maintain their differences from those who Inhabited Ireland before them. The mein body of these settlers of Scottish descent arrived after 1607. The 'flight of the earls,' when the earls of Tyron. and Tyrconnell fled to the conTinent, left vast areas of land In the hands of the crown. Although schemes for the plantation of U.lster had been mooted before, the dramatic exit of the two earls flnelly aroused the English to action. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.Thc sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Pagc(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing pagc(s) or section, they arc spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed cither blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame* If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005

Register of Insurance & Reinsurance Intermediaries European Communities (Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005 Insurance Mediation Register: A list of Insurance & Reinsurance Intermediaries registered under the European Communities (Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005 (as amended). Registration of insurance/reinsurance intermediaries by the Central Bank of Ireland, does not of itself make the Central Bank of Ireland liable for any financial loss incurred by a person because the intermediary, any of its officers, employees or agents has contravened or failed to comply with a provision of these regulations, or any condition of the intermediary’s registration, or because the intermediary has become subject to an insolvency process. Ref No. Intermediary Registered As Registered on Tied to* Persons Responsible** Passporting Into C29473 123 Money Limited Insurance Intermediary 23 May 2006 Holmes Alan France t/a 123.ie,123.co.uk Paul Kierans Germany 3rd Floor Spain Mountain View United Kingdom Central Park Leopardstown Dublin 18 C31481 A Better Choice Ltd Insurance Intermediary 31 May 2007 Sean McCarthy t/a ERA Downey McCarthy, ERA Mortgages, Remortgages Direct 8 South Mall Cork C6345 A Callanan & Co Insurance Intermediary 31 July 2007 5 Lower Main Street Dundrum Dublin 14 C70109 A Plus Financial Services Limited Insurance Intermediary 18 January 2011 Paul Quigley United Kingdom 4 Rathvale Park Ayrfield Dublin 13 C1400 A R Brassington & Company Insurance Intermediary 31 May 2006 Cathal O'brien United Kingdom Limited t/a Brassington Insurance, Quickcover IFG House Booterstown Hall Booterstown Co Dublin C42521 A. Cleary & Sons Ltd Insurance Intermediary 30 March 2006 Deirdre Cleary Kiltimagh Enda Cleary Co. Mayo Helen Cleary Paul Cleary Brian Joyce Run Date: 07 August 2014 Page 1 of 398 Ref No. -

Forecast Error: How to Predict an Election: Part 1: Polls

FORECAST ERROR: HOW TO PREDICT AN ELECTION: PART 1: POLLS "Any attempt to predict the future depends on it resembling the past"[0423l] Cartoon from the Daily Mirror, May 27 1970, as reproduced in “The British General Election of 1970”, Butler and Pinto‐Duschinsky. 1971; ISBN: 978‐1‐349‐01095‐0 1. INTRODUCTION The "Forecast Error" series of articles started examining election predictors in 2015. Each article considered many predictors, but each article covered just one election. This article marks a new chapter in the "Forecast Error" series where we examine an individual class of predictor more closely across many elections. We begin with possibly the most prominent: opinion polls. A political opinion poll is a method of assessing a population’s opinion on the matters of the day by asking a sample of people. A subset is the voter intention poll, which asks each sampled person how they intend to vote in an election. Pollsters then turn their intention into votes by applying certain assumptions. Those assumptions may not be valid over the long term, or even from one election to the next. The problem faced when writing about opinion polls is not how to start writing, it's how to stop. It is entirely possible to write a full article about any given facet of opinion polling, and examples immediately spring to mind: whether one should still use "margin of error" for online panel polling, Nate Silver's insight regarding the borrowing of strength from polls in similar states, is it meaningful to speak of a polling threshold, and so on. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

Marriage Between the Irish and English of Fifteenth-Century Dublin, Meath, Louth and Kildare

Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires' Booker, S. (2013). Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires'. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 113, 219-250. https://doi.org/10.3318/PRIAC.2013.113.02 Published in: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2013 Royal Irish Academy. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:25. Sep. 2021 Intermarriage in fifteenth century Ireland: the English and Irish in the ‘four obedient shires’ SPARKY BOOKER* Department of History and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin [Accepted 1 March 2012.] Abstract Many attempts have been made to understand and explain the complicated relationship between the English of Ireland and the Irish in the later middle ages. -

Pacata Hibernia : Or, a History of the Wars in Ireland During the Reign Of

Columbia ZHnitiersiftp intt)eCitpoflfttjgork LIBRARY DONNELt, O'SILKVAX BKAKK. From a jioitiait in Ihc Nalional GMery, Dublin. Vol. II Frontispiece. PACATA HIBERNTA OR A HISTORY OF THE WARS IN IRELAND BDIUNG THE EEIGN OF (Si u c e n E I i 5 a I) e 1 1) KSPECIALLY WITHIN THE PROVINCE OF MUNSTER UNDER THE GOVERNMENT OF SIR GEORGE CAREW AND COMPILED BY HIS DIRECTION AND APPOINTMENT EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY STANDTSH OTtRADY WITH PORTRAITS, MAPS AND PLANS VOL. 11. JjOW2s^EY .^' CO. LniiTKD 12, YORK STREET, COA^ENT GARDEN, LONDON 1896 LONDON: PRINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, LD., ST. John's house, clerkenwell, k.c. —; CONTENTS OF VOLUME II. THE SECOND BOOK— {continued). CHAPTER XIII. t. The Castle of Rincorran, guarded by the Spaniards, besieged and the Spaniards repulsed—The Castle of Rincorran battered by the Lord President—A remarkable skirmish between us and the Spaniards that attempted to relieve Rincorran—The Lord Audley, Sir Oliver Saint-John, and Sir Garret Harvy hurt—A Spanish commander taken prisoner—The enemy demanded a; parley, but the Lord President refused to treat with the messenger— The com- mander parleyed, but his offers were not accepted—The enemy endeavoured to make an escape, wherein many were slain and taken Prisoners—Sir Oliver Saint-John sent from the Lord Deputy with directions to the Lord President The reasons that induced the Lord President to receive the Spaniards that were in Rincorran to mercy—The agreement between the Lord President and the Spanish commander that was in Rincorran ..... ^ .. CHAPTER XIV. -

SU Education Officer Under Criticism

T H E I N D E P E N D E N T S T U D E N T N E W S P A P E R O F T R I N I T Y C O L L E G E D U B L I N [email protected] 10th February 2004 Vol 56; No.6 TrinityNews Always Free WWININ PPASSASS TTOO SUSU EELECTIONLECTION SSPORTPORT FILMILM FESTIVESTIVALAL! PECIAL Trinity Camogie win F F ! SSPECIAL at Colours SEE FILM PAGE 15 PAGE 3 PAGE 20 College News 21million for Trinity SWSS and Sinn Fein disciplined over Taoiseach protest Nanoscience research..p.2 Tim Walker nominal fine and a letter liberties following the of apology from the ‘War on Terror’. They Grant to develop MMR offending parties. have a ‘you’re either Vaccine........................p.3 THE SOCIALIST The anticipated with us or against us’ Worker (SWSS) and Sinn Students’ Union demon- attitude." Fein societies faced dis- stration against the edu- Ciaran Doherty, chair International ciplinary action from cation cutbacks failed to of the Trinity Sinn Fein Student News College following their materialise. Instead, the society, was more cir- involvement in the vocal Taoiseach was presented cumspect. "This was a UK Law schools announce protest that greeted with a petition of 1000 good-natured protest, new entrance exam Taoiseach Bertie Ahern signatures, with a cover involving 20 or 30 people ........................................p.4 on his visit to the letter drafted by SU at most," he commented. College Historical President Annie Gatling, "We just felt it was Forum Society on the evening of criticising the govern- important to make the Tuesday, January 28th. -

Scotch-Irish"

HON. JOHN C. LINEHAN. THE IRISH SCOTS 'SCOTCH-IRISH" AN HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL MONOGRAPH, WITH SOME REFERENCE TO SCOTIA MAJOR AND SCOTIA MINOR TO WHICH IS ADDED A CHAPTER ON "HOW THE IRISH CAME AS BUILDERS OF THE NATION' By Hon. JOHN C LINEHAN State Insurance Commissioner of New Hampshire. Member, the New Hampshire Historical Society. Treasurer-General, American-Irish Historical Society. Late Department Commander, New Hampshire, Grand Army of the Republic. Many Years a Director of the Gettysburg Battlefield Association. CONCORD, N. H. THE AMERICAN-IRISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY 190?,, , , ,,, A WORD AT THE START. This monograph on TJic Irish Scots and The " Scotch- Irish" was originally prepared by me for The Granite Monthly, of Concord, N. H. It was published in that magazine in three successiv'e instalments which appeared, respectively, in the issues of January, February and March, 1888. With the exception of a few minor changes, the monograph is now reproduced as originally written. The paper here presented on How the Irish Came as Builders of The Natioji is based on articles contributed by me to the Boston Pilot in 1 890, and at other periods, and on an article contributed by me to the Boston Sunday Globe oi March 17, 1895. The Supplementary Facts and Comment, forming the conclusion of this publication, will be found of special interest and value in connection with the preceding sections of the work. John C. Linehan. Concord, N. H., July i, 1902. THE IRISH SCOTS AND THE "SCOTCH- IRISH." A STUDY of peculiar interest to all of New Hampshire birth and origin is the early history of those people, who, differing from the settlers around them, were first called Irish by their English neighbors, "Scotch-Irish" by some of their descendants, and later on "Scotch" by writers like Mr. -

Town of Chelmsford of Town

Town of Chelmsford Annual Town Report Fiscal 2020 Annual Town of Chelmsford Town Town of Chelmsford Annual ToWn Report • Fiscal 2020 Town of Chelmsford • 50 Billerica Road • Chelmsford, MA 01824 Phone: (978) 250-5200 • www.chelmsfordma.gov Community Profile & Map Town Directory 2020 Quick Facts Town Departments & Services ............... 978-250-5200 Utilities & Other Useful Numbers Accounting ............................................... 978-250-5215 Cable Access/Telemedia ......................... 978-251-5143 Incorporated: ...................................May 1655 Total Single Family Units: ............................................. 9,060 Animal Control ......................................... 978-256-0754 Cable Television/Comcast ..................... 888-663-4266 Type of Government: ..................Select Board Total Condo Units: ..........................................................2,692 Assessors .................................................. 978-250-5220 Chelmsford Water Districts Town Manager Total Households: .........................................................13,646 Appeals, Board of .................................... 978-250-5231 Center District ...................................... 978-256-2381 Representative Town Meeting [1]Avg. Single Family Home Value: ........................$447,600 Auditor ...................................................... 978-250-5215 East District .......................................... 978-453-0121 County: ........................................... Middlesex Tax -

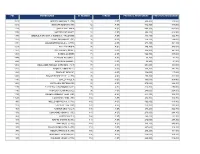

FY20 Old to New Values

PID OWNER NAME ST NUMBER STREET PREVIOUS ASSESSMENT PREVIOUS ASSESSMENT 1515 GRIFFIN GERALD T. (TE) 8 A ST 288,200 310,600 1516 NAMVAR NAZANIN (TE) 12 A ST 332,500 338,500 1379 SNYER WILLIAM R 13 A ST 468,300 457,000 1374 SUPRENANT SCOTT 18 A ST 204,100 214,900 1378 BREAULT DAVID R. & KAREN A., TRUSTEES 23 A ST 313,100 322,300 1373 DOWLING JOHN T (TE) 24 A ST 274,100 289,000 1371 LOUANGPHIXAI LILA L. (JTRS) 30 A ST 271,800 301,100 1514 PATTEN KAREN 38 A ST 346,300 343,500 11167 RYCHALSKY, ERIN J 65 A ST 356,500 381,900 1203 RIVERA ANDRES 71 A ST 366,300 387,600 1484 SCARVALAS GARY J 72 A ST 39,200 41,200 1485 MALCOLM DONNA J 76 A ST 39,200 41,200 1202 BEAUDOIN RONALD & BRENDA, TSTS 77 A ST 294,600 303,000 1201 APONTE, KIMBERLY L 83 A ST 316,200 341,700 1483 TOWN OF DRACUT 88 A ST 112,000 117,600 1482 KRUGH KENNETH W. (JTRS) 90 A ST 290,200 312,800 1191 BAILEY PAUL R 92 A ST 303,000 309,400 1200 KIGGUNDU SEPIRIA (TE) 93 A ST 272,000 326,300 1199 FITZGERALD RAYMOND J.(TE) 95 A ST 275,300 296,800 1190 PROVOST ALAN MICHAEL 98 A ST 249,000 254,600 1198 DARES KIMBERLY JEAN IND. 101 A ST 277,300 302,800 11649 COGAN MICHAEL (TE) 104 A ST 284,700 306,700 997 MELLO JEFFREY A.