"Let's Keep Moving 2036" Freight Element

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map of Fairbanks

Goldstream...........15 Steese Highway 52 Sheep Emergency Dial.....911 N 23Õ Õ FAIRBANKS Murphy Dome.......25 18 28 25 58 29 Fox.........................12 24 The Golden Heart of Alaska Creek Rd. 13 Yukon River.........129 27 College Road Bridgewater Ave. Circle....................162 Points of Interest Kuskokwim CottonwoodTamarack 1. Fairbanks Convention & Visitors Bureau Willow Prudhoe Bay........487 Jack St. 2. Alaska Public Lands Information Center Jack St. Pine 16 Goldhill Hilling St. Creamers17 Lane 3. Borough Transit Bus Station Rd Bridgewater Dr. Ave. Chandalar Latoya Spruce 4. Westours/Gray Line of Alaska 22 Circle Caribou Way Capitol Ave. Õ Pioneer Way North Jack St. College Road Bridgewater Ave. 5. Alaska Railroad Depot Margaret Koyukuk Alaska Way Diane Marrieta Eleanor Esquire Ave. Bunnel Anna Vogel Ave. Blanch 6. Noel Wien Public Library 21 Hooper St. Mack Rd. Warren Harriet Kobuk Carr Ave. Andrew 7. Fairbanks Police /Fire departments Danby Road Sheenjek Yukon Dr. 37 Jarvis Kathryn Luke St. Cordwood Palmer St. Totem Dr. Rosella 8. Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Kantishna Drive Bonnie 35 Lutke St. Central Ave. O'connor Rd. Bridget Austin Maryleigh Suncha Cir. Copper Ln. Beaver Rd. Hayes Ave. Chinook 9. Growden Memorial Baseball Park Cottonwood St. Cottonwood Taku Dr. 42 31 Porchet Parks Highway Westwood Way Southern Ave Palace Circle UAF Farmers Loop Road 10. Alaskaland 50 Morgan Way Amber Ave. Princess Dr. Aurora Drive West Trainor Gate Road 11. Alaska State Troopers Nenana..................53 Salcha Shanley St. Dogwood St. Old Steese Highway 20 Lane Gloria Birch St. Antoinette Evergreen St. 12. Fairbanks International Airport Denali Park..........120 Alatna Dr. -

Conferences, Workshops, Seminars, Special Events

**Marks new items in this issue February 12, 2020 Compiled weekly by Peg Tileston on behalf of Trustees for Alaska, The Alaska Center, and The Alaska Conservation Foundation. CONFERENCES, WORKSHOPS, SEMINARS, SPECIAL EVENTS SPRING 2020 SUSTAINABLE ENERGY ONLINE CLASSES, BRISTOL BAY is offered through the UAF-Bristol Bay Sustainable Energy program. April 1 to April 29 - SMALL WIND ENERGY SYSTEMS, ENVI F150, 1-cr, 5 wks., 5:20 to 8pm, CRN 37949 May 8 – 10 - ENERGY EFFICIENT BUILDING DESIGN AND SIMULATION, ENVI F122, 1-cr 3 days, CRN TBD For more info contact Mark Masteller, Asst. Prof. Sustainable Energy, at 907-414-0198 or email [email protected]. February 20 – April 30 WASILLA - GARDENING CLASS SERIES will be held in the Wasilla Museum and Visitor Center from 6:30 to 8:30pm on the following dates: February 20 - Learn how to heal your landscape and create a cultivated ecology. We have been using regenerative theory in our home garden for a long time. We are applying regenerative theory to our Market Farm and the gains are enormous. March 5 - Explore Edible Landscaping for Alaska! This class provides simple and effective design tools on how to create growing spaces throughout your home layout. Using traditional landscaping techniques coupled with a Permaculture flair- learn how create, design and implement spaces that are both functional and beautiful. Taking our Permaculture Design for Growing Spaces is recommended but not required. March 19 - How to balance your soil so that you can reap the rewards of the spring sow. Learn all the regenerative practices for caring for your soil. -

Test Template 2010

THE Northern Brewer THE NEWSLETTER OF THE GREAT NORTHERN BREWERS CLUB OCTOBER 2013 The Prez Sez by Peter Hall his is the time for changes in the sea Tson, the club, and the beer we drink. The season is starting to get a little crispy, I guess you could say. I have had to scrape my windshield a The Prez Sez few times now. On a posi- tive note, the temperatures Secratary’s Corner in my home have stabi- lized. Instead of the summer sun coming in a running the temps up to as high as 80, my furnace keeps everything at a reasonable 67. Certainly seems like a good time to 2013 Celestial Mead brew a batch to me. Good temperatures and a new GNBC membership year loom Competition ahead. It is a great time to have some fresh homebrew to share. Be a Hero The club will, hopefully, have some new blood in the leadership very soon. The only thing I need is volunteers! Elections are upon us. We will have one more regular Vintage Beer Sale meeting before our official elections in November. I intend to run again, as does my VP and membership coordinator, Ross. Not running again are Tim, the Club Treasurer, More Beer Less Effort and Kat, the Club Secretary. I am running, but that certainly does not mean that I do not welcome any challengers. All four executive positions are up for a vote, as well as two of the board member positions. I really hope that we can have a real election this Fermento’s Shameless Plug time, so set up! I need names! If you have questions, send me an email at The Beer Up Here Application [email protected] and I will help however I can. -

AGDC Plan Template DRAFT 7Aug2012

ALASKA STAND ALONE PIPELINE/ASAP PROJECT DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan ASAP-22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 November 10, 2016 DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan REVISION HISTORY Approval Revision Date Comment Company Preparing AGDC Report 0 11/10/2016 Draft AGDC K Stevenson / M Thompson Document No: ASAP 22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 Date: November 10, 2016 Page ii NOTICE – THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY INFORMATION AND SHALL NOT BE DUPLICATED, DISTRIBUTED, DISCLOSED, SHARED OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE EXCEPT AS MAY BE AUTHORIZED BY AGDC IN WRITING. THIS DOCUMENT IS UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED. THIS COPY VALID ONLY AT THE TIME OF PRINTING DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADF&G Alaska Department of Fish and Game ADNR-PMC Alaska Department of Natural Resources – Plant Materials Center ADPOT&PF Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities AES ASRC Energy Services AGDC Alaska Gasline Development Corporation AKWAM Alaska Wetland Assessment Method AKLNG Alaska LNG ARR Alaska Railroad ASAP Alaska Stand Alone Pipeline ASA Aquatic Site Assessment ASRC Arctic Slope Regional Corporation CEQ Council on Environmental Quality CFR Code of Federal Regulations CMP Wetland Compensatory Mitigation Plan DA Department of the Army EED Environmental Evaluation Document ENSTAR EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency ERL Environmental, Regulatory, and Land FCI Functional Capacity Index FEIS Final Environmental Impact Statement ft Foot / feet GCF Gas Conditioning Facility HDD Horizontal directional drilling HGM hydrogeomorphic HUC Hydrologic Unit ILF in-lieu fee LEDPA Least Environmentally Damaging Practicable Alternative Mat-Su Matanuska-Susitna MSB Matanuska-Susitna Borough Document No: ASAP 22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 Date: November 10, 2016 Page iii NOTICE – THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY INFORMATION AND SHALL NOT BE DUPLICATED, DISTRIBUTED, DISCLOSED, SHARED OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE EXCEPT AS MAY BE AUTHORIZED BY AGDC IN WRITING. -

Please Call TOWER ROCK LODGE When You Arrive in Anchorage 1

Please Call TOWER ROCK LODGE What is included? When You Arrive in Anchorage All necessary equipment including all tackle, bait, flies, Orvis #8 fly rods 1-800-284-3474 and spinning gear and Loomis salmon rods with Shimano Dakota reels. GRUDGEON rain gear and Orvis hip Destination Kenai Peninsula waders Secluded bank fishing in front of Situated near the town of Soldotna, in Tower Rock Lodge for Silvers and south-central Alaska, TOWER ROCK LODGE Reds. Excellent opportunities. 1 800 284 FISH (3474) is an internationally One 50 # wet lock box for your recognized five star full service lodge catch, for most package plans located 12 miles upriver on the banks of the All meals (advance notice for special world famous Kenai River. Upon arrival, dietary needs please) and please check in at the Orvis Dining Hall. complimentary beverages and wine Arriving in Anchorage Check YOUR Checklist! Drive from Anchorage airport 147 You will need to obtain your fishing miles (3-1/2 hours) along the scenic license and King Salmon stamp (if Seward Highway thru the Chugach applicable) covering the amount of Mountains to the town of Soldotna days you plan to fish (1, 3, 7, 14 days and TOWER ROCK LODGE and annually). Fly EVA Aviation 800 478 1947 www.admin.adfg.state.ak.us/license/ www.flyera.com to Kenai Airport or at any local convenience store. (flight time 25 minutes), pick up Plan your clothing around a layering your rental car and drive directly to system that adjusts to changing TOWER ROCK LODGE which is only temps and conditions. -

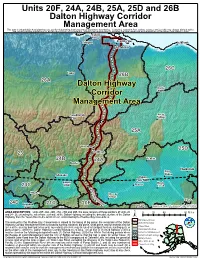

Dalton Highway Corridor Management Area ! This Map Is Intended for Hunt Planning Use, Not for Determining Legal Property Or Regulatory Boundaries

Units 20F, 24A, 24B, 25A, 25D and 26B Dalton Highway Corridor Management Area ! This map is intended for hunt planning use, not for determining legal property or regulatory boundaries. Content is compiled from various sources and is subject to change without notice. See current hunting regulations for written descriptions of boundaries. Hunters are responsible for knowing the land ownership and regulations of the areas they intend to hunt. Colville ! Village Prudhoe Bay Nuiqsut ! Kaktovik ! ! ! Deadhorse 26C Umiat ! 26B 26A Dalton Highway Arctic Corridor NWR Management Area Anaktuvuk Arctic Pass Village ! ! 25A Wiseman ! 25D 23 ! Coldfoot Venetie ! 24B 24A ! Bettles ! Chalkyitsik Fort ! Yukon Allakaket ! ! Yukon Arctic Circle Flats NWR Kanuti Birch 24C NWR ! Beaver Creek D ! A L T Hughes O ! N Stevens Village H ! IG H Circle W ! ! 24D Koyukuk 21C 20F AY NWR 20F 25C Sources: Esri, DeLorme, USGS,25B NPS AREA DESCRIPTION: Units 20F, 24A, 24B, 25A, 25D and 26B, the area consists of those portions of Units 20 0 20 40 ! 80 Miles and 24 - 26 extending five miles from each side of the Dalton Highway, including the driveable surface of the Dalton ! ± Highway, from the Yukon River to the Arctic Ocean, and including the Prudhoe Bay Closed Area. Management Area The area within the Prudhoe Bay Closed Area is closed to the taking of big game; the remainder of the Dalton Subunit Boundary Highway Corridor Management Area is closed to hunting; however, big game, small game, and fur animals may be Closed Area taken in the area by bow and arrow only; no -

Trends in Alaska's Mineral Industry

I C bureau of mines information circular 8045 TRENDS IN ALASKA'S MINERAL INDUSTRY By Alvin Kaufman UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF MINES 1961 I TRENDS IN ALASKA'S MINERAL INDUSTRY By Alvin Kaufman * * * * + * * * * * 4 information circular 8045 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES Marling J. Ankeny, Director This publication has been cataloged as follows: Kaufman, Alvin Trends in Alaska's mineral industry. [Washington] U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Mines [1961] ii, 43 p. illus., tables. 26 cm. (U.S. Bureau of Mines. Information circular 8045) Bibliographical footnotes. 1. Mineral industries - Alaska. I. Title. (Series) TN23.U71 no. 8045 622.06173 U.S. Dept. of the Int. Library. CONTENTS Page Introduction and summary ...................................... 1 Acknowledgments. ............................................ 5 The country and its problems ............ .... ........ 5 The country ....................... .........................5 The problems..................................... .... 6 Comparison with other areas................................... 10 The Alaskan economy and the mineral industry.................. 14 The future economy and its mineral needs................. 14 Taxes and the mineral industry.......................... 21 Foreign imports, exports, and the mineral industry....... 30 The future mineral industry ......... ......................... 31 Fuels .................................................... 35 Metals .................................................. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:10-cv-02076-EGS Document 35 Filed 06/10/11 Page 1 of 25 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) NORTHERN AIR CARGO, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE, ) Civil Action No. 10-2076 (EGS) ) Defendant, ) ) and ) ) PENINSULA AIRWAYS, INC., ) ) Defendant-Intervenor. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION On December 3, 2010, the United States Postal Service (the “Postal Service”) granted an equitable tender of nonpriority mainline bypass mail to Peninsula Airways, Inc. (“PenAir”) on five mainline routes in rural Alaska pursuant to 39 U.S.C. § 5402(g)(5)(c) (“§ 5402(g)(5)(C)”). This equitable tender is now being challenged by three mainline carriers – Northern Air Cargo (“NAC”), Tatonduk Outfitters Ltd d/b/a Everts Air Cargo (“Everts”), and Lynden Air Cargo LLC (“Lynden”) (collectively, “plaintiffs”). Specifically, plaintiffs challenge the Postal Service’s purportedly ultra vires determination that PenAir had satisfied the “Prior Service and Capacity Requirement” of 39 U.S.C. § 5402(g)(1)(A)(iv)(II) (“§ 5402(g)(1)(A)(iv)(II)”) as of Case 1:10-cv-02076-EGS Document 35 Filed 06/10/11 Page 2 of 25 December 3, 2010.1 Plaintiffs seek both declaratory and injunctive relief. See generally Compl. Pending before the Court is plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment, as well as the cross-motions for summary judgment filed by Defendant Postal Service and Defendant-Intervenor PenAir (collectively, “defendants”). Upon consideration of the motions, the responses and replies thereto, the applicable law, the entire record, and for the following reasons, the Court hereby DENIES plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment and GRANTS defendants’ cross-motions for summary judgment. -

CS PRP Notification Template

Department of Environmental Conservation SPILL PREVENTION & RESPONSE Contaminated Sites Program 610 University Avenue Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Main: 907.451.2143 Fax: 907.451.2155 www.dec.alaska.gov File: 240.38.010 4 April 2019 Kristin Hess Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Mining Land and Water Management 550 W. 7th Ave., Suite 1070 Anchorage, AK 99501 Re: ADOT&PF Glenn Highway Maintenance Camp, Mile 185 Glenn Highway Hazard ID: 3347 ** STATE OF ALASKA NOTIFICATION – HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE LIABILITY** Dear Ms. Hess: This notification letter is to advise you of your agency’s liability for the contamination identified at the ADOT&PF Glenn Highway Maintenance Camp site located at mile 185 Glenn Highway, near Glenn Allen, Alaska. Alaska Statute (AS) Title 46 authorizes the State to respond to this pollution incident and to take appropriate action to minimize potential damage to human health, safety or welfare or to the environment. Under Title 46, any Responsible Party may be held financially responsible for any actions taken by the State. AS 46.03.822 (Strict Liability for the Release of Hazardous Substances) establishes who is financially responsible or liable for the investigation and cleanup of any release or threatened release of a hazardous substance. State records indicate that you meet one or more of the following criteria: • __ owned or controlled the hazardous substance at the time of its release; • X own(ed) or operate(d) the property or facility from which the release occurred; • X own or operate the property at which the hazardous substance came to be located; or • __ arranged for transport, disposal or treatment of hazardous substances that were released. -

Essential Fish Habitat Assessment

Essential Fish Habitat Assessment Prepared for: State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities and Prepared by: HDR Alaska, Inc. 2525 C Street, Suite 305 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 February 2013 Project No. 53014 Sterling Highway Mile 45 to 60 Draft SEIS Essential Fish Habitat Assessment Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities February 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Section 2 Project Description ................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 Project Area ............................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Proposed Action ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 Reasonable Alternatives ......................................................................................................... 2 2.3.1 No Build Alternative .............................................................................................. 3 2.3.2 Cooper Creek Alternative ...................................................................................... 3 2.3.3 G South Alternative ............................................................................................... 4 2.3.4 Juneau Creek Alternative ...................................................................................... -

Alaska Seafood Industry Economic Importance Alaska’S Seafood Industry Is World-Scale

Some of the Most Important Things to Know About the Economy of Alaska by Gunnar Knapp Professor of Economics Institute of Social and Economic Research University of Alaska Anchorage April 2007 Subsistence salmon Subsistence drying Subsistence--Alaska’s original economy--remains an important part of the economy of rural Alaska. People in rural Alaska get much of their food from subsistence. Subsistence is a vital part of Alaska Native culture. Subsistence faces challenges, including a limited resource base and growing demands from sport and commercial users. An important debate has been going on for many years over who should have the right to participate in subsistence, and the relative roles the federal and state governments should have in managing subsistence resources. How important is subsistence? Annual Approximate subsistence cost of buying harvest per the food in a Area of Alaska person (lbs) store Northern, $2,064- Western & 516-774 lbs $2,656 Interior Alaska A woman at a subsistence “fish camp”—an important Anchorage & 16-35 lbs $64-$140 Fairbanks Subsistence harvesting part of summer family life in of Beluga whales much of village Alaska The Rural Alaska Economy The economy of rural Alaska—particularly villages in western and interior Alaska—is very different from that of urban areas that account for most of Alaska’s population. These population of “village Alaska” is overwhelmingly Alaska Native. Residents get much of their food from subsistence. Costs are very high, and basic infrastructure such as housing and water are far below the standards of urban Alaska. There are few jobs, and a very high share of jobs are in local government, education and health care. -

Dalton Highway Mile Markers

Dalton Highway Mile Markers To calculate distances from Fairbanks, add 83 miles to the Dalton Mileposts 56 Mile Yukon River 175.2 Mile Slate Creek 60.5 Mile Hot Spot Café 176 Mile Clara Creek 61.8 Mile Seven Mile Camp 179.9 Mile Marion Creek 70.4 Mile Ray River 187.2 Mile Minnie Creek 72.5 Mile Fort Hamlin Hills Creek 188.5 Mile Wiseman Rd 79.1 Mile No Name Creek 190 Mile Hammond River 82 Mile 82 Mile Material Site 196 Mile Sheep Creek 88 Mile Overlook & Material Site (not marked) 197 Mile Gold Creek 88.5 Mile Mackey Hill 198 Mile Linda Creek 93 Mile Dall River 204.2 Mile Sukakpak Mountain 94 Mile Whimbrel Hill - 94 Mile MS 209.3 Mile Dietrich Camp 98 Mile Finger Mountain 211 Mile Disaster Creek 105.4 Mile Kanuti River 224 Mile Material Site 107-1A 107 Mile Old Man Camp 228.2 Mile Nutirwik Creek 114 Mile Fish Creek 234.1 Mile North Slope Borough boundary 115.2 Mile Arctic Circle 235 Mile Chandalar Outhouse 124.7 Mile South Fork Bonanza 239.2 Mile Chandalar House/DOT 125.4 Mile North Fork Bonanza 244.8 Mile Atigun Pass bottom southside 127 Mile Material Site 90-1 246.8 Mile Atigun Pass top 129 Mile Material Site 90-2 249.6 Mile Spike Creek 132 Mile Gobbler's Knob 253.7 Mile Atigun River 134 Mile Prospect Creek 259 Mile Trevor Creek 136 Mile Prospect Creek Camp (Road to Bettles) 265.5 Mile Roche Moutonee Creek 137.1 Mile Pump Station #5 267.8 Mile Holden Creek 138 Mile Jim River DOT 269.3 Mile Pump Station #4 139 Mile Material Site 91-3 275 Mile Galbraith Lake 140.1 Mile Jim River I 278 Mile Island Lake 141 Mile Jim River II 284.2 Mile Toolik Field Station / Lake 141.3 Mile Douglas Creek 288 Mile Horizon Lake 144.1 Mile Jim River III 299.1 Mile N.