Biscuits, Hard Tack, and Crackers in Early America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Granny White

Granny White Granny White's Special Edition Yeast Bread Recipes Over 230 Mouthwatering Yeast Bread Recipes 1 Granny White Thank You For your purchase of the "Granny White's Special Edition Yeast Bread Cookbook" from Granny White's Cooking Delites! http://www.grannywhitescookingdelites.com Copyright 2003@Charles E. White 2 Granny White Dedication: This New Granny White's "Special Edition" Bread Cookbook is dedicated to Scott and Tiffany Fielder. Married March 02, 2003. Congratulations ! 3 Granny White contents.....just click the recipe you want to see and you will automatically go to that page. BREADS MADE WITH YEAST 4−H Champion Bread Quick and Easy Anadama Bread Pain Juif a l'Anis Italian Anise Bread Apple Breakfast Loaf Apple Oatmeal Bread Apple Pull Apart Bread Apricot−Wheat Bread Absolutely Apricot Bread Arabian Bread−Ka'kat Arabic Bread The Basic Bagel Recipe Bagels with Seeds New York Style Bagels Fat Free Bagels Sourdough Bagels Sesame Seed Bagels Cinnamon Blueberry Bagels Barbari Bread (Nan−e Barbari) Barley Bread Beer Cheese Bread Beer Bread New York Bialy's Bible Bread from Ezekeil 4:9 4 Granny White Angel Biscuits Yeast Biscuits Biscuits Angel Biscuits (No Rising Necessary) Deluxe Buttermilk Biscuits Sourdough Biscuits Black Bun Russian Black Bread Black Bread Finnish Black Bread (Hapanleipa) Ukrainian Black Bread Bran Molasses Sunflower Bread Olive oil and fennel bread sticks Italian Bread Sticks Brioche Brown Nut Bread Brown Rolls Brown Bread Buckwheat Walnut Bread Candy Cane Bread Gooey Caramel Rolls Unyeasted Carrot Rye -

Download Recipe Book

together we BRUNCH Curbside Delivery Easy ecipes tailed f take-out! 1 #Together WeBrunch Even though we can’t be together, Contents we can still brunch together! To Contents help support foodservice operators during this time, we’ve created a Deluxe Pancake Strata ................. 3 recipe book full of ideas perfect for delivery and takeout. These menu Baked French toast ...................... 4 suggestions are low skill, low labor Blueberry Pancake Squares ......... 5 and can easily be made ahead of time. Package and sell hot for individual Sticky buns .................. 6 carryout, as refrigerated grab ‘n go options, or even as limited bakery Garlic Cheese Biscuits ...................7 sales. Enjoy the recipes—and Biscuit Bread Pudding ................... 8 thank you for all that you do! Flat parfait ................................... 9 EASY ENTRÉES • SAVORY SIDE DISHES BASIC BAKESHOP • DELICIOUS DESSERTS Yogurt Mousse ............................. 10 SIMPLE REFRESHMENTS More Recipes ..................................11 Deluxe Pancake Strata 54 servings • 32" full hotel pans or 9 – 8 x 8" foil pans INGREDIENTS WEIGHT MEASURE VEGETABLES Vegetable oil 2 oz 1/4 cup Onions, diced 2 lb 4 cups Green bell peppers, fresh, diced 1 lb 3 cups Red bell peppers, fresh, diced 1 lb 3 cups ASSEMBLY Water, cool approx. 72°F 5 lb 8 oz 11 cups Gold Medal™ Complete Buttermilk Pancake Mix (11827) 5 lb 1 box Ham, diced 2 lb 6 cups Cheddar cheese, shredded 2 lb 8 cups SERVING Salsa 1 lb 11 oz 3 cups DIRECTIONS VEGETABLES 1. Heat oil in sauté pan; add onions and peppers and cook over medium heat for 5 minutes. 2. Set aside to cool. METHOD TEMP TIME ASSEMBLY Convection Oven* 350°F 15-20 minutes 1. -

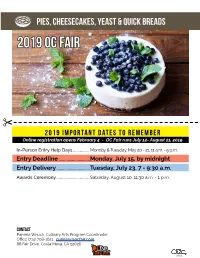

2019 OC Fair

Pies, Cheesecakes, Yeast & Quick Breads 2019 OC Fair 2019 IMPORTANT DATES to remember Online registration opens February 4 - OC Fair runs July 12- August 11, 2019 In-Person Entry Help Days ....................Monday & Tuesday, May 20 - 21, 11 a.m. - 5 p.m. Entry Deadline ............................Monday, July 15, by midnight Entry Delivery ..............................Tuesday, July 23, 7 - 9:30 a.m. Awards Ceremony .......................................Saturday, August 10, 11:30 a.m. - 1 p.m. CONTACT Pamela Wnuck, Culinary Arts Program Coordinator Office (714) 708-1621 [email protected] 88 Fair Drive, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 2019 Pies, Cheesecakes, Yeast & Quick Breads TABLE OF CONTENTS Rules ............................................................................................................................... 1 Eligibility / Entry Limit / Exhibitor Ticket ............................................2 How to Enter / Help with Entering ..........................................................3 Entry Delivery ...........................................................................................................4 Judging .........................................................................................................................5 Awards / Awards Ceremony ........................................................................6 Adult Divisions ...................................................................................................... 7-9 Division 1060 Quick Breads Division 1061 Muffins, Biscuits & Scones -

SUMMARY We Use Only the Highest Quality Pressed Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Canola Oils— No Hydrogenated Oils

Pitchoun! makes you a promess: be your premium ally for a succesful event with amazing food sprinkled by stylish presentation! From baby showers to business meetings, weddings to casual work lunches, Pitchoun! has everything you need to help make your next event a tasty hit! We use our french ‘savoir-faire’ to bake your catering! Everything is hand-made daily on site by our baking and pastry team using only fresh produce from local farms, sustainable & organic ingredients and with no GMOs neither preservatives. Our meat and poultry are antibiotic, hormone and nitrate-free. Our eggs are free-range and pasture raised. SUMMARY We use only the highest quality pressed extra virgin olive oil and canola oils— no hydrogenated oils. We offer organic beverages, coffees and teas. Bread p3 Breakfast - sweets p5 Bon Appétit ! Breakfast - savory p7 Sweet Bites p9 Cakes & Tarts p11 Savory Bites p17 • 24 to 48 hour notice minimum Sandwiches p21 • Pick-up ($50 minimum) or delivery ($100 minimum + delivery fee) Salads p23 • Time of pick-up/delivery must be specified at the order; everything is fresh and Lunch Boxes p24 made to order Drinks p25 • You may mix with our retail menu • Finger bites are served on fancy disposable black trays, ready to be served to Gifts p26 your guests, or in catering boxes for the rest • Payment is required at the order, except for events & large cakes planned in advance with 50% at order + 50% paid 2 weeks before pick-up or delivery • Orders, changes and cancellations must be made at least 48 hours in advance (except for events -

Harrow Road Café

Meals served from 8:30 AM – 4 PM EST HISTORIC RUGBY’S HARROW ROAD CAFÉ O Happy Day Neighbor! ~~~ Good Morning! 9am – 11am Cafe Frittata Crust free egg pie and a side of fruit. Ask your server for today’s fresh ingredients. 9.95 Pioneer Breakfast Platter two eggs, three slices of bacon or two sausage patties, house made biscuit with white gravy or Pullman’s Loaf toast, roasted potatoes and sliced tomato. 9.95 Percy Cottage Pancakes large stack with bacon or sausage and fresh fruit. 8.95 Maggie’s Nosh two eggs, Pullman’s Loaf toast and sliced tomato. 4.95 Afternoon Meal! 11am – 4pm Sunday Roast 1st Sunday ~ fried shrimp with house cocktail sauce 2nd Sunday ~ house made meatloaf 3rd Sunday – spicy fried chicken and waffles with muddy pond sorghum gravy 4th Sunday – open faced pot roast sandwich our Sunday Roast is served with mashed potatoes, daily vegetable and a side salad. 12.95 Shepherd’s Pie seasoned pot roast with green peas, carrots, celery, and onion, simmered in a house made sauce, topped with mashed potatoes and served with a side salad. 11.95 Rugby Burger 8 oz of fresh ground round with Cheddar or Swiss, served on a Kaiser Roll, along with fries or fruit. 10.95 Ploughman’s Lunch rye bread and sweet-churned butter, Muddy Pond cheese, pickled okra, dark mustard and thick sliced Virginia style ham. 10.95 Harrow Road House Salad mixed Romaine and Green Leaf lettuces, grated carrots and cucumbers, tomatoes, shredded cheddar and roasted chickpeas. 4.95 Dressings: Dijon Vinaigrette, Italian, 1000 Island Grilled Chicken Salad tender, marinated grilled chicken, mixed Romaine and Green Leaf lettuces, grated carrots and cucumbers, tomatoes, shredded cheddar and roasted chickpeas. -

A Taste of Food in the Civil War

Ellie Schweiker Jolene Onorati Manning school A Taste of Food in the Civil War What’s the way to keep a soldier alive? Strategy? Weaponry? Medicine? Or is it something as basic as food? While many of us take our meals for granted, the Civil War was impacted by the distribution and intake of food. Contrary to popular belief, most Union soldiers had plenty of food. The restrictions experienced by both the Union and Confederate soldiers were the types of food available during the civil war. The army with the soldiers well nourished gained an advantage. Societal norms regarding who prepared the food was also a factor and differed between slave states and free states. Without kitchens with experienced chefs or slaves, soldiers had to cope with the unvaried and insufficient rations they received. As the war began, Union soldiers started to realize the bleak reality of the food they were given. The United States Sanitary Commission, also known as Sanitary, supported and supervised all food allocation in the North. Captain James Sanderson was a notable volunteer who worked for the Sanitary. He noticed the importance of food in a man’s body and how advantageous an ablebodied man can be. After authoring the first cookbook distributed to soldiers, Sanderson helped raise awareness about meals on the battlefield. In Sanderson’s cookbook it was evident he was passionate about soldiers’ nutrition on the battlefield. “Remember that beans, badly boiled, kill more than bullets; and fat is more fatal than powder. In cooking, more than in anything else in this world, always make haste slowly. -

Classic American Dinner Rolls Can Never Go out of Style

Classic American Dinner Rolls A trio of traditional shapes from a light and buttery yeast dough Use a dough cutter to cut equal pieces. Here, the BY RANDALL PRICE author cuts portioned dough into 36 pieces. He’ll roll them into balls and then cluster these together to make cloverleaf rolls. Cloverleaf rolls keep their shape in a muffin tin. Form the rolls by putting three balls of dough into each cup, and then let the rolls rise in the pan. Photos except where noted: Martha Holmberg Copyright © 1994 - 2007 The Taunton Press readmaking is one of the kitchen’s miracles. BFew other activities bring such satisfaction to the cook, or such pleasure to the guests. While current baking trends favor hearty, rustic breads, classic American dinner rolls can never go out of style. The warmth of a piping-hot, homemade dinner roll, topped with a cool slice of sweet butter, is a very special treat. And while specialty bakeries can sometimes create very high-quality breads, the only way you can savor soft, fresh dinner rolls is by taking the time to make them yourself. Fortunately, melt-in-your-mouth dinner rolls are easy to make from scratch. The rich dough is a delight to knead, and the forming of the basic shapes requires no special skills other than a degree of accuracy in rolling, cutting, and portioning. ROLL DOUGH IS NOT BREAD DOUGH I think a slightly sweet, rich, white-flour dough gives the best results. In my recipe, butter and egg yolk give richness, while whole milk and oil provide tenderness. -

Ship's Biscuit Recipe

Ship’s Biscuit Ship’s biscuit was a hard piece of bread that Constitution’s sailors ate at nearly every meal. The biscuit was baked on land, stored on board the ship, and then sent out to sea with the sailors. Sailors soaked the rock-hard biscuit in their stew to soften it before taking a bite. If you bake a ship’s biscuit and would like to taste it, make sure you follow the sailors’ example and soak it in water or stew before eating! Ingredients 2 cups stone ground whole wheat flour wooden mallet or rolling pin ½ teaspoon salt greased baking sheet ½ cup water lightly floured work surface Directions 1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit 2. Combine flour and salt on work surface. 3. Add the water. 4. Beat with mallet or rolling pin until ½ inch thick. 5. Fold and repeat several times. 6. Cut the dough into cookie-sized pieces. 7. Place on baking sheet and cook for 30 minutes. Serves 5, at 5-inch round biscuits. a History Note William Burney, in A New Universal Dictionary of the Marine (London, T. Cadell & W. Davies: 1815), gives the best description of the process of making ship’s biscuit: The process of biscuit-making for the navy is simple and ingenious, and is nearly as follows. A large lump of dough, consisting merely of flower and water, is mixed up together, and placed exactly in the centre of a raised platform, where a man sits upon a machine, called a horse, and literally rides up and down throughout its whole circular direction, till the dough is equally indented, and this is repeated till the dough is sufficiently kneaded. -

Homemade Yeast Bread Susan Z

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950 SDSU Extension 11-1933 Homemade Yeast Bread Susan Z. Wilder Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ Recommended Citation Wilder, Susan Z., "Homemade Yeast Bread" (1933). Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950. Paper 337. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_circ/337 This Circular is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cooperative Extension Circulars: 1917-1950 by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Extension Circular 338 November, 1933 ( Homemade Yeast Bread By Susan Z. Wilder Extension Nutritionist and Supervisor, Home Extension Work Each homemaker will have to decide whether it is economy for her to bake or buy bread. The fancy breads from the bakery are more expensive than the plain bread. They can be made with very little more time than that required to make plain bread. To determine the cost of making it 'is necessary to keep a record of the cost of the ingredients and fuel. The difference between this and the value of the finished product figured at market price will give the amount saved. At present prices about one-half ii the cost can be saved on plain bread and more than half on fancy breads. t Time has not been considered in this estimate of saving. -

All American Breakfast OUR SENIOR CITIZEN FRIENDS MAY RECEIVE 10% OFF THEIR ENTIRE BREAKFAST ORDER

All American Breakfast OUR SENIOR CITIZEN FRIENDS MAY RECEIVE 10% OFF THEIR ENTIRE BREAKFAST ORDER. PLEASE INFORM THE CASHIER. GIANT COUNTRY BREAKFAST Choose one from each column: Scrambled Eggs (3) Bacon (4) Biscuit & Gravy Spicy Potatoes Scrambled Country Omelet (3) Sausage (2) (Pork or Turkey) Toast Mild Potatoes Scrambled Eggs and Sausage (3) Ham Steak English Muffin Hash Browns Eggs (Any Style) (3) Pork Chop (1) Biscuit Grits Chicken Fried Steak Pancake (1) Fresh Fruit Sirloin Strip (add $2.29) $9 .80 A HEARTY FAVORITE Choose one from each column: Scrambled Eggs (2) Bacon (4) Biscuit Spicy Potatoes Scrambled Country Omelet (2) Sausage (2) (Pork or Turkey) English Muffin Mild Potatoes Scrambled Eggs and Sausage (2) Ham Steak Toast Hash Browns Eggs (Any Style) (2) Pork Chop (1) Biscuit & Gravy (add 59¢) Grits Chicken Fried Steak Pancake (1) Fresh Fruit Sirloin Strip (add $2.29) $8 .80 THE TRADITIONAL Choose one from each column: Scrambled Eggs (2) Bacon (4) Biscuit Scrambled Country Omelet (2) Sausage (2) (Pork or Turkey) English Muffin Scrambled Eggs and Sausage (2) Ham Steak Toast Eggs (Any Style) (2) Pork Chop (1) Pancake (1) Chicken Fried Steak French Toast (1) Sirloin Strip (add $2.29) Biscuit & Gravy (add 59¢) $7 .99 BARGAIN BASEMENT SPECIAL Choose one from each column: Scrambled Eggs (2) Biscuit Spicy Potatoes Scrambled Country Omelet (2) English Muffin Mild Potatoes Scrambled Eggs and Sausage (2) Toast Hash Browns Eggs (Any Style) (2) Biscuit & Gravy (add 59¢) Grits $6 .99 Fresh Fruit 05-20 Pancakes, Waffles, Biscuits, etc. Pancake Special . 7 .99 Stack of 3 cakes served with Bacon, Sausage (Pork or Turkey) or Ham Stuff them with Sausage, Chocolate Chips, Pecans or blueberries ................... -

Hardtack – a Cowboy’S Snack

Hardtack – A Cowboy’s Snack It has often been said that “an army marches on its stomach”, showing the importance of staying well supplied and fed. The same could be said of the cowboy and the need for those men riding in the saddle to stay well fed while they made their way up the trail. While at the end of a hard days ride the cowboy would have a chance to fill their stomach when they were able to stop for the night and gather around the chuck wagon for dinner, during the days work there weren’t many chances to stop and take a snack break. If the cowboy wanted to eat something while on their horse working, it required something that was easily carried and could stand up to the stress of the trail. For many a snack, the cowboy turned to a traditional food item that had served many an explorer and soldier alike for a few hundred years…the hardtack cracker. Hardtack: Not quite bread, note quite a biscuit While not sounding very appetizing, hardtack has been found in many a pocket and knapsack throughout history. Having been around since the Crusades, the version of hardtack most commonly found on the American frontier was created in 1801 by Josiah Bent. Bent called his creation a “water cracker” that contained only two ingredients, water and flour. These ingredients would then be mixed into a paste, rolled out, cut into squares, and finally baked. Once the cooking process was over, you’d be left with a dry cracker that would stand up to the elements for a long time, while also not being the most appetizing snack. -

Army Hardtack Recipe

Army Hardtack Recipe Ingredients: •4 cups flour (preferably whole wheat) •4 teaspoons salt •Water (about 2 cups) Preheat oven to 375 degrees. Mix the flour and salt together in a bowl. Add just enough water (less than two cups, so that the mixture will stick together, producing a dough that won’t stick to hands. Mix the dough by hand. Roll the dough out, shaping it roughly into a rectangle. Cut the dough into squares about 3 x 3 inches and ½ inch thick. After cutting the squares, press a pattern of four rows of four holes into each square, using a nail, or other such object. Do not punch all the way through the dough. It should resemble a modern saltine cracker. Turn the square over and do the same to the other side. Place the squares on an ungreased cookie sheet in the oven and bake for 30 minutes. Turn each piece over and bake for another 30 minutes. The crackers should be slightly brown on both sides. Makes about 10 squares. This legendary cracker, consisting of flour, water, and salt, was the main staple of the soldier’s diet. If kept dry, it could be preserved almost indefinitely. Before a campaign, troops were typically issued three day’s worth of rations, including thirty pieces of hardtack. Hardtack was sometimes jokingly referred to as “tooth dullers” or “sheet iron”. The preferred way to prepare hardtack was to soften them in water, and then fry them in bacon grease. However, on the march, soldiers ate them “raw” with a piece of salt pork, bacon, or some sugar.