Solti's Ring Remastered: Ascent to Valhalla Or Descent Into Nibelheim?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

By Richard Wagner 1856 Ride of the Valkyries

KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER: KEY PIECES OF MUSIC 6 BY RICHARD RIDE WAGNER OF THE 1856 VALKYRIES THE STORY—well, a short snippet of it... Wotan has 9 daughters. These are the Valkyries whose task it is to recover heroes fallen in battle and bring them back to Valhalla where they will protect Wotan’s fortress. Wotan hopes for a hero who will take a ring from the dragon. Wotan has two other children who live on Earth; twins called Siegmund and Sieglinde. They grow up separately but meet one day. Siegmund plans to battle Sieglinde’s husband as she claims he forced her to marry him. Wotan believes Siegmund wants to capture and keep the ring and won’t protect him. He sends one of his Valkyrie daughters to bring him to Valhalla but he refuses to go without his sister. She tries to help him in battle against her father’s wishes but sadly he dies. Meanwhile, the Valkyries congregate on the mountain-top, each carrying a dead hero and chattering excitedly when the daughter arrives with Sieglinde. Wotan is furious and plans to punish her. Prelude An introductory piece of music. A prelude often opens an act in an opera Act A musical, play or opera is often split into acts. There is often an interval between acts THE MUSIC THE COMPOSER Ride of the Valkyries is only part of a Wagner loved the brass section and even huge major work. It is taken from a cycle invented the Wagner Tuba which looks like of 4 massive operas known as The Ring a cross between a French horn and of the Nibelungs or The Ring for short. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

05-09-2019 Siegfried Eve.Indd

Synopsis Act I Mythical times. In his cave in the forest, the dwarf Mime forges a sword for his foster son Siegfried. He hates Siegfried but hopes that the youth will kill the dragon Fafner, who guards the Nibelungs’ treasure, so that Mime can take the all-powerful ring from him. Siegfried arrives and smashes the new sword, raging at Mime’s incompetence. Having realized that he can’t be the dwarf’s son, as there is no physical resemblance between them, he demands to know who his parents were. For the first time, Mime tells Siegfried how he found his mother, Sieglinde, in the woods, who died giving birth to him. When he shows Siegfried the fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, Siegfried orders Mime to repair it for him and storms out. As Mime sinks down in despair, a stranger enters. It is Wotan, lord of the gods, in human disguise as the Wanderer. He challenges the fearful Mime to a riddle competition, in which the loser forfeits his head. The Wanderer easily answers Mime’s three questions about the Nibelungs, the giants, and the gods. Mime, in turn, knows the answers to the traveler’s first two questions but gives up in terror when asked who will repair the sword Nothung. The Wanderer admonishes Mime for inquiring about faraway matters when he knows nothing about what closely concerns him. Then he departs, leaving the dwarf’s head to “him who knows no fear” and who will re-forge the magic blade. When Siegfried returns demanding his father’s sword, Mime tells him that he can’t repair it. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Strauss Elektra Solti SC

Richard Strauss Elektra Elektra: Birgit Nilsson; Klytemnestra: Regina Resnik; Chrysothemis: Marie Collier; Oreste: Tom Krause; Aegistheus: Gerhard Stolze Vienna State Opera Chorus and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Georg Solti Recorded June, September and November 1966 at the Sofiensaal, Vienna Recording Engineers: Gordon Parry and James Brown Producers: John Culshaw and Christopher Raeburn Remastered at Air Studios London by Tony Hawkins and Ray Staff Speakers Corner 2LPs Decca SET 354/5 Performance: 5 Strauss's Elektra was premièred in 1909 and marks the highpoint of the composers operatic career. Never again would he compose such searingly dramatic, concise music, replete with startlingly vivid orchestration, and a wealth of highly chromatic (and often atonal) thematic material, centred around decidedly Wagnerian sounding leitmotifs. It is isn't easy to cast. The title role needs a true dramatic soprano who is happy above the stave, and that of Klytemnestra a big-voiced mezzo- soprano. Chrysothemis is written for a lyric soprano, and Oreste for an heroic baritone. Elektra's don't come any better than Birgit Nilsson. She was 48 when the recording was made, and even the most exposed leaps and murderously high tessitura don't bother her. As the greatest Wagnerian soprano since Frieda Leider, she can effortlessly ride the orchestra, while still using a wide dynamic range in quieter passages. There are occasions when her intonation falters in the Recognition Scene, but this is a classic, thrillingly savage performance. Regina Resnik scales the same dramatic heights as Nilsson in her confrontation with Elektra, and her laughter at the end of the scene is gloriously OTT. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

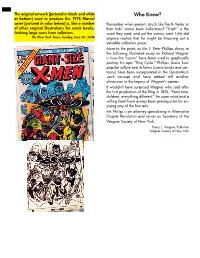

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Media Draft Appendix

Media Draft Appendix October, 2001 P C Hariharan Media Historical evidence for written records dates from about the middle of the third millennium BC. The writing is on media1 like a rock face, cave wall, clay tablets, papyrus scrolls and metallic discs. Writing, which was at first logographic, went through various stages such as ideography, polyphonic syllabary, monophonic syllabary and the very condensed alphabetic systems used by the major European languages today. The choice of the medium on which the writing was done has played a significant part in the development of writing. Thus, the Egyptians used hieroglyphic symbols for monumental and epigraphic writing, but began to adopt the slightly different hieratic form of it on papyri where it coexisted with hieroglyphics. Later, demotic was derived from hieratic for more popular uses. In writing systems based on the Greek and Roman alphabet, monumental writing made minimal use of uncials and there was often no space between words; a soft surface, and a stylus one does not have to hammer on, are conducive to cursive writing. Early scribes did not have a wide choice of media or writing instruments. Charcoal, pigments derived from mineral ores, awls and chisels have all been used on hard media. Cuneiform writing on clay tablets, and Egyptian hieroglyphic and hieratic writing on papyrus scrolls, permitted the use of a stylus made from reeds. These could be shaped and kept in writing trim by the scribe, and the knowledge and skill needed for their use was a cherished skill often as valuable as the knowledge of writing itself. -

Dual Digital Audio Tape Deck OWNER's MANUAL

» DA-302 Dual Digital Audio Tape Deck OWNER’S MANUAL D00313200A Important Safety Precautions CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALI- Ü FIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol, within equilateral triangle, is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product’s enclosure ÿ that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the pres- ence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature Ÿ accompanying the appliance. This appliance has a serial number located on the rear panel. Please record the model number and WARNING: TO PREVENT FIRE OR SHOCK serial number and retain them for your records. Model number HAZARD, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS Serial number APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. For U.S.A Important (for U.K. Customers) TO THE USER DO NOT cut off the mains plug from this equip- This equipment has been tested and found to com- ment. If the plug fitted is not suitable for the power ply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pur- points in your home or the cable is too short to suant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are reach a power point, then obtain an appropriate designed to provide reasonable protection against safety approved extension lead or consult your harmful interference when the equipment is operat- dealer.