Chief Constable's Annual Report 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Gd 2020/0058

GD 2020/0058 2020/21 1 Programme for Government October 2020 – July 2021 Introduction The Council of Ministers is pleased to bring its revised Programme for Government to Tynwald. The Programme for Government was agreed in Tynwald in January 2017, stating our strategic objectives for the term of our administration and the outcomes we hoped to achieve through it. As we enter the final year of this parliament, the world finds itself in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic. This and other external factors, such as the prospect of a trade agreement between the UK and the EU, will undoubtedly continue to influence the work of Government in the coming months and years. What the Isle of Man has achieved over the past six months, in the face of COVID-19, has been truly remarkable, especially when compared to our nearest neighbours. The collective response of the people of our Island speaks volumes of the strength of our community and has served to remind us of the qualities that make our Island so special. At the beginning of the pandemic the Council of Ministers suspended the Programme for Government, and any work within it, to bring to bear the complete resources of the public service in the fight against coronavirus as we worked to keep our island and its people safe. Through the pandemic we have seen behaviour changes in society and in Government, and unprecedented times seem to have brought unprecedented ways of working. It is important for the future that we learn from the experiences of COVID and carry forward the positive elements of both what was achieved, and how Government worked together to achieve it. -

COT REPORT 2008 Revised A4 4.11.Indd

HOW TO GET IN TOUCH We hope you will find this document useful. If you would like to make any comment on any aspect of it, please contact: The Clerk of Tynwald Office of the Clerk of Tynwald Finch Road Douglas Isle of Man IM1 3PW telephone: (+44) 1624 685500 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.tynwald.org.im Tynwald Annual Report 2007-08 1 Contents Foreword .......................................................................... 2 Tynwald of today: structure and functions ................... 3 Legislation ........................................................................7 Committee work .............................................................. 9 Tynwald Day 2008 ...........................................................15 Engagement at home and abroad ................................16 Offi ce of the Clerk of Tynwald .......................................18 Appendices 1. List of Members with constituency and parliamentary appointments and parliamentary Committees as at 31st July 2008 ....................................................... 21 2. Offi ce of the Clerk of Tynwald staffi ng as at 31st July 2008 ......................................... 23 3. Expenses of the Legislature Budget 2007/08 and 2008/09 (Pink Book) ................... 24 Published by © the President of Tynwald and the Speaker of the House of Keys, 2008 2 Tynwald Annual Report 2007-08 Foreword Welcome to this, the fi rst Annual service that supports the work Report on the operation of the of Members of Tynwald in their world’s oldest parliament in parliamentary (as opposed to continuous session. governmental) capacity, and also offers a range of services direct to Residents of the Isle of Man, the public. and many who have visited the Island, will be aware of our ancient We are proud of our parliament. parliamentary tradition, which We want to make it easy for people stretches back over 1,000 years in the Isle of Man, and elsewhere, and is still very much part of the to see what it does and to fi nd out Manx way of life. -

Actions Reporting

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT Q1 REPORTING 2017 ACTIONS Actions The Programme for Government ‘Our Island - a special place to live and work’ was approved by Tynwald in January 2017 and in April 2017 a performance framework, ‘Delivering a Programme for Government’, was also approved. The ‘Programme for Government 2016-21’ is a strategic plan that outlines measurable goals for Government. The Council of Ministers have committed to providing a public update against the performance framework on a quarterly basis. This report provides an update on performance through monitoring delivery of the actions committed to. The first quarter for 2017/18 ran April, May, June and reporting for this period has been undertaken during the past 4 weeks. Information has been provided from across Government Departments, Boards and Offices, and the Cabinet Office have collated these to provide this report on Key Performance Indicators. The Programme for Government outlines a number of initial actions that were agreed by the Council of Ministers which will help take Government closer to achieving its overall objectives and outcomes. Departments Boards and Offices have developed action plans to deliver these actions and this report provides an update status report on delivery against these action plans. POLITICAL OUTCOME TITLE Q1 Data Comment SPONSOR Promote and drive the Enterprise Development Fund and Martyn Perkins ensure it is delivering jobs and new businesses for our GREEN We have an economy where Chairman OFT local entrepreneurship is Island supported and thriving -

GRAHAM CREGEEN for Arbory, Castletown & Malewp “Striving to Deliver a Secure Future” Dear Constituent

House of Keys General Election THURSDAY 22nd SEPTEMBER 2016 VOTE FOR GRAHAM CREGEEN For Arbory, Castletown & MalewP “Striving to deliver A secure future” Dear Constituent It has been a great honour to serve the people of Malew and Santon in Tynwald over the last two terms. At this election the boundaries have changed, this now means that Arbory, Castletown and Malew will be combined and I would ask for your support on the 22 September in striving to deliver a secure future for our Island. I am 54 years old, married to Jacqui and have two sons - Andrew is 20, an apprentice joiner, and Ben is 17 and studying for his A levels. I have lived in the south of the Island all my life and was brought up in a family that proudly served the community, with my father, brother and myself having been members of the Port St Mary Lifeboat and Rushen Emergency Ambulance / St. John’s Ambulance. I have also coached over many years at Malew Football Club and the Southern Amateur Swimming Club. Previously, I worked for and then ran the family business and also taught at the Isle of Man College before joining the Post Office. I was elected as Member of the House of Keys for Malew and Santon in 2006 and 2011. The last administration faced a unique set of challenges and many difficult decisions needed to be made; as you will know I was involved in some of these. Some of these were very tough and uncomfortable decisions, but I sought resolutions where common sense prevailed, focusing on the long-term prosperity of the Isle of Man and greater efficiency in government. -

Lonan Parish Commissioners MINUTES

Lonan Parish Commissioners Statutory Meeting Tuesday 23rd February 2016 at 1830 hours at Laxey Commissioners Office. MINUTES Present: Mr J. Faragher, Mr S. Clucas, Mr N. Dobson, Mr S. Clague Mr P. Hill. Apologies: None. Chair: Mr J. Faragher. Clerk: Mr P. Hill. The Meeting commenced at 1835 hours. 103/15 Minutes of the Statutory Meeting of 19th January 2016. Action The Minutes of the Statutory Meeting of 19th January 2016 were examined for accuracy, and it was agreed that they represented a correct statement of events. Proposed by: SC. Seconded by: JF. 104/15 Matters Arising out of the Minutes. a) PH – 98/15(a) – Confirmed that the purchase of the Telephone Kiosk in Pinfold Hill was now complete. b) PH – 99/15(c) – Advised the Board that the Owner of a property under consideration had sadly died. 105/15 Minutes of the Extraordinary Meeting of 11th February 2016. The Minutes of the Extraordinary Meeting of 11th February 2016 were examined for accuracy, and it was agreed that they represented a correct statement of events. Proposed by: SC. Seconded by: ND. 106/15 Matters arising out of the Minutes. a) There were no matters arising. 107/15 Private Sessions 108/15 Planning Applications. a) Planning Application No 16/00099/B of 29.01.16 in respect of erection of extension to dwelling to PH provide additional living accommodation at Hillcot, Croit-e-Quill Road, Lonan, IM4 7JH. Approved. b) Planning Application No 16/00107/B of 02.02.16 in respect of rendering works at Sam’s Barn, Thie PH Eirinagh, Ballaragh Road, Lonan, IM4 7PN. -

Explanatory Memorandum to Tynwald Members

Explanatory Memorandum to Tynwald Members Issued by the Cabinet Office To the Hon. Steve Rodan, President of Tynwald and the Hon. Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled Tynwald – October 2020 1. Title of measure Programme for Government 2020/21, GD 2020/0058 2. Changes in policy In March 2020, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic the Council of Ministers suspended the Programme for Government, and any work within it. Over the past 2 months the Council of Ministers and Departments have reviewed the Actions within the Programme for Government through the refined lens of COVID and the action plan, presented at Appendix A, is now proposed as the Programme for Government 2020/21. 3. Effects of the measure Where actions have been completed and are identified to be withdrawn, they will be removed from the Programme for Government – These are attached as an appendix to this memo and are available online @gov.im. Where the need for new, or follow on actions have been identified, they are proposed for inclusion and have been added to the Programme for Government. Where existing actions require changes to define more clearly what is to be achieved, to reflect changing priorities, to ensure a realistic delivery date is set, or to ensure that political sponsors are assigned, changes to wording, dates or political sponsor are proposed. These changes have been made to the Programme for Government 2020/21. It is to note that the performance year for the Programme for Government 2020/21 will be October 2020 to July 2021. 4. Reasons for the measure When originally approved in 2017, the Programme for Government was described as a ‘living’ document, each year since the Programme for Government has been reviewed and amended to ensure the document and the actions contained therein are current. -

Bilateral Visit from Tynwald, Isle of Man 25 – 27 October 2017 Houses of Parliament, London

[insert map of the region] 1204REPORT/ISLEOFMAN17 Bilateral Visit from Tynwald, Isle of Man 25 – 27 October 2017 Houses of Parliament, London Final Report Contents About the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association UK ........................................................................................ 3 Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Project Overview ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Project Aim & Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Participants & Key Stakeholders ................................................................................................................................... 6 Key Issues .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Results of the Project ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Next Steps ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Acknowledgements -

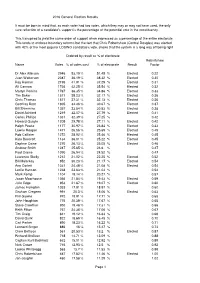

2016 General Election Statistics Summary

2016 General Election Results It must be born in mind that, as each voter had two votes, which they may or may not have used, the only sure reflection of a candidate's support is the percentage of the potential vote in the constituency. This transpired to yield the same order of support when expressed as a percentage of the entire electorate This tends to endorse boundary reforms but the fact that Chris Robertshaw (Central Douglas) was elected with 42% of the most popular LOSING candidate's vote, shows that the system is a long way off being right Ordered by result as % of electorate Robertshaw Name Votes % of votes cast % of electorate Result Factor Dr Alex Allinson 2946 53.19 % 51.45 % Elected 0.22 Juan Watterson 2087 36.19 % 38.32 % Elected 0.30 Ray Harmer 2195 41.91 % 37.29 % Elected 0.31 Alf Cannan 1736 42.25 % 35.54 % Elected 0.32 Martyn Perkins 1767 36.35 % 34.86 % Elected 0.33 Tim Baker 1571 38.23 % 32.17 % Elected 0.36 Chris Thomas 1571 37.31 % 32.13 % Elected 0.36 Geoffrey Boot 1805 34.46 % 30.67 % Elected 0.37 Bill Shimmins 1357 33.54 % 30.53 % Elected 0.38 David Ashford 1219 32.07 % 27.79 % Elected 0.41 Carlos Phillips 1331 32.39 % 27.25 % 0.42 Howard Quayle 1205 29.78 % 27.11 % Elected 0.42 Ralph Peake 1177 30.97 % 26.84 % Elected 0.43 Lawrie Hooper 1471 26.56 % 25.69 % Elected 0.45 Rob Callister 1272 28.92 % 25.46 % Elected 0.45 Kate Beecroft 1134 36.01 % 25.22 % Elected 0.45 Daphne Caine 1270 26.13 % 25.05 % Elected 0.46 Andrew Smith 1247 25.65 % 24.6 % 0.47 Paul Craine 1090 26.94 % 24.52 % 0.47 Laurence Skelly 1212 21.02 -

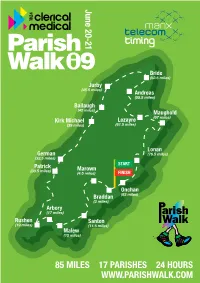

35925 CMI Parish Walk 2009:31470 PW08 Prog

June 20-21 Bride (52.5 miles) Jurby (45.5 miles) Andreas (55.5 miles) Ballaugh (42 miles) Maughold (67 miles) Kirk Michael Lezayre (39 miles) (61.5 miles) Lonan German (76.5 miles) (32.5 miles) Patrick START (30.5 miles) Marown (4.5 miles) FINISH Onchan (83 miles) Braddan (2 miles) Arbory (17 miles) Rushen Santon (19 miles) (11.5 miles) Malew (15 miles) 85 MILES 17 PARISHES 24 HOURS WWW.PARISHWALK.COM A walk through 20 years 2009 celebrates Clerical Medical’s 20th year of sponsorship of the Parish Walk and it has become an established, annual sporting event on the Isle of Man. In many ways this event is unique, involving an 85 mile race-walk around the 17 parishes of the island, within 24 hours. What started as a five year commitment for an outlay of a mere £500 has grown in stature and popularity, attracting walkers from all over the UK and abroad. In 1990 there were only 155 starters but in 2009 there will around 1,700 participants. All at Clerical Medical are delighted with this long and successful association and the company is fully committed to the community of the Isle of Man. PARISH WALK A Welcome from the Race Director Welcome to the 2009 Clerical Medical Parish Walk. The Parish Walk provides a unique challenge to all the entrants and it has captured the imagination of the Manx folk over the years. This year the race has attracted an all-time record entry of 1620. Ahead lies a test of stamina and endurance over 85 miles and 17 Parish Churches all which must be passed before returning to Douglas Promenade within the 24 hour time limit. -

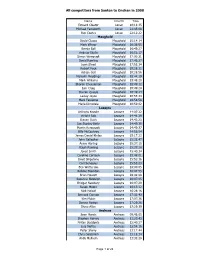

Competitors from Santon to Onchan in 2008

All competitors from Santon to Onchan in 2008 Name Church Time Edward Cleator Lonan 18:11:35 Michael Farnworth Lonan 21:45:08 Ben Coates Lonan 22:12:22 Maughold David Clucas Maughold 15:14:14 Mark Whear Maughold 16:36:55 Bernie Ball Maughold 16:49:27 Andrew Skelly Maughold 16:52:17 Simon Wengradt Maughold 17:00:21 David Rawling Maughold 17:46:27 Leon Steed Maughold 17:51:34 Robert Peck Maughold 18:28:32 Adrian Gell Maughold 18:28:56 Malcolm Meddings Maughold 18:44:19 Mark Williams Maughold 18:48:20 Sharon Cheeseman Maughold 18:49:12 Iain Craig Maughold 18:49:20 Sheron Quayle Maughold 18:49:24 Lesley Joyce Maughold 18:55:34 Mark Fensome Maughold 18:58:58 Maria Dimsdale Maughold 18:59:02 Lezayre Anthony Kneale Lezayre 14:07:22 Wright Rob Lezayre 14:41:29 Steven Quirk Lezayre 14:43:23 Ian Stanley Kelly Lezayre 14:49:35 Martin Kennaugh Lezayre 14:49:37 Billy McCoubrey Lezayre 14:56:54 James Danial Kinley Lezayre 15:17:23 John Gallagher Lezayre 15:31:47 Annie Harling Lezayre 15:37:15 Ralph Pawling Lezayre 15:37:20 Jared Smith Lezayre 15:40:34 Caroline Corteen Lezayre 15:48:01 Lloyd Shipstone Lezayre 15:53:36 Carl Senogles Lezayre 15:55:23 Ben Watterson Lezayre 16:00:05 Robbie Stockton Lezayre 16:01:55 Brian Hewett Lezayre 16:02:08 Suzanne Biddulph Lezayre 16:07:05 Bridget Newbery Lezayre 16:07:20 Susan Moore Lezayre 16:13:12 Nick Halsall Lezayre 16:26:16 Bernard Cannan Lezayre 17:03:40 Kim Makin Lezayre 17:07:36 Denise Foxton Lezayre 17:29:36 Steve Allen Lezayre 17:29:39 Andreas Sean Hands Andreas 09:46:05 Stephen Harvey Andreas 11:20:43 Fintan -

Year 4 Amendments

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT – YEAR 4 Updated 23/09/20 Programme for Government – Year 4 (October 2020 – July 2021) Actions to be removed We have an economy where local entrepreneurship is supported and thriving and more new businesses are choosing to call the Isle of Man home REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE Form local development partnerships and produce local Replaced with 1.11 CABO Ray Harmer* Dec 2019 development plans 1.13 Secure a viable proposal for the redevelopment of the Replaced with 1.12 DOI Marlene Maska* April 2021 Summerland Site 1.13 We have a diverse economy where people choose to work and invest We have Island transport that meets our social and economic needs REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE We have Island transport that meets our social and economic needs REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE *Political Sponsor at the time the action was in progress 2 PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT – YEAR 4 Updated 23/09/20 We have an education system which matches our skills requirements now and in the future REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE 4.01 Introduce a regulatory framework for pre-school services Completed DESC Alex Allinson Dec 2021 4.02 Harmonise our further and higher education to ensure we Completed DESC Alex Allinson June 2018 achieve a more effective and value for money service We have an infrastructure which supports social and economic wellbeing REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE Develop brownfield -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N (HANSARD) S T A N D I N G C O M M I T T E E O F T Y N W A L D O N E C O N O M I C I N I T I A T I V E S B I N G V E A Y N T I N V A A L M Y C H I O N E K E I M Y N D Y C H U R Y F A R R Y S T H I E E R - Y - H O S H I A G H T Douglas, Wednesday, 9th December 2009 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website www.tynwald.org.im Official Papers/Hansards/Please select a year: Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted upon application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. PP115/10 TEI, No. 1 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © Court of Tynwald, 2010 STANDING COMMITTEE, WEDNESDAY, 9th DECEMBER 2009 Members Present: Chairman: The Speaker of the House of Keys (Hon.