Time, Age and Experience in Popular Music Richard Elliott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

A Blank Space Where You Write Your Name: Taylor Swift's Early Late Voice

Richard Elliott, ‘A Blank Space Where You Write Your Name’, conference paper, 2016 A Blank Space Where You Write Your Name: Taylor Swift’s Early Late Voice Richard Elliott [Paper presented at the 2016 EMP Pop Conference, ‘From a Whisper to a Scream: The Voice in Music’, APRIL 14-17 2016, Seattle] Introduction: Late Voice Pop musicians offer a privileged site for the witnessing and analysis of ageing. In my recent work, I use the concept of ‘late voice’ as a way of articulating this and I’ve been exploring issues of time, memory, innocence and experience in modern popular song, with an emphasis on singers and songwriters.1 Lateness, as I’ve used it, refers to five primary issues: chronology (the stage in an artist’s career); the vocal act (the ability to convincingly portray experience); afterlife (the posthumous careers made possible by recorded sound); retrospection (how voices ‘look back’ or anticipate looking back); and the writing of age, experience, lateness and loss into song texts. As part of this work I use the idea of ‘sounded experience’, a term intended to describe how music reflects upon and helps to mediate life experience over extended periods of time (indeed, over lifetimes). Early Late Voice While my initial thoughts about the late voice concept were mainly connected to older singers and the work they produced in the later parts of their careers, I became interested in the possibility of lateness recognised at earlier stages in the life course. In other words, while there’s often a good fit between chronologically late work and Richard Elliott, ‘A Blank Space Where You Write Your Name’, conference paper, 2016 themes of time, age and experience, there’s nothing to exclude such a connection with artists at much earlier stages in their lives. -

Fairport Convention Beyond the Ledge (Filmed Live at Cropredy '98) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Fairport Convention Beyond The Ledge (Filmed Live At Cropredy '98) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Beyond The Ledge (Filmed Live At Cropredy '98) Country: UK Released: 1999 Style: Folk Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1379 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1974 mb WMA version RAR size: 1127 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 845 Other Formats: ASF MP4 WMA DXD MOD APE MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Programme Start : Meet On The Ledge 1 1:50 Arranged By, Performer – Ric SandersWritten-By – Richard Thompson The Lark In The Morning 2 6:14 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Traditional Life's A Long Song 3 3:00 Written-By – Ian Anderson Woodworm Swing 4 3:18 Written-By – Ric Sanders Crazy Man Michael 5 5:03 Written-By – Dave Swarbrick, Richard Thompson Dangerous 6 5:29 Written-By – Kristina Olsen The Flow 7 5:13 Arranged By – Ric SandersWritten-By – Chris Leslie Close To You 8 4:24 Written-By – Chris Leslie The Naked Highwayman 9 4:56 Written-By – Steve Tilston The Hiring Fair 10 6:57 Written-By – Ralph McTell Jewel In The Crown 11 3:31 Written-By – Julie Matthews Cosmic Intermezzo 12 5:29 Written-By – Ric Sanders The Bowman's Retreat 13 3:08 Written-By – Ric Sanders Who Knows Where The Time Goes 14 7:11 Featuring – Chris WhileWritten-By – Sandy Denny Come Haste 15 4:36 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Trad.* Spanish Main 16 4:40 Written-By – Chris Leslie, Maartin Allcock* John Gaudie 17 6:03 Written-By – Chris Leslie Matty Groves 18a 11:14 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Trad.* The Rutland Reel / Sack The Juggler 18b Written-By – Ric Sanders Meet On The Ledge Guest – Anna Ryden*, Chas McDevitt, Chris Knibbs, Chris While, Dave Cousins, David 19 7:10 Hughes , Rabbit*, Maartin Allcock*, P.J. -

1 TWO-CD SET MEET on the LEDGE BRINGS TOGETHER the BEST from INFLUENTIAL FOLK ROCK BAND FAIRPORT CONVENTION Each Year For

1 TWO-CD SET MEET ON THE LEDGE BRINGS TOGETHER THE BEST FROM INFLUENTIAL FOLK ROCK BAND FAIRPORT CONVENTION Each year for the past two decades, one of the most popular folk festivals in Europe has been the annual Fairport Convention reunion. Fusing traditional English folk and American folk and rock ‘n’ roll, Fairport Convention became England’s most influential folk rock band of the late ‘60s-early ‘70s. The starting point for master guitarist and songwriter Richard Thompson, and the zenith for Sandy Denny, whose ethereal voice marked her as one of the U.K.’s most compelling female vocalists, Fairport Convention was one of the most acclaimed bands of its time. Today, Fairport Convention is as much a part of the folk rock tradition as the music itself. The two-CD collection Meet On The Ledge: The Classic Years (1967-1975), released July 27, 1999 on A&M/UMG, is a 32-song, two-and-a-half hour anthology featuring material from the classic albums Fairport Convention (1968), What We Did On Our Holiday (1968), Unhalfbricking (1969), Liege And Lief (1969), Full House (1970), Angel Delight (1971), Babbacombe Lee (1971), Nine (1973) and Rising For The Moon (1975). Along with such classic tracks as “Fotheringay,” the lilting “Book Song,” “I’ll Keep It With Mine,” Thompson’s masterpiece “Meet On The Ledge,” Bob Dylan’s “Percy’s Song,” the beautiful “Who Knows Where The Time Goes,” Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning” and the extended “Sloth,” the collection includes rarities as well as the legendary unreleased recordings of “Bonny Bunch Of Roses” and “Poor Will And The Jolly Hangman.” All of the selections have been digitally remastered from the original tapes. -

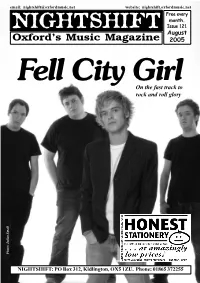

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 121 August Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 Fell City Girl On the fast track to rock and roll glory Photo: Julian Small NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] This month’s issue is dedicated to Albini the Nightshift cat SUPERGRASS play an intimate Ian Parker Band, Michael Myers, show at the Oxford Playhouse this The Invisible and Blue Wax. Music month (Saturday 13th August) as part starts at 7pm. On the Saturday, of a short national tour. The tour is Sunday and Monday, proceedings aimed at promoting new album, kick off at 2pm, with a broad ‘The Road To Rouen’, which marks selection of rock, folk, jazz, blues a change of musical direction for the and acoustic acts, including Leburn, AUGUST band. Kohoutek, Anton Barbeau, Uniting Talking about the tour, singer Gaz the Elements, Sarah Wilson, Laima Every Monday: Coombes said, “It’s gonna be Bite, The Cheesegraters, Tounsi and interesting using these little theatres The Powders. A cheap and extremely THE FAMOUS MONDAY NIGHT BLUES and clubs to show people another cheerful alternative to Reading The best in UK, European and US blues. 8-12. £6 musical side of the band. It’s not Festival. Call 01865 776431 for st something we’ve really done before more details. 1 DIANA BRAITHWAITE (USA) in this way, so we’re excited about it. 8th SHARRIE WILLIAMS & THE WISE We’ll have an old friend playing GOOD AND BAD NEWS for folks GUYS (USA) percussion alongside Danny and his music fans in Oxford this month. -

Fairport Convention Meet on the Ledge the Classic Years (1967-1975) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Fairport Convention Meet On The Ledge The Classic Years (1967-1975) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Meet On The Ledge The Classic Years (1967-1975) Country: Russia Style: Folk Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1464 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1143 mb WMA version RAR size: 1546 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 563 Other Formats: MP3 MMF VQF WAV VOX APE MP1 Tracklist 1-1 Chelsea Morning 3:02 1-2 Fotheringay 3:01 1-3 Mr. Lacey 2:50 1-4 Book Song 3:12 1-5 I'll Keep It With Mine 5:52 1-6 Tale In Hard Time 3:25 1-7 Meet On The Ledge 2:49 1-8 Genesis Hall 3:35 1-9 A Sailor's Life 11:12 1-10 Who Knows Where The Time Goes? 5:07 1-11 Percy's Song 6:47 1-12 Come All Ye 4:58 1-13 Matty Groves 8:06 1-14 Tam Lin 7:09 1-15 Crazy Man Michael 4:36 1-16 Farewell, Farewell 2:36 2-1 Now Be Thankful 2:21 2-2 Bonny Bunch Of Roses 10:45 2-3 Walk Awhile 3:57 2-4 Sloth 9:10 2-5 Poor Will And The Jolly Hangman 5:28 2-6 Journeyman's Grace 4:31 2-7 John Lee 3:01 2-8 Rosie 3:35 2-9 The Plainsman 3:16 2-10 The Hexhamshire Lass 2:27 2-11 Polly On The Shore 4:53 2-12 Bring 'Em Down 5:55 2-13 Rising For The Moon 4:06 2-14 White Dress 3:42 2-15 Stranger To Himself 2:49 2-16 One More Chance 7:50 Credits Compilation Producer – Bill Levenson Design – Wherefore Art? Liner Notes – Patrick Humphries Remastered By – Chris Herles Notes 8-pages booklet Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: AZFC-7741 Matrix / Runout: AZFC-7742 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Meet On The Ledge The 314 564 Fairport -

SLAP Mag Issue 97 (December 2019)

Issue 97 Nov2019 FREE SLAP Supporting Local Arts & Performers WORCESTER’S NEW INDEPENDENT ITALIAN RESTAURANT Traditional Italian food, cooked the Italian way! We create all dishes in our kitchen, using only the finest quality fresh ingredients. f. t. i. SUGO at The Lamb & Flag SUGO at Friar St 30 The Tything 19-21 Friar Street, Worcester Worcester WR1 1JL WR1 2NA 01905 729415 01905 612211 [email protected] [email protected] Hello everyone and welcome to the Winter of discontent, don’t worry, it’ll soon be over, maybe... In these dark days of political turbulence, it’s hard to imagine if we can ever go back to a time when people had respect for each other, whatever their views and opinions. But we can’t let the political elite divide us in this way any longer, society is breaking down and It’s destroying friendships, families and communities. I for one will be glad when it’s all over. But until then let’s concentrate on the things that bring us together - music and the Nov 2019 arts.... As usual, in this issue we look forward to all the wonderful arts events and exhibitions taking place around the three counties. Our front cover is by illustrator Beth Quarmby whose exhibition runs SLAP MAGAZINE throughout November at the Gloucester Guild Hall. It’s comforting to know that the arts communities can break through the divisive Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, political climate and maintain the ability to unite and initiate things Worcester WR1 2RS independently. Telephone: 01905 26660 A perfect example of this is the Worcester Music Festival that [email protected] brings hundreds and acts together in dozens of venues around EDITORIAL the City of Worcester, raising much needed funds for the Foodbank Charity, to help the many people living in crisis in modern Britain, Mark Hogan - Editor see page 38 for the latest news and the highly successful Kate Cox - Arts Editor photography competition. -

D:\Teora\Radu\R\Pdf\Ghid Pop Rock\Prefata.Vp

DedicaÆie: Lui Vlad Månescu PREFAæÅ Lucrarea de faÆå cuprinde câteva sute de biografii çi discografii ale unor artiçti çi trupe care au abordat diverse stiluri çi genuri muzicale, ca pop, rock, blues, soul, jaz çi altele. Cartea este dedicatå celor care doresc så-çi facå o idee despre muzica çi activitatea celor mai cunoscuÆi artiçti, mai noi çi mai vechi, de la începutul secolului çi pânå în zilele noastre. Totodatå am inclus çi un capitol de termeni muzicali la care cititorul poate apela pentru a înÆelege anumite cuvinte sau expresii care nu îi sunt familiare. Fårå a se dori o lucrare foarte complexå, aceastå micå enciclopedie oferå date esenÆiale din biografia celor mai cunoscuÆi artiçti çi trupe, låsând loc lucrårilor specializate pe un anumit gen sau stil muzical så dezvolte çi så aprofundeze ceea ce am încercat så conturez în câteva rânduri. Discografia fiecårui artist sau trupå cuprinde albumele apårute de la începutul activitåÆii çi pânå în prezent, sau, de la caz la caz, pânå la data desfiinÆårii trupei sau abandonårii carierei. Am numit disc de platinå sau aur acele albume care s-au vândut într-un anumit numår de exemplare (diferit de la Æarå la Æarå, vezi capitolul TERMENI MUZICALI) care le-au adus acest statut. Totodatå, am inclus çi o serie de LP-uri BEST OF sau GREATEST HITS apårute la casele de discuri din întreaga lume. De aceea veÆi observa cå discografia unui artist sau a unei trupe cuprinde mai multe albume decât au apårut în timpul vieÆii sau activitåÆii acestora (vezi Jimi Hendrix, de exemplu) çi asta pentru cå industria muzicalå çi magnaÆii acesteia çi-au protejat contractele çi investiÆiile iniÆiale cât mai mult posibil, profitând la maximum de numele artiçtilor çi trupelor lor. -

Susana Seivane Con Il Padre Álvaro

Distribuzione gratuita esclusivamente in formato digitale senza pubblicità Anno 6 - n°55 - 2017 - € 0,00 www.lineatrad.com - italia: www.lineatrad.it - internazionale: www.lineatrad.eu Susana Seivane con il padre Álvaro al festival La Zampogna, Maranola La Baìo di Sampeyre Celtic Connections 2017 FIMU 2017 a Belfort Samurai Championnat de Bretagne, Motion Trio de musique et de danse traditionnelles Novità discografiche n. 55 - 2017 Contatti: [email protected] - www.lineatrad.com - www.lineatrad.itSommario - www.lineatrad.eu Soapkills, Lula Pena, Festival La zampogna Il FIMU a Belfort Gigi Biolcati, —04 a Maranola —26 —33 04 26 33 Frank Cusumano Acid Arab, Flame Parade, La Baìo di Sampeyre Dalla Polonia: Djamnolulù swing band, —10 e dei paesi limitrofi —28 Motion Trio —34 10 28 34 Gabriella Lucia Grasso —18 Championnat de Bretagne —30 I Samurai —35 Loreena McKennitt, 18 de musique et danse trad 30 della fisarmonica 35 Tizio Bononcini Zampogneria, Micrologus, I 50 anni dei Fairport Paolo Gerbella, —24 al Celtic Connections —32 24 32 Erodoto project Eventi Cronaca Interviste Recensioni Argomenti Womex 2017 di Loris Böhm Editoriale iamo arrivati a Pasqua, archi- tutte che se si vuol far sopravvivere facebook un mezzo imprescindibile viamo dunque zampogne e cia- una fonte di informazione autorevole, per divulgare e leggere notizie, addirit- Sramelle e riprendiamo a seguire i bisogna impegnarsi in qualche modo tura indispensabile per ampliare il pro- concerti “random”, parliamo di novità in prima persona. prio giro di conoscenze e affari. discografiche (non sono molte in ve- Capisco che sono tempi brutti, che la Se la quantità fine a se stessa va a di- rità quelle che ci arrivano in sede), e crisi ha svuotato la fiducia degli italiani, scapito della qualità (e attendibilità), si- diamo uno sguardo a come si annun- che la recessione ha svuotato i conti gnifica che è sbagliato tutto il sistema, cia questo 2017 appena iniziato. -

Fairport Convention Richard Looming Behind Her, I Thought "Hobbit and June 68 Goblin!"

WHO KNOWS WHERE THE TIME WENT ? MIKE WEBER 'S GUIDE TO THE ESSENTIAL 1967 - 1979 Fairport Convention Richard looming behind her, i thought "Hobbit and June 68 goblin!" Time Will Show the Wiser Jack o Diamonds Unhalfbricking Chelsea Morning July 69 (US November 69, with the The first album, when they stupidest cover ever... were seen as sort of a British [below]) Jefferson Airplane; Judy Dy- ble on vocals, Martin Lamble Virtually this entire album is on drums, Ashley (Tyger) Important: Hutchings bass, Richard Thompson & Simon Nicol Genesis Hall various guitars and mandolin, Si Tu Dois Partir Ian MacDonald (later Ian Mat- Who Knows Where the thews) vocals. Time Goes Percy's Song "Fairport" was the house Simon's family lived in in Million Dollar Bash Muswell Hill; they got together in a spare room to practise, henc, "The Fairport Convention", though the Personnel as before "The" disappeared pretty quickly. There are two Joni (Matthews on only one track); Mitchell songs on this album -- which came out before Dave Swarbrick on session fiddle Joni's own version did, i believe. Mitchell's manager or producer (i forget with), Warwick Boyd, sent the Genesis Hall was a well-known and large London songs to their producer, his brother,Joe Boyd, an expa- squat that was eventually raided by the police. Rich- triate American living in London. ard's father was a policeman; "Genesis Hall" the song is about neutrality and ambivalence in emotional cir- cumstance. ("My father he rides with your sheriffs/ What We Did on Our and I know he would never mean harm/But to see both sides of a quarrel they say/Is to judge without fear or Holidays alarm...") January 69 You may know Judy Collins' version of "Where the (The July 69 US release was Time Goes" -- it was, i understand, the second eral entitled simply "Fairport Con- song Sandy wrote, written when she was 19. -

Rapid River Magazine June 2008

RAPID RIVER ARTS ART TALK Asheville Area Arts Council’s Purple Ball BY MELISSA SMITH rom lavender to deep plum, the decadence, indulgence, and debauchery. purple spectrum is the color of Finally, guests will converge for the finale choice at this year’s Asheville Area party, Ultra Violet, where guests experi- Arts Council’s fundraiser ball com- ence a futuristic, Matrix-like, cyberspace. ing up on Saturday, June 14. Four theme parties through- If you go Fout downtown Asheville and an anticipated crowd of nearly 1,000 will be cloaked in the royal color, which if Asheville Area Arts Council’s Purple Ball, Saturday, June 14, from 6 p.m. to 1 a.m. you aren’t familiar with the ball, its color changes each year. Now in its seventh Where: Four locations throughout year, the Purple Ball raises funds for the downtown Asheville (Scandals, Nashwa Asheville Area Arts Council’s educational Nightclub, Haywood Park Hotel Atrium, programs and artist grants. This year’s ball & Haywood Park Hotel). A trolley service is sponsored in part by Charlotte Street and LaZoom Tours, will feature live entertainment while in transit, providing Computers. free shuttle service between the parties. The Purple Ball is an evening of four hosted theme parties featuring delectable Ticket Prices & Info: Patron tickets are eats, specialty cocktails, and top-notch $150, $175 after June 1, and $200 at the local entertainment. The evening kicks off door and grant access to all four parties. for Patron ticket holders at Violet Femme, A ticket to either IndiGo! or Purple Reign, followed by two parties running concur- plus the finale, Ultra Violet, costs $75, rently. -

Review: "Fairport Convention: 35Th Anniversary Concert (DVD)"

Review: "Fairport Convention: 35th Anniversary Concert (DVD)" - Sea ... http://www.seaoftranquility.org/reviews.php?op=showcontent&id=5223 Search in Topics All Topics Go! June 4, 2007 6 Main Menu · Home · Topics · Sections · REVIEWS · Web Links Fairport Convention: 35th Anniversary Concert (DVD) · Recommend Us · Submit News Recorded at the lovely Anvil Theatre in Basingstoke, England in 2002, Fairport Convention’s 35th Anniversary Concert amply conveys the charm · Top 10 Lists and warmth of a Fairport gig. For two hours, the brown ale flows, good · FAQ humor warms the heart and folk songs that are hundreds of years old fill the air once again. For those who may not know, albums such as · Contact Us Unhalfbricking, Liege and Lief and Full House are all masterpieces that · Stats must be investigated immediately. Forget trying to unravel the family tree that is Fairport Convention; lineup changes have Visit Our Friends At: become as second nature as the next pub visit for these venerable folk rockers. Suffice to say that guitarist/vocalist Simon Nicol is the only member from the original lineup that once included the formidable team of Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny. But bassist Dave Pegg has been with the band since 1970 and has become every bit the leader and spokesperson for Fairport as Simon Nicol. Rounding out the current lineup is drummer Gerry Conway, multi Who's Online instrumentalist Chris Leslie and violinist Ric Sanders. More than a mere “greatest hits” set list, the 35th Anniversary Concert contains several new There are currently 37 songs from Fairport’s then current IIIV studio album as well as a few relatively obscure gems guests online.