1531 CSPV 4.694 Cromwell.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Duchess Park

Duchess Park Bee Orchid on Duchess Park History and Natural History Volume 1 - An Introduction (A work in progress at August 2015) David Cudby Duchess Park History and Natural History – Volume 1 This book is dedicated to all residents and visitors to Duchess Park, present and future, who have an interest in local history, or who are, or might be persuaded to become interested in understanding, loving and conserving the site and its flora and fauna. The views are my own. Why does including local history in this book matter? It matters for two major reasons. First because many people derive a great deal of pleasure from reading about past events and enjoy the perspective that it gives in understanding local custom and practice, previous land ownership and land use. Secondly, for many of us, myself included, knowing something about where our little patch of land fits into previous land ownership and who lived here and used that land gives a sense of place and helps in feeling grounded or at home where we live. It is only by having this sense of place that we can feel the emotion that will motivate us to protect and conserve what we have inherited. Why does conservation matter? Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realize that we can't eat money Treat the Earth well: It was not given to you by your parents it was loaned to you by your children (Native American Proverbs) August 2015 Page 2 Duchess Park History and Natural History – Volume 1 Contents of Volume 1 Page -

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH and TIME

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH AND TIME BY HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN, P.C., G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O., G.C.I.E. 1954 Simon and Schuster, New York Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. First Printing Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 54-8644 Dewey Decimal Classification Number: 92 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY H. WOLFF BOOK MFG. CO., NEW YORK, N. Y. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. CONTENTS PREFACE BY W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM Part One: CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH I A Bridge Across the Years 3 II Islam, the Religion of My Ancestors 8 III Boyhood in India 32 IV I Visit the Western World 55 Part Two: YOUNG MANHOOD V Monarchs, Diplomats and Politicians 85 VI The Edwardian Era Begins 98 VIII Czarist Russia 148 VIII The First World War161 Part Three: THE MIDDLE YEARS IX The End of the Ottoman Empire 179 X A Respite from Public Life 204 XI Foreshadowings of Self-Government in India 218 XII Policies and Personalities at the League of Nations 248 Part Four: A NEW ERA XIII The Second World War 289 XIV Post-war Years with Friends and Family 327 XV People I Have Known 336 XVI Toward the Future 347 INDEX 357 Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. -

Janet Gurkin Altman Approaches to a Form

Janet Gurkin Altman Approaches to a Form EPISTOLARITY Approaches to a Form By Janet Gurkin Altman Though the letter's potential as an artistic form and a narrative vehicle has been recog nized by writers of nearly every nationality and period from Ovid, in the Epistulae Heroidum, to Saul Bellow, in Herzog, episto lary literature has only recently become the object of close and sustained critical scrutiny as a result of the revival of the letter form in contemporary fiction, and a growing recogni tion that the genre was not, in fact, abandoned following the period of its greatest popularity in the eighteenth century. This was the age that produced such classics as Montesquieu's Lettres persanes, Richardson's Pamela and Clarissa, Rousseau's La Nouvelle Héloïse, Smollett's Humphry Clinker, Goethe's Werth er, and Laclos's Les Liaisons dangereuses. Such well-known works, Professor Altman suggests, though they represent a wide di versity in style, plot, and characterization, re veal a surprising number of similar literary structures or intriguingly persistent patterns when read together with other examples of the epistolary genre. And these structures — re curring thematic relations, character types, narrative events and organization — can, in turn, be related to properties inherent in the letter itself. For in numerous instances, these basic formal and functional characteristics of the letter, far from being purely ornamental, significantly affect the way in which meaning is constructed, consciously and unconscious ly, by both writers and readers. The epistolary novel. Dr. Altman points out, was born in an age when novelists like Diderot and Sterne had moved beyond story telling to indulge in playful reflection upon history and fiction, and the means by which historical and fictional events are recounted. -

Emp, An& Juapoleon

gmertca, , ?|emp, an& JUapoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. Ohio Sttite University Press $6.50 America, IXuaata, S>emp, anb Napoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. On the twelfth of June, 1783, a ship of 500 tons sailed into the Russian harbor of Riga and dropped anchor. As the tide pivoted her around her mooring, the Russians on the waterfront could see clearly the banner that she flew — a strange device of white stars on a blue ground and horizontal red and white stripes. Russo-American trade had irrevocably begun. Merchants — Muscovite and Yankee — had met and politely sounded the depths of each other's purses. And they had agreed to do business. In the years that followed, until 1812, the young American nation became economically tied to Russia to a degree that has not, perhaps, been realized to date. The United States desperately needed Russian hemp and linen; the American sailor of the early nineteenth century — who was possibly the most important individual in the American economy — thought twice before he took any craft not equipped with Russian rigging, cables, and sails beyond the harbor mouth. To an appreciable extent, the Amer ican economy survived and prospered because it had access to the unending labor and rough skill of the Russian peasant. The United States found, when it emerged as a free (Continued on back flap) America, Hossia, fiemp, and Bapolcon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 America, llussia, iicmp, and Bapolton American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1811 BY ALFRED W. -

The Heraldry of the Johnstons

S«Wv%%* (S -Jlarvty -Jofy J#ion *) o s This volume, formerly in the Library of William Rae Macdonald, Esq., Albany Herald, was bequeathed to the Advocates' Library by his widow, Mrs W. R. Macdonald, who died on 21st October 1924. National Library of Scotland *B0001 94038* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofjohnst1905john THE Heraldry of tbe Johnstons NOTE. 120 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only ioo will be offered to the Public. THE Heraldry of the Johnstons WITH NOTES ON THE DIFFERENT FAMILIES, THEIR ARMS AND PEDIGREES BY G. HARVEY JOHNSTON AUTHOR OF "SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCM V 9 ! — Preface. THE JOHNSTONS are often referred to as the "gentle" Johnstons, and in Border ballad, entitled "The Lads of Wamphray," we find the Galliard, the " after stealing Sim Crichton's winsom dun," calling an invitation : " Now Simmy, Simmy of the side, Come out and see a Johnston ride Here's the bonniest horse in a' Nithside, And a gentle Johnston aboon his hide." From this we may gather that the term " gentle " is derived from a long pedigree, and not from the ancient manners of the race. Their past history makes lively reading ; the common foe across the Border was always an outlet for superfluous energy ; the long and tragic feud with the Maxwells kept them busy ; and when these excitements failed them, they had little wars amongst themselves to prevent their swords rusting in the scabbards. -

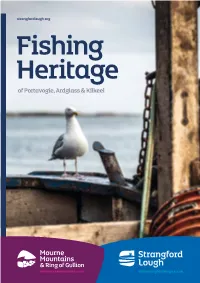

Fishing Heritage of Portavogie Guide (PDF)

strangfordlough.org Fishing Heritage of Portavogie, Ardglass & Kilkeel 3 Copeland Islands A2 Belfast K y l e Lough s to n e R d A2 d W R h d i y n A48 R n e e n y y e o W h H g m i n au y d ll i l U i l l K l p m a p i B e l r l G R r a d n s h a Ho R lyw d Contents A21 Pushing the boat out o o d R d d R y e d b R b n A20 A r u b o A22 d W R 5 The local catch Fishing has been a major industry in County K n i r l A20 b u r b d i R g g h n e i s t n n 6 Improved fishing gear R a Down for many years. Three ports - Kilkeel, n t Steward R d d u M C A55 M d a R C rd r y b e Rd Dun 7 Changing fisheries om ove Portavogie and Ardglass - remain at the C r Rd m centre of the fishing industry today. Their 8 Navigating change Stu p Rd B a ll A2 ydrai Chapel n R communities revolve around the sea. Local 9 Weather & hidden danger d Island A23 d R T rry u 10 People’s stories: past & present a l Lisburn l people and their traditions have strong ties Carrydu u y Q n A2 a k i l 6 l A3 R Rd 13 Fishing moves forward d e to the water. -

Catalogue 60

CATALOGUE 60 DIAMOND JUBILEE CATALOGUE A SPECIAL COLLECTION OF ROYAL AUTOGRAPHS AND MANUSCRIPTS FROM ELIZABETH I TO ELIZABETH II To Commemorate the Celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II I have put together a collection of Royal documents and photographs spanning the 400 years from the first Elizabethan age of ‘Gloriana’ to our own Elizabethan era. It includes every King and Queen in between and many of their children and grandchildren. All purchases will be sent by First Class Mail. All material is mailed abroad by Air. Insurance and Registration will be charged extra. VAT is charged at the Standard rate on Autograph Letters sold in the EEC, except in the case of manuscripts bound in the form of books. My VAT REG. No. is 341 0770 87. The 1993 VAT Regulations affect customers within the European Community. PAYMENT MAY BE MADE BY VISA, BARCLAYCARD, ACCESS, MASTERCARD OR AMEX from all Countries. Please quote card number, expiry date and security code together with your name and address and please confirm answerphone orders by fax or email. There is a secure ordering facility on my website. All material is guaranteed genuine and in good condition unless otherwise stated. Any item may be returned within three days of receipt. COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: Thomas Harrison Anthony & Austin James Farahar http://antiquesphotography.wordpress.com E-mail: [email protected] 66a Coombe Road, Kingston, KT2 7AE Tel: 07843 348748 PLEASE NOTE THAT ILLUSTRATIONS ARE NOT ACTUAL SIZE SOPHIE DUPRÉ Horsebrook House, XV The Green, Calne, -

SSJ 23 1 Oct/XL:Layout 1

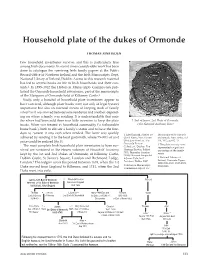

Household plate of the dukes of Ormonde THOMAS SINSTEDEN Few household inventories survive, and this is particularly true among Irish documents. In recent times considerable work has been done to catalogue the surviving Irish family papers at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland and the Irish Manuscripts Dept, National Library of Ireland, Dublin. Access to this research material has led to several books on life in Irish households and their con- tents.1 In 1895–1912 the Historical Manuscripts Commission pub- lished the Ormonde household inventories, part of the manuscripts of the Marquess of Ormonde held at Kilkenny Castle.2 Sadly, only a handful of household plate inventories appear to have survived, although plate books were not only of legal (estate) importance but also an essential means of keeping track of family silver3 as it was moved between one residence and another, depend- ing on where a family was residing. It is understandable that once the silver had been sold there was little incentive to keep the plate 1 Seal of James, 2nd Duke of Ormonde. books. Silver was treated as household commodity (‘a fashionable (The National Archives, Kew) home bank’), both to elevate a family’s status and to have the free- dom to convert it into cash when needed. The latter was quickly 1 Toby Barnard, Making the Manuscripts of the Marquis achieved by sending it to the local goldsmith, where 75–80% of cost Grand Figure, New Haven of Ormonde, New series, vol price could be realised [fig 5]. 2004; Jane Fenelon, ‘The VII, 1912, pp512–13. -

Ormond Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No.176 Ormonde Papers (Additional) (SEE ALSO COLLECTION LIST No.17) (MSS 48,367-377) A collection of estate property deeds generated by the Butler family relating to properties in Counties Kilkenny, Tipperary and Carlow, as well as some properties in northern England (1635-c.1940) Compiled by Owen McGee, 2011 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 2 I. Estate Papers.................................................................................................................. 5 I.i. Kilkenny ...................................................................................................................5 I.i.1. Kilkenny City (1699-1880) ................................................................................ 5 I.i.2. Kilkenny County (1668-1780) ......................................................................... 10 I.i.3. Garryricken Estate, Co. Kilkenny (including town of Callan), 1675-1856 ..... 16 I.i.4. Dunmore Estate, Co. Kilkenny (1668-1902).................................................... 22 I.ii. Tipperary .............................................................................................................. 27 I.ii.1. County Tipperary (including town of Carrick-on-Suir), 1612-1901............... 27 I.ii.2. Lease agreements for the Kilcash Estate (1709-1891).................................... 45 1.iii. County Carlow Estate (1669-1780) .................................................................. -

Montrose and Modern Memory: the Literary After-Life of the First Marquis of Montrose

Montrose and Modern Memory: the literary after-life of the first marquis of Montrose Catriona M. M. MacDonald Scottish Literary Review, Volume 6, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2014, pp. 1-27 (Article) Published by Association for Scottish Literary Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/548089 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 11:30 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] CATRIONA M. M. MACDONALD1 Montrose and Modern Memory: the literary after-life of the ¢rst marquis of Montrose Abstract By addressing the ways in which historical and ¢ctional texts from the mid-seventeenth century to the present have depicted the ¢rst marquis of Montrose (1612^1650), this article emphasises the in£u- ence of religious partisanship on Scottish historiography; the distort- ing lens that Romanticism o¡ered to those seeking to understand the religious and national trauma of the covenanting wars; the in£u- ence of pre-1745 events on the interests of Victorian literary Jacobit- ism; the impact of populism on the cult of Montrose; and the revisionism of twentieth and twenty-¢rst century texts that question the dichotomy of cavalier and covenant presented by earlier writers and suggest a subversive reading of the heroism evoked in conven- tional appreciations of the life of the marquis. Instead of the monuments in stone, the festivals, and the commercialisation that commemorated and exploited the contributions of William Wallace, Robert Burns and others to the grand narratives of Scotland’s history, it was the written word -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia)