RICHARD STRAUSS Three Hymns / Opera Arias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gustav Mahler : Conducting Multiculturalism

GUSTAV MAHLER : CONDUCTING MULTICULTURALISM Victoria Hallinan 1 Musicologists and historians have generally paid much more attention to Gustav Mahler’s famous career as a composer than to his work as a conductor. His choices in concert repertoire and style, however, reveal much about his personal experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his interactions with cont- emporary cultural and political upheavals. This project examines Mahler’s conducting career in the multicultural climate of late nineteenth-century Vienna and New York. It investigates the degree to which these contexts influenced the conductor’s repertoire and questions whether Mahler can be viewed as an early proponent of multiculturalism. There is a wealth of scholarship on Gustav Mahler’s diverse compositional activity, but his conducting repertoire and the multicultural contexts that influenced it, has not received the same critical attention. 2 In this paper, I examine Mahler’s connection to the crumbling, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century depiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as united and question whether he can be regarded as an exemplar of early multiculturalism. I trace Mahler’s career through Budapest, Vienna and New York, explore the degree to which his repertoire choices reflected the established opera canon of his time, or reflected contemporary cultural and political trends, and address uncertainties about Mahler’s relationship to the various multicultural contexts in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, I argue that Mahler’s varied experiences cannot be separated from his decisions regarding what kinds of music he believed his audiences would want to hear, as well as what kinds of music he felt were relevant or important to share. -

Download Booklet

570895bk RStrauss US:557541bk Kelemen 3+3 3/8/09 8:42 PM Page 1 Antoni Wit Staatskapelle Weimar Antoni Wit, one of the most highly regarded Polish conductors, studied conducting with Founded in 1491, the Staatskapelle Weimar is one of the oldest orchestras in the world, its reputation inextricably linked Richard Henryk Czyz˙ and composition with Krzysztof Penderecki at the Academy of Music in to some of the greatest works and musicians of all time. Franz Liszt, court music director in the mid-nineteenth Kraków, subsequently continuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He also century, helped the orchestra gain international recognition with premières that included Wagner’s Lohengrin in graduated in law at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Immediately after completing 1850. As Weimar’s second music director, Richard Strauss conducted first performances of Guntram and STRAUSS his studies he was engaged as an assistant at the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra by Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel. The orchestra was also the first to perform Strauss’s Don Juan, Macbeth and Death Witold Rowicki and was later appointed conductor of the Poznan´ Philharmonic. He and Transfiguration. After World War II Hermann Abendroth did much to restore the orchestra’s former status and Symphonia domestica collaborated with the Warsaw Grand Theatre, and from 1974 to 1977 was artistic director quality, ultimately establishing it as one of Germany’s leading orchestras. The Staatskapelle Weimar cultivates its of the Pomeranian Philharmonic, before his appointment as director of the Polish Radio historic tradition today, while exploring innovative techniques and wider repertoire, as reflected in its many recordings. -

Richard Strauss - Éléments De Style Jacques Amblard

Richard Strauss - Éléments de style Jacques Amblard To cite this version: Jacques Amblard. Richard Strauss - Éléments de style. 2019. hal-02314490 HAL Id: hal-02314490 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02314490 Preprint submitted on 12 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Richard Strauss Éléments de style Jacques Amblard, LESA (EA-3274) Abstract : le compositeur Richard Strauss, souvent taxé de « postromantique » et échappant ainsi à l’histoire, n’en fut pas moins, probablement, le plus important musicien allemand du premier XXe siècle. L’examen détaillé de son parcours nous permet de déceler un romantisme en réalité modernisé, dès la fin du XIXe siècle. La densité n’est plus celle de Wagner mais double chez ce « Richard II ». On pourrait parler de « poly-romantisme ». Ce dernier style se mélange ensuite, d’une façon originale, à partir du Chevalier à la rose, avec un néoclassicisme mozartien. Comment l’équilibre entre une telle densité lyrique et la légèreté mozartienne est-il possible ? Ce miracle dialectique culmine pourtant dans Capriccio. Ce texte fut rédigé en 2014, publié en 2016 dans Brahms (encyclopédie en ligne de l’IRCAM). -

Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Octavian and the Composer: Principal Male Roles in Opera Composed for the Female Voice by Richard Strauss Melissa Lynn Garvey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC OCTAVIAN AND THE COMPOSER: PRINCIPAL MALE ROLES IN OPERA COMPOSED FOR THE FEMALE VOICE BY RICHARD STRAUSS By MELISSA LYNN GARVEY A Treatise submitted to the Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Melissa Lynn Garvey defended on April 5, 2010. __________________________________ Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative __________________________________ Matthew Lata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I’d like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, grandparents, aunt, and siblings, whose unconditional love and support has made me the person I am today. Through every attended recital and performance, and affording me every conceivable opportunity, they have encouraged and motivated me to achieve great things. It is because of them that I have reached this level of educational achievement. Thank you. I am honored to thank my phenomenal husband for always believing in me. You gave me the strength and courage to believe in myself. You are everything I could ever ask for and more. Thank you for helping to make this a reality. -

Temporada D'òpera 1984 -1985

GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU TEMPORADA D'ÒPERA 1984 -1985 SALOME EAU SAUVAGE EXTRÊME Christian Dior EAU DE TCHLETTE CONCBiTRÉE C-Kristian Dior PAPIS inventa Eau Sauvage Extrême Eau Sauvage Extrême: aún más intenso aún más presente aún más Eau Sauvage. GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Temporada d'òpera 1984/85 CONSORCI OKI. GRAN TEATRE DEE LICEU (;knerali·|'\t de cataeenva aji ntament de a\rceu)na s(k:ietat del cran teatre del i.icel SAAB 900 Turbo 168: 2000 cm.'; 4 válvulas por cilindro; doble árbol de levos; intercooler y sistemo A.P.C.; 175 C.V.:5velocidodes; 210l<m/h; oceleroción de 0-100 km: 8,75sg; consumo 90km/h:7,l 1,120km/h:9,5l;troccióndelontera. A más de 200 km. por hora, el mundo combla. Por eso es indispensa¬ ble poder confiar en el vehículo que los alcance. Plenamente, como se puede confiar en un SAAB. Poraue el SAAB es un coche concebido en uno de los centros más avanzados del mundo en tecnología aeronáu¬ tico: SAAB SCANIA. Incorporando los últimos avances de su potencia tecnolágico, SAAB presenta el nuevo SAAB 900 Turbo-16, equipado con el revolucionario motor turbo de 16 vál¬ vulas e intercooler, que desarrolla 175 CV. Lo tecnología elevado o la máximo potencia, que Vd. puede comprobar en su concesionario SAAB. Personalidad en coche koÜnUc Tenor Viñas, 8 - BARCELONA- Tel: 200 73 08 m SALOMÉ Drama musical en 1 acte segons el poema homònim d'Oscar WÜde Música de Richard Strauss Dijous, 7 de febrer de 1985, a les 21 h., funció num. -

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été - A survey of the discography by Ralph Moore The song cycle Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 consists of settings by Hector Berlioz of six poems written by his friend Théophile Gautier. Strictly speaking, they do not really constitute a cycle, insofar as they are not linked by any narrative but only loosely connected by their disparate treatment of the themes of love and loss. There is, however, a neat symmetry in their arrangement: two cheerful, optimistic songs looking forward to the future, frame four sombre, introspective songs. Completed in 1841, they were originally for a mezzo-soprano or tenor soloist with a piano accompaniment but having orchestrated "Absence" in 1843 for his lover and future wife, Maria Recio, Berlioz then did the same for the other five in 1856, transposing the second and third songs to lower keys. When this version was published, Berlioz specified different voices for the various songs: mezzo-soprano or tenor for "Villanelle", contralto for "Le spectre de la rose", baritone (or, optionally, contralto or mezzo) for "Sur les lagunes", mezzo or tenor for "Absence", tenor for "Au cimetière", and mezzo or tenor for "L'île inconnue". However, after a long period of neglect, in their resurgence in modern times they have generally become the province of a single singer, usually a mezzo-soprano – although both mezzos and sopranos sometimes tinker with the keys to ensure that the tessitura of individual songs sits in the sweet spot of their voices, and transpositions of every song are now available so that it can be sung in any one of three - or, in the case of “Au cimetière”, four - key options; thus, there is no consistency of keys across the board. -

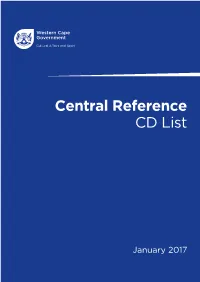

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

Ariadne Auf Naxos Soile Isokoski ∙ Sophie Koch Jochen Schmeckenbecher ∙ Johan Botha

RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNE AUF NaXOS SOILE ISOKOSKI ∙ SOPHIE KoCH JOCHEN SCHMECKENBECHER ∙ JOHAN BOTHA ORCHESTER DER WIENER STAATSOPER conducted by CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN staged by SVEN-ERIC BECHTOLF WIENER STAATSOPER RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNE AUF NaXOS Orchestra Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper Here is one of the truly overwhelming successes in recent opera Conductor Christian Thielemann history: Christian Thielemann’s sensational return to the Vienna State Stage Director Sven-Eric Bechtolf Opera to conduct his first-ever performances there of Richard Strauss, with an ideal cast in an acclaimed production of Ariadne auf Naxos. “A triumph [...] world stars and ensemble shine” (Die Presse). “Strauss Primadonna (Ariadne) Soile Isokoski in all his glory”(Wiener Zeitung). “Festival standard [...] electrifying The Composer Sophie Koch excitement” (Kronen Zeitung). A Music Teacher Jochen Schmeckenbecher The Tenor (Bacchus) Johan Botha Director Sven-Erich Bechtolf “has again delved deeply into music Zerbinetta Daniela Fally and text”, observed the opera magazine Opernnetz in its rave review Harlequin Adam Plachetka of the performance captured here. “In Rolf Glittenberg’s beautiful Scaramuccio Carlos Osuna Jugendstil salon, he is constantly in touch with the heartbeat of the Truffaldin Jongmin Park story [...] For Bechtolf it is the subtle development of the characters Brighella Benjamin Bruns and their relationships with each other, as well as the work’s delicate The Dancing Master Norbert Ernst irony, that remain of paramount importance. As Ariadne, Soile Isokoski radiates enchanting vocal beauty as she forms endless nuances in one The Major-Domo Peter Matić blossoming phrase after another. Daniela Fally sings the gruellingly Lackey Marcus Pelz difficult part of Zerbinetta with great flexibility, acting it with nonchalant A Wigmaker Won Cheol Song coquettishness. -

Hailed As One of the Leading Exponents of the Bel Canto and Lyric

JOHN KANEKLIDES, TENOR Hailed by Opera News as “the very picture of youthful optimism and potential,” John Kaneklides is quickly establishing himself as a celebrated tenor of his time. After being named a finalist in the Nico Castel International Master Singer Competition in 2011, Kaneklides was personally championed by the prolific diction coach and opera translator - a mentorship that propelled his career in opera, art song, and oratorio. This season Kaneklides will create the role of the Guide who mysteriously transforms into Narciso Borgia in the world premiere of Harold Blumenfeld’s Borgia Infami with Winter Opera Saint Louis. He will also reprise the title role in Les contes d’Hoffmann with Skylight Music Theatre and make his role debut as Ralph Rackstraw in H.M.S. Pinafore with the Young Victorian Theatre Company. Additionally, Kaneklides will return to St. Petersburg Opera as Alfredo in La traviata. On the concert stage he can be heard as the tenor soloist in Orff’s Carmina Burana with the Florida Orchestra, under the baton of Michael Francis. Kaneklides will also be concertizing with Lyric Opera Baltimore, Gulfshore Opera and throughout North Carolina. The 2016-2017 season brought Kaneklides rave reviews for his role debut in the title role of Les contes d’Hoffmann. The Tampa Bay Times said he, “makes for a mesmerizing lead as the poet Hoffmann, equipped with matinee idol looks and a electric sound that continues to surprise.” Kaneklides also starred as Villiers, The Duke of Buckingham in the highly anticipated New York premier of Carlisle Floyd’s most recent opera, The Prince of Players, with the Little Opera Theatre of New York. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO

**MANY OF THESE SINGERS SPANNED MORE THAN ONE VOICE TYPE IN THEIR CAREERS!** COLORATURA and LYRIC COLORATURA SOPRANO: DRAMATIC SOPRANO: Joan Sutherland Maria Callas Birgit Nilsson Anna Moffo Kirstin Flagstad Lisette Oropesa Ghena Dimitrova Sumi Jo Hildegard Behrens Edita Gruberova Eva Marton Lucia Popp Lotte Lehmann Patrizia Ciofi Maria Nemeth Ruth Ann Swenson Rose Pauly Beverly Sills Helen Traubel Diana Damrau Jessye Norman LYRIC MEZZO: SOUBRETTE & LYRIC SOPRANO: Janet Baker Mirella Freni Cecilia Bartoli Renee Fleming Teresa Berganza Kiri te Kanawa Kathleen Ferrier Hei-Kyung Hong Elena Garanca Ileana Cotrubas Susan Graham Victoria de los Angeles Marilyn Horne Barbara Frittoli Risë Stevens Lisa della Casa Frederica Von Stade Teresa Stratas Tatiana Troyanos Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Carolyn Watkinson DRAMATIC MEZZO: SPINTO SOPRANO: Agnes Baltsa Anja Harteros Grace Bumbry Montserrat Caballe Christa Ludwig Maria Jeritza Giulietta Simionato Gabriela Tucci Shirley Verrett Renata Tebaldi Brigitte Fassbaender Violeta Urmana Rita Gorr Meta Seinemeyer Fiorenza Cossotto Leontyne Price Stephanie Blythe Zinka Milanov Ebe Stignani Rosa Ponselle Waltraud Meier Carol Neblett ** MANY SINGERS SPAN MORE THAN ONE CATEGORY IN THE COURSE OF A CAREER ** ROSSINI, MOZART TENOR: BARITONE: Fritz Wunderlich Piero Cappuccilli Luigi Alva Lawrence Tibbett Alfredo Kraus Ettore Bastianini Ferruccio Tagliavani Horst Günther Richard Croft Giuseppe Taddei Juan Diego Florez Tito Gobbi Lawrence Brownlee Simon Keenlyside Cesare Valletti Sesto Bruscantini Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau