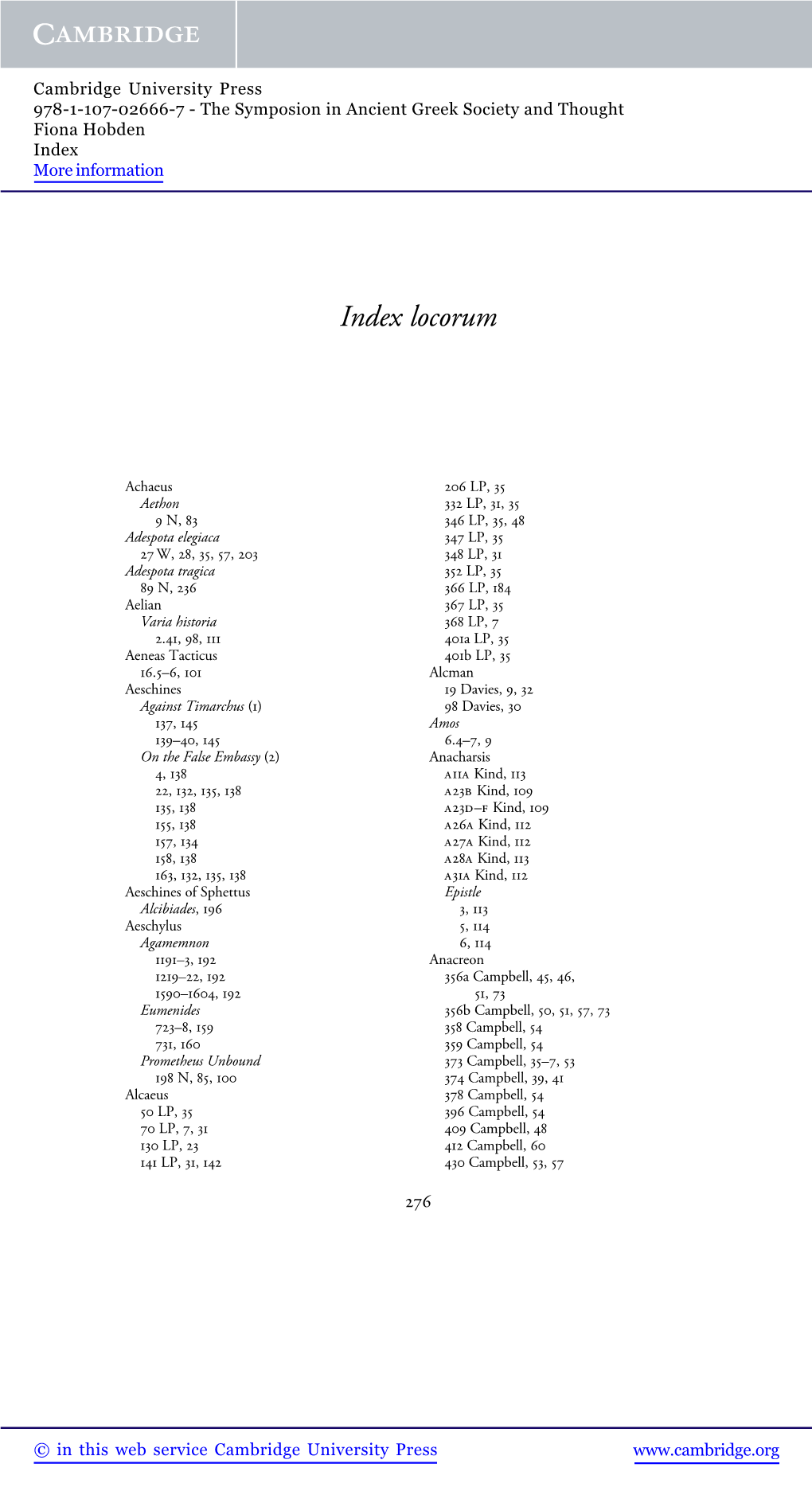

Index Locorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simon the Shoemaker

SIMON THE SHOEMAKER John Sellars 1399 3RD AVENUE -MANHATTAN- SIMON SHOE REPAIR -1- The name “Simon the Shoemaker” is not one im- mediately familiar to specialists in ancient philoso- 1 phy, let alone to students of philosophy in general. This may well be due, in part, to the tendency of many scholars both past and present to deny his historical reality altogether. Ancient sources refer to a Simon who, it is said, was an associate of Socrates and who ran a shoe shop on the edge of the Athenian agora where Socrates used to come to engage in philosophical discussions with Simon while he worked.2 However, the fact that neither Plato nor Xenophon mentions Simon has often been cited as an argument against his very existence. Moreover, it is reported that the Socratic philosopher Phaedo wrote a dialogue entitled Simon, and thus it has been sug- gested that the later “Simon legend” derived ultimately from a literary character created by Phaedo.3 The situation has somewhat changed since the discovery of the remains of a shop near the Tholos on the southwestern edge of the agora, the floor scattered with hobnails, containing a base from a pot with the word “Simon’s” inscribed upon it.4 Ar- chaeologists commenting upon this discovery have been keen to identify its owner with the Simon mentioned in the literary sources as a companion of Socrates, but scholars primarily concerned with ancient philosophy have tended to remain doubtful.5 Simon’s reputation relies principally upon the claim made by Diogenes Laertius that Simon was the first to write “Socratic dialogues.”6 Diogenes reports that these were also known as “shoemaker’s dialogues” or simply “shoemaker’s.” These, Diogenes says, were notes of actual conversations that Simon had had with Socrates rather than literary compositions. -

A History of Cynicism

A HISTORY OF CYNICISM Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com A HISTORY OF CYNICISM From Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. by DONALD R. DUDLEY F,llow of St. John's College, Cambrid1e Htmy Fellow at Yale University firl mll METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street, Strand, W.C.2 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com First published in 1937 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE research of which this book is the outcome was mainly carried out at St. John's College, Cambridge, Yale University, and Edinburgh University. In the help so generously given to my work I have been no less fortunate than in the scenes in which it was pursued. I am much indebted for criticism and advice to Professor M. Rostovtseff and Professor E. R. Goodonough of Yale, to Professor A. E. Taylor of Edinburgh, to Professor F. M. Cornford of Cambridge, to Professor J. L. Stocks of Liverpool, and to Dr. W. H. Semple of Reading. I should also like to thank the electors of the Henry Fund for enabling me to visit the United States, and the College Council of St. John's for electing me to a Research Fellowship. Finally, to• the unfailing interest, advice and encouragement of Mr. M. P. Charlesworth of St. John's I owe an especial debt which I can hardly hope to repay. These acknowledgements do not exhaust the list of my obligations ; but I hope that other kindnesses have been acknowledged either in the text or privately. -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

Traces of Cynic Monotheism in the Early Roman Empire*

ACTA CIASSICA LI (2008) 1-20 ISSN 0065-1141 ARTICLES • ARTIKELS TRACES OF CYNIC MONOTHEISM IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE* P.R. Bosman Univel sity of South Africa ABSTRACT The ancient Cynics rejected traditional religion, themselves on first appearances endorsing either atheism or agnosticism. But their criticism may also have stemmed from a radical monotheism as voiced by Antisthenes. After briefly discussing imperial Cynics and their views on religion, the article argues that the 4th letter of Pseudo-Heraclitus and the Geneva Papyrus inv. 271, Cynic texts from the Early Empire, are not contrary to the essentials of the philosophy and may represent late Hellenistic forms of the Antisthenic tradition in portraying Cynic-type sages mediating between humankind and the God of nature. Introduction Cynic philosophy's roots go back to the 4th century BC, but it experienced a revival approximately simultaneous with the dramatic rise of Christianity. The two movements had much in common, not least their shared criticism of traditional Greco-Roman religion. 1 Two fundamental forces driving early Christian rejection of popular religion were belief in the one God of Judaism and a close association of his will with the rules for righteous living. It may be asked whether anything similar can be found in the Cynicism of that era. Some sources indeed suggest that the Cynics - traditionally focussing exclusively on ethics - were prepared to link their way of life to belief in a single God who provides or communicates the principles of correct conduct to the Cynic sage.2 * I wish to thank the referees of Acta Classica for valuable comments and corrections to this text. -

Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 BC Exiles

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1971 Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 B. C. Exiles: A Case of Political Irrationality Peter Karavites Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Karavites, Peter, "Problems in Athenian Democracy 510-480 B. C. Exiles: A Case of Political Irrationality" (1971). Dissertations. Paper 1192. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1192 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1971 Peter. Karavites PROBLEMS IN ATHENIAN DEMOCRACY 510-480 B.C. EXILES A Case of Political Irrationality A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty o! the Department of History of Loyola University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy b;y Peter Karavites ?ROBLEt'.n IN ATP.EHIA:rT n:s::ocRACY 5'10-480 n.c. EXIL:ffi: A case in Politioal Irrationality Peter·KARAVIT~ Ph.D. Loyola UniVGl'Sity, Chicago, 1971 This thesis is m attempt to ev"aluate the attitude of the Athenian demos during the tormative years of the Cleisthenian democracy. The dissertation tries to trace the events of the period from the mpul sion of Hippian to the ~ttle of Sal.amis. Ma.tural.ly no strict chronological sequence can be foll.amtd.. The events are known to us only f'ragmen~. some additional archaeological Wormation has trickled dcmn to us 1n the last tro decad.all 11h1ch shed light on the edating historical data prO\Tided ma:1nly by Herodotus md Arletotle. -

Cynicism As a Way of Life: from the Classical Cynic to a New Cynicism

Akropolis 1 (2017) 33–54 Dennis Schutijser* Cynicism as a way of life: From the Classical Cynic to a New Cynicism Introduction Both within and outside the world of academic philosophy, art of living has been increasingly in the spotlight. Objectives such as success, pleasure and happi- ness are expressly validated in contemporary society, but more philosophically val- id objectives such as cultivation of the soul also receive ample attention. On the other side, within academic philosophy, the question for the art of living has also been receiving increasing attention.1 This revival could arguably be led back to Mi- chel Foucault’s genealogical return to antiquity in the second and third parts of his History of Sexuality, in turn undoubtedly influenced by the works of Pierre Hadot. Especially classical philosophy has proven a rich source of investigation and inspi- ration for a philosophy of the art of living. Many currents in ancient philosophy ac- tually proposed different ways of living, based on different values and articulated in different practices.2 One of the central currents throughout a large part of antiquity was Cyn- icism. This school is accompanied with a number of methodological difficulties. Not least of all, today’s connotation of the name Cynicism is radically different from its classical origins. Today, being a cynic is associated with a depreciative at- titude, intended to insult and offend, rather than being concerned with any phil- osophical foundation. A further complication is that little is known directly of classical Cynicism, and what we do know often comes from anecdotes and stories written down by posterity, and not from actual first hand sources of substantial profundity. -

Pindar. Olympian 7: Rhodes, Athens, and the Diagorids*

«EIKASMOS» XVI (2005) Pindar. Olympian 7: Rhodes, Athens, and the Diagorids* 1. Introduction Over the last century and a half numerous articles, notes, and chapters of books, several commentaries, and two scholarly monographs have been devoted to Olympian 71. These have established the ode’s ring-compositional structure and its conceptual responsions, and they have clarified many of its linguistic and literary difficulties, although not without some ongoing controversy in both areas2. How- ever, the historical dimensions of Olympian 7 have not fared so well. They have sometimes been neglected, and sometimes dismissed out of hand3. The reception accorded to Chapter 8 of Bresson 1979, Pindare et les Eratides, a major investi- * A preliminary version of this paper was presented to the Departmental Research Seminar of the School of Classics, University of Leeds, on 30 April 1997, and a revised Italian version to the Dipartimento di Filologia Classica e Medievale of the Università degli Studi di Parma on 12 May 2004 at the kind invitation of Prof. Gabriele Burzacchini. I thank all those who attended these presentations and who contributed to the subsequent discussions. In the interval between the two presentations, I benefited from the stimulus provided by Dr. Barbara Kowalzig’s paper Fire, Flesh, Foreigners and Fruit: Greek Athena on Rhodes?, given at the conference Athena in the Classical World in Oxford on 2 April 1998. I am further grateful to Prof. Douglas L. Cairns, Mr. J. Gordon Howie, Prof. John Marincola, and Prof. Ian Rutherford for their valuable critiques of earlier versions of this paper and their additional suggestions. -

The Invisibility of Juvenal James Uden Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

The Invisibility of Juvenal James Uden Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 2011 James Uden All rights reserved. ABSTRACT The Invisibility of Juvenal James Uden This dissertation offers a reading of Juvenal’s Satires. It maintains that Juvenal consciously frustrates readers’ attempts to identify his poetic voice with a single unitary character or persona. At the same time, it argues that Juvenal’s poems are influenced in both form and theme by cultural trends in the early second century. The arguments staged in these poems constitute a critique of aspects of Roman intellectual culture in the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian. Contents Preface 1. Provoking the Charge: Epic Poet and Reticent Informer in Satire One The Recitation Hall (Part One) The Paradox of Contemporary Epic The Satirist as Delator The Crisis of Criticism Satiric Voices in Tacitus’ Dialogus de Oratoribus The Recitation Hall (Part Two) 2. The Invisibility of Juvenal ‘Atopic Topology’: The Thirteenth Oration of Dio Chrysostom Juvenal’s Second Satire: Strategies for Speech and Disguise Secrecy and Violence in Satire Nine 3. Satire Four: Playing the Panegyrist The Art of Exaggeration The Emperor over Nature Natural Reversal and Fish Savagery The Perils of Panegyrical Speech i 4. Cynic Philosophy and Ethical Education in Satires Ten and Fourteen Debasing the Coinage The Laugh of Democritus and the Cynic Ideal Satire Fourteen: The Domestication of Ethical Teaching 5. Satire Twelve: Repetition and Sacrifice in Hadrianic Rome Horatian Ritual and the “New Augustus” Substitution and Sacrifice: Animals and Humans in Satire Twelve The Gods and their Captatores Reading across Books: Atheism and Superstition in Satire Thirteen Appendix: Martial 12.18 and the Dating of Juvenal’s First Book ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks must go first to Gareth Williams, friend and mentor for the past half-decade. -

Reading 1 Corinthians with the Augustan Marriage Laws

Paul on Marriage and Singleness: Reading 1 Corinthians with the Augustan Marriage Laws by David Alan Reed A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology of the University of St. Michael’s College and the Biblical Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College © David Alan Reed 2013 Paul on Marriage and Singleness: Reading 1 Corinthians 7 with the Augustan Marriage Laws David Wheeler-Reed Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2013 Abstract This thesis examines what happens if Paul’s directives to married and single persons in 1 Corinthians 7 are read in light of Corinth’s Roman cultural context. It seeks to make analogical comparisons between Paul’s directives in 1 Corinthians 7 and the Augustan Marriage Laws known as the Lex Iulia and Lex Papipa Poppaea. When Paul’s directives are read with the Augustan marriage laws, a very complex picture of Paul develops. First of all, against “empire- critical” readers of Paul, the apostle is not entirely against all aspects of the Roman empire. Instead, this thesis demonstrates that as a colonized individual himself, Paul was a “hybrid” figure, who simultaneously borrowed from and fought against many of the ideas of Roman imperialism. Second, this work shows that when Paul disagreed with the Augustan marriage legislation, he did so mainly with respect to what it had to say about widows. In fact, Paul’s directives to widows are very similar to the thoughts of many other Roman moralists in the first- century CE. -

Selfdefinition Among the Cynics

From: Paul and the Popular Philosophers SelfDefinition among the Cynics Abraham Malherbe The Cynics and the Cynicism of the first century A.D. are known to us for the most part through Stoic interpreters, and the temptation is great, on the basis of Seneca's account of Demetrius, Musonius Rufus, Epictetus, and Dio Chrysostom, to draw a picture of Cynicism which obscures the differences between Stoicism and Cynicism and among the Cynics themselves. In the second century, the diversity among the Cynics emerges more clearly as such personalities as Oenomaus of Gadara, Demonax, and Peregrinus Proteus appear on the scene. Unfortunately, only fragments of Oenomaus's writings have been preserved, and only a few comments, mostly negative, are made about him by Julian, and we are largely but not wholly dependent on Lucian's interpretations of Demonax and Peregrinus for information about them. It is therefore fortunate that in the Cynic epistles we do have primary sources for the sect in the Empire. These neglected writings are more than the school exercises they have been thought to be, and enable us to determine the points at issue among the Cynics themselves. The Definition of Cynicism Diogenes Laertius already experienced difficulty in describing common Cynic doctrine, and records that some considered it, not a philosophical school (hairesis), but a way of life (Lives of Eminent Philosophers 6.103). He seems to incline to the view that it is a philosophical school, but notes that Cynics dispensed with logic and physics, and confined themselves to ethics. Cynics have generally been perceived as having an aversion to encyclopaedic learning and placing no premium on education in the pursuit of virtue. -

Pindar and the Poetics of Autonomy: Authorial Agency in Pindar’S Fourth Pythian Ode

I PINDAR AND THE POETICS OF AUTONOMY: AUTHORIAL AGENCY IN PINDAR’S FOURTH PYTHIAN ODE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dennis Robert Alley May 2019 II ©2019 Dennis Robert Alley III PINDAR AND THE POETICS OF AUTONOMY: AUTHORIAL AGENCY IN PINDAR’S FOURTH PYTHIAN ODE Dennis Robert Alley Cornell University 2019 Over the last decade a growing number of scholars have questioned the veracity of the longstanding commission-fee model which placed the Greek lyric poet Pindar in the thrall of various aristocratic patrons to secure his pay. This seismic shift in our view on Pindar’s composition reveals manifold new questions to explore in its wake. What happens to our understanding of the 45 extant odes and extensive fragments, when, for example, angling for commission no longer mandates procrustean generic strictures? How do we understand praise poetry if not as exclusively solicited and sold? Where do we even begin examining the odes under this new model? Pindar and the Poetics of Autonomy suggests one ode in particular has suffered from the rigidity of scholarly expectations on commission and genre. In the corpus of Pindaric epinicia, Pythian Four, written around 462 for Arcesilaus the fourth of Cyrene, is conspicuously anomalous. At 299 exceptionally long lines, the poem is over twice as long as the next longest ode. While most epinicia devote considerable space in their opening and closing sections to celebrating the present victory, Pythian Four makes only one clear mention of it. -

JESUS AS DIOGENES? REFLECTIONS on the CYNIC JESUS THESIS PAUL RHODES EDDY Bethel College, St

JBL 115/3(1996) 449469 JESUS AS DIOGENES? REFLECTIONS ON THE CYNIC JESUS THESIS PAUL RHODES EDDY Bethel College, St. Paul, MN 55112 The last two decades or so have witnessed an unforeseen explosion of scholarly interest in the quest for the historical Jesus. The vestigial skepticism of the No Quest period and the halting steps of the New Quest have largely given way to renewed enthusiasm with regard to the historical recovery of Jesus. It is in this light that scholars have begun to talk about a new "renais- sance" in Jesus research and the emergence of a Third Quest.' The results of this recent push, however, have been anything but uniform. Jesus of Nazareth has been variously tagged as a Galilean holy man,%n eschatological prophet,3 an occultic magician? an innovative rabbi? a trance-inducing psychotherapist,fi See respectively M. J. Borg, "A Renaissance in Jesus Studies," in hisJesus in Contemporary Scholarship (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994) 3-17; S. Neill and N. T. Wright, Interpretation of the New Testament, 1861-1986 (2d ed.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988) 379-403. For other helpful assessments of recent Jesus research, see J. H. Charlesworth, "Jesus Research Expands with Chaotic Creativity," in Images of Jesus Today (ed. J. Charlesworth and W. Weaver; Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994) 1-41; W. Telford, "Major Trends and Interpretive Issues in the Study of Jesus," in Studying the Historical Jesus: Eualuations of the State of Cuwent Research (ed. B. Chilton and C. A. Evans; NTTS 19; LeidenfNew York: Brill, 1994) 33-74; N.