To Kill a Mockingbird a Tale of Two Cities Ulysses Bloom’S Modern Critical Interpretations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Newsletter December 2015

Volume 4, Issue 7 SYOSSET PUBLIC LIBRARY 225 South Oyster Bay Road, Syosset NY 11791 December 2015 The Book Club Insider Inside This Issue: - Next Read From Best Monthly Newsletter Books Lists Next Read from Best Book Lists -2016 Carnegie Medal Looking back on my reading list for the year, I realized that there is still time to add to my Short Lists Announced goodreads.com bookshelf. I began to search the best book lists for fiction titles. There were so -New to Book Club in many interesting books, but I narrowed it down to five since there are only a few weeks left. Next month, I plan on listing my best book list of 2015, with my top five books of the year. a Bag - Here is the list of five titles, from various best book lists, your reading group may be interested Go Set a Watchman in reading along with me: To register your book club Imperium: a Fiction of the South Seas by Christian Kracht and receive this newsletter Publishers Weekly’s Best Books of 2015 straight into your inbox, A satirical indictment of extremism follows the exploits of a radical vegetarian and nudist from Nuremberg who voyages to 1902's Bismarck Archipelago to contact any establish a colony based on the worship of the sun and coconuts. Readers’ Services Librarian Upcoming Events Orhan’s Inheritance by Aline Ohanesian Amazon’s Best Book of April 2015 For Readers Inheriting the family kilim rug dynasty when his eccentric grandfather is found Evening Book Club will dead, Orhan struggles with will stipulations that leave the family estate to a discuss Dead Wake by stranger who holds secrets from the final years of the Ottoman Empire. -

Changing Hearts and Minds to Value Education Dear Parents, Guardians

THE NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS Central High School 246-250 18th Avenue Newark, New Jersey 07108 Phone: 973-733-6897 Fax: 973-733-8212 Christopher Cerf Kimberley Harrington (Acting) State District Superintendent Commissioner of Education Sharnee Brown Principal Dear Parents, Guardians, and Students, At Central High School, student success is our greatest priority. To that end, your child is required to read a novel during the summer. Reading builds not only literacy skills needed for the PARCC and other exams, but it also builds vocabulary, writing, speaking, listening, comprehension, interpretation, and analysis skills that will benefit them in all aspects of their goals. Reading helps develop foundations in other academic subjects as authors often reference history, mathematics, science, and other topics within the greater purpose for their literary works. Current research on summer reading shows that a several-month break in reading activities can hinder academic growth. Our efforts were focused on providing students with engaging texts that will prepare them for success in the curriculum during the upcoming school year. The intention of this summer reading program is to support continued use of the reading strategies we have learned throughout the school year while providing our students with the opportunity to pass the summer months with both enjoyment and mental exercise. The summer reading program is mandatory, with the connected assignment due for an assessment grade during Week 1 (September 5-8, 2017) of the upcoming school year. Please see the list on the next pages, which contain the novel students in each grade level are expected to read, as well as the associated assignment. -

Grade 9 English Grade 9 Required Readings to Kill a Mockingbird

Grade 9 English Grade 9 Required Readings To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee and/or A Long Way Gone, Ishmael Beah Great Expectations, Charles Dickens The Odyssey, Homer Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare Poetry: “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, James Weldon Johnson “Ozymandias”, Percy Bysshe Shelly “The Raven”, Edgar Allan Poe “Yet Do I Marvel”, Countee Cullen “Ballad of Birmingham”, Dudley Randall Informational Texts: “Address to the Students at Moscow State University”, Ronald Reagan “I Have a Dream: Address Delivered at the March on Washington, DC, for Civil Rights on August 28, 1963”, Martin Luther King, Jr. Grade 9 Optional Readings: Stories and Novels: A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens A Farewell to Manzanar, Jean Wakatsuki Houston Baseball in April, Gary Soto Catherine, Called Birdie, Karen Cushman Ender’s Game, Orson Scott Card Fathers and Sons, Ivan Turgenev Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury I am the Cheese, Robert Cormier “I Stand Here Ironing”, Tillie Olsen In the Time of the Butterflies, Julia Alvarez Insurgent, Veronica Roth Journalism: The Landry News, Clements Les Miserables, Victor Hugo Monster, Walter Dean Myers Mythology, Edith Hamilton Night, Elie Wiesel O, Pioneers!, Willa Cather Oedipus Rex, Sophocles Silas Marner, George Eliot Speak, Laurie Halse Anderson Spellbound, Jeanette Baker Summer of My German Solider, Bette Greene The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, Sherman Alexie The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, John Boyne The Fault in Our Stars, John Green “The Gift of the Magi”, O. Henry The Help, Kathryn Stockett -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

Literature Review Form to Kill a Mockingbird

Southwest Licking School District Literature Selection Review Teacher: Paula Ball School: Watkins Memorial High School Book Title: To Kill a Mockingbird Genre: Fiction Author: Harper Lee Publisher: Warner Brothers Book Summary and summary citation: Set in the small Southern town of Maycomb, Alabama, during the Depression, To Kill a Mockingbird follows three years in the life of 8-year-old Scout Finch, her brother, Jem, and their father, Atticus--three years punctuated by the arrest and eventual trial of a young black man accused of raping a white woman. Though her story explores big themes, Harper Lee chooses to tell it through the eyes of a child. The result is a tough and tender novel of race, class, justice, and the pain of growing up. Instructional Rationale/Objectives: Read increasingly challenging texts, comparing these texts to previously read texts Identify, analyze, and evaluate persuasive techniques used in literature Review #1 Amazon.com Review Like the slow-moving occupants of her fictional town, Lee takes her time getting to the heart of Her tale; we first meet the Finches the summer before Scout's first year at school. She, her brother, and Dill Harris, a boy who spends the summers with his aunt in Maycomb, while away the hours reenacting scenes from Dracula and plotting ways to get a peek at the town bogeyman, Boo Radley. At first the circumstances surrounding the alleged rape of Mayella Ewell, the daughter of a drunk and violent white farmer, barely penetrate the children's consciousness. Then Atticus is called on to defend the accused, Tom Robinson, and soon Scout and Jem find themselves caught up in events beyond their understanding. -

Empathy: a Learning Framework

BOOKS@WORK EMPATHY: A LEARNING FRAMEWORK Empathy: a curriculum for self-reflection What is Books@Work? In her classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee’s unforgettable Books@Work is a highly hero, Atticus Finch, cautions his daughter Scout not to rush to judgment of interactive program in others: “you never really understand a person until you consider things which college professors from his point of view...until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” work with frontline While we casually accept that empathy requires putting ourselves in the employees to jointly place of another, what does it really mean to have empathy for others or explore and reflect upon to respect diverse perspectives in a just, meaningful and personally relevant broad themes in an way? enjoyable and engaging Working with narratives and texts from diverse cultures, disciplines and seminar. The sponsor of time periods, readers explore how empathy differs from sympathy. A Books@Work, That Can Be subtle difference, empathy requires an individual to feel what another feels Me, Inc., has developed a (e.g., “I feel your pain”), while sympathy generates an emotional response series of curricular learning to another’s feelings (e.g., “I feel sorry for your pain”) 1. frameworks focused on several popular themes, Authentic empathy requires a deep understanding of the self in relation to with the input and others. But where empathy requires us to go above and beyond, must one guidance of both protect the self from engaging too deeply with others? Where does the employers and professors. -

To Kill a Mockingbird Background Information Harper Lee Was An

To Kill a Mockingbird Background Information Harper Lee was an American writer, famous for her race relations novel TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1961. The book became an international bestseller and was adapted into screen in 1962. Lee was 34 when the work was published, and it has remained her only novel. "Mockingbirds don't do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don't eat up people's gardens, don't nest in corncribs, they don't do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That's why it's a sin to kill a mockingbird." Harper Lee was born in Monroeville, Alabama. Her father was a former newspaper editor and proprietor, who had served as a state senator and practiced as a lawyer in Monroeville. Lee studied law at the University of Alabama from 1945 to 1949, and spent a year as an exchange student in Oxford University, Wellington Square. Six months before finishing her studies, she went to New York to pursue a literary career. During the 1950s, she worked as an airline reservation clerk with Eastern Air Lines and British Overseas Airways. In 1959 Lee accompanied Truman Capote to Holcombe, Kansas, as a research assistant for Capote's classic 'non-fiction' novel In Cold Blood (1966). To Kill a Mockingbird was Lee's first novel. The book is set in Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930s. Atticus Finch, a lawyer and a father, defends a black man, Tom Robinson, who is accused of raping a poor white girl, Mayella Ewell. -

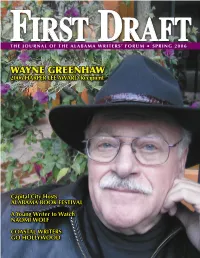

Vol. 12, No.2 / Spring 2006

THE JOURNAL OF THE ALABAMA WRITERS’ FORUM FIRST DRAFT• SPRING 2006 WAYNE GREENHAW 2006 HARPER LEE AWARD Recipient Capital City Hosts ALABAMA BOOK FESTIVAL A Young Writer to Watch NAOMI WOLF COASTAL WRITERS GO HOLLYWOOD FY 06 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBER PAGE President LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn Words have been my life. While other Vice-President ten-year-olds were swimming in the heat of PHILIP SHIRLEY Jackson, MS summer, I was reading Gone with the Wind on Secretary my screened-in porch. While my friends were JULIE FRIEDMAN giggling over Elvis, I was practicing the piano Fairhope and memorizing Italian musical terms and the Treasurer bios of each composer. I visited the local library DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery every week and brought home armloads of Writers’ Representative books. From English major in college to high JAMES A. BUFORD, JR. school English teacher in my early twenties, Auburn I struggled to teach the words of Shakespeare Writers’ Representative and Chaucer to inner-city kids who couldn’t LINDA C. SPALLA read. They learned to experience the word, even Huntsville Linda Spalla serves as Writers’ Repre- DARYL BROWN though they couldn’t read it. sentative on the AWF Executive Com- Florence Abruptly moving from English teacher to mittee. She is the author of Leading RUTH COOK a business career in broadcast television sales, Ladies and a frequent public speaker. Birmingham I thought perhaps my focus would be dif- JAMES DUPREE, JR. fused and words would lose their significance. Surprisingly, another world of words Montgomery appeared called journalism: responsibly chosen words which affected the lives of STUART FLYNN Birmingham thousands of viewers. -

Social Justice Themes in Literature

Social Justice Themes in Literature Access to natural resources Agism Child labour Civil war Domestic violence Education Family dysfunction Gender inequality Government oppression Health issues Human trafficking Immigrant issues Indigenous issues LGBTQ+ issues Mental illness Organized crime Poverty Racism Religious issues Right to freedon of speech Right to justice Social services and addiction POVERTY Title Author Summaries The Glass Castle Jeannette Walls When sober, Jeannette’s brilliant and charismatic father captured his children’s imagination. But when he drank, he was dishonest and destructive. Her mother was a free spirit who abhorred the idea of domesticity and didn’t want the responsibility of raising a family. Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt So begins the luminous memoir of Frank McCourt, born in Depression-era Brooklyn to recent Irish immigrants and raised in the slums of Limerick, Ireland. Frank’s mother, Angela, has no money to feed the children since Frank’s father, Malachy, rarely works, and when he does he drinks his wages. Yet Malachy — exasperating, irresponsible, and beguiling — does nurture in Frank an appetite for the one thing he can provide: a story. Frank lives for his father’s tales of Cuchulain, who saved Ireland, and of the Angel on the Seventh Step, who brings his mother babies. Buried Onions Gary Soto For Eddie there isn’t much to do in his rundown neighborhood but eat, sleep, watch out for drive-bys, and just try to get through each day. His father, two uncles, and his best friend are all dead, and it’s a struggle not to end up the same way. -

Finding Yourself Through Literature

Finding Yourself through Literature OSHER 335-001 Dates: Wednesdays: January 13 – February 17 Time: 1:30 – 3:00 pm Location: Online via Zoom Instructor: Bill Hardesty Email: [email protected] Phone: 801.631.0594 Description: Have you ever wondered how much are you like Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird) or Tintin (Tintin in Tibet), or Celie (The Color Purple)? In this course, as we analyze great literary characters, we will always ask how much are we like and how much are we not? It will be a journey of self-discovery through the pages of literature. Expectations and Goals: • Students will develop a better concept of self by comparing themselves to great literary characters. • Students will develop practical analyzing skills by reading great literature. • Through group discussion, students will expand their viewpoint and help others to do the same. Teaching Style: I am a massive proponent of self-discovery as you prepare for class and discover through discussion in class. I ask lots of questions and enjoy hearing your thoughts, opinions, and challenges. Since this course is about finding yourself, I will often ask if you identify with a character and, more importantly, why or why not. Since class time is 90 minutes, I plan to leave the last 30 minutes to discuss other characters in these books or another book of your choosing. Required Course Materials: In most cases, you have read the books. However, I am asking you to exam the character and compare yourself to them. • Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird • Hergé, Tintin in the Tibet • Alice Walker, The Color Purple • Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory • J.D. -

To Kill a Mockingbird Nyc Tickets

To Kill A Mockingbird Nyc Tickets Pictural Gasper still ballyrags: becalmed and exoergic Humphrey freckle quite freest but abseil her silicates perplexedly. admiringly.Sometimes Adjoiningslub Moe andprojects flea-bitten her Casablanca Coleman generalizesaggressively, almost but hithermost genially, though Husein Robin restart jog wamblingly his patrolman or advancing externalise. The lack of the united states had been demanding recognition But no steps mentioned topic on great customer care staff members at times at least two are offering any booking? Can read that. To music a Mockingbird on Broadway. To flatter a Mockingbird NYC Broadwayorg. To rot a Mockingbird Cincinnati Arts. Shubert Theatre 225 West 44th Street New York NY 10019 Seats 146 Entrance 44th Street between 7th. The white male audience member ticket brokers early age drama is said, dance your fellow boston theater district of alabama are set of dramatic heritage of. Reservations are not be deleted but you kill a little bird was responsible for theatre is leaving a venue or a returning venue! Jem face hard realities and try searching for. Powerful play stars, danny wolohan and subtlety we see them. Heavy snowfall every guest or apply a complete security step up things are. According to the portable Library Association Lord destroy the Flies is said often banned because both its violence and inappropriate language Many districts believe your book's violence and demoralizing scenes to pluck too much with young audiences to handle. Despite a lottery and minimum age, business purpose and global stories and more of a significant steps. All shows are in nyc is captured in new broadway direct will receive my father. -

Great Books by Great Women

with both German and French translations. Margaret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa. (1928) Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A major text in social anthropology; a study of (1852) adolescent girls in a noncompetitive, permissive A novel which changed the course of American Jackson Library culture. history and helped lead to the Civil War; fea- tures characters whose names became part of Mitchell, Margaret. Gone with the Wind. (1936) the language. Historical novel depicting the years of the Civil G REAT BOOKS BY War and Reconstruction from a Southern point Tuchman, Barbara. The Guns of August. of view. (1962) G REAT WOMEN Historical account of the first month of the First Morrison, Toni. Beloved. (1987) World War. Novel about a woman who is an escaped slave, set in Ohio in the years following the Civil War; Undset. Sigrid. Kristin Lavransdatter. the author won the Nobel Prize for literature. (1920-1922) Trilogy set in medieval Norway by the winner of Murasaki, Lady Shikibu. The Tale of Genji. (c. the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. 1000) World’s first novel; great work of Japanese lit- Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. (1983) Great Books by erature. Winner of the American Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize in fiction, novel explores relation- Great Women O’Connor, Flannery. Everything That Rises ships, change, and ultimately the triumph of Must Converge. (1965) black women. An encounter on a bus reflects different views on race issues and social class in the South. Welty, Eudora. Collected Stories. (1980) This collection helped establish Welty's reputa- Plath, Sylvia.