The Anatomical “Core”: a Definition and Functional Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linked: Breathing & Postural Control

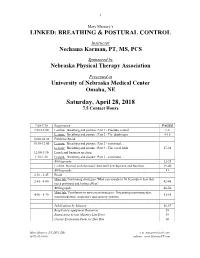

i Mary Massery’s LINKED: BREATHING & POSTURAL CONTROL Instructor Nechama Karman, PT, MS, PCS Sponsored by Nebraska Physical Therapy Association Presented at University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE Saturday, April 28, 2018 7.5 Contact Hours 7:00-7:30 Registration PAGES 7:30-10:00 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 1 - Pressure control 1-8 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 2 - The diaphragm 9-16 10:00-10:30 Exhibitor Break 10:30-12:00 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 2 - continued… Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 3 - The vocal folds 17-21 12:00-1:30 Lunch and business meeting 1:30-2:30 Lecture: Breathing and posture: Part 3 - continued… Bibliography 22-28 Lecture: Normal and abnormal chest wall development and function 29-40 Bibliography 41 2:30 - 2:45 Break Mini-lab: Positioning strategies: What can you do in 90 Seconds or less that 2:45 - 4:00 42-45 has a profound and lasting effect? Bibliography 46-50 Mini-lab: Ventilatory or movement strategies: Integrating neuromuscular, 4:00 - 5:30 51-55 musculoskeletal, respiratory and sensory systems Publications by Massery 56-57 Respiratory equipment Resources 58 Instructions to join Massery List Serve 59 Course Evaluation Form for Day One 60 Mary Massery, PT, DPT, DSc e-m: [email protected] (847) 803-0803 website: www.MasseryPT.com ii COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will challenge the practitioner to make a paradigm shift: connecting breathing mechanics and postural control with management of trunk pressures. Through Dr. Massery’s model of postural control (Soda Pop Can Model), the speaker will link breathing mechanics with motor and physiologic behaviors (a multi-system perspective). -

Vertebral Column and Thorax

Introduction to Human Osteology Chapter 4: Vertebral Column and Thorax Roberta Hall Kenneth Beals Holm Neumann Georg Neumann Gwyn Madden Revised in 1978, 1984, and 2008 The Vertebral Column and Thorax Sternum Manubrium – bone that is trapezoidal in shape, makes up the superior aspect of the sternum. Jugular notch – concave notches on either side of the superior aspect of the manubrium, for articulation with the clavicles. Corpus or body – flat, rectangular bone making up the major portion of the sternum. The lateral aspects contain the notches for the true ribs, called the costal notches. Xiphoid process – variably shaped bone found at the inferior aspect of the corpus. Process may fuse late in life to the corpus. Clavicle Sternal end – rounded end, articulates with manubrium. Acromial end – flat end, articulates with scapula. Conoid tuberosity – muscle attachment located on the inferior aspect of the shaft, pointing posteriorly. Ribs Scapulae Head Ventral surface Neck Dorsal surface Tubercle Spine Shaft Coracoid process Costal groove Acromion Glenoid fossa Axillary margin Medial angle Vertebral margin Manubrium. Left anterior aspect, right posterior aspect. Sternum and Xyphoid Process. Left anterior aspect, right posterior aspect. Clavicle. Left side. Top superior and bottom inferior. First Rib. Left superior and right inferior. Second Rib. Left inferior and right superior. Typical Rib. Left inferior and right superior. Eleventh Rib. Left posterior view and left superior view. Twelfth Rib. Top shows anterior view and bottom shows posterior view. Scapula. Left side. Top anterior and bottom posterior. Scapula. Top lateral and bottom superior. Clavicle Sternum Scapula Ribs Vertebrae Body - Development of the vertebrae can be used in aging of individuals. -

Gross Anatomy ABDOMEN/SESSION 4 Dr. Firas M. Ghazi Posterior

Gross Anatomy ABDOMEN/SESSION 4 Dr. Firas M. Ghazi Posterior Abdominal Wall and the Diaphragm PAW : Posterior Abdominal Wall Curricular Objectives By the end of this session students are expected to: Practical 1. Identify the bones forming the PAW and their main markings 2. Distinguish the muscles forming the PAW and their fascial coverings 3. Trace the nerves of the PAW to their terminations 4. Identify the diaphragm and discriminate structures arising from its vertebral origin 5. Locate the major foramina of the diaphragm and the structures they transmit 6. Identify the retroperitoneal organs related to PAW Theory 1. State the framework of PAW 2. Name the bones forming the PAW and describe their main markings 3. Outline the muscles forming the PAW, their attachment and actions 4. Define the para-vertebral gutter and list the retroperitoneal organs related to it 5. Acknowledge the close relation of abdominal aorta to AAW 6. List the nerves related to PAW and their main distribution 7. Review the cremasteric reflex and acknowledge its physiological importance 8. Recall the patellar reflex and follow its pathway 9. Recall the attachment of the diaphragm and describe its vertebral origin 10. Underline the major foramina of the diaphragm and the structures they transmit 11. Review the innervation of diaphragm and the possible sites of referred pain 12. Summarize the fascial and peritoneal linings of the abdominal cavity Selected references and suggested resources Clinical Anatomy by Regions, Richard S. Snell, 9th edition Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, 13th Edition McMinn's Clinical Atlas of Human Anatomy, 7th Edition Anatomy for Babylon medical students (facebook page) Human Anatomy Education (facebook page) Human anatomy education (you tube channel) This session has been reviewed by Anatomy team at the Department of Anatomy and Histology/ College of Medicine/ University of Babylon/ 2016 Session check list Clinical importance Irritation of peritoneum on PAW can stimulate the related nerves and result in characteristic clinical manifestations. -

Isometric Contractions and the Plank Same Length Muscles Worked

Isometric Contractions and the Plank If you've ever seen a mime trying to escape his invisible box, you've seen a playful example of an isometric contraction. Isometric exercises are strength-training exercises that involve the contraction of a muscle against an immovable resistance. While the mime's resistance is imaginary, you use the floor for resistance when doing an isometric plank. The isometric plank exercise provides core stability, improves posture and protects your lower back. Same Length “Iso” means same and “metric” means length, so isometric literally means “same length.” The static tension of isometric exercise strengthens the muscles at the same length -- in the position in which they are held. This can be beneficial when rehabilitating an injured joint or as a technique to improve fluid movement by overcoming weaknesses within a range of motion. It's also a good exercise technique for training the core muscles, which often must remain stable as your arms and legs move. Because isometric exercises don't move the joint through a full range of motion, you should hold isometric contractions in various positions and at varying angles to obtain maximum benefit. Muscles Worked To safely maintain the plank pose, you have to pull your belly button up toward your spine. This action, called abdominal hollowing, activates the deeper, stabilizing muscles of the core. The muscles that benefit most from an isometric plank are the transverse abdominis, obliques, rectus abdominis and erector spinae. Depending on the position you hold, the plank pose may also strengthen muscles in your wrists, arms, shoulders, chest, feet, legs and buttocks. -

Bilateral Scarpa's Fascia Advancement Flaps to Improve The

Egypt, J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg., Vol. 35, No. 1, January: 133-140, 2011 Bilateral Scarpa’s Fascia Advancement Flaps to Improve the Waistline in Abdominoplasty WAEL M. ELSHAER, M.D.*; SAMEH ELNOAMANI, M.D.** and HOSSAM HOSNI, M.D.** The Department of Plastic and General surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Bani-Suef * and Cairo** Universities. ABSTRACT better sculpting or to hide the abdominal scar [1] . With the advent and popularity of the liposuction The goal of most abdominoplasty procedures is not only to improve the contour and shape of the abdomen, but to procedure and with a better understanding of skin achieve a smooth, flowing, harmonious contour by improving retraction post-liposuction surgery, many of the the overall silhouette and appearance of the region. The waist previously abdominoplasty procedures are now is an area of paramount importance for the feminine figure, treated by the less invasive and more rapid recovery which begins at the level of the lower ribs and ends at the procedure of liposuction surgery. Nevertheless, level of the iliac crest; its narrowest point is approximately 4cm above the navel. The purpose of this study was to report abdominoplasty still holds a very intricate and self- our results on 30 patients who underwent abdominoplasty satisfying place in the world of cosmetic surgery and improvement of the waistline utilizing Scarpa’s fascial [2] . The goal of most abdominoplasty procedures advancement flaps and plication in the midline. is not only to improve the contour and shape of the abdomen, but to achieve a smooth, flowing, Patients and Technique: During a 13-month period from January 2009 to February 2010 we operated on 30 patients. -

Indications and Treatment of Myofascial Pain

2/25/2017 Indications and Treatment of Myofascial Pain Lisa DeStefano, DO Associate Professor and Chair Department of Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine College of Osteopathic Medicine Michigan State University Common Myofascial Pain Syndromes 1 2/25/2017 2 2/25/2017 Greater Occipital Nerve Impingement Sites . 1: Origin of the third occipital nerve and proximal connection with the greater occipital nerve. 2: Greater occipital nerve as it courses inferior to the inferior oblique muscle. 3: Greater occipital nerve coursing through the semispinalis capitis muscle. 4: Greater occipital nerve exiting the aponeurosis of the trapezius muscle. 5: Greater occipital nerve traveling with the occipital artery. 6: Origin of the greater occipital nerve and relationship to the descending branch of the occipital artery. 7: Suboccipital nerve relation to the vertebral artery and the descending branch of the occipital artery and this nerves interconnection to the greater occipital nerve. 8: Relationship between the third occipital nerve and the C2‐C3 joint complex. Common Treatment Approaches • MFR • MET • Soft Tissue Release • Counterstain • HVLA Etiology of Head and Neck Myofascial Pain Syndromes • Overuse • Posture –Head over the pelvis • Posture – Scapular function • Occlusion –how the teeth control for the proper placement of the mandibular condyle. 3 2/25/2017 Stabilization of the torsobegins with spinotransverse muscle transmission of force onto the epaxial fascia or vertebral aponeurosis. 4 2/25/2017 This then transmits tension into the serratus posterior superior and inferior, which then lifts the upper four ribs and sternum and lowers the lower ribs respectively. In response a force‐ couple is generated between the serratus posterior inferior fascia, external oblique fascia, and the rectus sheath. -

Skeletal System? Skeletal System Chapters 6 & 7 Skeletal System = Bones, Joints, Cartilages, Ligaments

Warm-Up Activity • Fill in the names of the bones in the skeleton diagram. Warm-Up 1. What are the 4 types of bones? Give an example of each. 2. Give 3 ways you can tell a female skeleton from a male skeleton. 3. What hormones are involved in the skeletal system? Skeletal System Chapters 6 & 7 Skeletal System = bones, joints, cartilages, ligaments • Axial skeleton: long axis (skull, vertebral column, rib cage) • Appendicular skeleton: limbs and girdles Appendicular Axial Skeleton Skeleton • Cranium (skull) • Clavicle (collarbone) • Mandible (jaw) • Scapula (shoulder blade) • Vertebral column (spine) • Coxal (pelvic girdle) ▫ Cervical vertebrae • Humerus (arm) ▫ Thoracic vertebrae • Radius, ulna (forearm) ▫ Lumbar vertebrae • Carpals (wrist) • Metacarpals (hand) ▫ Sacrum • Phalanges (fingers, toes) ▫ Coccyx • Femur (thigh) • Sternum (breastbone) • Tibia, fibula (leg) • Ribs • Tarsal, metatarsals (foot) • Calcaneus (heel) • Patella (knee) Functions of the Bones • Support body and cradle soft organs • Protect vital organs • Movement: muscles move bones • Storage of minerals (calcium, phosphorus) & growth factors • Blood cell formation in bone marrow • Triglyceride (fat) storage Classification of Bones 1. Long bones ▫ Longer than they are wide (eg. femur, metacarpels) 2. Short bones ▫ Cube-shaped bones (eg. wrist and ankle) ▫ Sesamoid bones (within tendons – eg. patella) 3. Flat bones ▫ Thin, flat, slightly curved (eg. sternum, skull) 4. Irregular bones ▫ Complicated shapes (eg. vertebrae, hips) Figure 6.2 • Adult = 206 bones • Types of bone -

Posture Alignment and the Surrounding Musculature An

Posture Alignment and the Surrounding Musculature An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Brittany Moffett Thesis Advisor Mary Winfrey-Kovell Ball State University Muncie, Indiana November 2019 Expected Date of Graduation December 2019 Abstract It is reported that musculoskeletal conditions are the most common reason to seek medical consultations in the U.S., therefore, it is important to find the underlying cause of the pain and discomfort that society is experiencing (Osar, 2012). When examining the musculoskeletal system and how it is interconnected with the nervous system, it can be found that society as a whole experiences dysfunction from simple everyday movement patterns that can lead to injury and pain (Page, 2014). One’s posture is critical to health and wellness, and activities of daily living as the core and the spine are crucial in determining how the rest of the body moves and functions. The position of the spine is determined by the neuromuscular system surrounding the spine and along the kinetic chain which affects an individual’s movement patterns. Evidence indicates any small deviation along the kinetic chain will result in change to the neuromuscular system and the increased risk of injury or pain. Because posture and the risk of injury or pain are correlated, it is critical to be able to differentiate between good posture and the different types of posture deviations. The purpose of this paper is to define good posture and provide an understanding of the underlying causes of postural deviations. An analysis of the four types of postural deviations – lordosis, kyphosis, flat back, and sway back will provide the ability to recognize the common types of postural deviations and provide a structured approach to correcting each type of postural deviation. -

Trans-Obturator Cable Fixation of Open Book Pelvic Injuries

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Trans‑obturator cable fxation of open book pelvic injuries Martin C. Jordan 1*, Veronika Jäckle1, Sebastian Scheidt2, Fabian Gilbert3, Stefanie Hölscher‑Doht1, Süleyman Ergün4, Rainer H. Mefert1 & Timo M. Heintel1 Operative treatment of ruptured pubic symphysis by plating is often accompanied by complications. Trans‑obturator cable fxation might be a more reliable technique; however, have not yet been tested for stabilization of ruptured pubic symphysis. This study compares symphyseal trans‑obturator cable fxation versus plating through biomechanical testing and evaluates safety in a cadaver experiment. APC type II injuries were generated in synthetic pelvic models and subsequently separated into three diferent groups. The anterior pelvic ring was fxed using a four‑hole steel plate in Group A, a stainless steel cable in Group B, and a titan band in Group C. Biomechanical testing was conducted by a single‑ leg‑stance model using a material testing machine under physiological load levels. A cadaver study was carried out to analyze the trans‑obturator surgical approach. Peak‑to‑peak displacement, total displacement, plastic deformation and stifness revealed a tendency for higher stability for trans‑ obturator cable/band fxation but no statistical diference to plating was detected. The cadaver study revealed a safe zone for cable passage with sufcient distance to the obturator canal. Trans‑ obturator cable fxation has the potential to become an alternative for symphyseal fxation with less complications. Disruption of the pubic symphysis is commonly seen in pelvic ring injuries of trauma patients 1,2. Te disrup- tion of the anterior pelvic ring might occur in combination with a posterior pelvic ring impairment of variable severity. -

A Device to Measure Tensile Forces in the Deep Fascia of the Human Abdominal Wall

A Device to Measure Tensile Forces in the Deep Fascia of the Human Abdominal Wall Sponsored by Dr. Raymond Dunn of the University of Massachusetts Medical School A Major Qualifying Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Olivia Doane _______________________ Claudia Lee _______________________ Meredith Saucier _______________________ April 18, 2013 Advisor: Professor Kristen Billiar _______________________ Co-Advisor: Dr. Raymond Dunn _______________________ Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................. iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi Authorship Page ............................................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... viii Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review ......................................................................................................... -

A Literature Review How the Stability of the Pelvic Floor Complex Affects the Lumbar Spine By: Abigail Scheer Faculty Advisor: D

A Literature Review How the Stability of the Pelvic Floor Complex Affects the Lumbar Spine By: Abigail Scheer Faculty Advisor: Dr. Brett Winchester 18 October 2013 ABSTRACT This literature review explores the connection between the pelvic floor muscle complex and the stability of the lumbo-pelvic region of the spine. The research analyzed depicts the role of the pelvic floor musculature in the function ability of a person’s core, and how acute low back pain can be diminished and controlled, with a reduction in the likelihood of recurring episodes, if proper stabilization exercises and rehabilitation training are instituted. Weakness of the pelvic floor can result from a myriad of triggers, which can be addressed by studying the operation tactics of a person’s underlying muscle groups, and finding the correct method of improving them. Key Words: pelvic floor muscles, PFM, low back pain, lumbo-pelvic instability, core stability, incontinence Scheer, A. Page 2 INTRODUCTION Pain centered on the lower back is a common phenomenon in the world. It is a condition that appears episodically and with no definite solution in sight. Eventually those thwarted with this ailment surrender to the pain and inconvenience, feeling that even if they win the battle of one flair-up, another incident is just around the corner. Low back pain has become a frequent and costly diagnosis that plagues roughly 38% of the population at some point during a lifetime. It is one of the top injuries to cause professional athletes to be benched during a match. As much as 30% of the professional athletic population has reported holding onto a low back complaint for multiple years.1 This complaint has become so engrained in the norm of everyday culture that a common turn of phrase when a situation goes awry or a person commits an unforgivable faux pas is to relate it to a “pain in the butt (or lumbo-pelvic region).” While low back pain is such a common diagnosis to be gifted, it is also one of the most mysterious when it comes to solving the case as to what the root cause is. -

Glossary of Basic Orthotic & Prosthetic Terminology

Glossary Abduction Moving away from midline. Abductor Muscle involved in active abduction. Acetabulum Socket in pelvis, which receives head of femur. Achilles Tendon Prominent cord at posterior aspect of ankle. Adduction Move toward midline. The position of the components of a prosthesis or orthosis in space Alignment relative to each other and to the patient. Reference position of the body permitting description of location and movements. The individual is standing erect. Head facing forward. Arms Anatomic Position Parallel to the trunk, straight at the sides. Forearms and hands positioned so the palms face forward. Legs straight. Feet parallel to each other. Anterior Toward the front. Not symmetrical; denoting a lack of symmetry between two or more like Asymmetrical parts. The degeneration, or shrinking of a muscle due to lack of use, such as Atrophy in an amputation. Axis Imaginary line passing through center of joint; pivot point. Assembly and alignment of the components of a prosthesis or orthosis Bench alignment using only previously acquired data regarding the patient. Two sides; used to describe an amputee missing both left and right Bilateral extremities. A shell composed of two separate parts that open and shut; used to Bi-valve describe many braces that have two halves; clamshell. Light bulb shaped; circumference small on one end growing larger at Bulbous the bulbous end. CG Center of Gravity. Calcaneus Heel bone Calcification Building up of calcium deposits; bone. Callus Thickening of skin. Carpal The wrist bones and their associated soft parts. Process of modifying the positive model obtained by filling an Cast modification impression in order to obtain a shape which specifies the whole, or part, of the form of the final prosthesis or orthosis.