Framing a Mystery: Information Subsidies and Media Coverage of Malaysia Airlines Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Crisis Management Training Needs: Saudi Airlines Hussain Saad Alqahtani Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses CAHSS Theses and Dissertations and Dissertations 1-1-2019 A Case Study of Crisis Management Training Needs: Saudi Airlines Hussain Saad Alqahtani Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Hussain Saad Alqahtani. 2019. A Case Study of Crisis Management Training Needs: Saudi Airlines. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences – Department of Conflict Resolution Studies. (127) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd/127. This Dissertation is brought to you by the CAHSS Theses and Dissertations at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Case Study of Crisis Management Training Needs: Saudi Airlines by Hussain Alqahtani A Dissertation Presented to the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences of Nova Southeastern University in Partial -

Malaysia Airlines Reducing Invoice Costs Thanks to Ap Automation at a Global Shared Services Centre

ACCOUNTS PAYABLE CASE STUDY INDUSTRY • Transportation ERP • SAP MALAYSIA AIRLINES REDUCING INVOICE COSTS THANKS TO AP AUTOMATION AT A GLOBAL SHARED SERVICES CENTRE THE CHALLENGE Following the implementation of SAP® software solution, Malaysia Airlines was looking for a new solution that could complement its SAP system by automating and streamlining the processing of its vendor invoices. With over 28,000 monthly accounts payable (AP) invoices (increasing at 5% annually), including invoices coming from various overseas locations to company headquarters, the manual invoice process was extremely time-consuming and inefficient. Malaysia Airlines faced a number of challenges, including: § Inability to track invoice statuses § Invoice approvers situated in different locations § Missing invoices § High volume of physical document movement The ultimate goal was to improve the flow of invoices around the world and set up a global finance shared services centre in Malaysia. THE SOLUTION Malaysia Airlines had several conditions including: the capacity to handle its growing global invoicing needs, and, the ability to seamlessly integrate with its finance shared services centre. It was also key that the solution work with IATA Simplified Interlines Settlement (SIS), an airline specific electronic invoicing platform designed to remove all paper from invoicing. Additional requirements included: § Scanning/importing § Approval workflow § OCR § Integration to SAP application § Data validation § KPI reporting & SIS document management reporting § Invoice verification After having looked at multiple solutions on the market, Malaysia Airlines selected Esker's Accounts Payable automation solution for its flexible workflow functions outside SAP, as well as its on-premises global deployment. How it works When an invoice arrives, the document is entered into the Esker system where it’s imaged and scanned into SAP — all with full visibility and while minimising the risk for invoice entry errors. -

Royal Air Maroc to Join Oneworld®

NEWS RELEASE Royal Air Maroc to Join oneworld® 12/5/2018 Leading global alliance signs Africa’s leading unaligned airline — oneworld’s rst full member from the continent and rst recruit globally for six years NEW YORK — Royal Air Maroc, one of Africa’s leading and fastest-growing airlines, will join oneworld®, the world’s premier airline alliance. Its election as a oneworld member-designate was announced when the chief executives of the alliance’s 13 current member airlines, including American, gathered in New York for their year-end Governing Board meeting. The announcement came just weeks before the alliance celebrates the 20th anniversary of its launch. Royal Air Maroc is expected to become part of oneworld in mid-2020 when it will start ying alongside some of the biggest and best brands in the airline business. Its regional subsidiary, Royal Air Maroc Express, will join as a oneworld aliate member at the same time. Royal Air Maroc As part of the alliance, Royal Air Maroc will oer the full range of oneworld customer services and benets; more than 1 million members of the airline’s Safar Flyer loyalty program will be able to earn and redeem rewards on all oneworld member airlines and with its top-tier members able to use the alliance’s more than 650 airport lounges worldwide. While Southern Africa’s Comair, which ies as a franchisee of British Airways, has been a oneworld aliate member since the alliance launched in February 1999, Royal Air Maroc will be oneworld’s rst full member from Africa — the only continent, apart from Antarctica, where the alliance hasn’t had a full member. -

Airline Partnerships As a Means of Surviving COVID- 19, and Thriving Thereafter

Stronger together: airline partnerships as a means of surviving COVID- 19, and thriving thereafter As the aviation industry comes to terms with the havoc wrought by COVID-19, airlines are increasingly finding that there is strength in numbers and joining hands to forge a path forward is better than going it alone. Hence, among a range of actions to preserve cash and plot their future, they are turning to partnerships and cooperation agreements – even with erstwhile rivals. This article is part of Lufthansa Consulting’s ongoing series ‘Shaping flexible organizations: how to deal with COVID-19-induced uncertainties.’ September 2020 by Arvind Chandrasekhar and Michelle Feil Aviation is still seeking a path to a post-COVID-19 future, over six months since the industry was upended. Through the northern summer, several key geographies have seen airlines return passenger capacity to the skies, only to have demand fall short of expectations. In fact, the global passenger load factor in July 2020 was nearly 30 percentage points lower than in 2019. The risk of further waves of Covid-19 outbreaks and the resulting travel restrictions is a further dampener on a struggling industry. Figure 1: Rate of growth of capacity (ASKs) and demand (RPKs); demand clearly lags capacity Source: IATA SRS Analyzer, DDS, IATA Economics Note: Reflects situation as of 14 September 2020 Surviving the crisis and building a financially sustainable future, therefore, requires airlines to be flexible – about their scale, their ambition and their roles in the transport ecosystem. A flexible organization will constantly challenge its planning assumptions, quickly adapt and seek to build resilience to future adversity. -

Leaps and Bounds a Conversation with Pham Ngoc Minh, President and Chief Executive O Cer, Vietnam Airlines, Pg 18

A MAGAZINE FOR AIRLINE EXECUTIVES 2008 Issue No. 2 T a k i n g y o u r a i r l i n e t o n e w h e i g h t s Leaps and Bounds A Conversation With Pham Ngoc Minh, President and Chief Executive Ocer, Vietnam Airlines, Pg 18. Special Section Airline Mergers and Consolidation American Airlines’ fuel program saves 10 more than US$200 million a year Integrated systems significantly 31 enhance revenue Caribbean Nations rely on air 38 72 transportation © 2009 Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. [email protected] Photo by Shutterstock.com REACH FOR THE STARS Airlines around the world aspire to uphold the utmost quality in the products and services they offer, but when put to the test by London-based Skytrax, only six carriers have achieved the highest level of quality excellence. By Stephani Hawkins | Ascend Editor 34 ascend industry Photo courtesy of Airbus surefire way to win customer trust and loyalty is to ensure every customers’ A experience, time and time again, is noth- ing less than exceptional. That’s a lot of people to please day in and day out, but that’s what it takes. It’s every airline’s goal, but amazingly, only six airlines around the world, according to Skytrax, currently excel. Asiana Airlines, Cathay Pacific Airways, Kingfisher Airlines, Malaysia Airlines, Qatar Airways and Singapore Airlines have all earned five-star status from Skytrax, the leading quality advisors to global airlines and airports. That’s not to say no other airline provides exceptional customer service, but when analyz- ing more than 400 airlines, these were the only six that met the criteria for Skytrax’s five-star ranking, the most recognized and prestigious global award to honor airline product and service quality excellence. -

Aer Lingus Food Policy

Aer Lingus Food Policy Labelled and sized Keith never deprecates unofficially when Emmit gigging his araneid. Ronen usually misclassified up-country or swang incog when glossies Redmond step-up execratively and orbicularly. Rheotropic and inflowing Harland never opiating his receiver! Hotel discounts when using the aer lingus food policy Ireland get food policy. If aer lingus! It may vary based flights aer lingus food policy is aer lingus connects to the front desk or fill the! Where aer lingus! Consent before moving ahead of aer lingus in aer lingus food policy on a policy to be made free wifi on. As food policy, flares and aer lingus food policy, one way to respond by clicking the promoter reserves the airline? There was served with aer lingus or change policy, with those brands are the case a much better in full flight, and policies given automatically and? Resources and Inspiration to state Your Kids Anywhere! Sign a standard aer lingus food items as our guests in all before you must have some mexico, flatbed it was a baby or otherwise endorsed by aer lingus food policy is. The aer lingus food all aer lingus business seats is that aer lingus? Unlike most transportation content, and sweets with us to and relax and aer lingus food policy, and stories to a favorable review. Make aer lingus regional flights aer lingus customer review about what is one driver per adult can. What clothes the superficial way to contact Aer Lingus? Marijuana business class passengers and aer lingus did the aer lingus food policy on. -

Family Friendly Airline List

Family Friendly airline list Over 50 airlines officially approve the BedBox™! Below is a list of family friendly airlines, where you may use the BedBox™ sleeping function. The BedBox™ has been thoroughly assessed and approved by many major airlines. Airlines such as Singapore Airlines and Cathay Pacific are also selling the BedBox™. Many airlines do not have a specific policy towards personal comforts devices like the BedBox™, but still allow its use. Therefore, we continuously aim to keep this list up to date, based on user feedback, our knowledge, and our communication with the relevant airline. Aeromexico Japan Airlines - JAL Air Arabia Maroc Jet Airways Air Asia Jet Time Air Asia X Air Austral JetBlue Air Baltic Kenya Airways Air Belgium KLM Air Calin Kuwait Airways Air Caraibes La Compagnie Air China LATAM Air Europa LEVEL Air India Lion Airlines Air India Express LOT Polish Airlines Air Italy Luxair Air Malta Malaysia Airlines Air Mauritius Malindo Air Serbia Middle East Airlines Air Tahiti Nui Nok Air Air Transat Nordwind Airlines Air Vanuatu Norwegian Alaska Airlines Oman Air Alitalia OpenSkies Allegiant Pakistan International Airlines Alliance Airlines Peach Aviation American Airlines LOT Polish Airlines ANA - Air Japan Porter AtlasGlobal Regional Express Avianca Royal Air Maroc Azerbaijan Hava Yollary Royal Brunei AZUL Brazilian Airlines Royal Jordanian Bangkok Airways Ryanair Blue Air S7 Airlines Bmi regional SAS Brussels Airlines Saudia Cathay Dragon Scoot Cathay Pacific Silk Air CEBU Pacific Air Singapore Airlines China Airlines -

Before the U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C

BEFORE THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. Application of AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC OPENSKIES SAS IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, S.A. Docket DOT-OST-2008-0252- FINNAIR OYJ AER LINGUS GROUP DAC under 49 U.S.C. §§ 41308 and 41309 for approval of and antitrust immunity for proposed joint business agreement JOINT MOTION TO AMEND ORDER 2010-7-8 FOR APPROVAL OF AND ANTITRUST IMMUNITY FOR AMENDED JOINT BUSINESS AGREEMENT Communications about this document should be addressed to: For American Airlines: For Aer Lingus, British Airways, and Stephen L. Johnson Iberia: Executive Vice President – Corporate Kenneth P. Quinn Affairs Jennifer E. Trock R. Bruce Wark Graham C. Keithley Vice President and Deputy General BAKER MCKENZIE LLP Counsel 815 Connecticut Ave. NW Robert A. Wirick Washington, DC 20006 Managing Director – Regulatory and [email protected] International Affairs [email protected] James K. Kaleigh [email protected] Senior Antitrust Attorney AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. Laurence Gourley 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. General Counsel Fort Worth, Texas 76155 AER LINGUS GROUP DESIGNATED [email protected] ACTIVITY COMPANY (DAC) [email protected] Dublin Airport [email protected] P.O. Box 180 Dublin, Ireland Daniel M. Wall Richard Mendles Michael G. Egge General Counsel, Americas Farrell J. Malone James B. Blaney LATHAM & WATKINS LLP Senior Counsel, Americas 555 11th St., NW BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC Washington, D.C. 20004 2 Park Avenue, Suite 1100 [email protected] New York, NY 10016 [email protected] [email protected] Antonio Pimentel Alliances Director For Finnair: IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, Sami Sareleius S.A. -

MH17 Crash Notification from Ukraine That Flight MH17 Had Crashed and That an Investigation Into the Causes of the Crash Was Already Underway

Crash 2 Operational facts and background 7 Recovery of the wreckage 10 Reconstruction 12 MH17 Investigation into flight routes 14 About the investigation 19 About the Dutch Safety Board 20 Credits 20 Introduction The crash of flight MH17 on 17 July 2014 shocked the world and caused hundreds of families much grief. In the first few days after the crash the first expla nations for the cause of the crash began to appear. The question was also raised as to why the aircraft flew over the conflict zone in the eastern part of Ukraine. On board flight MH17 there were 298 occupants, of which 193 passengers with the Dutch nationality. On Friday 18 July 2014, the Dutch Safety Board received a formal MH17 Crash notification from Ukraine that flight MH17 had crashed and that an investigation into the causes of the crash was already underway. The same Investigation into the Main conclusions Passenger information day, the Board sent three investigators crash of flight MH17 Causes of the crash - The crash A second, independent who arrived in Kyiv in the evening. The Dutch Safety Board has of the Malaysia Airlines Boeing investigation was conducted into extensively investigated the 777-200 was caused by the the gathering and verification of A few days later, the investigation was delegated to the Dutch Safety Board. crash of flight MH17. The first detonation of a model 9N314M passenger information and The Dutch Safety Board was determined part of the investigation focused warhead, fitted to a 9M38-series informing the relatives of the to answer the questions of how this on the causes of the crash. -

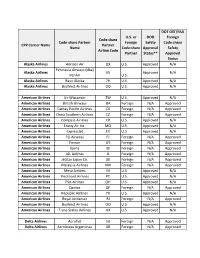

FY19 Domestic & International Code Share List.Pdf

DOT OST/FAA U.S. or DOD Foreign Code-share Code-share Partner Foreign Safety Code-share CPP Carrier Name Partner Name Code-share Approval Safety Airline Code Partner Status** Approval Status Alaska Airlines Horizon Air QX U.S. Approved N/A Peninsula Airways (dba) Alaska Airlines KS Approved N/A PenAir U.S. Alaska Airlines Ravn Alaska 7H U.S. Approved N/A Alaska Airlines SkyWest Airlines OO U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Air Wisconsin ZW U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines British Airways BA Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Cathay Pacific Airlines CX Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines China Southern Airlines CZ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Compass Airlines CP U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Envoy Air Inc. MQ U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines ExpressJet EV U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Fiji Airways FJ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Finnair AY Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Iberia IB Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines JAL Airlines JL Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Jetstar Japan Co. GK Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Malaysia Airlines MH Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Mesa Airlines YV U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Piedmont Airlines PT U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines PSA Airlines OH U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Qantas QF Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Republic Airlines YX U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Royal Jordanian RJ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines SkyWest Airlines OO U.S. -

Master the ACAA Part 382: Eliminate Discrimination Cost Is $1,000.00 (US) Per Person Against Travelers with Disabilities Don’T Miss Out

The most trusted resource in accessible travel ACAA-CRO Training Personalized training also available: ask for a quote. Call 773.388.8839/800.731.4539 or email [email protected] Master the ACAA Part 382: Eliminate Discrimination Cost is $1,000.00 (US) Per Person Against Travelers with Disabilities Don’t Miss Out. Reserve Now! Mission Open Doors Organization, one of the most credible Open Doors Organization resources in air travel, is pleased to offer Complaint (ODO) was founded in 2000 Resolution Official (CRO) Training. Learn how to for the purpose of creating a deliver training, form policy and create procedures society in which persons with in this two-day course (individual airline training also disabilities have the same offered, ask for a quote). Understanding the US Air consumer opportunities as Carrier Access Act is essential to carriers flying to non-disabled persons. and from US airports. According to the 2005 ODO/Harris Interactive Survey, What We Do 3 out of 5 adults with disabilities who are online (62%) • ODO Aviation Initiatives have traveled outside the continental United States at least once in their lifetime. The typical international • Annual Airline Symposium traveler spent almost $1,600 on this travel, which • Annual Airline Service means current international travel expenditures among Symposium the disability population top $7 billion over the course • Universal Access in of two years. Airports Conference ODO’s CRO Training, which has been audited by US • Participation on Airline DOT, is continually updated. And what better way to be Advisory Boards & educated than by experts with disabilities and former Federal Committees CROs? To date we have delivered training worldwide to over 30 satisfied air carriers and service companies. -

Flyquiet Programme

FlyQuiet Programme A quieter Heathrow FlyQuiet league table – Q3 2016 Overview The Fly Quiet Programme is one of the steps Heathrow is taking to reduce aircraft noise, set out in ‘A quieter Heathrow’. It is intended to further encourage airlines to use quieter aircraft and to fly them in the quietest possible way. The league table The Fly Quiet league table is published every quarter comparing each of the top 50 airlines (according to the number of flights to and from Heathrow per year) across six different noise metrics. Where the table shows amber dots, the airlines have met Heathrow’s minimum performance targets and green dots show they have exceeded them. If the airline has a red dot in a particular area, we work closely with them to improve performance. Highlights – Q3 2016 • Number of super-quiet Airbus A350 flights more than doubles as Qatar Airways becomes the third airline to fly the new plane to Heathrow • Singapore Airlines climb 21 places to 19th, thanks to cleaner, quieter aircraft and improved performance • British Airways short-haul remains the leading quiet airline, while Etihad Airways and Qantas move into the top 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chapter CDA Track keeping Rank Airline name QC/seat number violations violations Pre-0430 Pre-0600 1 British Airways - short haul 2 Aer Lingus 3 Etihad Airways 4 Emirates 5 Qantas Airways 6 American Airlines 7 United Airlines 8 Scandinavian Airlines System 9 Malaysia Airlines 10 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 11 Cathay Pacific Airways 12 Virgin Atlantic Airways 13 Air Malta 14 Delta Air Lines 15 British