Gaming the System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J

University of Massachusetts School of Law Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts School of Law Faculty Publications 2016 The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J. Peltz-Steele University of Massachusetts School of Law - Dartmouth, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard J. Peltz-Steele, The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between (Sept 27, 2016) (unpublished paper). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard Peltz-Steele Abstract With Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 on the horizon, the process for selecting hosts for the World Cup of men’s football has been plagued by charges of corruption and human rights abuses. FIFA celebrated key developing economies with South Africa 2010 and Brazil 2014. But amid the aftermath of the global financial crisis, those sitings surfaced grave and persistent criticism of the social and economic efficacy of sporting mega-events. Meanwhile new norms emerged in global governance, embodied in instruments such as the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the Sustainable Development Goals. These norms posit that commercial aims can be harmonized with socioeconomic good. FIFA seized on the chance to restore public confidence and recommit itself to human exultation in sport, adopting sustainability strategies and engaging the architect of the UNGP to develop a human rights policy. -

Protecting Children in Virtual Worlds Without Undermining Their Economic, Educational, and Social Benefits

Protecting Children in Virtual Worlds Without Undermining Their Economic, Educational, and Social Benefits Robert Bloomfield* Benjamin Duranske** Abstract Advances in virtual world technology pose risks for the safety and welfare of children. Those advances also alter the interpretations of key terms in applicable laws. For example, in the Miller test for obscenity, virtual worlds constitute places, rather than "works," and may even constitute local communities from which standards are drawn. Additionally, technological advances promise to make virtual worlds places of such significant social benefit that regulators must take care to protect them, even as they protect children who engage with them. Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................ 1177 II. Developing Features of Virtual Worlds ...................................... 1178 A. Realism in Physical and Visual Modeling. .......................... 1179 B. User-Generated Content ...................................................... 1180 C. Social Interaction ................................................................. 1180 D. Environmental Integration ................................................... 1181 E. Physical Integration ............................................................. 1182 F. Economic Integration ........................................................... 1183 * Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University. This Article had its roots in Robert Bloomfield’s presentation at -

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 1 / 3 Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 2 / 3 Fifa 20 PC Download, Full Version, Demo, Gratuit, Telecharger, 17,18,19,16,15 demo. Fifa 20 Download PC, Gratuit, Full Version, Crack, Telecharger. ... FIFA '99, FIFA 2000, FIFA 2001, FIFA 2002, FIFA Football 2003, FIFA Football 2004, FIFA .... FIFA 19 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from CPY, STEAMPUNKS, RELOADED, etc. and sends you an email and phone notification when the games you follow get cracked! ... Lord of the n00bs (15) ..... ted2001. Apprentice (63). military-rank profile. 2. NOPE I WOULD .... Tải game FIFA 2001 (2000) full crack miễn phí - RipLinkNerverDie.. FIFA 2001 (known as FIFA 2001: Major League Soccer in North America) is a 2001 FIFA video game and the sequel to FIFA 2000 and was succeeded by FIFA .... Download FIFA 2001 Demo. This is the ... Serial Link. Null Modem ... FIFA 15. Soccer simulation game for Windows and other platforms. Cue Club thumbnail .... FIFA 15 (Video Pc Game) Highly Compressed Free Download Setup RIP ... List Free Download PC Full Highly Download All FIFA Games including FIFA 2001 2002 ... FIFA 2005 Football PC Game Download From Torrent Soccer Online Free!. Hi this is a realistic !!!!! patch that makes the players and teams that bit more ...... ENGLISH Brazilian adboards (JH Cup) for Fifa 2001 Download size: 15,7KB .... FIFA 20 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from ... i hope they will give us a cracked fifa 20 as gift for Christmas this will be a very big big prize for alot of people .. -

Ski Nautique 200 - Closed Bow Ski Nautique 200 - Open Bow

2018 OWNERS MANUAL SKI NAUTIQUE 200 - CLOSED BOW SKI NAUTIQUE 200 - OPEN BOW Ski_Sport_200_front matter_2018.qxp_Nautique Ski front matter.qxd 7/13/17 2:52 PM Page i Dear Nautique Owner, Welcome to the Nautique Family! For over 90 years, Nautique has been dedicated to providing our customers and their families with the finest inboard boats available. It’s our passion to create the best performing boats in the industry. Boats that allow you to escape the routine of everyday life. Our customers don’t just own a Nautique, they live the Nautique life. Your boat has been built with the best material and workmanship available, a legacy handed down from our founder. Our wealth of experience gives us the edge in innovation, quality and performance. We have the most dedicated and loyal employees in the industry. Hands down. Every day, our employees do more than just punch a clock; they take personal pride in every boat that comes down the line. Review this Owner’s Manual for your boat. We have assembled this manual to inform you about your Nautique and educate you further on boating. Please pay particular attention to the safety statements labeled as DANGER, WARNING, CAUTION and NOTICE. These statements alert you to possible safety hazards to avoid so you can have a safer boating experience. There are also many tips and tricks on care and maintenance sprinkled throughout the manual. Boating is very important to us and we would like you to enjoy many years of boating in your Nautique. By purchasing a Nautique, you have taken the first step in trading your old lifestyle for a new one. -

HIAS Report Template

Roadmap to Recovery A Path Forward after the Remain in Mexico Program March 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 The Stories of MPP .................................................................................................. 1 Our Work on the Border ......................................................................................... 2 Part One: Changes and Challenges at the Southern Border ................................. 4 Immigration Under the Trump Administration ...................................................... 5 How MPP Worked ................................................................................................... 9 Situation on the Ground ......................................................................................... 12 Nonrefoulement Interviews .................................................................................... 18 Effects on the Legal Cases ....................................................................................... 19 Lack of Access to Legal Counsel .............................................................................. 20 The Coronavirus Pandemic and Title 42 ................................................................. 20 Part Two: Recommendations ................................................................................ 22 Processing Asylum Seekers at Ports of Entry .......................................................... 23 Processing -

Exklusivpremiere Von FIFA 20, Zocken Mit Esport-Profis, Live-Auftritte Von

MediaMarkt mit Highlight-Programm auf der gamescom 2019 Exklusivpremiere von FIFA 20, Zocken mit eSport- Profis, Live-Auftritte von Dame und Jan Hegenberg Ingolstadt, 30.07.2019: Ende August schlagen Zocker-Herzen wieder höher: Die gamescom lädt zur weltweit größten Messe für Videospiele nach Köln. Auch in diesem Jahr ist MediaMarkt mit seinem Gaming- Portal GameZ.de als Aussteller vertreten. In Halle 10.1 erwartet die Besucher vom 20. bis 24. August 2019 eine einzigartige Gaming- Atmosphäre. Am rund 1.000 Quadratmeter großen Stand von MediaMarkt gibt es ein umfangreiches Show-Programm mit Live- Spielen, spannenden Battles, magischen Cosplay-Events sowie die neueste Hardware zum Testen. Die Fans des Gaming-Klassikers FIFA dürfen sich zudem auf eine besondere Gelegenheit freuen: Sie können am Stand die noch unveröffentlichte Version von FIFA 20 anspielen. Am Donnerstagabend kommt außerdem Sänger und Songwriter Dame vorbei und performt live. 1 / 3 Täglich von 10 bis 20 Uhr erleben die Besucher am Stand von MediaMarkt virtuelle Welten und jede Menge Spieleneuheiten. Zu den Höhepunkten zählt dabei unter anderem FIFA 20: Das Release des Spiels ist erst für Ende September 2019 angesetzt; am Stand von MediaMarkt können es Neugierige schon vorab testen und gegeneinander antreten. Auf Tuchfühlung mit eSportlern, Paluten, Dame und Jan Hegenberg Alle eSport-Fans können am Mittwoch (21.08.) und Donnerstag (22.08.) ihre Idole des VfL Wolfsburg und Hertha BSC auf der GameZ.de-Bühne erleben. Die beiden Mannschaften zocken live FIFA 20 und werden unter anderem mit den neuen Headsets „Elite Pro 2“ von Turtle Beach ausgestattet – Expertentipps für alle Besucher natürlich inklusive. -

Insane in the Mens Rea: Why Insanity Defense Reform Is Long Overdue

INSANE IN THE MENS REA: WHY INSANITY DEFENSE REFORM IS LONG OVERDUE Louis KAcHuLIs* ABSTRACT While there have been advances in both the criminal justice system and the mental health community in recent years, the intersection of the two has not seen much progress. This is most apparent when considering the insanity defense. This Note explores the history and public perception of the insanity defense, the defense's shortcomings, and attempts to provide a model for insanity defense reform. I spend the first section of the Note exploring the history of the insanity defense and show where the defense sits today. The Note then examines the public perception of the insanity defense, and the news media's influence on that perception, using two recent events as small case studies. The last section of the Note proposes a new model insanity defense, and a plan to implement it. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................. ..... 246 II. INSANITY DEFENSE - HISTORICAL IMPLICATIONS AND *Class of 2017, University of Southern California Gould School of Law, B.S. Chemical Engineering, North Carolina State University. This Note is dedicated to those in the criminal justice system suffering from mental health issues. While we work as a society to solve the crisis that is mental health, we cannot forget those who are most vulnerable. I would like to thank Professor Elyn Saks for her guidance and direction with this Note, Chris Schnieders of the Saks Institute for his assistance, and lastly, my parents and Brittany Dunton for their overwhelming support. 245 246 REVIEW OF LA WAND SOCIAL JUSTICE [Vol. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Risks of Discrimination Through the Use of Algorithms

Risks of Discrimination through the Use of Algorithms Carsten Orwat Risks of Discrimination through the Use of Algorithms A study compiled with a grant from the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency by Dr Carsten Orwat Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis (ITAS) Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) Table of Contents List of Tables 5 List of Abbreviations 6 Acknowledgement and Funding 7 Summary 8 1. Introduction 10 2. Terms and Basic Developments 11 2.1 Algorithms 11 2.2 Developments in data processing 12 2.2.1 Increasing the amount of data relating to an identifiable person 12 2.2.2 Expansion of algorithm-based analysis methods 13 2.3 Algorithmic and data-based differentiations 16 2.3.1 Types of differentiation 16 2.3.2 Scope of application 18 2.3.3 Automated decision-making 20 3. Discrimination 23 3.1 Terms and understanding 23 3.2 Types of discrimination 25 3.3 Statistical discrimination 25 3.4 Changes in statistical discrimination 27 4. Cases of Unequal Treatment, Discrimination and Evidence 30 4.1 Working life 30 4.2 Real estate market 34 4.3 Trade 35 4.4 Advertising and search engines 36 4.5 Banking industry 38 4 4.6 Medicine 40 4.7 Transport 40 4.8 State social benefits and supervision 41 4.9 Education 44 4.10 Police 45 4.11 Judicial and penal system 47 4.12 General cases of artificial intelligence 49 5. Causes of Risks of Discrimination 53 5.1 Risks in the use of algorithms, models and data sets 53 5.1.1 Risks in the development of algorithms and models 53 5.1.2 Risks in the compilation of data sets and characteristics -

How to Get Minecraft on Chromebook for Free

How To Get Minecraft On Chromebook For Free How To Get Minecraft On Chromebook For Free CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MINECRAFT GENERATOR Best Mods For The Survival Mode When you look at why people might want to use mods over more new content, it's because they like adding new things and making their experience better. These mods improve upon what already exists in Minecraft which is why everyone likes them so much. More Info Download: MINECRAFT MODS", As you can see, the different kinds of mods differ in many ways. Knowing them is important because you will be able to identify each of them when you are browsing for a mod.", Minecraft Bedrock Edition offers a much more convenient way to play Minecraft and it's compatible with iOS, Android and Windows 10 devices. You don't need any special hardware or software in order to use your server. All you need is a mobile device to connect to it and you're ready to go. The process of starting your server is very simple and anyone can do it, so you'll be playing in no time! You can also make purchases with in- game currency for extra characters, skins and other stuff from the Minecraft Marketplace, so if you decide to buy something from there you won't have any problems or issues at all.", "Rust" takes place in a post-apocalyptic world where climate change has reportedly caused most animals (including humans) to become extinct. A player begins their journey by choosing to build themselves a shelter or start mining and gather resources as soon as possible for crafting valuable items which can be sold for money. -

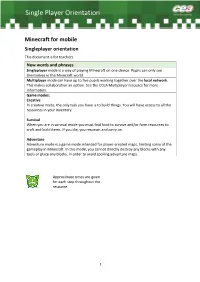

Single Player Orientation

Single Player Orientation Minecraft for mobile Singleplayer orientation This document is for teachers. New words and phrases Singleplayer mode is a way of playing Minecraft on one device. Pupils can only see themselves in the Minecraft world. Multiplayer mode can have up to five pupils working together over the local network. This makes collaboration an option. See the CCEA Multiplayer resource for more information. Game modes: Creative In creative mode, the only task you have is to build things. You will have access to all the resources in your inventory. Survival When you are in survival mode you must find food to survive and/or farm resources to craft and build items. If you die, you respawn and carry on. Adventure Adventure mode is a game mode intended for player-created maps, limiting some of the gameplay in Minecraft. In this mode, you cannot directly destroy any blocks with any tools or place any blocks, in order to avoid spoiling adventure maps. Approximate times are given for each step throughout the resource. 1 Single Player Orientation Learning outcomes When pupils have completed Activity: Singleplayer creative mode they will have: Created an avatar; Created a new world in singleplayer mode, named the world and set the game mode to creative; Explored the world in creative mode, using the inventory and hotbar; Created a small shelter in creative mode; Documented their build by taking a snapshot; and Helped fellow pupils through the steps, where appropriate. When pupils have completed Activity: Singleplayer survival mode they will have: Set the game mode to survival; Explored the world in survival mode; Completed a selection of Recipes in survival mode; Documented their crafting activities by taking a series of snapshots; and Helped fellow pupils through the steps, where appropriate. -

The Minecraft Session Table of Contents

Welcome to the Minecraft session Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….Slides 3-8 Creative Mode……………………………………………………………………………… Slide 9 Survival Mode………………………………………………………………………………. Slide 10-16 Tools…………………………………………………………………………………………………… Slide 12 Difficulties…………………………………………………………………………………………. Slide 13 Monsters……………………………………………………………………………………………..Slides 14 & 15 Weapons & Armor………………………………………………………………………………. Slide 16 Hardcore Mode……………………………………………………………………………. Slide 17 Crafting……………………………………………………………………………………….. Slides 18 & 19 Controls……………………………………………………………………………………….. Slide 20 Today’s Session……………………………………………………………………………. Slide 21 What is Minecraft? Minecraft is an open world sandbox game that focuses on building, exploration, and survival. It is an independently developed (indie) game created by Markus Persson and his company Mojang. Although there is an “ending” to the game, the user sets out his/her own objectives, as each action in the game provides rewards. Background Originally known as Cave Game, the first development phase of Minecraft began on May 10th, 2009. After a short development cycle of only 6 days, the first version of the game was publicly released on the 17th of May, 2009. This phase of the game would later become known as Classic, and it can still be played to this day. Over the next couple of years, Minecraft would go through many updates and changes, before being officially released on November 18th, 2011. The Rise of Minecraft Being an indie game, Minecraft lacked a fan base upon initial release. At the time, YouTube personalities began to upload “Let’s Plays,” videos in which people would play a video game and provide live commentary of their interactions. SeaNanners and YogsCast, two successful YouTube channels (at the time roughly 200,000-400,000 subscribers each) presented their adventures in this unknown game to a large audience which multiplied as the videos were spread on social media.