Mourning with Hope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEBRUARY 2006 Liahonaliahona

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • FEBRUARY 2006 LiahonaLiahona COVER STORY: Young Adults—Temple Blessings Even before You Enter, p. 10 More Than a Temple Marriage, p. 16 The Plan for My Life, p. F4 February 2006 Vol. 30 No. 2 LIAHONA 26982 LIAHONA, FEBRUARY 2006 Official international magazine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints The First Presidency: Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, James E. Faust FOR ADULTS Quorum of the Twelve: Boyd K. Packer, L. Tom Perry, 2 First Presidency Message: Refined in Our Trials Russell M. Nelson, Dallin H. Oaks, M. Russell Ballard, President James E. Faust Joseph B. Wirthlin, Richard G. Scott, Robert D. Hales, Jeffrey R. Holland, Henry B. Eyring, Dieter F. Uchtdorf, 10 Young Adults and the Temple Elder Russell M. Nelson David A. Bednar 20 Confidence to Marry Melissa Howell Editor: Jay E. Jensen Advisers: Monte J. Brough, Gary J. Coleman, 25 Visiting Teaching Message: Building Faith in the Lord Jesus Christ Yoshihiko Kikuchi 30 The Fulness of the Gospel: Life before Birth Managing Director: David L. Frischknecht Editorial Director: Victor D. Cave 39 Lessons from the Old Testament: In the World but Not of the World Senior Editors: Larry Hiller, Richard M. Romney Graphics Director: Allan R. Loyborg Elder Quentin L. Cook Managing Editor: Victor D. Cave 42 Teaching with Church Magazines Don L. Searle Assistant Managing Editor: Jenifer L. Greenwood 44 Latter-day Saint Voices Associate Editors: Ryan Carr, Adam C. Olson Assistant Editor: Susan Barrett Led to a Sandwich Shop Editorial Staff: Shanna Butler, Linda Stahle Cooper, LaRene Porter Gaunt, R. -

Utah Territory. Message of the President of the United States

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 5-2-1860 Utah Territory. Message of the President of the United States, communicating, in compliance with a resolution of the House, copies of correspondence relative to the condition of affairs in the Territory of Utah. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Exec. Doc. No. 78, 36th Cong. 1st Sess. (1860) This House Executive Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 36TH CoNGREss, l HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. S Ex. Doc. Ist Session. S i No. 78. UTAH TERRITORY. MESS.AGE OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, COJIUIUNICATING1 In compliance with a resolutirm of the House, copies of cm·respondence relative to the condition of affairs in the Territory of Utah. MAY 2, 1860.-Laid upon the table and ordered to be printed. To the House of Representatives: In compliance with the resolution of the House of Representatives of l\Iarch 26, 1860, requesting "copies of all official correspondence between the civil and military officers stationed in Utah Territory, with the heads or bureaus of their respective departments) or between any of said officers, illustrating or tending to show the condition of affairs in said Territory since the 1st day of October, 1857, and which may not have been heretofore officially published," I transmit reports from the Secretaries of State and of War, and the documents by which they were accompanied. -

FEBRUARI 2006 Liahonaliahona

ÅRGÅNG 130 • NUMMER 2 • JESU KRISTI KYRKA AV SISTA DAGARS HELIGA • FEBRUARI 2006 LiahonaLiahona FÖRSTASIDESARTIKEL: Unga vuxna — Templets välsignelser också innan du kommer dit, s 10 Mer än ett tempeläktenskap, s 16 Planen för mitt liv, s LS4 Februari 2006 • Årgång 130 • Nummer 2 LIAHONA 26982 180 LIAHONA, FEBRUARI 2006 Officiell tidskrift för Jesu Kristi Kyrka av Sista Dagars Heliga Första presidentskapet: Gordon B Hinckley, Thomas S Monson, James E Faust De tolvs kvorum: Boyd K Packer, L Tom Perry, FÖR VUXNA Russell M Nelson, Dallin H Oaks, M Russell Ballard, Joseph B Wirthlin, Richard G Scott, Robert D Hales, 2 Budskap från första presidentskapet: Förädlade genom våra prövningar Jeffrey R Holland, Henry B Eyring, Dieter F Uchtdorf, David A Bednar James E Faust Chefredaktör: Jay E Jensen 10 Unga vuxna och templet Russell M Nelson Rådgivande: Monte J Brough, Gary J Coleman, Yoshihiko Kikuchi 20 Mod att gifta sig Melissa Howell Verkställande direktör: David L Frischknecht Planerings- och redigeringschef: Victor D Cave 25 Besökslärarnas budskap: Bygg upp din tro på Herren Jesus Kristus Seniorredaktörer: Larry Hiller, Richard M Romney Grafisk chef: Allan R Loyborg 30 Evangeliets fullhet: Livet före födelsen Redaktionschef: Victor D Cave 39 Lärdomar från Gamla testamentet: I världen men inte av världen Biträdande redaktionschef: Jenifer L Greenwood Medredaktörer: Ryan Carr, Adam C Olson Quentin L Cook Biträdande redaktör: Susan Barrett Redaktionspersonal: Shanna Butler, Linda Stahle Cooper, 42 Undervisa med hjälp av kyrkans tidningar Don -

Février 2006 Liahona

ÉGLISE DE JÉSUS-CHRIST DES SAINTS DES DERNIERS JOURS • FÉVRIER 2006 LeLe Liahona Liahona DANS CE NUMÉRO : Jeunes Adultes, les bénédictions du temple avant même d’y entrer, p. 10 Plus qu’un mariage au temple, p. 16 Le plan de ma vie, p. A4 Février 2006 Vol. 7 n° 2 LE LIAHONA 26982-140 LE LIAHONA, FÉVRIER 2006 Publication française officielle de l’Eglise de Jésus-Christ des Saints des Derniers Jours. Première Présidence : Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, James E. Faust POUR LES ADULTES Collège des Douze : Boyd K. Packer, L. Tom Perry, Russell M. Nelson, Dallin H. Oaks, M. Russell Ballard, 2 Message de la Première Présidence : Raffinés par nos épreuves Joseph B. Wirthlin, Richard G. Scott, Robert D. Hales, Jeffrey R. Holland, Henry B. Eyring, Dieter F. Uchtdorf, James E. Faust David A. Bednar Directeur de la publication : Jay E. Jensen 10 Les jeunes adultes et le temple Russell M. Nelson Consultants : Monte J. Brough, Gary J. Coleman, Yoshihiko Kikuchi 20 Ayez confiance dans le mariage Melissa Howell Directeur administratif : David L. Frischknecht 25 Message des instructrices visiteuses : Édifier la foi au Seigneur Directeur de la rédaction : Victor D. Cave Rédacteurs principaux : Larry Hiller, Richard M. Romney Jésus-Christ Directeur du graphisme : Allan R. Loyborg Rédacteur en chef : Victor D. Cave 30 La plénitude de l’Évangile : La vie avant la naissance Rédacteurs en chef adjoints : Jenifer L. Greenwood Rédacteurs associés : Ryan Carr, Adam C. Olson 39 Leçons de l’Ancien Testament : Dans le monde mais pas Rédacteur adjoint : Susan Barrett du monde Quentin L. -

Compte Rendu De La 149E Conférence Annuelle De F Église De Jésus-Christ Des Saints Des Derniers Jours

Compte rendu de la 149e conférence annuelle de F Église de Jésus-Christ des Saints des Derniers Jours Octobre 1979 CXXIX Numéro 10 O M ri ^ b S ’ii fl Publication de Octobre 1979 V, 12 9 l’Eglise de Jesus-Christ des O X X IX Saints des Derniers Jours N um éro 10 Première Présidence: Spencer W. Kimball, N. Eldon Tanner, Marion G. Romney. Conseil des Douze: Ezra Taft Benson, Mark E. Petersen, LeGrand Richards, Howard W. Hunter, Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, Boyd K. Packer, Marvin J. Ashton. Bruce R. McConkie, L. Tom Perry, David B. Haight, James E. Faust. Comité consultatif: M. Russell Ballard, Rex D. Pinegar, Hugh W. Pinnock. Rédacteur en chef: M. Russell Ballard. Rédaction des Magazines internationaux:Larry A. Hiller - rédacteur en chef, Carol D. Larsen - rédactrice en chef adjointe, Roger Gylling - illustrateur. Rédaction de l’Etoile: Christiane Lebon, Service des Traductions, 7 rue Hermel, 75018 PARIS. Rédacteur local: Alain Marie, 33 rue Galilée, F-75116 Paris, Tél. 16 (1) 720 94 95. Compte rendu de la 149e conférence annuelle de l’Eglise de Jésus-Christ des Saints des Derniers Jours Liste alphabétique des orateurs Ashton, Marvin J........................................ 110 Hunter, Howard W....................................... 41 Benson, Ezra T aft............................ 55, 142 K im ball, Spencer W 5, 80, 135, 166 Brown, Victor L.......................................... 149 McConkie, Bruce R ................................... 156 Burton, Théodore M .................................. 119 Monson, Thomas S....................................... 60 Derrick, Royden G..................................... 45 Packer, Boyd K ........................................... 130 Dunn, Loren C............................................ 115 Paramore, James M ...................................... 95 Dunn, Paul H............................................... 12 Perry, L. T o m ................................................. 20 Durham, G. -

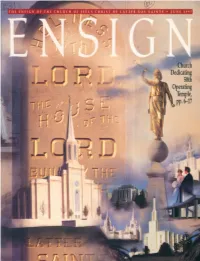

Church Dedicating 50Th Operating Temple, Pp

Church Dedicating 50th Operating Temple, pp. 6-17 THE PIONEER TREK NAUVOO TO WINTER QUARTERS BY WILLIAM G. HARTLEY Latter-day Saints did not leave Nauvoo, Illinois, tn 1846 tn one mass exodus led by President Brigham Young but primarily tn three separate groups-tn winter, spring, and fall. Beginning in February 1846, many Latter-day Saints were found crossing hills and rivers on the trek to Winter Quarters. he Latter-day Saints' epic evacuation from Nauvoo, ORIGINAL PLAN WAS FOR SPRING DEPARTURE Illinois, in 1846 may be better understood by com On 11 October 1845, Brigham Young, President and Tparing it to a three-act play. Act 1, the winter exo senior member of the Church's governing Quorum of dus, was President Brigham Young's well-known Camp Twelve Apostles, responded in behalf of the Brethren to of Israel trek across Iowa from 1 March to 13 June 1846, anti-Mormon rhetoric, arson, and assaults in September. involving perhaps 3,000 Saints. Their journey has been He appointed captains for 25 companies of 100 wagons researched thoroughly and often stands as the story of each and requested each company to build its own the Latter-day Saints' exodus from Nauvoo.1 Act 2, the wagons to roll west in one massive 2,500-wagon cara spring exodus, which history seems to have overlooked, van the next spring.2 Church leaders instructed mem showed three huge waves departing Nauvoo, involving bers outside of Illinois to come to Nauvoo in time to some 10,000 Saints, more than triple the number in the move west in the spring. -

Biography of Mary Anner Armstrong (Thorn) Pioneer of 1853 Written by Her Granddaughter Margaret Johnson Miner

BIOGRAPHY OF MARY ANNER ARMSTRONG (THORN) PIONEER OF 1853 WRITTEN BY HER GRANDDAUGHTER MARGARET JOHNSON MINER BORN, 22 SEPTEMBER 1784, DUTCHESS COUNTY, NEW YORK ARRIVED IN UTAH 9 SEPTEMBER 1853 COMPANY OF CAPTAIN DANIEL C. MILLER AND JOHN W. COOLEY MARRIED RICHARD THORN, 6 SEPTEMBER 1806, CLINTON, DUTCHESS COUNTY, NEW YORK DIED 7 MARCH 1856, SALT LAKE CTTY, UTAH WRITTEN BY GRAND DAUGHTER MARGARET JOHNSON MINER IN 1972 SUBMITTED 7 APRIL 1972 BY MARGARET J. MINER, EAST SOUTH UTAH COUNTY DAUGHTERS OF UTAH PIONEERS CAMP AARON JOHNSON, SPRINGVILLE, UTAH May B. Isaacson, Co. Historian MARY ANNER ARMSTRONG THORN, PIONEER OF 1855 Mary Anner Armstrong was born in Dutchess Co., New York Sept. 22, 1784. She was married to Richard Thorn Sept. 6, 1806 in Clinton, Dutchess Co., New York. They were the parents of ten children, six sons and four daughters. One son, Alford, died at age 2 years, another son, Abner, died in Nauvoo in 1846 age twenty six years, and Phillip died in 1851. The Thorn family had lived in Long Island and Dutchess Co., New York since their Pilgrim ancestors settled there in the early 1600's. The five oldest children were born in Dutchess Co. but the youngest were born in Cayuga Co. on the western border of New York State. The Thorn family all joined the Mormon Church and gathered to Nauvoo, ex- cept the father, Richard Thorn. We do not know whether he ever accepted the gospel. It was a sad thing that she parted from her husband. He later married a widow with two children and moved to Iowa. -

Stillman Pond Biography

Stillman Pond 1847 Utah Pioneer and his Family Biographical Sketch STILLMAN POND A Biographical Sketch by Leon Y. Pond Stillman Pond, an early Utah pioneer, was born 26 October, 1803 at Hubbardston, Worcester County, Mass. (in 1846 Stillman Pond wrote that he was born in Princeton, but the date is not recorded there. It appears at Hubbardston and also at Templeton.) He was a son of Preston Pond and Hannah Bice. His paternal Grandfather was a revolutionary soldier and served on several campaigns. His great grandfather, Ezra Pond, of Franklin, being dissatisfied with religious conditions of that time was a dissenter and a leader of the minority in the Franklin church troubles between 1780 and 85. He was a restless soul. At that time the religions, social and civic affairs of the community were the same, and when Ezra Pond refused to comply with the orders of the Selectmen, he was forced to leave the town. He moved with his family to Hubbardston. Stillman seemed to have inherited this restlessness and dissatisfaction which manifested itself in his frequent moves as a young man. On his Maternal side his grandfather was David Rice who was a grandson of Lt. Paul Moore. one of the Commanders of the American Army in the Battle of Bunkers Hill. All of his ancestors were sincere, honest, and God-fearing pioneers and Puritans, many of whom were Ministers, others were Selectmen of the early towns of New England, Stillman followed in their footsteps as a tiller of the soil. Perhaps few of his ancestors and progenitors ever won national fame and fortune, and fewer still ever brought reproach or shame upon their name. -

EARLY BRANCHES of the CHURCH of JESUS CHRIST of LATTER-DAY SAINTS 1830-1850 Lyman D

EARLY BRANCHES OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS 1830-1850 Lyman D. PW Branches, as an organization of the Church, are first ALBANY, NEW YORK mentioned in the D&C 20:65. Verses 65-67 were added to 8 members. (HC4:6; OP5:107) the D&C by the prophet some time after the original revelation was given I April of 1830. ALEXANDER OR ALEXANDRIA, GENESEE, NEW In 1840 the role of a branch was noL unders~oodas it is YORK today. At tha time a branch contained within its boundaries Jun 1835, 4 members. It belonged to the Black River one or more stakes. This would seem to indicale L-hatche Conference. (HC2:225; IHC6:98) tirst branches of the church should actually be called stakes in the modem sense. (HC4: 143- 144) ALLERTON, OCEAN, NEW JERSEY Approximately 575 branches of the church have been In 1837 there appeared to have been a branch. identitied in the United Sktes and Canada prior to the Utah (Allerron Messenger, Allerton, NJ, 24 Aug J 955) period. Many of hese were abandoned in the 1830s as the church moved to Missouri and Illinois. Others were ALLRED, POTTAWATTAME, IOWA disbanded as the church prepared to move west. In some 2 Jan1 848, list of 13 high priests: Isaac Allred; Moscs cases there was an initial organization, a disorganization Harris; Thomas Richardson; Nathaniel 13. Riggs; William and a reorganization as successive waves of missionary Allridge; John Hanlond; hnyFisher; Edmund Fisher; work and migration hit an area. John Walker; William Faucett; . -

The Refiners Fire Mormon Message

The refiners fire mormon message Continue How to believe the Lord through our trialsIn all of us wants to be some wonderful creation. We want to be sculpted and molded into something worthy and wonderful. The scriptures refer to the fire of the refinery (Malachi 3:2) and the test of faith by fire, which can help us become this way: It is a test of your faith, being much more precious than the gold that perishes, although it will be judged with fire, can be found to praise and honor and glory at the appearance of Jesus Christ: Who has not seen, you love; in which though now you see it is gone, but believe you rejoice with joy unspeakable and full of glory: Getting the end of your faith, even saving your souls (1 Peter 1:7-9). If we were a piece of metal, we would have some impurities naturally inside of us. If the creator wants to work with a clean piece of metal, he would have to expose it to a strong heat and pressure to burn the impurities and leave the refined metal behind to form this metal into something remarkable. Kim Martin was a piece of metal. Her first child was diagnosed with a tumor. Cancer was found in her daughter. Her second son and husband died within a few months of each other. In between all the fire tests, all hammer slamming, Kim began to think she wasn't strong enough. But then she noticed what the Lord was doing -- He was creating something more beautiful out of her life than she could create on her own. -

Challenges and Triumphs of Ground-Penetrating Radar for Studying the Archaeological Resources of Mormon Nauvoo

Studying the Archaeological Resources of Mormon Nauvoo 161 Challenges and Triumphs of Ground-Penetrating Radar for Studying the Archaeological Resources of Mormon Nauvoo John H. McBride, Benjamin C. Pykles, Ryan W. Saltzgiver, Chelsea Richard, and R. William Keach II Nauvoo, Illinois, sits astride a small promontory of land that appears to jut westward into the Mississippi River, reclaiming a formerly swampy area, locally known as “the flats.” The flats rise to about 30 feet (9 meters) above the river level, sloping gently upward to “the bluff,” from which point the prairie JOHN H. MCBRI D E ([email protected]) is a professor in the Department of Geological Sciences at Brigham Young University. He received a PhD from Cornell University and has an interest in applying geophysical techniques to the study of Mormon historical sites. BEN ja MIN C. PYKLES ([email protected]) is a curator of historic sites for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He received a PhD in anthropology with an emphasis in historical archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Excavating Nauvoo: The Mormons and the Rise of Historical Archaeology in America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), and has researched and conducted field work in Nauvoo over the past decade. RY A N W. SA LTZ G IVER ([email protected]) is an MA candidate in anthropology at Brigham Young University. His research focuses on the archaeology of early Mormon historical sites. CHELSE A RICH A R D ([email protected]) is currently a geoarchaeologist in the greater New York City area. -

Episode 22 Part I Transcript Final.Docx

Hank Smith: 00:01 Welcome to Follow Him, a weekly podcast dedicated to helping individuals and families with their Come Follow Me Step. I'm Hank Smith. John Bytheway: 00:09 I'm John Bytheway. Hank Smith: 00:11 We love to learn. John Bytheway: 00:11 We love to laugh. Hank Smith: 00:13 We want to learn and laugh with you. John Bytheway: 00:15 As together, we follow Him. Hank Smith: 00:18 Hello and welcome to another episode of Follow Him. My name is Hank Smith and I'm here with my cohost, the unequaled John Bytheway. Welcome, John. John Bytheway: 00:30 It's always fun to hear the new adjective. Hank Smith: 00:33 I want to mention to everybody listening that you can find us on social media, on Instagram and Facebook. You can get show notes, transcripts, any references for quotes from our episodes on followhim.co, not followhim.com, but Follow Him dot C-O. You can rate and review the podcast. Hank Smith: 00:53 Then I failed to mentioned something early on, John, that I wanted to mention. We have some music that comes in when we start our episodes and then finishes our episodes, and I never mention that that is a song composed by Marshall McDonald, one of my good friends out of seminaries and institutes. So, Marshall McDonald, look him up. He's just a talented, talented musician. Hank Smith: 01:17 Well, John, I'm pretty excited for today. I'm excited for every episode, to be honest, but today, I've been looking forward to for a long time.