Turkey’S Globally Important Biodiversity in Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Shelterwood Logging Maintain Herb Layer Diversity in a Beech Forest in Turkey?

Yılmaz - Yılmaz: Herb layer diversity in a beech forest in Turkey - 487 - CAN SHELTERWOOD LOGGING MAINTAIN HERB LAYER DIVERSITY IN A BEECH FOREST IN TURKEY? YILMAZ, O. Y.1* – YILMAZ, H.2 1Department of Surveying and Cadastre, Faculty of Forestry, Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Istanbul 34473, Turkey 2Ornamental Plant Cultivation Program, Vocational School of Forestry, Istanbul University- Cerrahpaşa, Istanbul 34473, Turkey (phone: +90-212-338-2400; fax: +90-212-338-2428) *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone: +90-212-338-2400; fax: +90-212-226-1113 (Received 9th Sep 2019; accepted 15th Nov 2019) Abstract. The abundance and diversity of forest understory vegetation can be significantly impacted by forest management. Besides having a wide geographical distribution in Turkey, the Oriental beech (Fagus orientalis Lipsky) is also one of the economically important timber species of the country. The aim of this study is to compare the understory herb layer communities of mature and young beech stands which regenerated as a result of the shelterwood method. We studied understory plant species diversity and composition in 16 plots in old and young beech stands in Belgrad Forest near İstanbul, Turkey. We found no significant differences between the two stand types in understory plant diversity but understory species compositions in two stand types were found to be different. Our finding can be useful for forest management planning; by focusing on stand scale to achieve forest management conserving understory plant diversity in a forest. Keywords: Belgrad Forest, understory composition, indicator species, pure beech stands, stand age Introduction Herb layer vegetation is an important component for biodiversity conservation efforts because it contains the majority of vascular plant species diversity and plays a significant role in forest ecosystem functioning (Augusto et al., 2003; Lorenz et al., 2006; Gilliam, 2007; Ellum, 2009). -

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in Forest

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY A B POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis JUNE, 2017 Acknowledgements This paper was prepared by a combined team1 of World Bank staff and consultants, working with local Turkish consultants and stakeholders in close collaboration.2 The team would like to acknowledge the efforts of UDA Consulting in Turkey for the survey’s design and implementation. The team would like to acknowledge the support and design contributions of the Program for Forests (PROFOR), who also funded this study. Additionally, the team would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the General Directorate of Forestry (GDF), who provided guidance and the oversight of information that led to the construction of the survey and sample design. The findings from this paper form an integral part of a much broader engagement with the Turkish GDF through a jointly-produced Forest Policy Note. 1 The Team comprised: Craig M. Meisner (World Bank, Task Team Leader and Sr Environmental Economist), Limin Wang (World Bank, Consultant), Raisa Chandrashekhar Behal (World Bank, Consultant), and Priya Shyamsundar (World Bank, Consultant), Andrew Mitchell (World Bank, Sr Forestry Specialist), and Esra Arikan (World Bank, Sr Environmental Specialist). 2 Local Turkish collaborators included: UDA Consulting for survey implementation and the Central Union of Turkish Forestry Cooperatives (OR-KOOP). CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. -

50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–20 Edition) § 16.14

§ 15.41 50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–20 Edition) Species Common name Serinus canaria ............................................................. Common Canary. 1 Note: Permits are still required for this species under part 17 of this chapter. (b) Non-captive-bred species. The list 16.14 Importation of live or dead amphib- in this paragraph includes species of ians or their eggs. non-captive-bred exotic birds and coun- 16.15 Importation of live reptiles or their tries for which importation into the eggs. United States is not prohibited by sec- Subpart C—Permits tion 15.11. The species are grouped tax- onomically by order, and may only be 16.22 Injurious wildlife permits. imported from the approved country, except as provided under a permit Subpart D—Additional Exemptions issued pursuant to subpart C of this 16.32 Importation by Federal agencies. part. 16.33 Importation of natural-history speci- [59 FR 62262, Dec. 2, 1994, as amended at 61 mens. FR 2093, Jan. 24, 1996; 82 FR 16540, Apr. 5, AUTHORITY: 18 U.S.C. 42. 2017] SOURCE: 39 FR 1169, Jan. 4, 1974, unless oth- erwise noted. Subpart E—Qualifying Facilities Breeding Exotic Birds in Captivity Subpart A—Introduction § 15.41 Criteria for including facilities as qualifying for imports. [Re- § 16.1 Purpose of regulations. served] The regulations contained in this part implement the Lacey Act (18 § 15.42 List of foreign qualifying breed- U.S.C. 42). ing facilities. [Reserved] § 16.2 Scope of regulations. Subpart F—List of Prohibited Spe- The provisions of this part are in ad- cies Not Listed in the Appen- dition to, and are not in lieu of, other dices to the Convention regulations of this subchapter B which may require a permit or prescribe addi- § 15.51 Criteria for including species tional restrictions or conditions for the and countries in the prohibited list. -

Jan 2021 ZSL Stocklist.Pdf (699.26

Zoological Society of London - January 2021 stocklist ZSL LONDON ZOO Status at 01.01.2021 m f unk Invertebrata Aurelia aurita * Moon jellyfish 0 0 150 Pachyclavularia violacea * Purple star coral 0 0 1 Tubipora musica * Organ-pipe coral 0 0 2 Pinnigorgia sp. * Sea fan 0 0 20 Sarcophyton sp. * Leathery soft coral 0 0 5 Sinularia sp. * Leathery soft coral 0 0 18 Sinularia dura * Cabbage leather coral 0 0 4 Sinularia polydactyla * Many-fingered leather coral 0 0 3 Xenia sp. * Yellow star coral 0 0 1 Heliopora coerulea * Blue coral 0 0 12 Entacmaea quadricolor Bladdertipped anemone 0 0 1 Epicystis sp. * Speckled anemone 0 0 1 Phymanthus crucifer * Red beaded anemone 0 0 11 Heteractis sp. * Elegant armed anemone 0 0 1 Stichodactyla tapetum Mini carpet anemone 0 0 1 Discosoma sp. * Umbrella false coral 0 0 21 Rhodactis sp. * Mushroom coral 0 0 8 Ricordea sp. * Emerald false coral 0 0 19 Acropora sp. * Staghorn coral 0 0 115 Acropora humilis * Staghorn coral 0 0 1 Acropora yongei * Staghorn coral 0 0 2 Montipora sp. * Montipora coral 0 0 5 Montipora capricornis * Coral 0 0 5 Montipora confusa * Encrusting coral 0 0 22 Montipora danae * Coral 0 0 23 Montipora digitata * Finger coral 0 0 6 Montipora foliosa * Hard coral 0 0 10 Montipora hodgsoni * Coral 0 0 2 Pocillopora sp. * Cauliflower coral 0 0 27 Seriatopora hystrix * Bird nest coral 0 0 8 Stylophora sp. * Cauliflower coral 0 0 1 Stylophora pistillata * Pink cauliflower coral 0 0 23 Catalaphyllia jardinei * Elegance coral 0 0 4 Euphyllia ancora * Crescent coral 0 0 4 Euphyllia glabrescens * Joker's cap coral 0 0 2 Euphyllia paradivisa * Branching frog spawn 0 0 3 Euphyllia paraancora * Branching hammer coral 0 0 3 Euphyllia yaeyamaensis * Crescent coral 0 0 4 Plerogyra sinuosa * Bubble coral 0 0 1 Duncanopsammia axifuga + Coral 0 0 2 Tubastraea sp. -

A Conservation Reassessment of the Critically Endangered, Lorestan Newt Neurergus Kaiseri (Schmidt 1952) in Iran

Copyright: © This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution–Non Commercial –No Derivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits conditional use for non-commercial and education purposes, provided the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation 9(1): 16- original author and source are credited, and prohibits the deposition of material from www.redlist -arc.org or affiliated websites 25. including www.redlist.arcme.org, including PDFs, images, or text, onto other websites without permission of the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation journal at www.redlist-arc.org A conservation reassessment of the Critically Endangered, Lorestan newt Neurergus kaiseri (Schmidt 1952) in Iran 1* 2 3 1 2 Asghar Mobaraki , Mohsen Amiri , Rahim Alvandi , Masoud Ebrahim Tehrani , Hossein Zarin Kia , Ali 2 4, 5 6 Khoshnamvand , Ali Bali Ehsan Forozanfar , and Robert K Browne 1: Department of Environment, Biodiversity and Wildlife Bureau, PO. Box 14155-7383, Tehran, Iran, 2: Department of Environment Provincial Office in Lorestan, Khoram Abad, Iran, 3: Department of Environment Provincial Office in Khuzestan, Ahvaz, Iran 4: Department of Environment, Habitats and Protected Areas Affairs Bureau, PO. Box 14155-7383, Tehran, Iran, 5: Faculty of Environment, Standard Square, Karaj, 6: Sustainability America, Sarteneja, Belize. Abstract The Lorestan newt (Neurergus kaiseri, Schmidt 1952) is an endemic salamander species to Iran, listed as “Critically Endangered” in the 2006 IUCN Red List due to population declines of 80%, over collection for the pet trade; area of occupancy less than 10 km2, fragmented populations, less than 1,000 adults, and continuing habitat degradation and loss. However, the Red List assessment was limited to surveys only around the type location of N. -

Notes on the Distribution and Abundance of the Endangered Kaiser ’S Mountain Newt , Neurergus Kaiseri (C Audata : Salamandridae ), in Southwestern Iran

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 8(3):724−731. HSuebrpmeittotelodg: i1c aJlu Clyo 2n0se1r2v;a Aticocne apntedd B: 9io Jlouglyy 2013; Published: 31 December 2013. Notes oN the DistributioN aND abuNDaNce of the eNDaNgereD Kaiser ’s MouNtaiN Newt , Neurergus kaiseri (c auData : salaMaNDriDae ), iN southwesterN iraN Mozafar sharifi 1* , h osseiN farasat 1, h osseiN BaraNi -B eiraNv 2, soMaye vaissi 1, and ehsaN foroozaNfar 3 1Razi University Center for Environmental Studies, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Kermanshah 67149, Iran 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran 3Faculty of Environment, Ostandari Square, Karaj, Iran *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] abstract. —the endangered Kaiser’s Mountain Newt, Neurergus kaiseri , is a species endemic to the southern Zagros range in iran. until now, N. kaiseri had been reported from only five localities. the present study describes eight new localities that increase the species’ known range from 212 km 2 (minimum convex polygon) to 789 km 2 at elevations between 930−1395 meters. the localities are generally dispersed; nearest neighbor distances among the 13 localities average 4.61 km (range, 0.93−12.39 km). the streams are separated from one another by steep and rocky terrain with vegetation cover of mature open oak woodland in the west and sparse scrubland or thin oak-pistachio woodland in the central area and east, thus potentially isolating many of the populations from each other. we surveyed 12 of the 13 localities with newts 1−2 times and counted a total of 1,277 adults, post-metamorphic sub-adults, and larvae (mean per stream, 106; range, 2−650) in a total of 4.23 km of stream reaches. -

Salamander Species Listed As Injurious Wildlife Under 50 CFR 16.14 Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus Effective January 28, 2016

Salamander Species Listed as Injurious Wildlife Under 50 CFR 16.14 Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus Effective January 28, 2016 Effective January 28, 2016, both importation into the United States and interstate transportation between States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or any territory or possession of the United States of any live or dead specimen, including parts, of these 20 genera of salamanders are prohibited, except by permit for zoological, educational, medical, or scientific purposes (in accordance with permit conditions) or by Federal agencies without a permit solely for their own use. This action is necessary to protect the interests of wildlife and wildlife resources from the introduction, establishment, and spread of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans into ecosystems of the United States. The listing includes all species in these 20 genera: Chioglossa, Cynops, Euproctus, Hydromantes, Hynobius, Ichthyosaura, Lissotriton, Neurergus, Notophthalmus, Onychodactylus, Paramesotriton, Plethodon, Pleurodeles, Salamandra, Salamandrella, Salamandrina, Siren, Taricha, Triturus, and Tylototriton The species are: (1) Chioglossa lusitanica (golden striped salamander). (2) Cynops chenggongensis (Chenggong fire-bellied newt). (3) Cynops cyanurus (blue-tailed fire-bellied newt). (4) Cynops ensicauda (sword-tailed newt). (5) Cynops fudingensis (Fuding fire-bellied newt). (6) Cynops glaucus (bluish grey newt, Huilan Rongyuan). (7) Cynops orientalis (Oriental fire belly newt, Oriental fire-bellied newt). (8) Cynops orphicus (no common name). (9) Cynops pyrrhogaster (Japanese newt, Japanese fire-bellied newt). (10) Cynops wolterstorffi (Kunming Lake newt). (11) Euproctus montanus (Corsican brook salamander). (12) Euproctus platycephalus (Sardinian brook salamander). (13) Hydromantes ambrosii (Ambrosi salamander). (14) Hydromantes brunus (limestone salamander). (15) Hydromantes flavus (Mount Albo cave salamander). -

Habitat Selection of Small Mammals in a Mixed Forest in Turkey - 133

Bulut et al.: Habitat selection of small mammals in a mixed forest in turkey - 133 - HABITAT SELECTION OF SMALL MAMMALS IN A MIXED FOREST IN TURKEY BULUT, Ş.1* – KARATAŞ, A.2 – AYAŞ, Z.3 1Hitit University, Faculty of Art and Science, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Çorum, Turkey 2Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, Department of Biology, Niğde, Turkey 3Hacettepe University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ankara, Turkey *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; phone: +90-364-227-7000 (Received 25th May 2020; accepted 19th Nov 2020) Abstract. Small mammals is a non-taxonomic subgroup named on the basis of body size of individuals. This study was created from data obtained through the mark-recapture method of small terrestrial mammals in Populus tremula, thermophilic deciduous, steppes, conifer plantations and Abies sp. forest habitats in Turkey. Field studies were performed for a total of 14 months in 2014 and 2015. 758 individuals from seven species were captured in a total of 5250 days in trapping grid studies conducted in a total of 5 different types of habitat by a grid of 5 × 5 traps system. The average capture success in all was calculated as 14.44%. The species affected by temperature data were M. glareolus and D. nitedula. It was found that M. subterraneus showing increasing populations was negatively correlated with temperature. When considering the sex ratios, M. glareolus was under intense male pressure in steppe habitat. Indicator species were determined numerically and M. glareolus, M. subterraneus and D. nitedula were found to be decisive species for different habitats. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Biological Conservation 144 (2011) 2752–2769 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Review Turkey’s globally important biodiversity in crisis ⇑ Çag˘an H. Sßekerciog˘lu a,b, , Sean Anderson c, Erol Akçay d, Rasßit Bilgin e, Özgün Emre Can f, Gürkan Semiz g, Çag˘atay Tavsßanog˘lu h, Mehmet Baki Yokesß i, Anıl Soyumert h, Kahraman Ipekdal_ j, Ismail_ K. Sag˘lam k, Mustafa Yücel l, H. Nüzhet Dalfes m a Department of Biology, University of Utah, 257 South 1400 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0840, USA b KuzeyDog˘a Derneg˘i, Ismail_ Aytemiz Caddesi 161/2, 36200 Kars, Turkey c Environmental Science and Resource Management Program, 1 University Drive, California State University Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA 93012, USA d National Institute -

Timber Legality Risk Assessment Turkey

Timber Legality Risk Assessment Turkey Version 1.0 l September 2018 <MONTH> <YEAR> COUNTRY RISK ASSESSMENTS This risk assessment has been developed by NEPCon with support from the LIFE programme of the European Union, UK aid from the UK government and FSCTM. www.nepcon.org/sourcinghub NEPCon has adopted an “open source” policy to share what we develop to advance sustainability. This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 license. Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this document, to deal in the document without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, and/or distribute copies of the document, subject to the following conditions: The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the document. We would appreciate receiving a copy of any modified version. Disclaimers This Risk Assessment has been produced for educational and informational purposes only. NEPCon is not liable for any reliance placed on this document, or any financial or other loss caused as a result of reliance on information contained herein. The information contained in the Risk Assessment is accurate, to the best of NEPCon’s knowledge, as of the publication date The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. This material has been funded by the UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. -

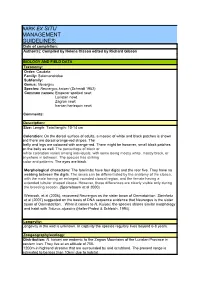

MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES: Date of Completion: Author(S): Compiled by Helena Olsson Edited by Richard Gibson

AARK EX SITU MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES: Date of completion: Author(s): Compiled by Helena Olsson edited by Richard Gibson BIOLOGY AND FIELD DATA Taxonomy: Order: Caudata Family: Salamandridae Subfamily: Genus: Neuergus Species: Neurergus kaiseri (Schmidt 1952) Common names: Emperor spotted newt Luristan newt Zagros newt Iranian harlequin newt Comments: Description: Size: Length: Total length: 10-14 cm Coloration: On the dorsal surface of adults, a mosaic of white and black patches is shown and there are dorsal orange-red stripes. The belly and legs are coloured with orange-red. There might be however, small black patches on the belly as well. The percentage of black or white coloration varies among individuals, with some being mostly white, mostly black, or anywhere in between. The species has striking color and patterns. The eyes are black. Morphological characters: The forelimbs have four digits and the rear five. They have no webbing between the digits. The sexes can be differentiated by the anatomy of the cloaca, with the male having an enlarged, rounded cloacal region, and the female having a extended tubular shaped cloaca. However, these differences are clearly visible only during the breeding season. (Sparreboom et al 2000) Weisrock, et al (2006), recovered Neurergus as the sister taxon of Ommatotriton. Steinfartz et al (2007) suggested on the basis of DNA sequence evidence that Neurergus is the sister taxon of Ommatotriton. When it comes to N. Kaiseri, the species shares similar morphology and habit with Triturus alpestris (Haller-Probst & Schleich, 1994). Longevity: Longevity in the wild is unknown. In captivity the species regulary lives beyond 6-8 years. -

Bantlin, Drew A. 2018.Reintroduction of African Lions to Akagera National Park, Rwanda

Global Reintroduction Perspectives: 2018 Case studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae IUCN/SSC Reintroduction Specialist Group (RSG) i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN/SSC Reintroduction Specialist Group & Environment Agency-Abu Dhabi Copyright: © 2018 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. (ed.) (2018). Global Reintroduction Perspectives: 2018. Case studies from around the globe. IUCN/SSC Reintroduction Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland and Environment Agency, Abu Dhabi, UAE. xiv + 286pp. 6th Edition ISBN: 978-2-8317-1901-6 (PDF) 978-2-8317-1902-3 (print edition) DOI: https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2018.08.en Cover photo: Clockwise starting from top-left: I. Reticulated python, Singapore © ACRES II. Trout cod, Australia © Gunther Schmida (Murray-Darling Basin Authority) III. Yellow-spotted mountain newt, Iran © M. Sharifi IV. Scimitar-horned oryx, Chad © Justin Chuven V. Oregon silverspot butterfly, USA © U.S.