A Crimson Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

Media Awareness

Media Awareness May 2017 1 Introducing our local media Gloucestershire Live (Covers Gloucester Citizen, Gloucestershire Echo and Stroud Life) The Citizen (Daily) Forest Citizen (weekly) Gloucestershire Live Online Daily unique visitors Readership Circulation 30,616 Over 1 Readers 10,944 Majority million unique visitors 30+ accessed Gloucestershire Live in July 2016 Gloucestershire Echo (Daily) Stroud Life (Weekly) Facebook Tewkesbury Echo (weekly) Live Readership Readership Circulation Circulation 20,050 26,277 11,925 9,805 52K likes across two pages (GlosLive and GlosLive what’s on) The online world continues to put pressure on our deadlines Figures as of August 2016 1 Our weeklies The Forester Cotswold Journal Forest Review Gloucester Review (free) Cheltenham Standard (free) Stroud News and Journal Gloucester/ Dursley Gazette Wilts and Glos Standard 2 Radio/Television BBC programmes Listeners Mark Cummings in the morning 79,900 per week Figures taken between Anna King mid-morning(often works with reporter Manpreet Mellhi) January 2016 to June 2016 Dominic Cotton in the afternoon Nicky Price mid-afternoon Demographic Drivetime with Steve Kitchen Typically believed to be people aged 50 and over The commercial The community Television station station BBC Points West ITV West Steve Knibbs Ken Goodwin Heart FM The Breeze GFM http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/england/gloucestershire http://www.itv.com/news/westcountry/ 3 Different types of news Proactive Reactive Media release; Who? What? Media enquires - a no ‘no comment’ policy Where? When? How? Media notes Cabinet/council meetings Photo opportunities Reactive statements – prepared in advance or based on request Broadcast interviews Taken from social media sites Events Campaigns Content (could be video) for social media pages 4 Dealing with the media Councillors represent the views of the public and all councillors can comment on or communicate on any subject they choose at any time. -

The Bel Aire City City Aire Bel the Meant to Reimburse Cities for for Cities Reimburse to Meant Incurred Expenditures Extra from March 1 Through Oct

Valley Center, KS 67147 Center, Valley Main W. 120 • 210 PO Box The Bel Aire VALLEY Permit No. 10 PRSRT. STD. PRSRT. U.S. Postage 67147 PAID CENTER, KS BVol. 15, No. 10 reeze November 2020 Complimentary copy By Chris Strunk people. It is expected to open in Marzano, the company’s director online retailer also announced it Amazon coming2021. of operations. to wasarea opening a similar warehouse Fulfillment Breaking its silence over a For perspective, 17 football “We’re excited for what our in Kansas City, Kan. construction project that has been fields could fit inside the ware- future holds together,” Marzano “We are excited and honored center under in the works for several months, house. said. to have a household name such as Amazon confirmed Oct. 16 that The warehouse will handle Amazon’s official announce- Amazon choose to be here in Park construction it is building a giant fulfillment large items, such as patio fur- ment was made on a Zoom City,” Park City Mayor Ray Mann center in Park City. niture and outdoor equipment. conference call. It included local, said. “… We believe Amazon in Park City The 1 million-square-foot Employee pay will start at $15 state and national leaders. Each warehouse will employ 500 per hour with benefits, said Mark praised Amazon’s decision. The See AMAZON, Page 5 Fun Day in Fall Bel Aire hosted its annual Fall Fun Day Oct. 17 at the Bel Aire Recreation Center. The event included a car show, a petting zoo, children’s games and food. Courtesy photos City to equip all police Bel Aire accepts COVID-19By Taylor Messick Funds can’t funds be used to fill revenue shortfalls but there officersBy Taylor Messick $32,386. -

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA of SCIENCE and OTHER WRITINGS the Rockefeller Institute Press

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA OF SCIENCE AND OTHER WRITINGS The Rockefeller Institute Press IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK 1960 @ 1960 BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 60-13207 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE The Ethical Dilemma of Science Living mechanism 5 The present tendencies and the future compass of physiological science 7 Experiments on frogs and men 24 Scepticism and faith 39 Science, national and international, and the basis of co-operation 45 The use and misuse of science in government 57 Science in Parliament 67 The ethical dilemma of science 72 Science and witchcraft, or, the nature of a university 90 CHAPTER TWO Trailing One's Coat Enemies of knowledge 105 The University of London Council for Psychical Investigation 118 "Hypothecate" versus "Assume" 120 Pharmacy and Medicines Bill (House of Commons) 121 The social sciences 12 5 The useful guinea-pig 127 The Pure Politician 129 Mugwumps 131 The Communists' new weapon- germ warfare 132 Independence in publication 135 ~ CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE About People Bertram Hopkinson 1 39 Hartley Lupton 142 Willem Einthoven 144 The Donnan-Hill Effect (The Mystery of Life) 148 F. W. Lamb 156 Another Englishman's "Thank you" 159 Ivan P. Pavlov 160 E. D. Adrian in the Chair of Physiology at Cambridge 165 Louis Lapicque 168 E. J. Allen 171 William Hartree 173 R. H. Fowler 179 Joseph Barcroft 180 Sir Henry Dale, the Chairman of the Science Committee of the British Council 184 August Krogh 187 Otto Meyerhof 192 Hans Sloane 195 On A. -

28Th February 2020

28th February 2020 We are committed to safeguarding children. Designated Child Protection Officer: Amelia Harding Deputy Child Protection Officers: Tamsin Corline, Kate Davenport, Sam Hill, Zoe Smith Named Governor for Child Protection: Rachel Nolan School Mental Health Award We are delighted to advise that we have been awarded a Bronze Mental Health Award by the Carnegie Centre of Excellence for Mental Health in Schools. The assessors were really impressed with the level of support and care given to the children and acknowledged the real team effort of school staff. Paignton Zoo's Great Big Brick Safari From Saturday 28th March until Tuesday 1st September 2020, Paignton Zoo will be home to over 80 giant wild animal models made from over 1 million LEGO® bricks! From a giant gorilla, a jumbo size elephant and a majestic lion, to marvellous macaws, beautiful butterflies and a cool crocodile, these stunning LEGO® brick animals will form The Great Big Brick Safari Trail for visitors to follow around the zoo. So, here's a question for you… What do you call a life-size tiger made from LEGO® bricks? Paignton Zoo are giving you the chance to name the giant Breeze Tiger made out of LEGO® bricks! You can suggest a name for the tiger by entering at https://www.thebreeze.com/win/win-a-family-pass-to-paignton-zoo/?preview=1&_=42741 and you could win a family pass to Paignton Zoo's Great Big Brick Safari as well as being the one who named the Breeze Tiger! One lucky winner will be chosen and contacted on Monday 9th March. -

Bauer Media Group Phase 1 Decision

Completed acquisitions by Bauer Media Group of certain businesses of Celador Entertainment Limited, Lincs FM Group Limited and Wireless Group Limited, as well as the entire business of UKRD Group Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6809/19; ME/6810/19; ME/6811/19; and ME/6812/19 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 24 July 2019. Full text of the decision published on 30 August 2019. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties or third parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Between 31 January 2019 and 31 March 2019 Heinrich Bauer Verlag KG (trading as Bauer Media Group (Bauer)), through subsidiaries, bought: (a) From Celador Entertainment Limited (Celador), 16 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences (the Celador Acquisition); (b) From Lincs FM Group Limited (Lincs), nine local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, a [] interest in an additional local radio station and associated licences, and interests in the Lincolnshire [] and Suffolk [] digital multiplexes (the Lincs Acquisition); (c) From The Wireless Group Limited (Wireless), 12 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, as well as digital multiplexes in Stoke, Swansea and Bradford (the Wireless Acquisition); and (d) The entire issued share capital of UKRD Group Limited (UKRD) and all of UKRD’s assets, namely ten local radio stations and the associated local 1 FM radio licences, interests in local multiplexes, and UKRD’s 50% interest in First Radio Sales (FRS) (the UKRD Acquisition). -

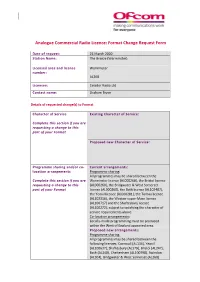

Format Change Request: the Breeze (Warminster)

Analogue Commercial Radio Licence: Format Change Request Form Date of request: 25 March 2020 Station Name: The Breeze (Warminster) Licensed area and licence Warminster number: AL268 Licensee: Celador Radio Ltd Contact name: Graham Bryce Details of requested change(s) to Format Character of Service Existing Character of Service: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Character of Service: Programme sharing and/or co- Current arrangements: location arrangements Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the Complete this section if you are Warminster licence (AL000268), the Bristol licence requesting a change to this (AL000260), the Bridgwater & West Somerset part of your Format licence (AL000260), the Bath licence (AL102407), the Yeovil licence (AL000281), the Torbay licence (AL102316), the Weston-super-Mare licence (AL100717) and the Shaftesbury licence (AL100272), subject to satisfying the character of service requirements above Co-location arrangements: Locally-made programming must be produced within the West of England approved area. Proposed new arrangements: Programme sharing: All programmes may be shared between the following licences: Cornwall (AL136), Yeovil (AL100637), Shaftesbury (AL179), Bristol (AL247), Bath (AL248), Cheltenham (AL100798), Swindon (AL304), Bridgwater & West Somerset (AL260) Torbay (AL102316), Weston-super-Mare (AL100717) and Warminster (AL268). Co-location arrangements: Locally-made programming must be made within the Approved Area of South West England (Bauer amended) Locally-made hours and/or Current obligations: local news bulletins Locally-made hours: At least 7 hours a day during daytime weekdays Complete this section if you are (must include breakfast). requesting a change to this At least 4 hours daytime Saturdays and Sundays. -

Consultation: Bauer Radio Stations in the South of England

Bauer Radio stations in the south of England Request to create a new approved area CONSULTATION: Publication Date: 07 May 2020 Closing Date for Responses: 04 June 2020 Contents Section 1. Overview 1 2. Details and background information 2 3. Consideration of the request 5 Annex A1. Responding to this consultation 6 A2. Ofcom’s consultation principles 8 A3. Consultation coversheet 9 A4. Consultation question 10 A5. Ofcom approved areas 11 A6. Bauer Radio’s request to create a new approved area in the south of England 12 Bauer Radio stations in the south of England – request to create a new approved area 1. Overview Most local analogue commercial radio stations are required to produce a certain number of hours of locally-made programming. Under legislation passed in 2010, these stations are not only able to broadcast their locally-made hours from within their licence area, but may instead broadcast from studios that are based within a larger area approved by Ofcom. These wider areas are known as ‘approved areas’. Stations can also share their local hours of programming with other stations located in the same approved area. In October 2018 Ofcom introduced a new set of larger approved areas in England1 to give stations more flexibility in their broadcasting arrangements. We also said that we would consider requests from licensees to create new, bespoke, approved areas, since the statutory framework allows for an approved area in relation to each local analogue service. What we are consulting on – in brief Bauer Radio has asked Ofcom to approve -

Instruction Manual the Breeze®

Instruction Manual ® The Breeze Model No. 3030-00-000 10700 Medallion Drive, Cincinnati, Ohio 45241-4807 USA © 2021 Gold Medal Products Co. Part No. 110012 The Breeze Model No. 3030-00-000 SAFETY PRECAUTIONS DANGER Machine must be properly grounded to prevent electrical shock to personnel. Failure to do so could result in serious injury, or death. Make sure all machine switches are in the OFF position before plugging the equipment into the receptacle. Keep cord and plug off the ground and away from moisture. Always unplug the equipment before cleaning or servicing. DO NOT immerse any part of this equipment in water. DO NOT use a water jet or excessive water when cleaning. 008_012221 DANGER Improper installation, adjustment, alteration, service, or maintenance can cause property damage, injury, or death. Any alterations to this equipment will void the warranty and may cause a dangerous condition. This appliance is not intended to be operated by means of an external timer or separate remote-control system. NEVER make alterations to this equipment. Read the Installation, Operating, and Maintenance Instructions thoroughly before installing, servicing, or operating this equipment. 014_020416 WARNING Floss head rotates at high speeds. Operator MUST keep hands and face clear of the floss head to avoid injury. Operator must wear eye protection. Keep all spectators at a reasonable distance, and use a Floss Bubble for added customer protection. 015_062714 WARNING Keep all foreign objects out of floss head. To avoid eye injury, DO NOT fill floss head with sugar while the head is on and rotating. 016_010914 WARNING Burn Hazard. -

The Breeze (Winchester)

Analogue Commercial Radio Licence: Format Change Request Form Date of request: 1 March 2019 Station Name: The Breeze (Winchester) Licensed area and licence Winchester number: AL241 Licensee: Nation Broadcasting Investments (South) Ltd Contact name: Martin Mumford Details of requested change(s) to Format Character of Service Existing Character of Service: Complete this section if you are requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new Character of Service: Programme sharing and/or co‐ Current arrangements: location arrangements Programme sharing: Complete this section if you are Co‐location arrangements: requesting a change to this part of your Format Proposed new arrangements: Programme sharing: Co‐location arrangements: Locally‐made hours and/or Current obligations: local news bulletins At least 7 hours a day during daytime weekdays (must include breakfast). At least 4 Complete this section if you are hours daytime Saturdays and Sundays. requesting a change to this Version 9 – amended May 2018 part of your Format Proposed new obligations: At least 3 hours a day during daytime weekdays The holder of an analogue local commercial radio licence may apply to Ofcom to have the station’s Format amended. Any application should be made using the layout shown on this form, and should be in accordance with Ofcom’s published procedures for Format changes.1 Under section 106(1A) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 (as amended), Ofcom may consent to a change of a Format only if it is satisfied that at least one of the following five statutory -

“Reaching 79% of Commercial Radio's Weekly Listeners…” National Coverage

2019 GTN UK is the British division of Global Traffic Network; the leading provider of custom traffic reports to commercial radio and television stations. GTN has similar operations in Australia, Brazil and Canada. GTN is the largest Independent radio network in the UK We offer advertisers access to over 240 radio stations across the country, covering every major conurbation with a solus opportunity enabling your brand to stand out with up to 48% higher ad recall than that of a standard ad break. With both a Traffic & Travel offering, as well as an Entertainment News package, we reach over 28 million adults each week, 80% of all commercial radio’s listeners, during peak listening times only, 0530- 0000. Are your brands global? So are we. Talk to us about a global partnership. Source: Clark Chapman research 2017 RADIO “REACHING 79% OF COMMERCIAL RADIO’S WEEKLY LISTENERS…” NATIONAL COVERAGE 240 radio stations across the UK covering all major conurbations REACH & FREQUENCY Reaching 28 million adults each week, 620 ratings. That’s 79% of commercial radio’s weekly listening. HIGHER ENGAGEMENT With 48% higher ad recall this is the stand-out your brand needs, directly next to “appointment-to-listen” content. BREAKFAST, MORNING, AFTERNOON, DRIVE All advertising is positioned within key radio listening times for maximum reach. 48% HIGHER AD RECALL THAN THAT OF A STANDARD AD BREAK Source: Clark Chapman research NATIONAL/DIGITAL LONDON NORTH EAST Absolute Radio Absolute Radio Capital North East Absolute Radio 70s Kiss Classic FM (North) Absolute -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 2Nd April 2017

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 2nd April 2017 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 54,029,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % All Radio Q 48232 89 18.9 21.2 1023354 100.0 All BBC Radio Q 34182 63 10.0 15.8 540157 52.8 All BBC Radio 15-44 Q 13803 55 5.5 10.1 139700 37.8 All BBC Radio 45+ Q 20379 71 13.9 19.7 400458 61.3 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 31405 58 8.7 15.0 471434 46.1 BBC Local Radio Q 8264 15 1.3 8.3 68723 6.7 All Commercial Radio Q 34534 64 8.4 13.2 456489 44.6 All Commercial Radio 15-44 Q 17663 70 8.7 12.4 219184 59.2 All Commercial Radio 45+ Q 16872 59 8.3 14.1 237305 36.3 All National Commercial1 Q 18709 35 3.0 8.8 163867 16.0 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 26662 49 5.4 11.0 292622 28.6 Other Radio Q 3747 7 0.5 7.1 26708 2.6 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Please note that the information contained within this quarterly data release has yet to be announced or otherwise made public Embargoed until 00.01 am and as such could constitute relevant information for the purposes of section 118 of FSMA and non-public price sensitive 18th May 2017 information for the purposes of the Criminal Justice Act 1993.