HHV-8-Negative/Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman Disease - Uptodate 8/5/19, 2�09 AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mimics of Lymphoma

Mimics of Lymphoma L. Jeffrey Medeiros MD Anderson Cancer Center Mimics of Lymphoma Outline Progressive transformation of GCs Infectious mononucleosis Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease Castleman disease Metastatic seminoma Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma Thymoma Myeloid sarcoma Progressive Transformation of Germinal Centers (GC) Clinical Features Occurs in 3-5% of lymph nodes Any age: 15-30 years old most common Usually localized Cervical LNs # 1 Uncommonly patients can present with generalized lymphadenopathy involved by PTGC Fever and other signs suggest viral etiology Progressive Transformation of GCs Different Stages Early Mid-stage Progressive Transformation of GCs Later Stage Progressive Transformation of GCs IHC Findings CD20 CD21 CD10 BCL2 Progressive Transformation of GCs Histologic Features Often involves small area of LN Large nodules (3-5 times normal) Early stage: Irregular shape Blurring between GC and MZ Later stages: GCs break apart Usually associated with follicular hyperplasia Architecture is not replaced Differential Diagnosis of PTGC NLPHL Nodules replace architecture LP (L&H) cells are present Lymphocyte- Nodules replace architecture rich classical Small residual germinal centers HL, nodular RS+H cells (CD15+ CD30+ LCA-) variant Follicular Numerous follicles lymphoma Back-to-back Into perinodal adipose tissue Uniform population of neoplastic cells PTGC –differential dx Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant HL CD20 NLPHL CD3 Lymphocyte-rich Classical HL Nodular variant CD20 CD15 LRCHL Progressive Transformation of GCs BCL2+ is -

Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Uals Were 2 to 16 Times More Likely to Develop Kaposi Sarcoma Than Were Uninfected Individuals

Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition For Table of Contents, see home page: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/roc Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus uals were 2 to 16 times more likely to develop Kaposi sarcoma than were uninfected individuals. In some studies, the risk of Kaposi sar- CAS No.: none assigned coma increased with increasing viral load of KSHV (Sitas et al. 1999, Known to be a human carcinogen Newton et al. 2003a,b, 2006, Albrecht et al. 2004). Most KSHV-infected patients who develop Kaposi sarcoma have Also known as KSHV or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immune systems compromised either by HIV-1 infection or as a re- Carcinogenicity sult of drug treatments after organ or tissue transplants. The timing of infection with HIV-1 may also play a role in development of Ka- Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is known to be a posi sarcoma. Acquiring HIV-1 infection prior to KSHV infection human carcinogen based on sufficient evidence from studies in hu- may increase the risk of epidemic Kaposi sarcoma by 50% to 100%, mans. This conclusion is based on evidence from epidemiological compared with acquiring HIV-1 infection at the same time as or after and molecular studies, which show that KSHV causes Kaposi sar- KSHV infection. Nevertheless, patients with the classic or endemic coma, primary effusion lymphoma, and a plasmablastic variant of forms of Kaposi sarcoma are not suspected of having suppressed im- multicentric Castleman disease, and on supporting mechanistic data. mune systems, suggesting that immunosuppression is not required KSHV causes cancer, primarily but not exclusively in people with for development of Kaposi sarcoma. -

Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Lesions

1/18/2019 Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Lesions L. Jeffrey Medeiros, MD MD Anderson Cancer Center Outline 2016 classification of Histiocyte Society Langerhans cell histiocytosis / sarcoma Erdheim-Chester disease Juvenile xanthogranuloma Malignant histiocytosis Histiocytic sarcoma Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma Rosai-Dorfman disease Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society 1 1/18/2019 Major Groups of Histiocytic Lesions Group Name L Langerhans-related C Cutaneous and mucocutaneous M Malignant histiocytosis R Rosai-Dorfman disease H Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Blood 127: 2672, 2016 L Group Langerhans cell histiocytosis Indeterminate cell tumor Erdheim-Chester disease S100 Normal Langerhans cells Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis “Old” Terminology Eosinophilic granuloma Single lesion of bone, LN, or skin Hand-Schuller-Christian disease Lytic lesions of skull, exopthalmos, and diabetes insipidus Sidney Farber Letterer-Siwe disease 1903-1973 Widespread visceral disease involving liver, spleen, bone marrow, and other sites Histiocytosis X Umbrella term proposed by Sidney Farber and then Lichtenstein in 1953 Louis Lichtenstein 1906-1977 2 1/18/2019 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Incidence and Disease Distribution Incidence Children: 5-9 x 106 Adults: 1 x 106 Sites of Disease Poor Prognosis Bones 80% Skin 30% Liver Pituitary gland 25% Spleen Liver 15% Bone marrow Spleen 15% Bone Marrow 15% High-risk organs Lymph nodes 10% CNS <5% Blood 127: 2672, 2016 N Engl J Med -

ASCIA WAID Program

Western Australian Immunology Day Clinical Grand Rounds (CGR) Abstracts Saturday 14 November 2020 Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research McCusker Auditorium, 6 Verdun Street, Nedlands WA Time Clinical Grand Rounds (CGR) Speakers Chairs: A/Professor Richard Loh, Dr Tiffany Hughes (SA) Dr Nicola Benwell (WA) CGR cases presented Dr Peter Bradhurst (NSW) by advanced trainees Dr Luckshman Ganeshanandan (WA) Dr Alice Grey (NSW) Each presenter has been allocated 10 13.30 – 15.00 minutes, including 7 minutes for the Dr Lisa Horgan (NSW) presentation and 3 minutes for Dr Adrian Lee (NSW) questions. Dr Natasha Moseley (WA) Dr Claire Reynolds (SA) Dr Alex Stoyanov (NSW) LOSING MY VOICE Dr Nicola Benwell (WA) Granulomatosis polyangiitis (GPA) is one of the ANCA positive small-vessel necrotising granulomatous vasculitides with diverse organ involvement most frequently involving the ear, nose, throat, lungs and kidneys. Severe stricturing disease of the tracheobronchial tree is an uncommon manifestation of this syndrome, characterised by its predilection towards young, female patients that may cause progression of stenosis that is discordant to apparent serological and clinical response in other affected organs to systemic immunosuppression. We present the case of a young 19 year old university student with GPA whose original presentation included sinus and pulmonary disease with PR-3 seropositivity. Induction of remission with high dose corticosteroids and rituximab was followed by a brief period of remission over three months. The following 2 months were characterised by fluctuating clinical course secondary to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and rapid development of airway and life threatening tracheobronchial stenoses (TBS). This was in the absence of elevation in PR3 antibody level or reappearance of manifestations of her disease outside her tracheobronchial tree. -

Japanese Variant of Multicentric Castleman's Disease

J Clin Exp Hematop Vol. 53, No. 1, June 2013 Case Study Japanese Variant of Multicentric Castleman’s Disease Associated With Serositis and Thrombocytopenia ― A Report of Two Cases: Is TAFRO Syndrome (Castleman- Kojima Disease) a Distinct Clinicopathological Entity? Yasufumi Masaki,1) Akio Nakajima,1) Haruka Iwao,1) Nozomu Kurose,2) Tomomi Sato,1) Takuji Nakamura,1) Miyuki Miki,1) Tomoyuki Sakai,1) Takafumi Kawanami,1) Toshioki Sawaki,1) Yoshimasa Fujita,1) Masao Tanaka,1) Toshihiro Fukushima,1) Toshiro Okazaki,1) and Hisanori Umehara1) Multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) is a polyclonal lymphoproliferative disorder that manifests as marked hyper-g- globulinemia, severe inflammation, anemia, and thrombocytosis. Recently, Takai et al. reported a new disease concept, TAFRO syndrome, named from thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis, and organomegaly. Furthermore, Kojima et al. reported Japanese MCD cases with effusion and thrombocytopenia (Castleman-Kojima disease). Here, we report two cases of MCD associated with marked pleural effusion, ascites, and thrombocytopenia, and discuss the independence of the TAFRO syndrome (Castleman-Kojima disease). Case 1: A 57-year-old woman had fever, anemia, anasarca, and some small cervical lymphadenopathy. Although she had been administered steroid therapy, and full-coverage antibiotics, her general condition, including fever, systemic inflammation, and anasarca, deteriorated steadily. We administered chemotherapy [CHOEP (cyclo- phosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisolone) regimen], but despite a transient improvement, she died due to septic shock. Case 2: A 73-year-old man with a history of aplastic anemia and remission presented with fever, severe inflammation, and anasarca. Prednisolone was administered (15 mg daily), and his hyperinflammation once improved. -

Diagnosis and Management of Castleman Disease Jacob D

Castleman disease is an uncommon and heterogeneous lymphoproliferative disorder for which management is rapidly evolving. Gum Drop Mushrooms. Photograph courtesy of Sherri Damlo. www.damloedits.com. Diagnosis and Management of Castleman Disease Jacob D. Soumerai, MD, Aliyah R. Sohani, MD, and Jeremy S. Abramson, MD Background: Castleman disease is an uncommon lymphoproliferative disorder characterized as either unicentric or multicentric. Unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) is localized and carries an excellent prognosis, whereas multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) is a systemic disease occurring most commonly in the setting of HIV infection and is associated with human herpesvirus 8. MCD has been associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, and the therapeutic landscape for its management continues to evolve. Methods: The available medical literature on UCD and MCD was reviewed. The clinical presentation and pathological diagnosis of Castleman disease was reviewed, along with associated disorders such as certain malignancies and autoimmune complications. Results: Surgical resection remains the standard therapy for UCD, while systemic therapies are required for the management of MCD. Rituximab monotherapy is the mainstay of therapy; however, novel therapies targeting interleukin 6 may represent a treatment option in the near future. Antiviral strategies as well as single-agent and combination chemotherapy with glucocorticoids are established systemic therapies. The management of Castleman disease also requires careful attention to potential concomitant infections, malignancies, and associated syndromes. Conclusions: UCD and MCD constitute uncommon but well-defined clinicopathologic entities. Although UCD is typically well controlled with local therapy, MCD continues to pose formidable challenges in management. We address historical chemotherapy-based approaches to this disease as well as recently developed targeted therapies, including rituximab and siltuximab, that have improved the outcome for newly diagnosed patients. -

Rheumatology

THE AMERICAN BOARD OF PEDIATRICS® CONTENT OUTLINE Pediatric Rheumatology Subspecialty In-Training, Certification, and Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Examinations INTRODUCTION This document was prepared by the American Board of Pediatrics Subboard of Pediatric Rheumatology for the purpose of developing in-training, certification, and maintenance of certification examinations. The outline defines the body of knowledge from which the Subboard samples to prepare its examinations. The content specification statements located under each category of the outline are used by item writers to develop questions for the examinations; they broadly address the specific elements of knowledge within each section of the outline. Pediatric Rheumatology Each Pediatric Rheumatology exam is built to the same specifications, also known as the blueprint. This blueprint is used to ensure that, for the initial certification and in-training exams, each exam measures the same depth and breadth of content knowledge. Similarly, the blueprint ensures that the same is true for each Maintenance of Certification exam form. The table below shows the percentage of questions from each of the content domains that will appear on an exam. Please note that the percentages are approximate; actual content may vary. Initial Maintenance of Content Domains Certification Certification Exam Exam 1. Core Knowledge in Scholarly Activities 5% 4% 2. Etiology and Pathophysiology 8% 7% 3. Drug Therapy 10% 12% 4. Musculoskeletal Pain 4% 4% 5. Juvenile Arthritis 18% 18% 6. SLE and Related Disorders 12% 12% 7. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myositis 6.5% 6.5% 8. Vasculitis 7% 7% 9. Sclerodermas and Related Disorders 5% 5% 10. Autoinflammatory Diseases 5% 5% 11. Primary Immunodeficiencies and Other 2% 2% Disorders Associated With Inflammatory and Autoimmune Manifestations 12. -

Treating Castleman Disease How Is Castleman Disease Treated?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Treating Castleman Disease How is Castleman disease treated? Several types of treatment can be used to treat Castleman disease, including: ● Surgery for Castleman Disease ● Radiation Therapy for Castleman Disease ● Corticosteroids for Castleman Disease ● Chemotherapy for Castleman Disease ● Immunotherapy for Castleman Disease ● Anti-viral Drugs for Castleman Disease Common treatment approaches Your treatment options will be based on whether the CD is localized (unicentric) or multicentric, as well as other factors when these are important. Because CD is rare, it has been hard to do studies to learn the best ways to treat it. Of course, no two patients are exactly alike, so treatment is tailored to each person’s situation. ● Treatment of Localized (Unicentric) Castleman Disease ● Treatment of Multicentric Castleman Disease Who treats Castleman disease? Based on your treatment options, you might have different types of doctors on your treatment team, including: ● A surgeon ● A hematologist: a doctor who treats disorders of the blood and lymph system, 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 including CD ● A medical oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer and similar diseases with medicines ● A radiation oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer and similar diseases with radiation therapy You might have other specialists on your treatment team as well, including physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), nurses, psychologists, nutrition specialists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and other health professionals. 1 ● Health Professionals Associated With Cancer Care Making treatment decisions It’s important to discuss all of your treatment options, including the goals of treatment and possible side effects, with your doctors to help make the decision that best fits your needs. -

HHV8-Positive Castleman Disease and in Situ Mantle Cell Neoplasia Within Dermatopathic Lymphadenitis, in Longstanding Psoriasis

diagnostics Interesting Images HHV8-Positive Castleman Disease and In Situ Mantle Cell Neoplasia within Dermatopathic Lymphadenitis, in Longstanding Psoriasis Magda Zanelli 1,* , Luca Stingeni 2 , Maurizio Zizzo 3,4, Giovanni Martino 5, Francesca Sanguedolce 6, Andrea Marra 7, Barbara Crescenzi 8, Stefano A. Pileri 9 and Stefano Ascani 5 1 Pathology Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42112 Reggio Emilia, Italy 2 Dermatology Section, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia, 06129 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] 3 Surgical Oncology Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42122 Reggio Emilia, Italy; [email protected] 4 Clinical and Experimental Medicine PhD Program, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, 41121 Modena, Italy 5 Pathology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria di Terni, University of Perugia, 05100 Terni, Italy; [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (S.A.) 6 Pathology Unit, Policlinico Riuniti, University of Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] 7 Centre of Hemato-Oncology Research (CREO), Institute of Hematology, University and Hospital of Perugia, 06129 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] 8 Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, CREO, Azienda Ospedaliera di Perugia, University of Perugia, 06129 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] Citation: Zanelli, M.; Stingeni, L.; 9 Haematopathology Division, European Institute of Oncology—IEO IRCCS, 20141 Milan, Italy; Zizzo, M.; Martino, G.; Sanguedolce, [email protected] F.; Marra, A.; Crescenzi, B.; Pileri, * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0522-296372; Fax: +39-0522-296945 S.A.; Ascani, S. HHV8-Positive Castleman Disease and In Situ Mantle Abstract: A 73-year-old man presented with multiple lymphadenopathy. -

Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging of Castleman Disease Detection and Diagnosis

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging of Castleman Disease Detection and Diagnosis Some people with Castleman disease may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that is not always the case. ● Signs and Symptoms of Castleman Disease ● Tests for Castleman Disease Staging and Outlook (Prognosis) Learn how staging provides information about the extent of disease and anticipated response to treatment. ● Castleman Disease Stages ● Survival Rates for Castleman Disease Questions To Ask About Castleman Disease Here are some questions you can ask to help you better understand your diagnosis and treatment options. ● Questions to Ask About Castleman Disease 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Signs and Symptoms of Castleman Disease Castleman disease (CD) can cause a lot of different types of symptoms, and in some people it might not cause any symptoms at all. If symptoms do occur, they are often like those seen with other diseases, such as infections, autoimmune diseases, or even some types of cancer. Because of this, doctors might not suspect CD at first. Common symptoms of localized CD In the localized form of CD, symptoms are found in a particular part of the body. Localized CD often starts as an enlarged lymph node. If the node is just under the skin, such as in the neck or underarm area, it might be seen or felt as a lump. But if it’s in the chest or abdomen (belly), it might not be noticed until it grows large enough to cause other symptoms: ● An enlarged node in the chest might press on the windpipe, which could cause trouble breathing, wheezing, a cough, or a feeling of fullness in the chest. -

Castleman Disease Pathogenesis

Castleman Disease Pathogenesis David C. Fajgenbaum, MD, MBA, MSc*, Dustin Shilling, PhD KEYWORDS Castleman disease Lymphoproliferative disorder HHV-8 POEMS TAFRO Cytokine storm KEY POINTS Castleman disease (CD) is subclassified based on the number of enlarged lymph nodes, Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) infection status, and clinical presentation. The pathogenesis of unicentric CD (adenopathy of a single region of lymph nodes) is most likely driven by a neoplastic follicular dendritic cell population. HHV-8–associated multicentric CD (adenopathy of multiple regions of lymph nodes) pathogenesis is virally driven, whereas polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder, and skin changes (POEMS)–associated multicentric CD (MCD) pathogenesis is driven by a monoclonal plasma cell population. Idiopathic MCD is poorly understood, although clinical data suggest a pathologic role for interleukin-6 in a subset of patients. INTRODUCTION Castleman disease (CD) describes a heterogeneous group of disorders defined by shared lymph node histopathological features, including atrophic or hyperplastic germinal centers, prominent follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), hypervascularization, polyclonal lymphoproliferation, and/or polytypic plasmacytosis.1 Complicating diag- nosis, these histopathologic features are not unique to CD but can be observed in other diseases as well.2 Each subtype of CD has varying clinical features, causes, treatments, and outcomes. This article establishes the nomenclature required to discuss the different subtypes of CD (Fig. 1) and provides a summary of our current Disclosure: D.C. Fajgenbaum receives research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. D. Shilling has nothing to disclose. Division of Translational Medicine and Human Genetics, Hospital of the University of Pennsyl- vania, 3400 Spruce Street, Silverstein 5, Suite S05094, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA * Corresponding author. -

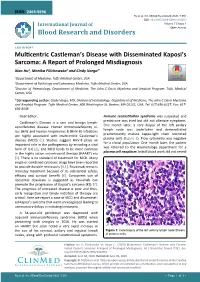

Multicentric Castleman's Disease with Disseminated Kaposi's Sarcoma

ISSN: 2469-5696 Hu et al. Int J Blood Res Disord 2020, 7:051 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5696/1410051 International Journal of Volume 7 | Issue 1 Open Access Blood Research and Disorders CASE REPORT Multicentric Castleman’s Disease with Disseminated Kaposi’s Sarcoma: A Report of Prolonged Misdiagnosis Xiao Hu1, Monika Pilichowska2 and Cindy Varga3* Check for 1Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, USA updates 2Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, USA 3Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, The John C Davis Myeloma and Amyloid Program, Tufts Medical Center, USA *Corresponding author: Cindy Varga, MD, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, The John C Davis Myeloma and Amyloid Program, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington St, Boston, MA 02111, USA, Tel: 617-636-6227, Fax: 617- 636-8538 Dear Editor, Immune reconstitution syndrome was suspected and prednisone was tried but did not alleviate symptoms. Castleman’s Disease is a rare and benign lymph- One month later, a core biopsy of the left axillary oproliferative disease. Human immunodeficiency vi- lymph node was undertaken and demonstrated rus (HIV) and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infections predominantly mature kappa-light chain restricted are highly associated with multicentric Castleman’s plasma cells (Figure 1). Flow cytometry was negative disease (MCD) [1]. Studies suggest HHV-8 plays an for a clonal population. One month later, the patient important role in the pathogenesis by encoding a viral was referred to the Haematology department for a form of IL-6 [2], and MCD tends to be more common plasma cell neoplasm. Initial blood work did not reveal in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era [3].