Castleman Disease Pathogenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of NS1 Antibodies in the Pathogenesis of Acute Secondary Dengue Infection

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07667-z OPEN Role of NS1 antibodies in the pathogenesis of acute secondary dengue infection Deshni Jayathilaka1, Laksiri Gomes1, Chandima Jeewandara1, Geethal.S.Bandara Jayarathna1, Dhanushka Herath1, Pathum Asela Perera1, Samitha Fernando1, Ananda Wijewickrama2, Clare S. Hardman3, Graham S. Ogg3 & Gathsaurie Neelika Malavige 1,3 The role of NS1-specific antibodies in the pathogenesis of dengue virus infection is poorly 1234567890():,; understood. Here we investigate the immunoglobulin responses of patients with dengue fever (DF) and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) to NS1. Antibody responses to recombinant-NS1 are assessed in serum samples throughout illness of patients with acute secondary DENV1 and DENV2 infection by ELISA. NS1 antibody titres are significantly higher in patients with DHF compared to those with DF for both serotypes, during the critical phase of illness. Furthermore, during both acute secondary DENV1 and DENV2 infection, the antibody repertoire of DF and DHF patients is directed towards distinct regions of the NS1 protein. In addition, healthy individuals, with past non-severe dengue infection have a similar antibody repertoire as those with mild acute infection (DF). Therefore, antibodies that target specific NS1 epitopes could predict disease severity and be of potential benefit in aiding vaccine and treatment design. 1 Centre for Dengue Research, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda 10100, Sri Lanka. 2 National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Angoda 10250, Sri Lanka. 3 MRC Human Immunology Unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford OX3 9DS, UK. These authors contributed equally: Deshni Jayathilaka, Laksiri Gomes. The authors jointly supervised this work: Graham S. -

Corneal Endotheliitis with Cytomegalovirus Infection of Persisted

Correspondence 1105 Sir, resulted in gradual decreases of KPs, but graft oedema Corneal endotheliitis with cytomegalovirus infection of persisted. Vision decreased to 20/2000. corneal stroma The patient underwent a second keratoplasty combined with cataract surgery in August 2007. Although involvement of cytomegalovirus (CMV) in The aqueous humour was tested for polymerase corneal endotheliitis was recently reported, the chain reaction to detect HSV, VZV, or CMV; a positive pathogenesis of this disease remains uncertain.1–8 Here, result being obtained only for CMV-DNA. Pathological we report a case of corneal endotheliitis with CMV examination demonstrated granular deposits in the infection in the corneal stroma. deep stroma, which was positive for CMV by immunohistochemistry (Figures 2a and b). The cells showed a typical ‘owl’s eye’ morphology (Figure 2c). Case We commenced systemic gancyclovir at 10 mg per day A 44-year-old man was referred for a gradual decrease in for 7 days, followed by topical 0.5% gancyclovir eye vision with a history of recurrent iritis with unknown drops six times a day. With the postoperative follow-up aetiology. The corrected visual acuity in his right eye was period of 20 months, the graft remained clear without 20/200. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed diffuse corneal KPs (Figure 1d). The patient has been treated with oedema with pigmented keratic precipitates (KPs) gancyclovir eye drops t.i.d. to date. His visual acuity without anterior chamber cellular reaction (Figure 1a). improved to 20/20, and endothelial density was The patient had undergone penetrating keratoplasty in 2300/mm2. Repeated PCR in aqueous humour for August 2006, and pathological examination showed non- CMV yielded a negative result in the 10th week. -

Pathology and Pathogenesis of SARS-Cov-2 Associated with Fatal Coronavirus Disease, United States Roosecelis B

Pathology and Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with Fatal Coronavirus Disease, United States Roosecelis B. Martines,1 Jana M. Ritter,1 Eduard Matkovic, Joy Gary, Brigid C. Bollweg, Hannah Bullock, Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Luciana Silva-Flannery, Josilene N. Seixas, Sarah Reagan-Steiner, Timothy Uyeki, Amy Denison, Julu Bhatnagar, Wun-Ju Shieh, Sherif R. Zaki; COVID-19 Pathology Working Group2 An ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease (CO- United States; since then, all 50 US states, District of VID-19) is caused by infection with severe acute respi- Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Is- ratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Charac- lands, and US Virgin Islands have confirmed cases of terization of the histopathology and cellular localization COVID-19 (2–4). of SARS-CoV-2 in the tissues of patients with fatal CO- Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-strand- VID-19 is critical to further understand its pathogenesis ed RNA viruses that infect many animals; human- and transmission and for public health prevention mea- adapted viruses likely are introduced through zoo- sures. We report clinicopathologic, immunohistochemi- notic transmission from animal reservoirs (5,6). Most cal, and electron microscopic findings in tissues from known human coronaviruses are associated with 8 fatal laboratory-confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 in- mild upper respiratory illness. SARS-CoV-2 belongs fection in the United States. All cases except 1 were in to the group of betacoronaviruses that includes severe residents of long-term care facilities. In these patients, SARS-CoV-2 infected epithelium of the upper and lower acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) airways with diffuse alveolar damage as the predominant and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus pulmonary pathology. -

Mimics of Lymphoma

Mimics of Lymphoma L. Jeffrey Medeiros MD Anderson Cancer Center Mimics of Lymphoma Outline Progressive transformation of GCs Infectious mononucleosis Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease Castleman disease Metastatic seminoma Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma Thymoma Myeloid sarcoma Progressive Transformation of Germinal Centers (GC) Clinical Features Occurs in 3-5% of lymph nodes Any age: 15-30 years old most common Usually localized Cervical LNs # 1 Uncommonly patients can present with generalized lymphadenopathy involved by PTGC Fever and other signs suggest viral etiology Progressive Transformation of GCs Different Stages Early Mid-stage Progressive Transformation of GCs Later Stage Progressive Transformation of GCs IHC Findings CD20 CD21 CD10 BCL2 Progressive Transformation of GCs Histologic Features Often involves small area of LN Large nodules (3-5 times normal) Early stage: Irregular shape Blurring between GC and MZ Later stages: GCs break apart Usually associated with follicular hyperplasia Architecture is not replaced Differential Diagnosis of PTGC NLPHL Nodules replace architecture LP (L&H) cells are present Lymphocyte- Nodules replace architecture rich classical Small residual germinal centers HL, nodular RS+H cells (CD15+ CD30+ LCA-) variant Follicular Numerous follicles lymphoma Back-to-back Into perinodal adipose tissue Uniform population of neoplastic cells PTGC –differential dx Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant HL CD20 NLPHL CD3 Lymphocyte-rich Classical HL Nodular variant CD20 CD15 LRCHL Progressive Transformation of GCs BCL2+ is -

Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Uals Were 2 to 16 Times More Likely to Develop Kaposi Sarcoma Than Were Uninfected Individuals

Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition For Table of Contents, see home page: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/roc Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus uals were 2 to 16 times more likely to develop Kaposi sarcoma than were uninfected individuals. In some studies, the risk of Kaposi sar- CAS No.: none assigned coma increased with increasing viral load of KSHV (Sitas et al. 1999, Known to be a human carcinogen Newton et al. 2003a,b, 2006, Albrecht et al. 2004). Most KSHV-infected patients who develop Kaposi sarcoma have Also known as KSHV or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immune systems compromised either by HIV-1 infection or as a re- Carcinogenicity sult of drug treatments after organ or tissue transplants. The timing of infection with HIV-1 may also play a role in development of Ka- Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is known to be a posi sarcoma. Acquiring HIV-1 infection prior to KSHV infection human carcinogen based on sufficient evidence from studies in hu- may increase the risk of epidemic Kaposi sarcoma by 50% to 100%, mans. This conclusion is based on evidence from epidemiological compared with acquiring HIV-1 infection at the same time as or after and molecular studies, which show that KSHV causes Kaposi sar- KSHV infection. Nevertheless, patients with the classic or endemic coma, primary effusion lymphoma, and a plasmablastic variant of forms of Kaposi sarcoma are not suspected of having suppressed im- multicentric Castleman disease, and on supporting mechanistic data. mune systems, suggesting that immunosuppression is not required KSHV causes cancer, primarily but not exclusively in people with for development of Kaposi sarcoma. -

Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Lesions

1/18/2019 Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Lesions L. Jeffrey Medeiros, MD MD Anderson Cancer Center Outline 2016 classification of Histiocyte Society Langerhans cell histiocytosis / sarcoma Erdheim-Chester disease Juvenile xanthogranuloma Malignant histiocytosis Histiocytic sarcoma Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma Rosai-Dorfman disease Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society 1 1/18/2019 Major Groups of Histiocytic Lesions Group Name L Langerhans-related C Cutaneous and mucocutaneous M Malignant histiocytosis R Rosai-Dorfman disease H Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Blood 127: 2672, 2016 L Group Langerhans cell histiocytosis Indeterminate cell tumor Erdheim-Chester disease S100 Normal Langerhans cells Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis “Old” Terminology Eosinophilic granuloma Single lesion of bone, LN, or skin Hand-Schuller-Christian disease Lytic lesions of skull, exopthalmos, and diabetes insipidus Sidney Farber Letterer-Siwe disease 1903-1973 Widespread visceral disease involving liver, spleen, bone marrow, and other sites Histiocytosis X Umbrella term proposed by Sidney Farber and then Lichtenstein in 1953 Louis Lichtenstein 1906-1977 2 1/18/2019 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Incidence and Disease Distribution Incidence Children: 5-9 x 106 Adults: 1 x 106 Sites of Disease Poor Prognosis Bones 80% Skin 30% Liver Pituitary gland 25% Spleen Liver 15% Bone marrow Spleen 15% Bone Marrow 15% High-risk organs Lymph nodes 10% CNS <5% Blood 127: 2672, 2016 N Engl J Med -

Overview of Pathology and Its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz

MEDICAL SCIENCES – Vol.I -Overview of Pathology and its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz OVERVIEW OF PATHOLOGY AND ITS RELATED DISCIPLINES Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz Cairo University, Kasr El Ainy Hospital, Egypt Keywords: Pathology, Pathology disciplines, Pathology techniques, Ancillary diagnostic methods, General Pathology, Special Pathology Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Pathology coverage 1.1.1 Etiology and Pathogenesis of a Disease 1.1.2 Manifestations of Disease (Lesions) 1.1.3 Phases Of A Disease Process (Course) 1.2 Physician’s approach to patient 1.3 Types of pathologists and affiliated specialties 1.4 Role of pathologist 2. Pathology and its related disciplines 2.1 Cytology 2.1.1 Cytology Samples 2.1.2 Technical Aspects 2.1.3 Examination of Sample and Diagnosis 3. Pathology techniques and ancillary diagnostic methods 3.1 Macroscopic pathology 3.2 Light Microscopy 3.3 Polarizing light microscopy 3.4 Electron microscopy (EM) 3.5 Confocal Microscopy 3.6 Frozen section 3.7 Cyto/histochemistry 3.8 Immunocyto/histochemical methods 3.9 Molecular and genetic methods of diagnosis 3.10 Quantitative methods 4. Types of tests used in pathology 4.1 DiagnosticUNESCO tests – EOLSS 4.2 Quantitative tests 4.3 Prognostic tests 5. The scope of SAMPLEpathology & its main divisions CHAPTERS 6. Conclusions Glossary Bibliography Biographical sketch Summary Pathology is the science of disease. It deals with deviations from normal body function and ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) MEDICAL SCIENCES – Vol.I -Overview of Pathology and its Related Disciplines - Soheir Mahmoud Mahfouz structure. Many disciplines are involved in the study of disease, as it is necessary to understand the complex causes and effects of various disorders that affect the organs and body as a whole. -

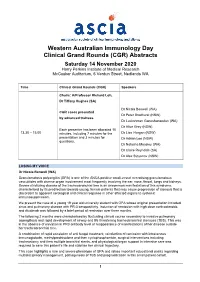

ASCIA WAID Program

Western Australian Immunology Day Clinical Grand Rounds (CGR) Abstracts Saturday 14 November 2020 Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research McCusker Auditorium, 6 Verdun Street, Nedlands WA Time Clinical Grand Rounds (CGR) Speakers Chairs: A/Professor Richard Loh, Dr Tiffany Hughes (SA) Dr Nicola Benwell (WA) CGR cases presented Dr Peter Bradhurst (NSW) by advanced trainees Dr Luckshman Ganeshanandan (WA) Dr Alice Grey (NSW) Each presenter has been allocated 10 13.30 – 15.00 minutes, including 7 minutes for the Dr Lisa Horgan (NSW) presentation and 3 minutes for Dr Adrian Lee (NSW) questions. Dr Natasha Moseley (WA) Dr Claire Reynolds (SA) Dr Alex Stoyanov (NSW) LOSING MY VOICE Dr Nicola Benwell (WA) Granulomatosis polyangiitis (GPA) is one of the ANCA positive small-vessel necrotising granulomatous vasculitides with diverse organ involvement most frequently involving the ear, nose, throat, lungs and kidneys. Severe stricturing disease of the tracheobronchial tree is an uncommon manifestation of this syndrome, characterised by its predilection towards young, female patients that may cause progression of stenosis that is discordant to apparent serological and clinical response in other affected organs to systemic immunosuppression. We present the case of a young 19 year old university student with GPA whose original presentation included sinus and pulmonary disease with PR-3 seropositivity. Induction of remission with high dose corticosteroids and rituximab was followed by a brief period of remission over three months. The following 2 months were characterised by fluctuating clinical course secondary to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and rapid development of airway and life threatening tracheobronchial stenoses (TBS). This was in the absence of elevation in PR3 antibody level or reappearance of manifestations of her disease outside her tracheobronchial tree. -

Chapter 2, Transmission and Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis (TB)

Chapter 2 Transmission and Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis Table of Contents Chapter Objectives . 19 Introduction . 21 Transmission of TB . 21 Pathogenesis of TB . 26 Drug-Resistant TB (MDR and XDR) . 35 TB Classification System . 39 Chapter Summary . 41 References . 43 Chapter Objectives After working through this chapter, you should be able to • Identify ways in which tuberculosis (TB) is spread; • Describe the pathogenesis of TB; • Identify conditions that increase the risk of TB infection progressing to TB disease; • Define drug resistance; and • Describe the TB classification system. Chapter 2: Transmission and Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis 19 Introduction TB is an airborne disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) (Figure 2.1). M. tuberculosis and seven very closely related mycobacterial species (M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, M. caprae, M. pinnipedii, M. canetti and M. mungi) together comprise what is known as the M. tuberculosis complex. Most, but not all, of these species have been found to cause disease in humans. In the United States, the majority of TB cases are caused by M. tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis organisms are also called tubercle bacilli. Figure 2.1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis Transmission of TB M. tuberculosis is carried in airborne particles, called droplet nuclei, of 1– 5 microns in diameter. Infectious droplet nuclei are generated when persons who have pulmonary or laryngeal TB disease cough, sneeze, shout, or sing. Depending on the environment, these tiny particles can remain suspended in the air for several hours. M. tuberculosis is transmitted through the air, not by surface contact. Transmission occurs when a person inhales droplet nuclei containing M. -

CANCER EPIDEMIOLOGY and PATHOGENESIS (EPID 770) SPRING 2016, T/Th 9:30-10:45 Melissa Troester, [email protected]

CANCER EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS (EPID 770) SPRING 2016, T/Th 9:30-10:45 Melissa Troester, [email protected] Course objective: The objective of this course is to provide a framework for understanding and critically evaluating epidemiologic literature. The course will cover cancer statistics, major risk factors for cancer, mechanisms of carcinogenesis, biomarkers in cancer research, and current controversies in cancer research. Students will gain background knowledge of cancer biology and epidemiology needed to interpret and critique cancer prevention research and will develop and practice skills in critiquing literature, resolving discrepancies between studies, and identifying knowledge gaps. Readings: Assigned readings and study questions will be provided through Sakai. There is no assigned textbook for the course, but these texts may be useful as references: Nasca and Pastides. Fundamentals of Cancer Epidemiology (2nd Ed). Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury, MA 2008. Schottenfeld and Fraumeni. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, (3rd Ed). Oxford, New York, NY 2006. Course requirements: Class participation (20%): Each class period will include a discussion of assigned readings and study questions. Students are required to complete reading and/or homework assignments prior to class. Several class sessions are set up as student-led discussion. Peer evaluation sheets will be collected for panel discussants, and both the evaluator and the discussant will receive a grade based on these evaluations. Literature critique (20% X 2): Two peer-review critiques will be written during the semester on assigned articles. The articles will be taken from the current literature and the written critique should resemble a critique that would be written as a reviewer for a scientific journal. -

Medical Bacteriology

LECTURE NOTES Degree and Diploma Programs For Environmental Health Students Medical Bacteriology Abilo Tadesse, Meseret Alem University of Gondar In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education September 2006 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2006 by Abilo Tadesse, Meseret Alem All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. PREFACE Text book on Medical Bacteriology for Medical Laboratory Technology students are not available as need, so this lecture note will alleviate the acute shortage of text books and reference materials on medical bacteriology. -

Molecular Pathological Epidemiology in Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Submit a Manuscript: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/ World J Hepatol 2016 September 28; 8(27): 1119-1127 Help Desk: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/helpdesk.aspx ISSN 1948-5182 (online) DOI: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i27.1119 © 2016 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. REVIEW Molecular pathological epidemiology in diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma Chun Gao Chun Gao, Department of Gastroenterology, China-Japan logy and epidemiology, and investigates the relationship Friendship Hospital, Ministry of Health, Beijing 100029, China between exogenous and endogenous exposure factors, tumor molecular signatures, and tumor initiation, progres- Author contributions: Gao C conceived the topic, performed sion, and response to treatment. Molecular epidemiology research, retrieved concerned literatures and wrote the paper. broadly encompasses MPE and conventional-type mole- cular epidemiology. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Supported by Beijing NOVA Programme of Beijing Municipal is the third most common cause of cancer-associated Science and Technology Commission, No. Z13110.7000413067. death worldwide and remains as a major public health Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest. challenge. Over the past few decades, a number of epidemiological studies have demonstrated that diabetes Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was mellitus (DM) is an established independent risk factor selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external for HCC. However, how DM affects the occurrence and